Introducing Community Conservation Namibia.com

Namibian Chamber of Environment

20th February 2020

I recently explored a brand new website called Community Conservation Namibia, which attractively presents the current state of communal conservancies in the country. A combination of hard data, personal stories, and clear explanations of each facet of the programme, this website is a gold mine for anyone who is interested in the role rural communities play in conservation. I will take you on a tour of the new website’s highlights here, yet you really need to visit the site yourself to get the full benefit of this excellent resource.

The Namibian conservancy programme has always been known among conservation professionals as both a success story and a valuable source of information about how community conservation works. Considering the current scope of the programme – with 86 conservancies registered to date – collating and presenting this information is no mean feat. Previous reports on the state of conservancies were only available in hardcopy or as PDF downloads; this new website makes this information far more accessible.

These efforts further reveal the transparency in the programme. The data comes straight from the men and women working for the conservancies through to head offices in Windhoek, where the information is collated into a suitable reporting format. The challenges of human-wildlife conflict, conservancy governance, community benefits and wildlife crime are all tackled head-on by discussing each issue based on current data and trends.

Trends in game numbers from 2001 to 2018 provide insights into population health of a wide variety of species – from antelope to elephants and large carnivores. While the long-term trend is positive, the serious, multi-year drought has contributed to recent population declines. Conservancies in the north-western Kunene Region were especially hard hit, where people, livestock and wild herbivores are all struggling to survive. As the drought approached, the conservancies and their advisors decided to harvest large numbers of wild antelope to prevent mass die-offs and reduce competition between wildlife and livestock during these desperate times. On the positive side, wildlife in this desert region will return and flourish once again with the rains – this is ultimately part of a natural cycle, although climate change may exacerbate this problem in future.

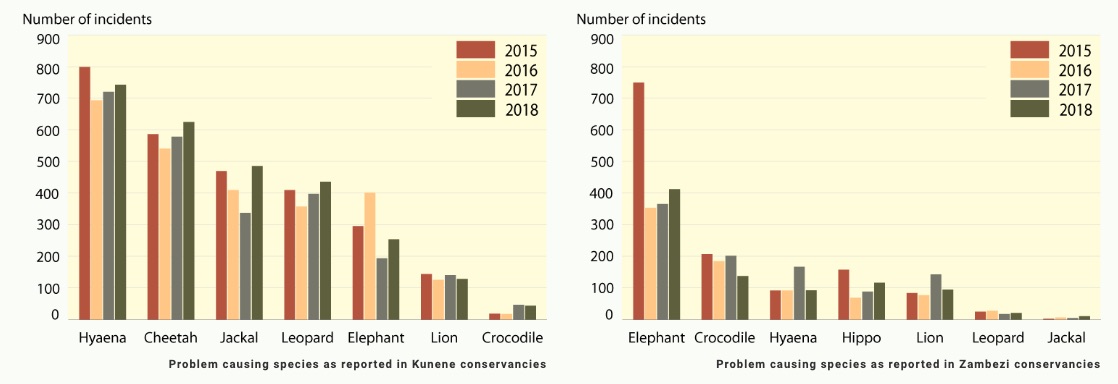

Perhaps the only species that are coming out on top in the Kunene are the carnivores, with spotted hyaena and black-backed jackal populations on the rise for the last four years. The lion population spiked four years ago, but they are the most heavily impacted by human-wildlife conflict and people are less willing to tolerate losses from lions when they are already suffering from drought. Conservancies are not National Parks and therefore have different objectives, focusing on supporting people and their livelihoods through the wise use of their natural resources. Consequently, while lions and other dangerous species are fully protected in the National Parks, in conservancies the ecological needs of these species must be balanced with the needs of local people.

In contrast to the Kunene, the conservancies in the north-eastern Zambezi Region report a general increase in herbivore numbers (particularly buffalo, impala and zebra) over the last decade, but it seems that some of the carnivores may be in trouble. Spotted hyaenas, in particular, are seen less often in the last few years than they were in the early 2000’s and jackals appear to have followed suit. It is difficult to say what is driving these trends, as leopard, lion and wild dog populations have fluctuated but not declined over the same time period. Elephant poaching remains a concern in this region and fewer elephants have been seen during conservancy game counts. An aerial survey was completed this year to get a better picture of elephant numbers, the results of which will become available next year.

Stepping back from the details of how the programme is managed, a whole section of the new website site looks at how communal conservancies make a difference on a larger scale. Nationally, they contribute significantly to the rural economy and to conservation by maintaining wildlife linkages between the National Parks. Conservancies in the north-east are also an important part of an international conservation landscape – the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area that covers four countries besides Namibia. The Namibian programme has an even greater impact than the sum of its conservancies, however, as conservationists come from around the world to learn how community conservation works so they can try it in their own countries.

My favourite section of the website covers the history of the community conservation programme in Namibia. It traces the programme from its earliest roots in the 80’s before the country achieved independence and abolished apartheid in 1990. The very first people who became involved were respected members of their communities who were elected as community game guards to monitor the status of wildlife in their areas.

The traditional leaders who endorsed the concept understood that if poaching continued without any form of management, their children and grandchildren would grow up without wildlife. In some cases, the newly appointed game guards were poachers themselves who were now assigned to look after the wildlife on behalf of their communities. They too realised that their former hunting practices were unsustainable and that change was needed if they wanted to use wildlife in future.

All of this critical groundwork led to the new government of Namibia passing legislation in 1996 that allowed communities to establish conservancies and thus gain conditional rights to use their wildlife. The first four conservancies were gazetted two years later and that number has grown ever since, as more rural communities realise the opportunity to benefit from their wildlife.

As the programme expanded, government and civil society increased their support for conservancies with funding from key international donors. Any given conservancy’s success nonetheless hinges on the people who live there – if the people in conservancies are no longer willing to live with wildlife, the programme would collapse. It is therefore critical to ensure that the programme maintains its momentum among conservancy members by drawing in the next generation of community leaders and further expanding the economic potential of communal conservancies.

Most conservancies rely on a mix of income sources that include photographic tourism, hunting (for meat and trophies) and harvesting plants for medicinal and other uses. The data reveal that new conservancies rely entirely on hunting until their infrastructure is sufficiently developed to accommodate photographic tourists, with most established conservancies using both types of tourism to generate income. While these sectors currently provide employment and direct income for the conservancies, there is still scope for growth. Local entrepreneurs require more support to take advantage of the opportunities created by conservancies drawing tourists and opening up new markets.

Twenty-four years after the ground breaking conservancy legislation, the programme is still going strong. There is always more work to do, however, including finding innovative ways to reduce human-wildlife conflict in established conservancies, bringing new conservancies up to speed, and increasing the tangible benefits each household receives by being conservancy members. You can watch this space by visiting communityconservationnamibia.com for regular updates.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.orgThe Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.org

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.