Understanding and Conserving the Namibia-Botswana Zebra Migration

24th August 2020

This article was written with inputs from Debbie Gibson and Colin Craig (DG Ecological Consulting), Robin Naidoo (WWF-Namibia), Jo Tagg (Rooikat Trust), Helge Denker, and Chris Brown (Namibian Chamber of Environment). MEFT granted permission to use the aerial survey maps.

It has been eight years since researchers in Namibia and Botswana discovered the record-breaking zebra migration between Namibia’s Zambezi Region and Botswana’s Nxai Pan and Makgadikgadi Pan. While the discovery was significant, it raised many research questions that have yet to be answered and highlighted the need to conserve this migratory population.

As a start, we need to continue monitoring the zebra population on both ends of the migration, to check that they are not declining and to find out if the migration start and end points change from year to year. This basic monitoring information can be obtained from the sky. Aerial surveys are a fairly accurate means of counting herbivores like elephant, antelope, and indeed zebras.

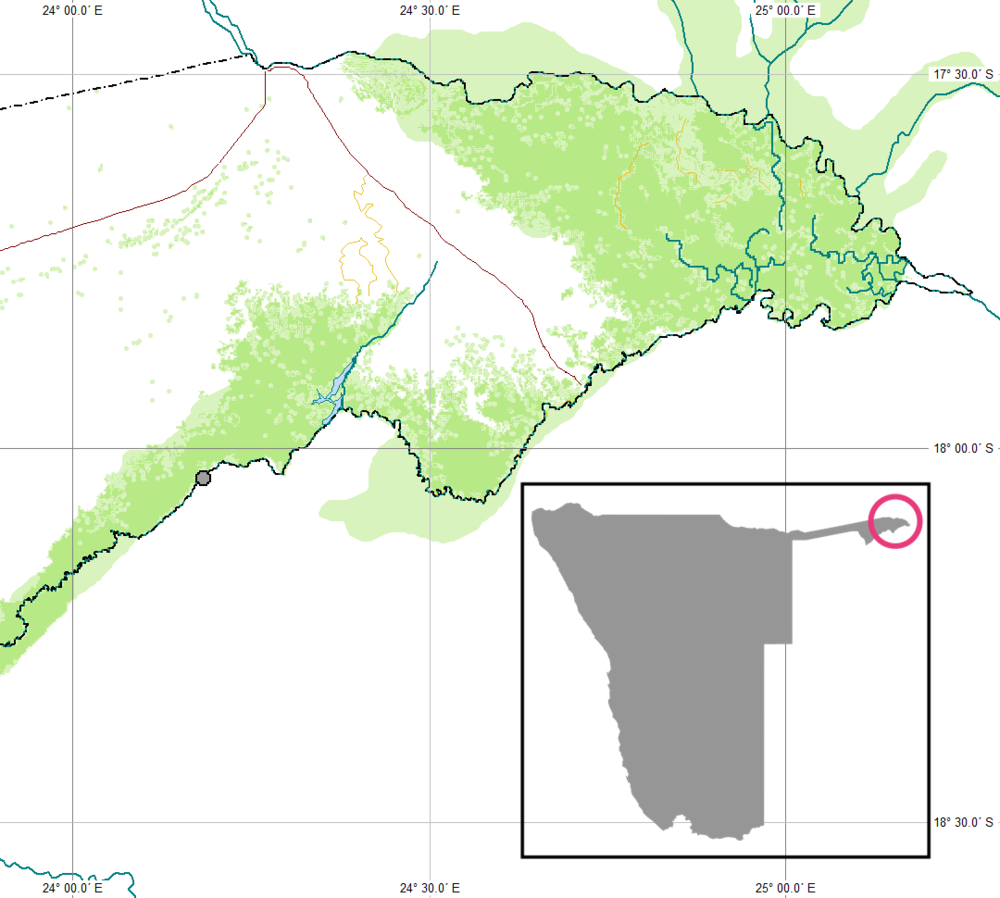

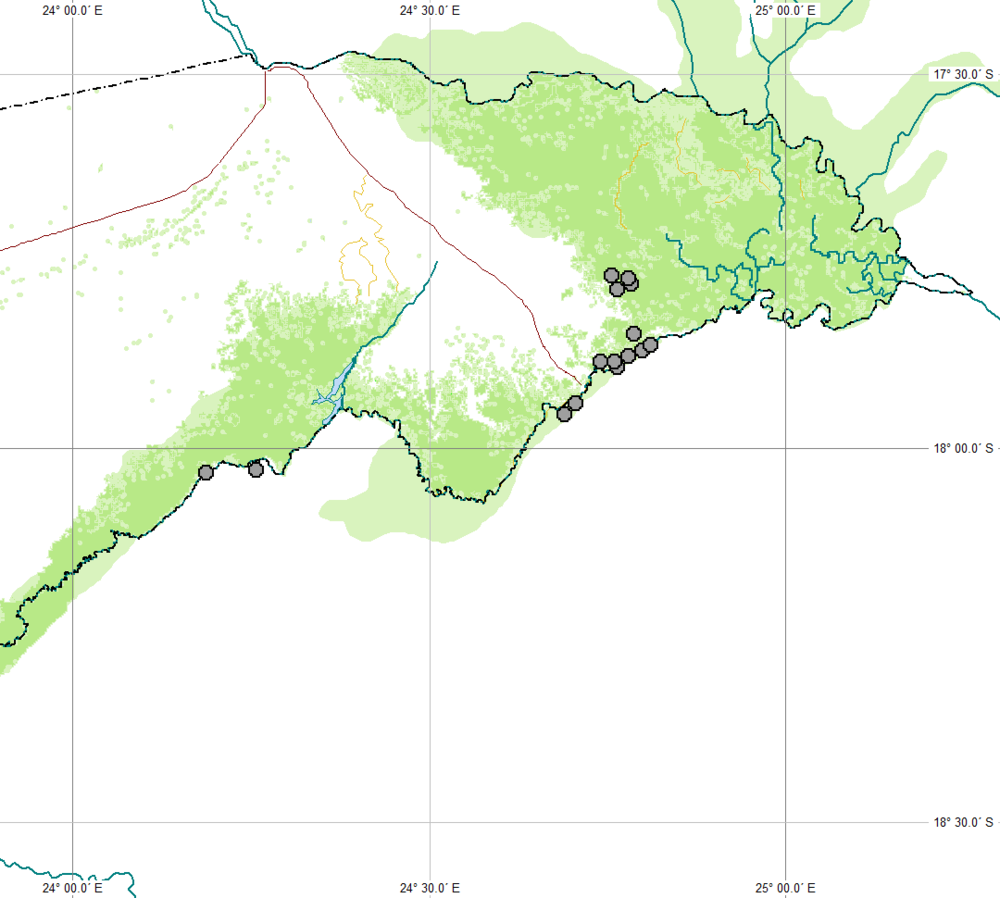

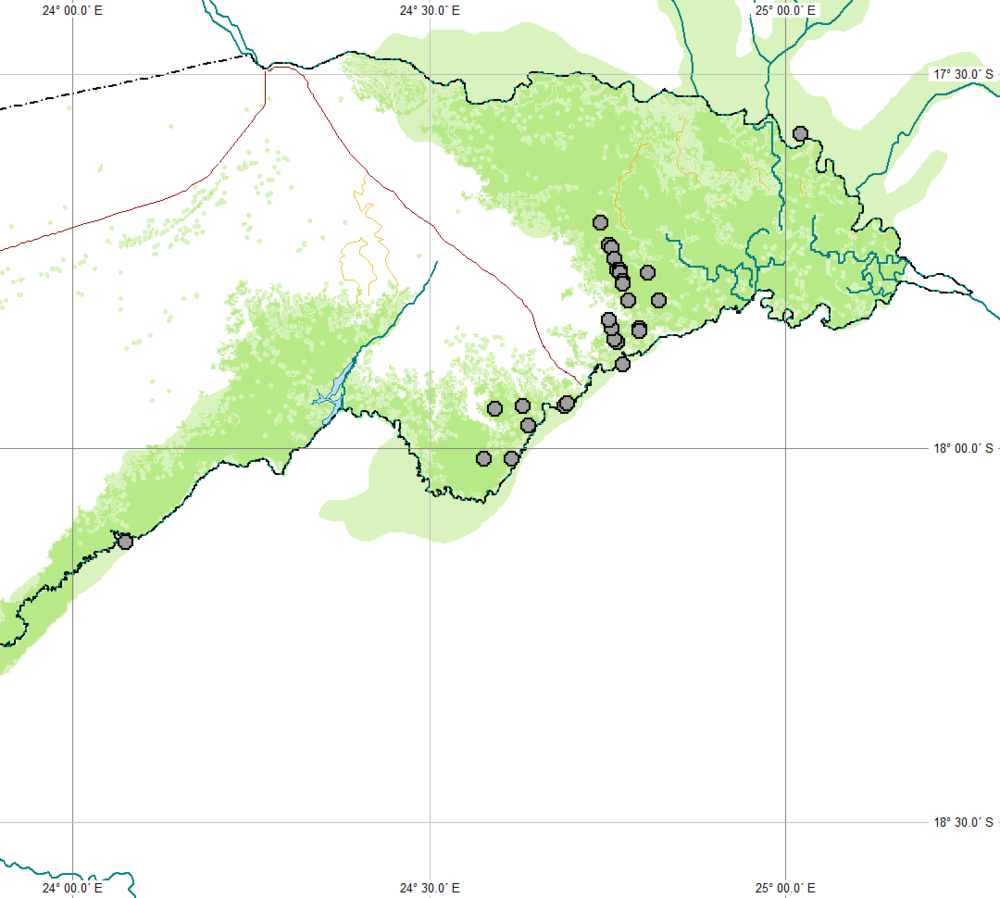

