Using Namibia's Wildlife to Drive a Green Economy

Namibian Chamber of Environment

15th November 2019

Since the 1960s, Namibia has enacted policies that grant rights and responsibilities to manage and use wild animals to the people living in rural areas. This rights-based policy has extended from freehold farms to communal areas since independence. Namibia’s strategy has borne both economic and conservation fruits over the last few decades, and the future of wildlife-based land use is brighter still. As we look into the future, we need to consider local and global environmental and economic trends that Namibia can use to capitalise on its natural resources in order to promote sustainable development.

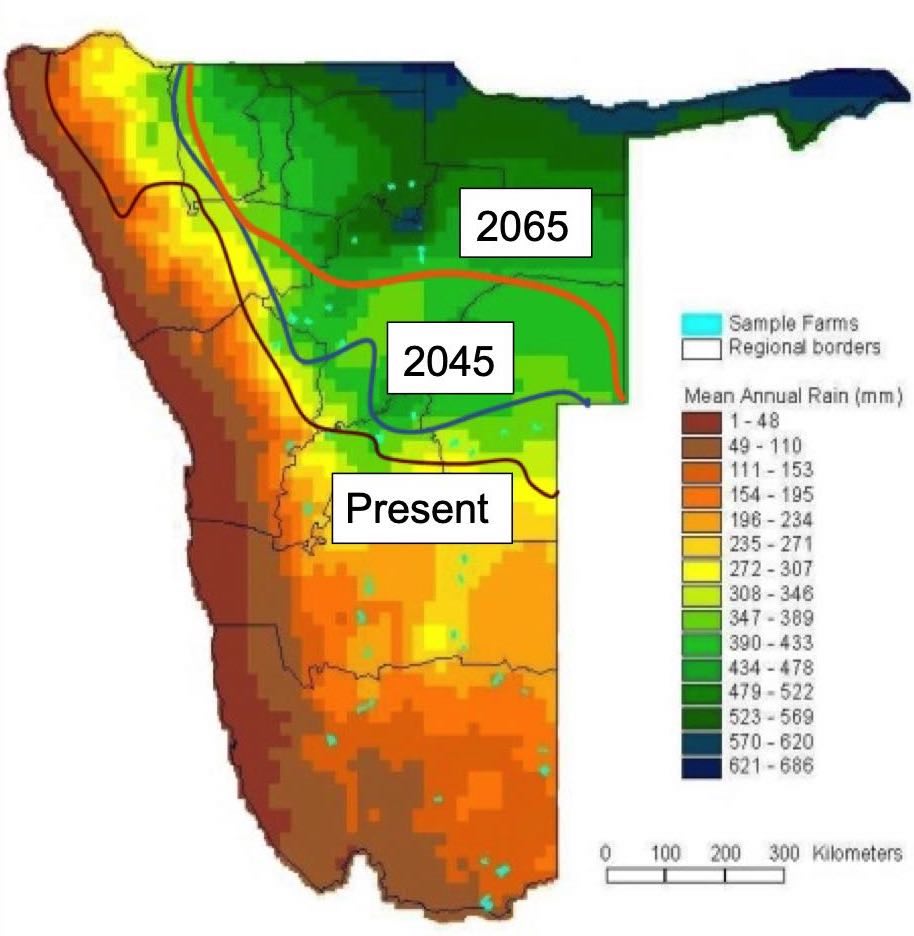

The key environmental trend to consider is climate change, which is making Namibia even hotter and drier than it was 10 years ago. Climate change predictions reveal that livestock farming will become increasingly difficult: prime cattle farming areas today will become marginal for cattle within the next 25-45 years; similarly, many areas in southern Namibia that are today used for small stock farming will become too dry for any form of livestock (see map). This trend alone indicates the need for the agriculture sector to move towards using indigenous wildlife that is better suited to Namibia’s arid climate than domestic livestock.

