Managing Namibian Rangelands in the Face of Uncertainty

Agri-Ecological Services

2nd December 2020

It's that time of year again in Namibia, when everyone starts obsessing about the weather. Will this rainy season finally break the multi-year drought? Will most of the rains fall early or late? If you're in the city, the question is fairly simple – will the dams fill up and ease water restrictions? But if you're a farmer, you have a lot more questions – answering them correctly can make a huge difference to your livelihood and the land you farm.

The key issue is that Namibia's climate is not just dry, but its rains are highly variable and unpredictable. The rains may fail almost entirely one year, only to cause severe flooding the next. Any given farm can get much more (or much less) rainfall during the year than its direct neighbours. Long-term seasonal forecasts for Namibia, particularly at the scale of individual farms, are therefore poor guides for land managers who want to know when and where rain will fall. Farming in Namibia can feel like playing roulette: you guess the odds of success, place your bets and hope that the spin of the wheel is favourable this year.

Farmers have their own experience to draw from and an intimate knowledge of their land, yet decisions on how many animals (including game species) to keep on the land each year are far from straightforward. Different species of livestock and game animals use the veld differently (e.g. eating grass, leaves, or both) and different parts of the farm may have received more or less rainfall. Once the rainy season draws to a close in April or May, farmers need to place their bets

by selling and/or culling, or investing in more animals.

If too many animals were kept, then as the dry season approaches its end in October or later (when I hope it rains soon!

becomes the national motto) animals get lean and may even die, unless the farmer buys feed or moves them to land that has a bit more grass. These are expensive options, as demand for fodder and grazing land leads to high prices for keeping animals alive. Selling lean animals at a time when everyone else is selling means letting animals go for depressingly low prices.

While these annual decisions affect farmers' livelihoods in the short-term, years of making poor decisions will take a toll on the rangeland itself. If the soil is left bare due to continuous over-grazing, erosion will remove the nutrient-rich topsoil and make it difficult for grass plants to re-establish themselves. Thorn bush may take the grasses' place over time, thus reducing productivity for grazing animals. When rangeland degradation is added to the effects of climate change, the odds of farming successfully are likely to decrease over time.

This is why the Rangeland Monitoring Project implemented by Agri-Ecological Services is such a critical and timely intervention. This project brings accurate vegetation data from space to the farmer's fingertips. Satellites launched by the USA and the EU continuously collect information on different light wavelengths emitted from the earth's surface (this is known as remote sensing). Growing plants emit different light at different wavelengths to non-growing plants or bare soil and rock. In simple terms, this means that satellite data (after analysis and mapping) can tell a farmer in Namibia where the most plant growth is occurring on their farm right now and how that compares with other farms around them and previous seasons.

