Spotty cats, solid data

Namibia's first national cheetah survey

9th March 2021

Namibia is home to the largest population of cheetahs left on earth (which it shares with neighbouring Botswana), and is therefore a critical stronghold for this threatened big cat species. Surprisingly, an intensive nation-wide effort to estimate their numbers using a consistent approach has not been attempted – until now. A team of researchers who have analysed the movements of 19 GPS-collared cheetahs, sorted thousands of photographs from 15,000 nights of camera trapping, spent over 400 nights camping, and driven over 112,000 km (thus far!) aim to fill this knowledge gap.

The Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) is collaborating with a team of cheetah experts from the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) to do the first Namibian cheetah survey of its kind. This effort began with intensive studies in five different parts of Namibia during 2015-2017 and was extended to include two (possibly three, funding dependent) more sites in early 2020, to be concluded in early 2022.

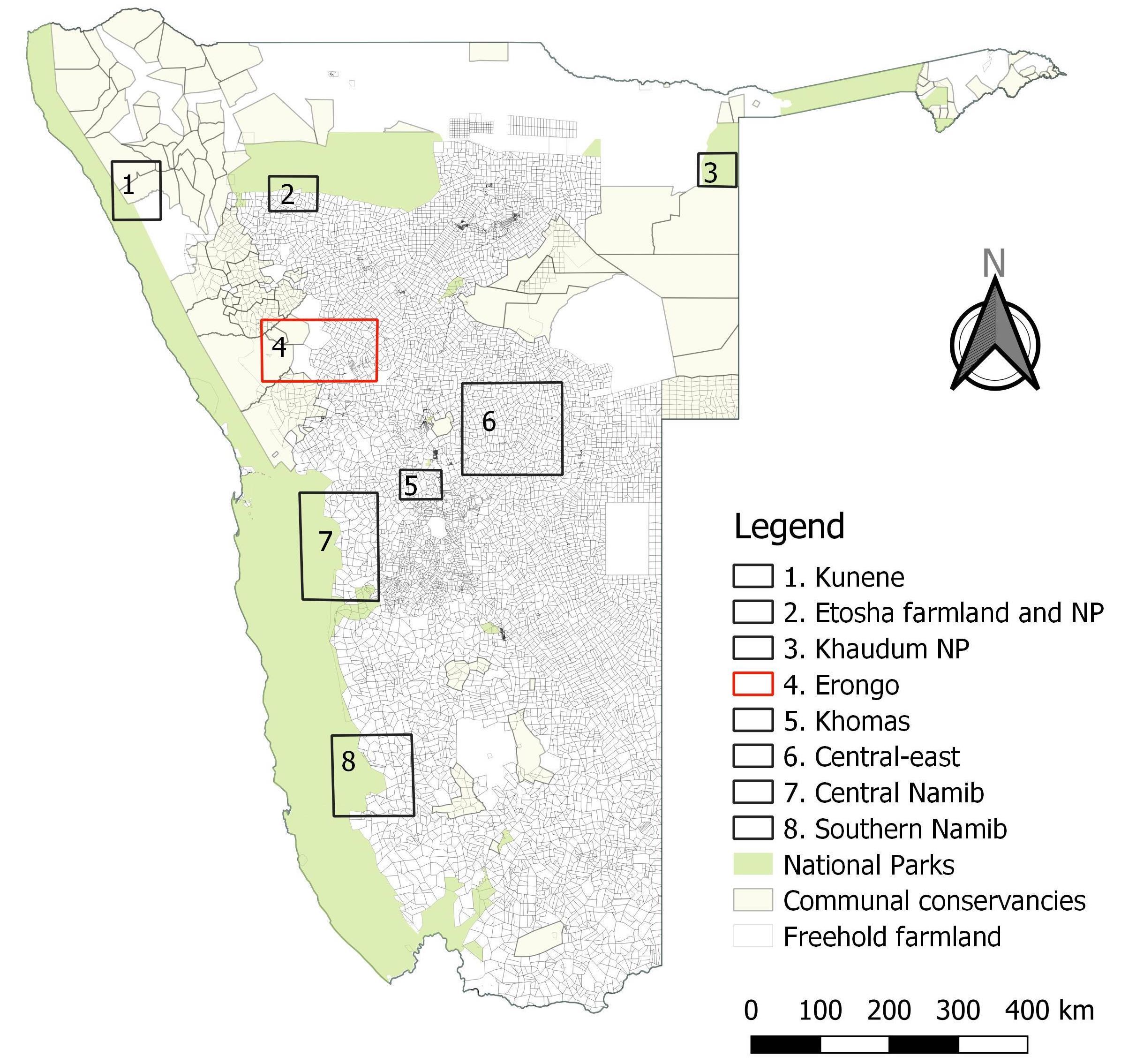

The study sites are scattered over diverse parts of known cheetah range in the country, covering different habitat types and climates, land uses (e.g. communal and freehold farmlands), and levels of protection (some are within National Parks, others outside). Cheetah densities obtained from these representative sites can therefore be used to estimate the numbers of cheetahs in similar areas (the national leopard survey was based on similar principles).