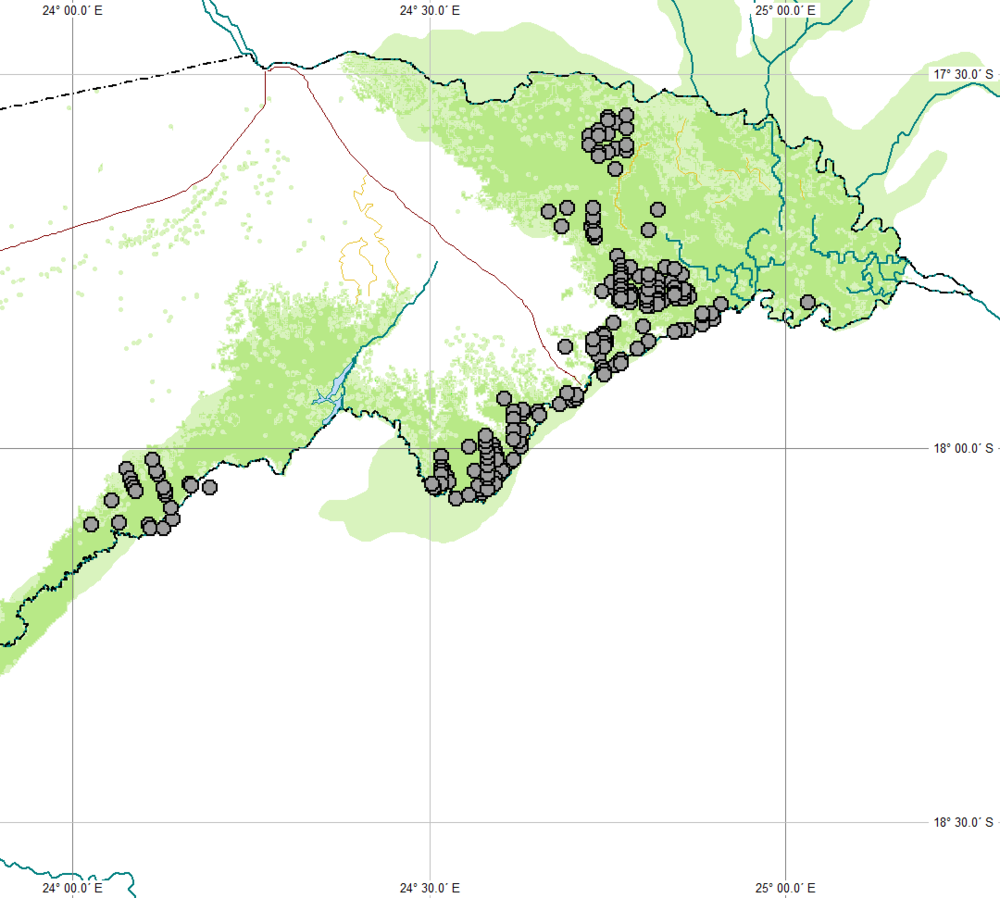

The Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) regularly commissions an independent ecological consulting company to conduct aerial surveys in the Zambezi Region, which supplement on-going monitoring efforts by communal conservancies on the ground. In 2019, the Rooikat Trust provided extra funding for the survey team to increase their survey intensity (i.e. number of times they fly over a given area) for the far eastern end of the Zambezi Region where the migratory zebra population occurs.

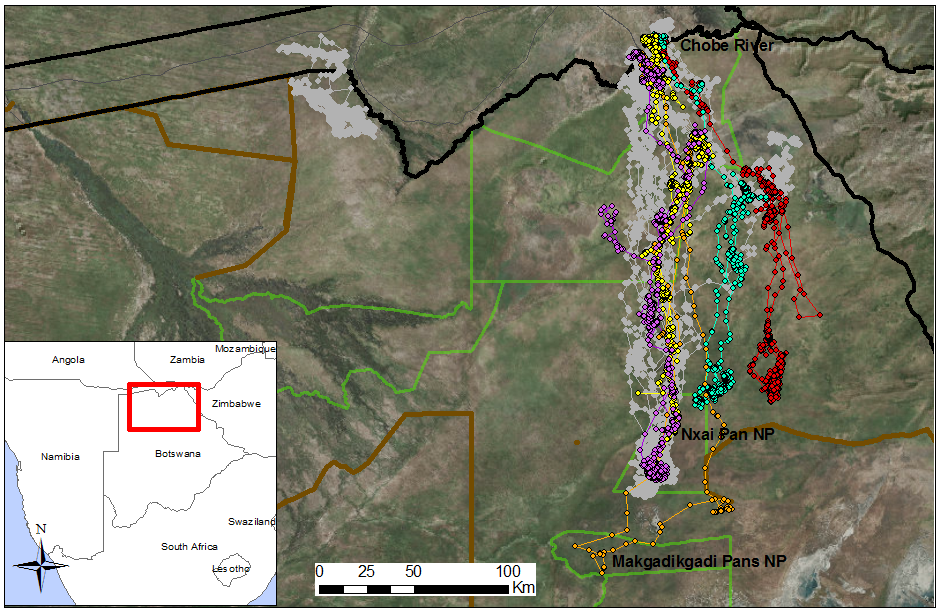

Their results are fascinating, and highlight many questions about these zebra that we still need to answer. From almost no zebra observed during the 2013 aerial survey, the estimated zebra population from the 2019 survey is 8,859 (range 4,643-13,075). The zebra sighting locations in 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2019 surveys further tell a compelling story of range expansion – the zebra seem to be pushing ever further north, almost reaching the Zambezi River during 2019. Data from the game counts done by foot every year in these conservancies confirm that the zebra populations have increased steadily since 2007.