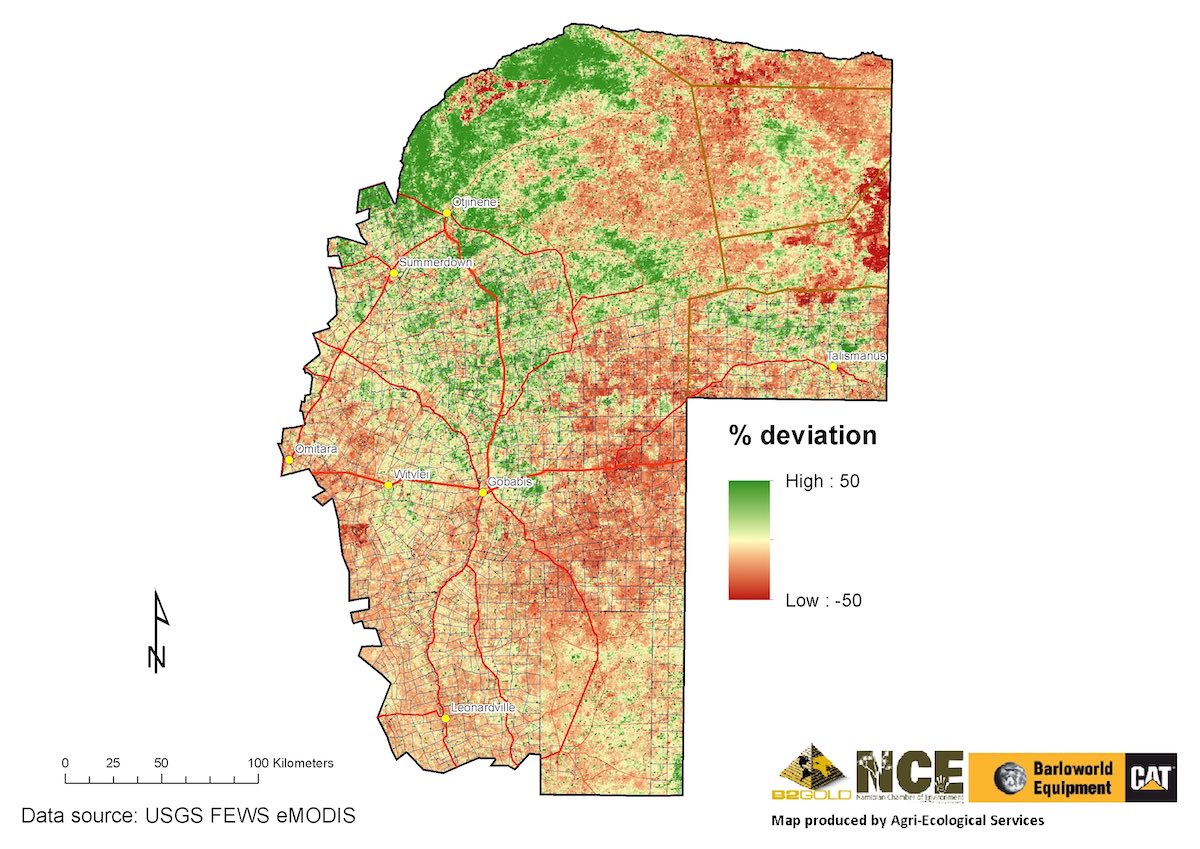

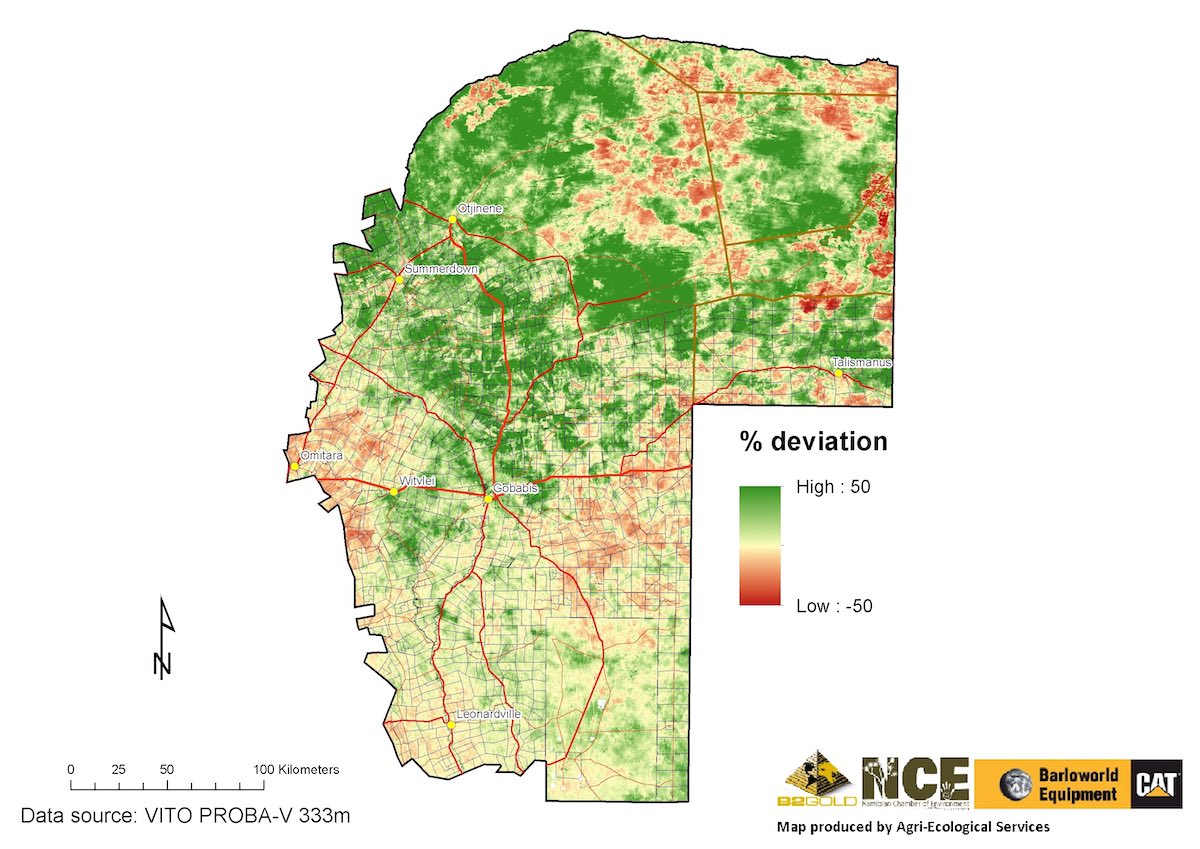

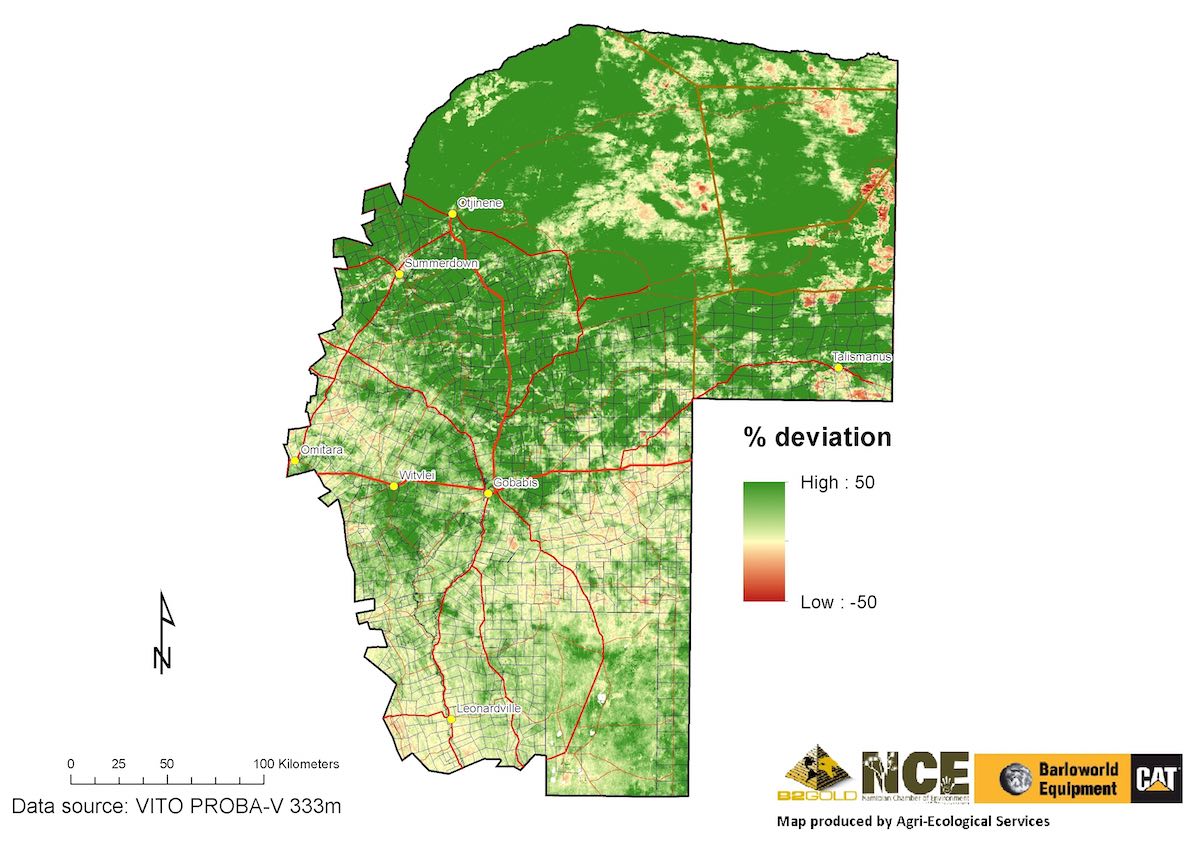

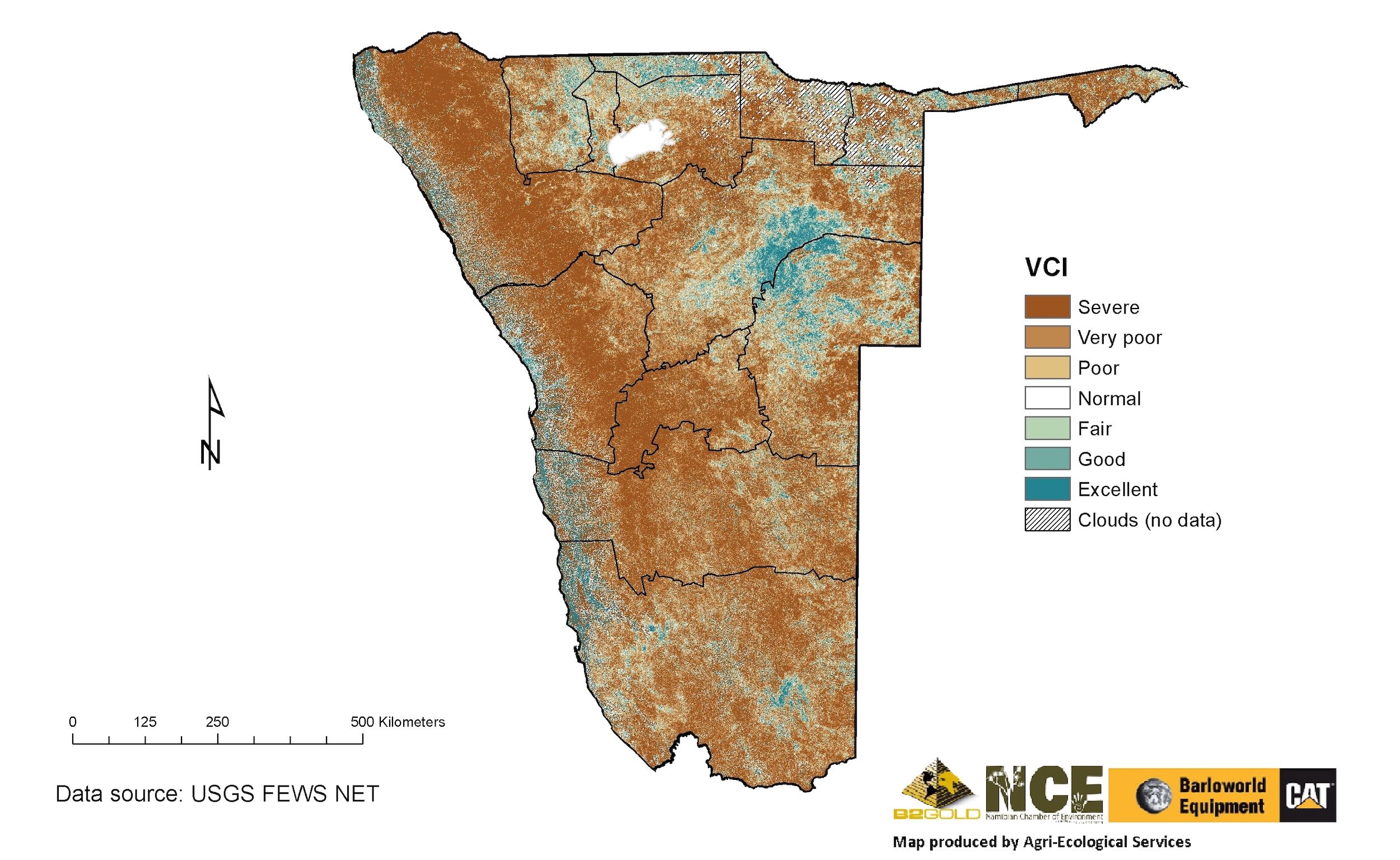

The Rangeland Monitoring website uses remote sensing data to produce maps every ten days during the rainy season (October to May). The maps