What Do You Do When the Elephants Arrive?

Keep Calm and Work Together!

By Gail C. Potgieter

9th August 2019

A farmer from a north-western communal area in Namibia is struggling to provide enough water and food for the livestock he has left after the devastating prolonged drought experienced in the country. To keep his flock watered he needs to buy diesel for the pump that fills the water trough; to prevent further livestock losses from the drought, he has bought some fodder for his animals. Once the animals are fed and watered he turns off the pump and stores the remaining fodder in a room attached to his hut. That night the elephants arrive.

These elephants, as stressed by the drought as the farmer, are desperate for water and always on the lookout for food. They arrive at the livestock trough to find that it is empty – the little ones cannot go much further without water, so the matriarch takes matters into her own trunk. She smells the water in the pipes that feed the trough and pulls one of these pipes right out of the ground, effortlessly. Fresh, clean water gushes out of the broken pipe, and the herd gathers around to drink to their hearts’ content. Later that evening, one of the herd smells something delicious emanating from a nearby hut – lucerne! He approaches the hut and finds it to be a makeshift structure of iron sheets and hardened earth – it is a simple matter for him to break down one of the walls and access bales of nutritious lucerne.

The farmer comes out of his hut the next day, having not slept a wink the entire night. He was angry when he first heard the pipes break, but that soon changed to terror when his house shook as the elephants broke the wall down. His wife and children were with him in the hut – the children nearly cried out, but they couldn’t risk drawing the elephant’s attention. Just the other day, an elephant killed their neighbour who was walking home at night. They were terrified.

Further to the north of this area, on a fenced commercial farm, another farmer is facing a different problem caused by the same great, grey beasts. An entire section of farm fence has been flattened: a sure sign that a breeding herd passed through here recently. Baby elephants cannot walk over fences, so the adults flatten large sections to let the babies through. As the farmer surveys the damage, he realises that this story is not over yet. These elephants will break out of this camp again soon, using a different route and destroying yet more fences. Besides the cost of repairing the fence, this farmer is deeply concerned about the animals he may lose before he can make sufficient repairs. He tries to calculate the financial cost of this incursion, but stops when it makes his head hurt.

The plight of these farmers has not gone unnoticed. Both the communal and the commercial farmers have lodged complaints with the Ministry of Environment and Tourism. The commercial farmers wrote letters to the local newspaper to publicise their problems, whilst the communal farmers complained vocally to the Ministry’s regional officers. Their requests were nonetheless the same: please take these elephants away.

This situation puts the Ministry in a very difficult position, as Kenneth /Uiseb, the Deputy Director of Wildlife, Monitoring and Research, explained to me in an interview. “The elephants that are causing these problems are from the west – the dry riverbeds in unfenced communal areas”, he points out. “If we took them to Etosha, they would just break out to return to the desert; if we took them west, they would just walk back again.” There are huge costs involved in moving elephants, which need to be darted and transported one at a time. These relocations also pose a risk to the elephants, especially if you are trying to move a breeding herd with young ones. So what should farmers do when elephants come knocking?

“The Ministry has adopted an integrated approach to dealing with human-elephant conflict”, /Uiseb explains. “Our overall aim is to reduce the costs of living with elephants to tolerable levels.” A key part of this approach is to find out where the elephants are going, and relay that information to the farmers in time for them to prevent major incidents.