The questions arising from these observations concern both Namibia and Botswana, which is why transboundary research and conservation is so important. For example, do all of the zebra found grazing in the eastern floodplains of Namibia in 2019 originate from Nxai Pan, or did some of them do a quick border-hop from places like Chobe National Park? Where do the zebra that travel the furthest north go? Do all of the zebra that live in Nxai Pan travel north to Namibia, or do they branch off to other destinations, leaving relatively few to make the amazing 250 km journey?

Researchers from Namibia (WWF) and Botswana (Elephants Without Borders – EWB) have collared a number of the migrating zebras with satellite tracking devices. Their data reveal that not all zebra go to the same place – one individual even bypassed Nxai Pan and walked all the way to the Makgadikgadi Pan! More recent EWB research shows that while these zebra in the east travel long distances, those living further west in the Mudumu and Nkasa Rupara National Parks in Namibia make a shorter trip into the eastern edge of the Okavango Delta in Botswana.

Figuring out what is happening with the zebra today also requires a long-term perspective and understanding of the history of land management and conservation in both countries. We know that livestock fencing in Botswana that was erected to reduce wildlife-to-livestock disease transmission in the 1960’s caused severe disruption of animal migrations at that time, which was particularly deadly for wildebeest. So the animals remaining in Botswana have either stopped migrating (risking death during the dry season) or managed to find other migratory routes to maintain their body condition throughout the year. On the Namibian side, we know that there was widespread, severe poaching in the Caprivi Strip (now Zambezi Region) in the late 1960’s through to the late 1980’s that likely resulted in fewer migratory animals surviving the journey.

Today, while many disease control fences are still present in Botswana, the remaining wildlife has adapted to the new conditions. Encouragingly, the removal of one of these fences resulted in zebras resuming their migration between Makgadikgadi Pan and the Okavango Delta. Meanwhile, Namibian conservancies have greatly reduced poaching in the Zambezi Region, so wildlife can use this area alongside cattle and other livestock. This begs another question: are the zebra coming into Namibia now re-establishing an ancient migratory route that existed prior to heavy poaching in the Zambezi, or is this a new route created because others have been cut off by fencing?

Further, is there a genetic difference between the different zebra populations that migrate to and from different areas? Genetic differences (or similarities) could shed light on how old this migration is and how these zebra relate to others that migrate elsewhere. The oral history of the people who live in the area and written accounts from early visitors could also shed light on the age of this migration. Some of the older people living in this area recall that zebra were common in this part of the Zambezi Region before the period of severe poaching. What we don’t know is whether some or all of them migrated as far as Nxai Pan in those days.

Ecological conditions change over time; long-term monitoring over a number of years is thus required to investigate how these factors change the migration. One of the key features of the landscape is the Chobe River – some years it dries up almost entirely, while in others it remains in full flow. It seems that zebra are willing to swim across the river even when it is relatively deep, such that some may fall prey to crocodiles and foals may even drown in the attempt. Getting to the floodplains in Namibia is clearly worth risking their lives – what drives them?

While we don’t yet know the history of the migration, or the current ecological drivers for it, we nonetheless recognise the need to conserve this migration as one of the few left in the world. Namibia and Botswana are both part of the Kavango-Zambezi (KAZA) Trans-frontier Conservation Area and researchers in both countries discovered this migration and are interested in studying it further, so a strong basis for collaboration already exists.

Besides answering the above questions, one would need to find out what human-caused risks these zebra encounter during the migration and if anything could be done to mitigate those risks. If the zebra that make it to Namibia are just a portion of those setting out from Nxai Pan, figuring out where the others go and what risks they face would need to be included in a conservation plan for the population. Historical human actions and their current consequences have thrown down a gauntlet for zebras trying to find suitable pasture throughout the year. Protecting them on their journey is the least we can do.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this article, then you might also like:

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

Gail Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

Share:

Subscribe

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.