cover each region of the country and some special areas of interest (e.g. Etosha National Park), with overlays of freehold farm boundaries, towns and roads. For farmers, this means you can find your farm easily and compare it with others in the country.

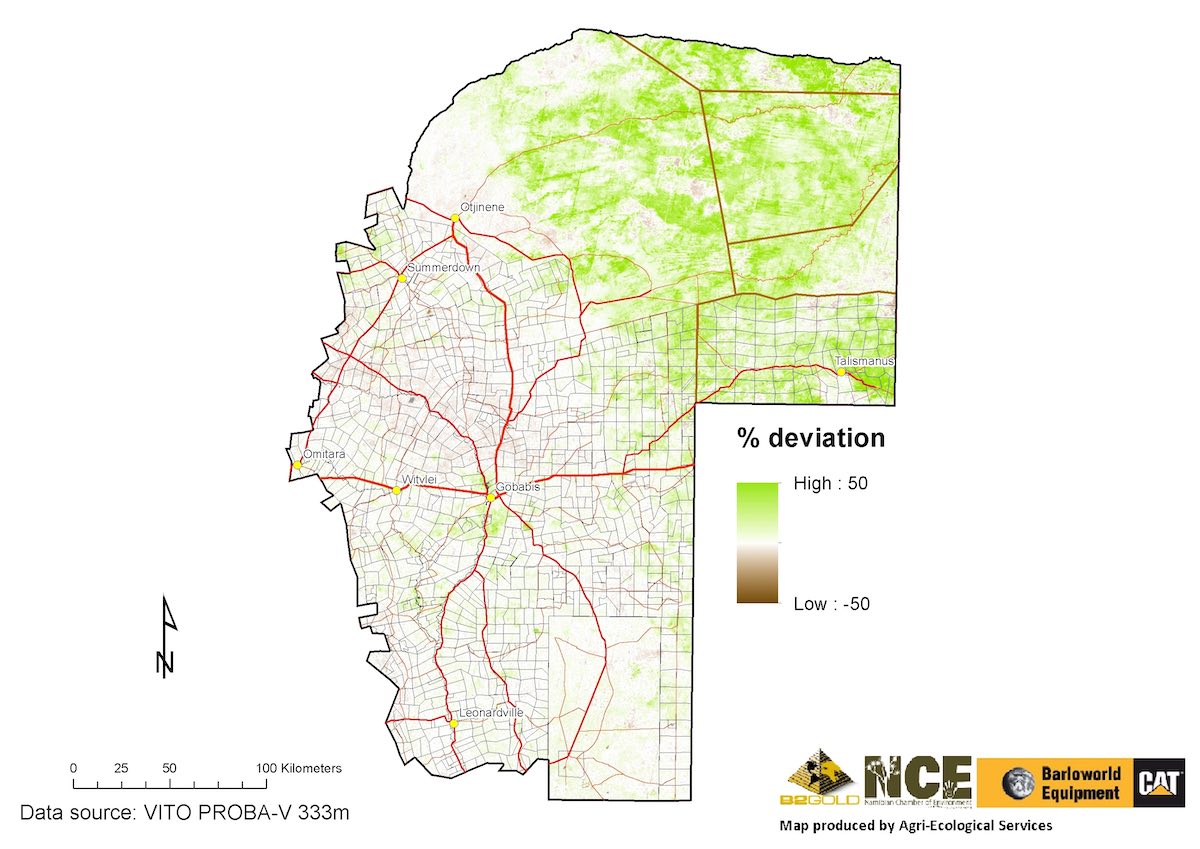

Four maps are produced for each region that compare the current data with: 1) the average data since 2002; 2) average data from the previous four years; 3) the previous year; and 4) the data from 10 days ago. The first three maps are for the same time of year in those previous periods, so one can compare the performance of this rainy season's plant growth directly with historical performance. The map comparing current growth with ten days earlier provides a trend for this season – is plant growth increasing rapidly as the rainy season goes on (a good sign!), or is it stagnating (early warning for a poor season)?