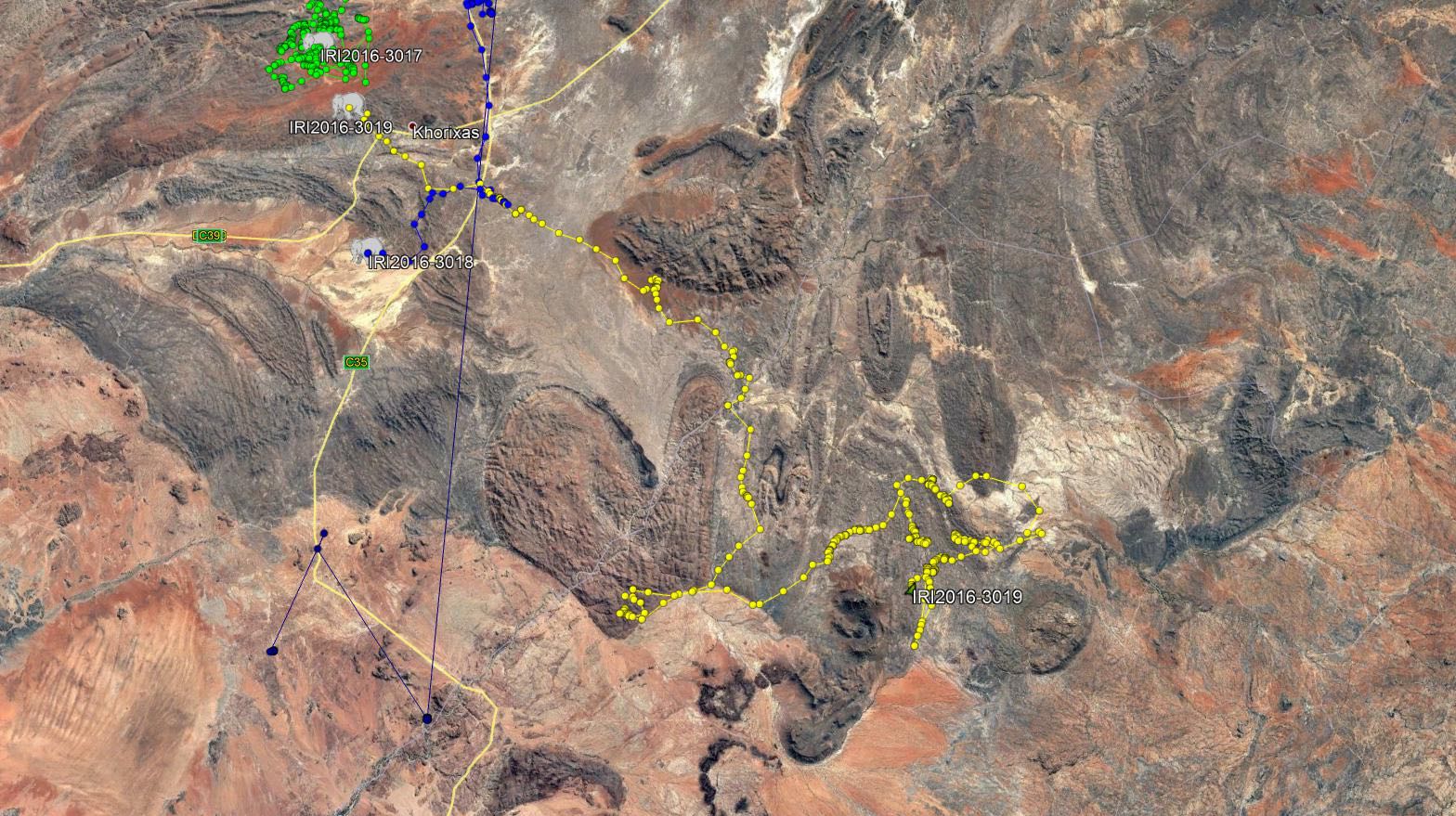

MET has been able to raise sufficient funds to collar 11 elephants from the Kamanjab commercial farming area in the north, right through to the Omatjete communal areas in the south. The Kamanjab Farmers Association, Horst Weimann (a local farmer and businessman), the German development agency GIZ and Namibian Breweries Limited (via the N/a’an ku sê Foundation) all contributed funds to MET’s collaring efforts. Elephant Human-Relations Aid, a field-based elephant conservation group, also assisted by tracking elephant groups that were earmarked for collaring by MET.

Knowing where the elephants are has helped the commercial farmers in the Kamanjab farming area substantially, and this project has greatly increased their tolerance despite the continuing fence breakages. MET is currently setting up a system to inform the southern communal farmers about the elephant’s whereabouts through their regional offices and the local radio stations. To address the fodder issue, MET has built an elephant-proof storeroom in the area. It is hoped that farmers will take steps to protect themselves and their livestock fodder when they are alerted to the presence of elephants via the radio.

The community in the south needs more than just information, however, as they cannot afford to pump enough water for elephants and their livestock, nor can they keep fixing broken pipes and reservoirs. To address this need, MET is working to replace the diesel pumps with solar pumps, build protective walls around the water installations, and build alternative elephant watering points some distance away from human settlements. Furthermore, they are looking to increase tourism in this area by building a lodge and working with local tour operators to create a safari route. By improving benefits and reducing the costs of living with elephants, MET hopes to help this community to coexist with these giants.

These interventions provide support to the country’s well-known conservancy programme. The commercial farming area is located within the Loxodonta Africana freehold (commercial) conservancy, which is aptly named after the African elephant. In the south, communities have established the Ohungu and Otjimboyo communal conservancies, and another community that lives with elephants is considering establishing their own conservancy soon. These entities make it easier for tourism operators to establish working relationships with the communities and provide a means for developing new community projects.

“Besides trying to reduce conflict, we are also interested in understanding the elephants’ movements from a research perspective”, /Uiseb explains. “It seems that the drought is driving these elephants further east, and we want to know more about how these groups link with others that have remained in the west”. They are especially interested in finding out how the bulls move through this landscape, and whether or not they provide genetic links between different breeding herds in the region. Kenneth /Uiseb gives me an example: “One of our collared bulls walked 50 kilometres from the Ugab River to the Huab River and now lives in the Fransfontein area between Khorixas and Kamanjab.”

Besides shedding light on the ecology of these free-ranging elephants, the data will be used to make more informed policies and decisions. Climate change predictions indicated that Namibia’s climate will get drier still, and droughts such as the one we are currently experiencing will get longer and more severe over time. It seems that the drought is the primary cause for elephants moving east, but it will be interesting to see how or if their range changes according to future rainfall patterns.

In the north-eastern parts of the country similar changes are taking place as elephants move away from the dry Kalahari towards commercial farmlands around Grootfontein. The future of free-ranging elephants in Namibia therefore lies in the hands of livestock farmers. MET’s integrated approach holds some promise for increasing farmer tolerance for these charismatic animals. Living with elephants is difficult, but Namibian farmers are showing that it can be done.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.