Are Namibian Fairy Circles Euphorbia Tombstones?

25th February 2021

I would like to thank Prof. Marion Meyer for checking the text and providing photographs and the map.

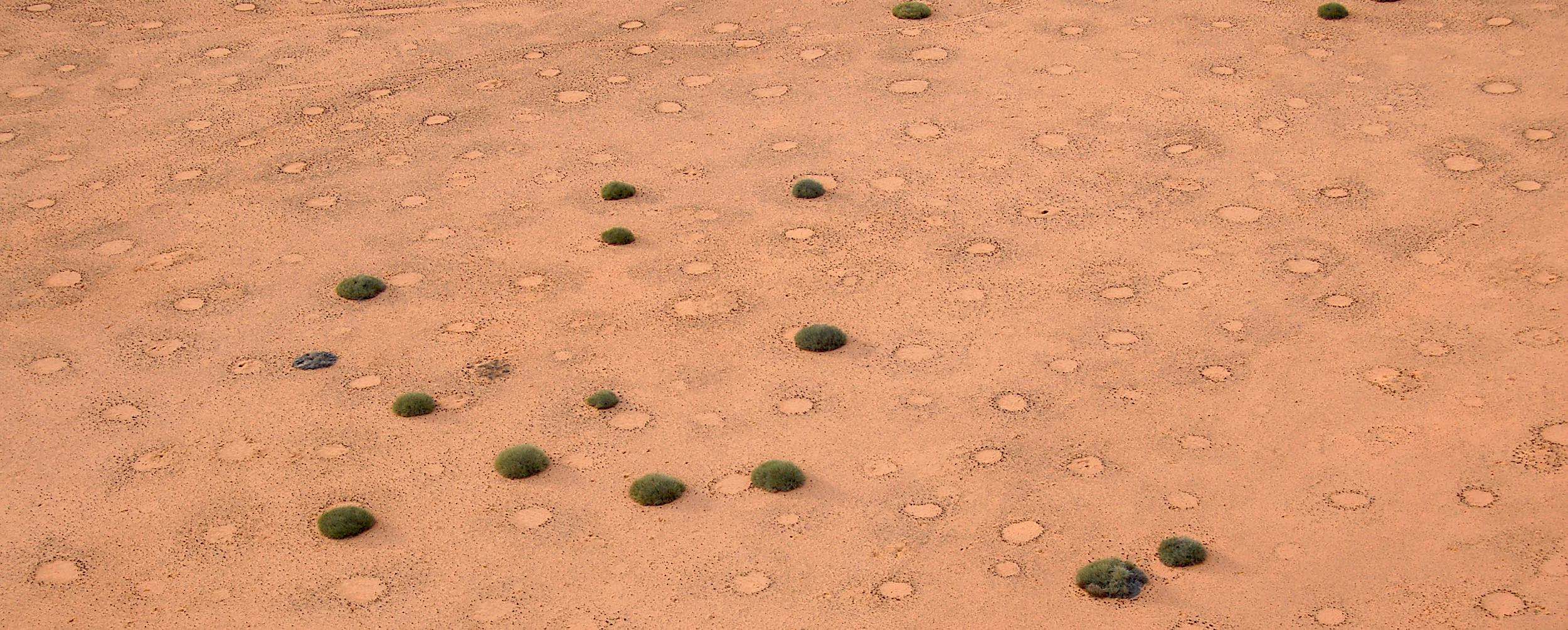

Fairy circles in the Namib Desert have fascinated people for centuries – from Himba traditions to more recent scientific theories, we have formed numerous different explanations for how these enigmatic circles of sand came into being. Several recent theories revolve around competition among plants or termites, or both. A scientific study last year went back to one of the original theories for fairy circle formation, and found some compelling evidence to support it.

Fairy circles have several features that must be explained by any proposed cause – they occur in regular patterns, they are often almost perfect circles (although some big ones are more oblong in shape), the centre of the circle is totally bare, whilst it is often ringed by denser stands of grass than the immediate vicinity. Water also behaves strangely in the circles – it disappears rapidly from the surface, only to settle at a greater depth and maintain higher soil moisture than it does in the rest of the landscape. The circles also seem to appear and disappear over time, although how long the circles actually last is debatable. Finding a cause that explains all of these strange qualities has had scientists scratching their heads for decades.

The leading theories thus far have relied on causes that are invisible to the casual observer – tiny, nocturnal termites living under the circles, or unseen competition among grasses living on the edge of the circles. By contrast, a theory that was initially proposed in the late 1970's involves a very conspicuous group of desert plants – Euphorbias.