A fifth map that is sent out to email subscribers every 10 days during the rainy season compares the current condition of the vegetation with the range of possible vegetation states recorded at the same time in previous years (going back to 2005). This map shows you how well the vegetation is doing this year relative to historical data. Read alongside the other four maps, you can get a pretty good idea about how good or bad the coming dry season will be and (if you're a farmer) what can be done about it. With all this knowledge gained during the season, plus personal observations and actual measurements of the grass available at the end of the growing season on the farm, farming can become more like science and less like gambling.

A recent survey of 100 site users (64 freehold farmers, 18 communal farmers, 17 emerging farmers and 15 other interested parties) revealed that two-thirds of the respondents found the information useful or very useful for their purposes. Of these respondents, 51% used it to monitor their rangelands, 23% to help plan their management activities and 10% used it as an early warning for drought. Farming consultants also used it to advise their clients, whilst one respondent used it to find out where medicinal plants were likely to be growing in Namibia. The last response gives us an enticing glimpse of diverse potential uses for this information, while the many positive user responses certainly encourages the project to keep going.

This five year-old project, initially supported by the European Union (EU), Agribank and Agra ProVision, recently received a grant from the Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) to expand its scope and target users. Besides continuing the service to farmers and other interested people countrywide, NCE's grant (made possible with funding from B2Gold and Barloworld Equipment) will be used to expand the application for use in protected areas. The Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) will thus receive the kind of data they need to monitor and manage their Parks and Reserves effectively. Communal conservancies supported by the Namibian Association of CBNRM* Support Organisations (NACSO) have received similar data tailored to their needs since 2016.

The information in these maps is just one tool that provides an objective assessment of current plant growth. It does not replace the farmer's own observations on the ground or knowledge of the farm, but rather supplements it. One of the key tasks for land managers is to be proactive and adapt to the conditions as quickly as possible, which is the only way to survive in a highly variable environment that will be increasingly affected by climate change. The challenges that Namibian farmers and other land managers face are daunting, but they need not face them alone.

* CBNRM = Community-Based Natural Resources Management

You can view maps of the current season's vegetation growth and sign up for the emails to update you when new maps come out during the rainy season via

http://www.namibiarangelands.com, or

email rangemonitor@gmail.com

directly. A mobile application has also been developed to help farmers determine the ideal stocking rate at the end of the rainy season using your own inputs – search for Rangeland Fodder Flow Planner

on the Play Store (Android) or App Store (Apple).

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

Agri-Ecological Services was founded in 2010 by Dr van der Waal and has implemented several projects alongside other partners including: rangeland health assessments, developing monitoring systems, including the rangeland early warning system, applied remote sensing and assisting with biodiversity assessments such as NamPower's bush-to-power project.

http://www.namibiarangelands.comAgri-Ecological Services was founded in 2010 by Dr van der Waal and has implemented several projects alongside other partners including: rangeland health assessments, developing monitoring systems, including the rangeland early warning system, applied remote sensing and assisting with biodiversity assessments such as NamPower's bush-to-power project.

http://www.namibiarangelands.com

Dr Cornelis van der Waal is an ecologist with a passion for rangelands and their wise use. He holds a PhD in Resource Ecology with a background in Grassland Science (MSc) and Wildlife Management (BSc Honours). Currently, he is leading a team of scientists to revise Namibia's agro-ecological zones and carrying capacity maps. He and his family live close to Omaruru.

Dr Cornelis van der Waal is an ecologist with a passion for rangelands and their wise use. He holds a PhD in Resource Ecology with a background in Grassland Science (MSc) and Wildlife Management (BSc Honours). Currently, he is leading a team of scientists to revise Namibia's agro-ecological zones and carrying capacity maps. He and his family live close to Omaruru.

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.