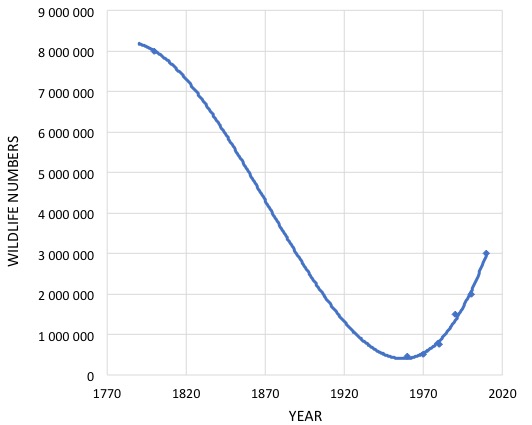

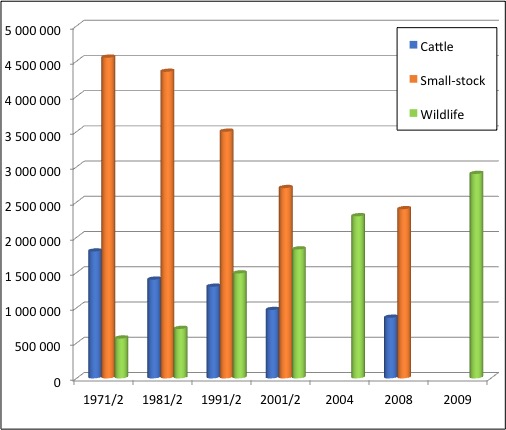

Current trends within the agriculture sector reveal that farmers are already switching to wildlife use, due to both economic and environmental realities. Economically, wildlife has a competitive advantage over livestock in areas of low rainfall (i.e. about < 1,000 mm per year), which describes all of Namibia and over 65% of southern Africa. The wildlife sector is also more economically diverse than the livestock sector, as game farmers can move beyond meat production by offering hunting and tourism operations and the sale of live animals that add additional value to their wildlife. These service-based industries have a much greater potential for growth than agricultural production-based industries. These market and environmental forces have led to the steady growth of commercial game farming in Namibia, whilst cattle and small stock farming continues to decline. Similar increases in wildlife have been documented on communal land in conservancies.