While previous cheetah estimates (globally and for southern Africa only) were based on results from a variety of studies using different methods and opportunistic sightings, this one takes a systematic approach that is repeated in each survey area using a combination of GPS satellite collars and camera traps. Although camera traps are used to study many different carnivore species, the IZW researchers have applied their knowledge of the cheetah’s unique movement patterns gained from an 18-year study to greatly increase the accuracy of their final population estimates.

The researchers know that cheetahs use special marking sites (e.g. large trees, termite mounds or prominent rocky outcrops) to keep track of each other’s movements and status – like humans use Facebook or Twitter. Territorial males use this messaging system most often, as up to 40 marking sites are located in the core area of their territory. Other males that are still looking for territories (dubbed floaters

) will visit these sites to check out the territorial males’ status (if these males die or get too old, the floaters will take over), meanwhile females will use the sites to advertise when they are ready to mate. In this sense, the core areas of male cheetah territories function as communication hubs for the regional cheetah population with individual floaters and females visiting from up to 50km away. If you want to know how many cheetahs live in a given region, your best bet is to place your camera traps at the cheetahs’ favourite marking sites within these communication hubs.

Observant humans can find these cheetah play trees

(as the farmers know them) by looking for cheetah scat on or around trees, termite mounds or rocky outcrops. The most reliable way to find as many as possible, however, is to follow a male cheetah. The IZW team achieves this by fitting three males in each study area with GPS satellite collars and recording their movements. With this information, marking sites can be easily detected and then visited on the ground to find out which them are the most popular in the cheetah community (many different scats are the equivalent of many likes on Facebook).

Once the 10 most popular sites within each of the three communication hubs are identified, two camera traps are placed at each site to try and get good photos of both sides of every visiting cheetah. Each cheetah can be identified by its unique coat pattern, which allows the researchers to see how many cheetahs come to the site and how often each individual comes back during the two-month survey period.

Finally, after many hours of sorting photos and a bit of data analysis, the researchers can produce a fairly accurate cheetah population estimate for each study site. These estimates are then used to calculate how many cheetahs there are likely to be in similar areas elsewhere in Namibia using statistical modelling. For example, the estimate from the Kunene study area would be used for other communal lands in the north-west, while the estimate from the central-eastern study area would be used for freehold lands in the east, and so on for each study site and corresponding region. The results of this survey and subsequent analyses will thus produce the most accurate national estimate to date.

The researchers are not alone in their endeavours, nor are they keeping their expertise and knowledge to themselves. Five students from the Namibia University of Science and Technology were employed as interns and trained to do both field and computer work, thus gaining valuable experience as conservation researchers. MEFT wardens and rangers also receive valuable training in cheetah ecology and information that they can use for management purposes, particularly in the National Parks. Importantly, the IZW team gives regular presentations to the farmers and other stakeholders in each study area to make sure that everyone is kept up to date and informed.

Knowing how many cheetahs there are in Namibia will be useful to guide MEFT policies regarding their protection and create awareness among Namibians about their status. As a globally important cheetah population, an accurate estimate for Namibia will be a significant contribution to re-evaluating the status of this species throughout Africa (some have suggested up-listing from Vulnerable to Endangered). The results of the national cheetah survey are therefore eagerly anticipated by everyone who is concerned about the future of the world’s fastest land mammal.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this article, then you might also like:

The Leibniz-IZW conducts evolutionary wildlife research to guide conservation actions. Our vision comprises two goals: (1) understanding adaptability of wildlife in the context of global change, and (2) designing appropriate conservation interventions to improve this adaptability. Our knowledge about the complex interplay between wildlife and their environment is still limited and it is therefore difficult to forecast the response of species to changes in their environment. Such forecasts are urgently needed in order to design appropriate conservation interventions and prioritise resource use for conservation.

www.izw-berlin.de/en/The Leibniz-IZW conducts evolutionary wildlife research to guide conservation actions. Our vision comprises two goals: (1) understanding adaptability of wildlife in the context of global change, and (2) designing appropriate conservation interventions to improve this adaptability. Our knowledge about the complex interplay between wildlife and their environment is still limited and it is therefore difficult to forecast the response of species to changes in their environment. Such forecasts are urgently needed in order to design appropriate conservation interventions and prioritise resource use for conservation.

www.izw-berlin.de/en/Project supporters: The Namibian cheetah survey is supported financially and logistically by the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism, the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research of Berlin, the Messerli Foundation, WWF Germany and the Namibian Chamber of Environment. If you would like to donate to the survey to allow the researchers to include one more study site and do the final statistical modelling, email Dr Joerg Melzheimer at:

melzheimer[at]izw-berlin.de