These large desert succulent bushes are the ultimate desert survivors, often the only green thing to be seen in the red desert of western Namibia. Euphorbia stems and leaves contain milky latex, from which they have earned the Afrikaans common name melkbos - milk bush

. These bushes are critically important for black rhinos and other desert-dwelling herbivores that can eat these plants without suffering ill effects (by contrast, the latex is extremely toxic to humans). Importantly, as far as fairy circles are concerned, Euphorbias have a circular growing area.

Despite their dominant presence in the desert and the early theory, Euphorbias have largely been overlooked in the search for the fairy

that causes strange circles in the desert. Professor Marion Meyer of the University of Pretoria in South Africa, along with three of his students, recently revived the Euphorbia-fairy circle theory with some thorough investigations. They wanted to find out if Euphorbias could answer the most vexing fairy circle questions – Why does water behave so strangely in the circles? What prevents plants from growing in the circles? Why are fairy circles so regularly spaced in the environment?

The first two questions involve the soil, and the answer came from the characteristic milky latex produced by every species in the Euphorbia plant genus. The researchers ran numerous tests on the behaviour of water in soil laced with Euphorbia latex, and found that water disappeared quickly through the soil, or skimmed over the top (the latex-infused soil itself becomes hydrophobic and thus repels water – either forcing in further downwards or across the surface of the soil). Water that went down into the fairy circle seemed to follow paths that might have been made by the root system of the now-dead Euphorbia plant. The dense grass growth on the edge of the circle is caused by water moving across the surface of the soil. Just like the lush grass you see on the edge of tar roads – because water moves over the tar road it effectively waters the grass next to it. Yet in the centre of the circle, water settles so far down that it is out of reach for the roots of small grass plants.

In another experiment with latex-coated soil, the scientists found that grass seeds did not germinate when very limited water was provided (simulating the usually limited rainfall in the desert), but managed to do so when more water was available. In unusually wet years, one can find a few young grass plants trying to grow in the centre of fairy circles, but they soon die due to the lack of water for their shallow roots. The influence of water on germination may also explain why fairy circles don't occur in wetter areas, even though Euphorbia species grow there.

Finally, the research team found that the soil chemistry created by a dying Euphorbia bush interfered with the bacteria found in grass roots that are important for growth. In short, grass plants don't stand a chance in the centre of a fairy circle, but have a great time of it at the edge.