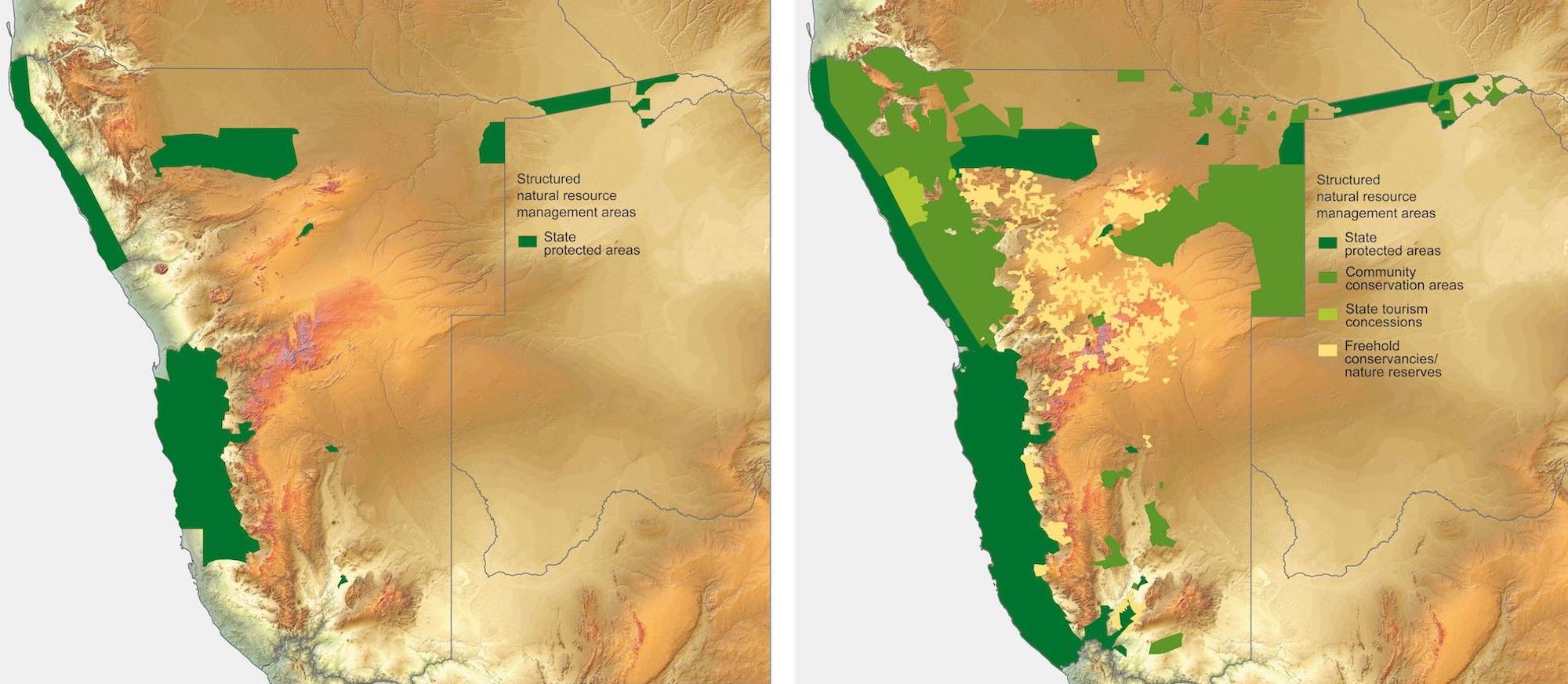

The extension of wildlife ownership rights from freehold to communal land in 1996 was a first, vital step towards including more Namibians in the wildlife-based industry. The communal conservancies that established as a result of this policy generated over N$132 million for conservancies during 2017, and this figure continues to grow year on year. Like the freehold game farms, these conservancies earn most of their income through tourism and hunting, and meat production makes an important contribution to rural food security.

Going beyond pure economic gains, Namibia’s policy of devolving wildlife ownership rights to farmers has produced conservation dividends. While the extent of land and number of wildlife conserved in National Parks has grown slowly over time, the land area and wildlife populations conserved on freehold and communal lands has increased dramatically. Today, National Parks host only 6% of Namibia’s wildlife populations by number (more by biomass), whilst 12% occurs on communal land and 82% occurs on private land.

Considering the broader landscape, communal conservancies now provide a connection between Etosha and Skeleton Coast National Parks and are a key reason for the expansion of both the lion and elephant populations in this region. Land under wildlife and biodiversity management, both communal and freehold, are neighbours to over 80% of national park borders within Namibia. Conflicts on park borders are thus hugely reduced as both parties have similar management objectives.

Namibia can be proud of its growing wildlife industry and subsequent conservation achievements, but there is much room for further economic and conservation growth. First, the economic returns per hectare of wildlife on communal conservancies remain small compared to that on freehold land. There remains scope for improving this situation by introducing more investment and efficient business practices and capturing larger proportions of the income generated through ecotourism and hunting for the conservancies. These improved economic gains must be accompanied by more advanced systems of governance to ensure that they are translated into tangible benefits for conservancy members. There are a number of policy constraints that currently dampen investment on communal land, to the detriment of economic growth, poverty reduction, employment creation and conservation. These constraints have been discussed for many years, yet to date no tangible resolution has been achieved.

Second, the wildlife sector on both freehold and communal land will benefit by removing barriers to including high-value wildlife species and wildlife products in the wildlife economy chain. These species include black and white rhino, elephant and buffalo. Rhino horn is more valuable than gold, and is a renewable resource – dehorned rhinos can grow their horns back within a couple of years. Currently, farmers may view rhinos as a liability due to the resources required to protect them from poachers; legalising trade in rhino horn could incentivise more farmers, both communal and freehold, to manage rhino on their land as a valuable asset. Similarly, and international trade in elephant ivory from natural mortality and population management would incentivise farmers to include this difficult-to-manage species on their land. Legalisation of rhino horn and elephant ivory would require international cooperation and strict monitoring protocols, but this can be done.

