Namibia and South Africa share the Succulent Karoo Biome – one of only two arid biodiversity hotspots in the world. The South African side of the biome has been used more intensively than the Namibian side, revealing what happens to this ecosystem under different land uses. Recent scientific results from South Africa present a cautionary tale for Namibia, especially as we consider the future of Tsau //Khaeb (Sperrgebiet) National Park.

The Richtersveld case study

The northernmost part of South Africa's Succulent Karoo is known as the Richtersveld. Part of this roughly 10,000 km2 ecosystem falls under a national park, which is managed by South African National Parks (SANParks) under a contractual agreement with the local community. Unlike most other parks, Richtersveld NP is still inhabited by people and their livestock. Mining is allowed in some parts of the park and continues along its borders and in the non-protected parts of the wider ecosystem.

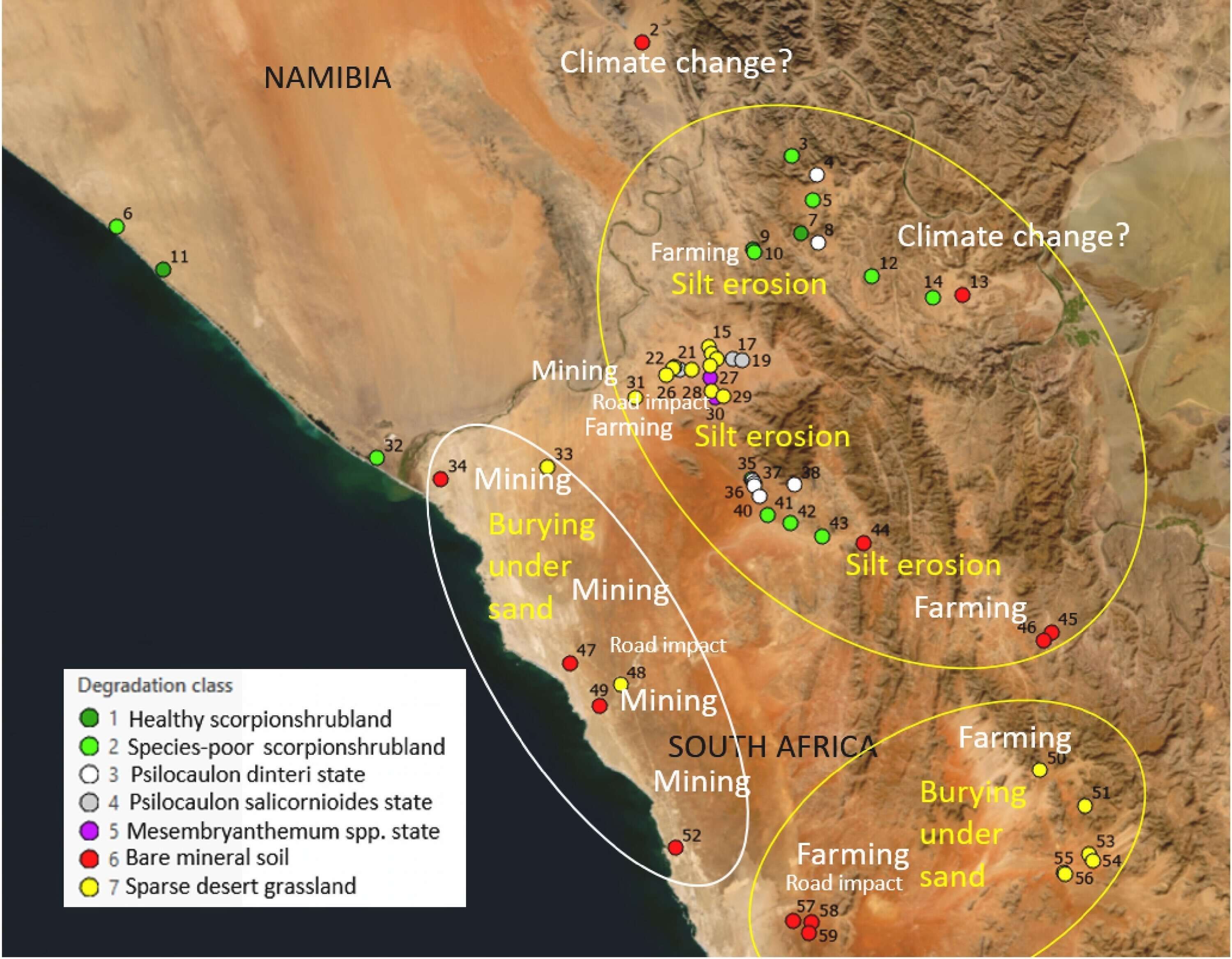

A recent study by Prof Norbert Jürgens and colleagues reveals that the Succulent Karoo in this area has been slowly degraded over the last 45 years, with a recent severe drought (peaking in 2019) tipping some parts of the ecosystem over the edge. That 'edge' is the invisible line between a species-rich, succulent-dominated ecosystem and a species-poor, grass-dominated desert. If this trend continues, the biodiverse Succulent Karoo may be swallowed by the Namib Desert.