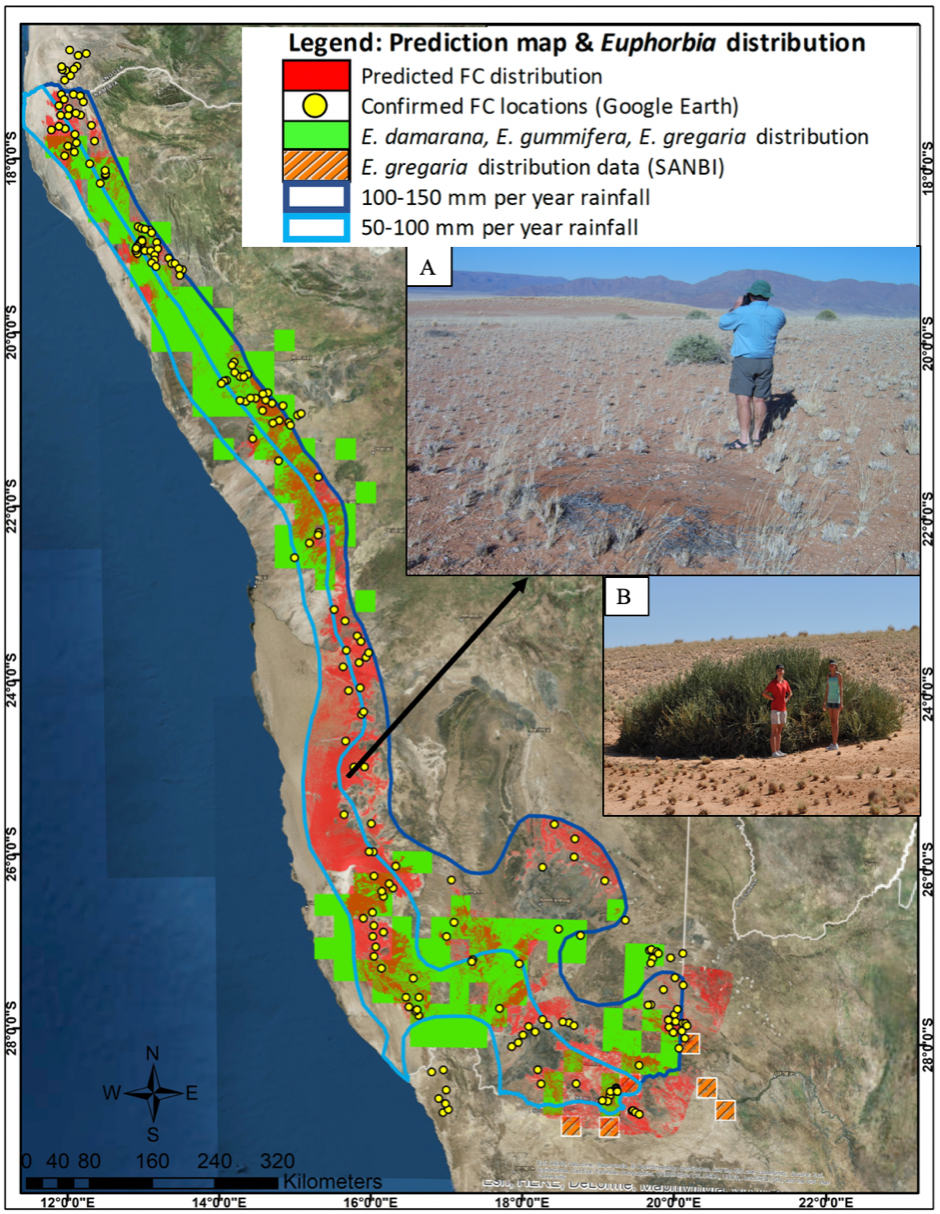

To figure out why fairy circles are so evenly spaced in the landscape (rather than bunched together), the researchers mapped populations of Euphorbia bushes in three different parts of Namibia and compared these with sites where there were mixed live bushes and circles, and sites with circles only. They found that areas where the bushes were struggling to survive showed similar spatial patterns to fairy circles. The pattern is therefore a result of the bushes competing with each other for water in sub-optimal habitats.

One of the strongest pieces of evidence the scientists found for their Euphorbia-fairy circle theory was their ability to predict where else fairy circles could occur. The previously known fairy circle distribution is limited to a strip of land running parallel to the Atlantic Ocean from south-western Angola through western Namibia and into north-western South Africa. By applying their theory of ideal conditions for fairy circle formation (amount of rainfall, altitude, grassland vegetation and soil type), they predicted that fairy circles could occur further east – across southern Namibia and into the Kalahari Desert in South Africa. Following their model, they studied these areas on Google Earth and, lo and behold, found previously unknown fairy circles!

Although fairy circles are well known in the sandy parts of the Namib where grasslands predominate, Prof. Meyer and his team noticed a similar phenomenon in rocky parts of the desert. Instead of grass-ringed circles, they found sandy circles surrounded by rocks. Following careful investigation, they concluded that living Euphorbia plants in rocky deserts trap sand that is carried in the air during windstorms; this sand accumulates underneath the plants over time. When a plant dies, it leaves a circular layer of sand on top of the rocky substrate that has very similar chemical characteristics to the sand found underneath living Euphorbia bushes.

A large portion of the Namibian strip of fairy circles occurs far from living Euphorbia bushes, which casts some doubt on this theory. The scientists, however, postulate that these areas could be Euphorbia graveyards, where conditions are no longer suitable for live bushes. If this theory is correct, then extensive fairy circle formation could reflect past climatic changes that made Euphorbia plants die off entirely in this area. Given that climate change models predict that Namibia will become even drier in future, this finding is cause for some concern. If the Euphorbia bushes die out, there will be almost no food left for black rhinos and desert-adapted antelope in the Namib Desert.

Given the nature of scientific discovery, there will no doubt be many more studies on fairy circles in future that will either strengthen or weaken this theory with new evidence. It is possible that the termites that are very associated with fairy circles are helping to maintain them by killing off any grass that manages to survive in the inhospitable soil. Or perhaps the termites are just capitalising on the high moisture content enabled by the dead Euphorbia root system? For now, let's accept that nature's fairies come in surprising forms.

Reference: Meyer, J.J.M. et al. (2020). The allelopathic, adhesive, hydrophobic and toxic latex of Euphorbia species is the cause of fairy circles investigated at several locations in Namibia. BMC Ecology 20:45 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-020-00313-7

A rebuttal to this article, disputing the claim that dead euphorbia bushes cause fairy circles, was published by Conservation Namibia under the title: The Plot Thickens - Euphorbia bushes do not cause fairy circles.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this article, then you might also like:

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.orgThe Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.org

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

Share:

Subscribe

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.