Unlike rhino, conserving buffalo on land outside National Parks would require relatively simple changes to national policies. Disease-free buffalo are extremely valuable as a tourism and hunting species (including live sales), and present no threat to cattle. Yet current outdated laws favour the smaller, shrinking cattle farming industry over the larger, growing wildlife farming industry by preventing game farmers from stocking buffalo. If these legislative barriers were removed, the wildlife industry would grow stronger still, with clear benefits to the national economy and Namibian citizens.

Third, and finally, the wildlife industry can generate greater financial returns per hectare, contribute more meaningfully to biodiversity conservation goals and become more sustainable in the long-term by operating at a landscape level. This means that we move beyond farm-based boundaries to managing wildlife collaboratively over larger areas.

Namibia can learn valuable lessons in this regard from neighbouring South Africa of what not to do, where the wildlife industry has become increasingly intensive – game animals are bred in ever-smaller camps, and have consequently lost much of their genetic variability. Also, breeding species with unnatural colours and caged lion hunting has severely damaged the conservation reputation of South Africa; in the medium-to-long-term this will result in negative economic performance. These intensive systems are unsustainable, as wildlife lose their natural adaptations to the environment, and require continuous management.

Despite the many amazing adaptations our wildlife have for hot, arid conditions such as brain blood-cooling mechanisms, concentration of excreted waste products to save water and behavioural responses to minimise heating, the overriding priority for survival is mobility – the ability of animals to cover large areas to find patchy food, moisture and trace minerals in response to highly variable climatic conditions. Fencing animals in farm-size camps removes this vital adaptation.

Namibia has the opportunity to open up larger, continuous landscapes through the conservancy system, which require less management and are more attractive for tourism and hunters. They are also better for investment and marketing. In this way, the country could restore ecosystems to close to their former state whilst simultaneously stimulating economic growth and job creation, further bolstering its reputation as a forerunner in wildlife conservation and sustainable development.

Namibia has already made great strides towards developing a thriving wildlife-based economy, but that is no reason to rest on our laurels. Globally, wilderness areas are shrinking, ecosystems are being destroyed and fragmented, and climate change threatens rural livelihoods. Although not immune to these dangers, Namibia is now ideally placed to capitalise on these global trends by further expanding its ‘green economy’ to include high-value species and wildlife products, and focus on larger, intact ecosystems.

Our communal and freehold conservancies, national and privately managed parks are collectively ideally placed to realise this goal, and it is therefore imperative that we continue to invest in these structures. If Namibia’s wildlife and wilderness areas are fully recognised as its comparative competitive advantage on the global economic stage, the future will be green indeed.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this article, then you might also like:

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.orgThe Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.org

Dr. Chris Brown, ecologist, and environmental scientist, has over thirty-five years' practical experience in environmental management and administration, strategic planning and development, project and programme design and coordination. Previously he was Head of the Namibia Directorate of Environmental Affairs (DEA) in the Ministry of Environment and Tourism and played a key role in drafting the environmental clauses in the Namibian Constitution. He was the Executive Director of the Namibia Nature Foundation for 12 years. He serves on several boards including that of Namibia's Sustainable Development Advisory Council, and is CEO of the Namibian Chamber of Environment.

Dr. Chris Brown, ecologist, and environmental scientist, has over thirty-five years' practical experience in environmental management and administration, strategic planning and development, project and programme design and coordination. Previously he was Head of the Namibia Directorate of Environmental Affairs (DEA) in the Ministry of Environment and Tourism and played a key role in drafting the environmental clauses in the Namibian Constitution. He was the Executive Director of the Namibia Nature Foundation for 12 years. He serves on several boards including that of Namibia's Sustainable Development Advisory Council, and is CEO of the Namibian Chamber of Environment.

Share:

Subscribe

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.