The recent drought may be a harbinger of more to come, especially if the climate change predictions for South Africa and Namibia are realised. The combination of reduced rainfall and increased heat pushes succulent plants to their limits, resulting in prominent species like Quiver Trees and Euphorbias (melkbos) dying out in the hottest and driest parts of their ranges. The Richtersveld study confirms this worrying trend for the less well-known plants that characterise the Succulent Karoo. A few of these unique species are already extinct in the wild.

While drought and heat are obvious threats, Jürgens and his colleagues found signs of long-term degradation prior to the drought that create more insidious threats: a change in vegetation and soil properties resulting in loss of silt and more sand movement. Although they could not show a change of general wind conditions during their study period, they found that wind is now picking up more sand than before and blowing it over the landscape. This is especially true around highly disturbed areas: livestock kraals, watering points, mining areas (including old dumps and trenches), ploughed lands and roads (both dirt and tar).

When the ground is cleared of vegetation around these areas, the soil is loosened and is more easily picked up by the wind. Huge plumes of sand can be seen blowing into the ocean on satellite images, while the researchers found smaller plumes for several kilometres around disturbed areas inland. The plants in these areas are frequently sandblasted, damaging their leaves. In extreme cases, plants are buried alive and eventually die due to lack of sunlight.

The accumulation of sand changes the ecosystem in yet another way – by changing the soil type. Since succulent plants prefer growing on silty soils (a texture between sand and clay), while grasses that are common in the Namib Desert prefer sandy soils, the increasing sandiness has allowed grass to take over. This change makes it difficult for succulents to re-establish themselves, even in years of good rainfall, which is why Jürgens and co-authors warn that this level of desertification could be irreversible.

While the disturbed sites were restricted to a few square kilometres each (e.g. around an old mine, road or kraal), the large number of such sites results in vast areas being buried in sand—particularly in the prevailing wind direction. Beyond these areas, the authors noted signs of widespread degradation and an overall loss in the number of plant species found in the Richtersveld during the last few decades.

Lessons for Namibia

On the Namibian side of the Orange River, most of the Succulent Karoo falls within the Tsau-//Khaeb (Sperrgebiet) National Park. As a Forbidden Area

surrounding diamond mining activities, the Sperrgebiet kept human activity to an absolute minimum in the unmined parts of this zone for nearly a hundred years. Unsurprisingly, the Richtersveld study authors noted that the vegetation in what is today the Tsau //Khaeb NP had not experienced the kind of degradation found on the South African side of the border.

Despite its designation as a national park in 2004, the future of the Tsau //Khaeb looks uncertain. The largest looming threat is the development of extensive infrastructure for green hydrogen production. If this project and others like it go ahead, the area will be covered in solar panels and wind turbines, with roads leading to each solar farm, turbine and electricity pylon for maintenance purposes.

When vegetation is cleared to make way for these roads and other infrastructure, it will loosen the soil and create the conditions for wind erosion. This area is known for its windiness, which is what makes it attractive for green hydrogen development in the first place. As we now know from the Richtersveld, disturbed land plus wind is a recipe for disaster.

The plants around each road, solar farm and wind turbine will be sandblasted or buried. If the green hydrogen plans are fully realised – with infrastructure covering most of the Tsau //Khaeb NP – much of Namibia’s Succulent Karoo may be replaced by desert, driving many endemic plants to extinction in the process.

Conclusion

The recent study on South Africa's Richtersveld reveals how vulnerable the Succulent Karoo is to disturbance. Given the high numbers of endemic plant species (and even less well-known numbers of endemic reptiles, insects and other wildlife), any development here should be subject to careful planning. Even if the area is used for low impact tourism, as per the original management plan for the park, infrastructure should be kept to a minimum.

As the Namibian Chamber of Environment argued in the When Green Hydrogen Turns Red

position paper, any plans for developing extensive hydrogen infrastructure in this sensitive ecosystem should be disbanded. There is a good reason why the Tsau //Khaeb National Park was established—it protects globally important biodiversity, a fact which was not adequately considered by Namibian policy-makers when areas for 'green hydrogen' development were allocated.

Instead, the Namibian government has opened this sensitive area to the whims of developers from Europe. Namibia should not have to destroy its biodiversity to address the energy failures of Germany and other EU countries, or help them solve the climate problems they have caused. These countries often fail to appreciate that the loss of biodiversity and the damage to ecosystems, ecosystem services and landscape functioning is the largest environmental threat facing humanity and the planet. Once species are extinct, they are gone—for good.

Climate change is arguably the second largest threat, and addressing it should never be done at the expense of biodiversity. While efforts to combat climate change and develop renewable energy remain important, Namibia should not bury its unique biodiversity in the process. And Germany and other EU countries must not incentivise such actions.

Read the original scientific paper here.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.