Many Namibians hail from the regions north of Etosha, formerly called Owamboland, but today often referred to simply as the North

. While the towns in the North have grown rapidly in the last couple of decades, up until about 50 years ago this area used to have only rural farms and villages, with most inhabitants leading a subsistence lifestyle.

Despite its current socio-economic importance for so many Namibians, surprisingly little is known about this ecosystem, which scientists call the Cuvelai wetland system. It also has many fascinating features, many of them enigmatic.

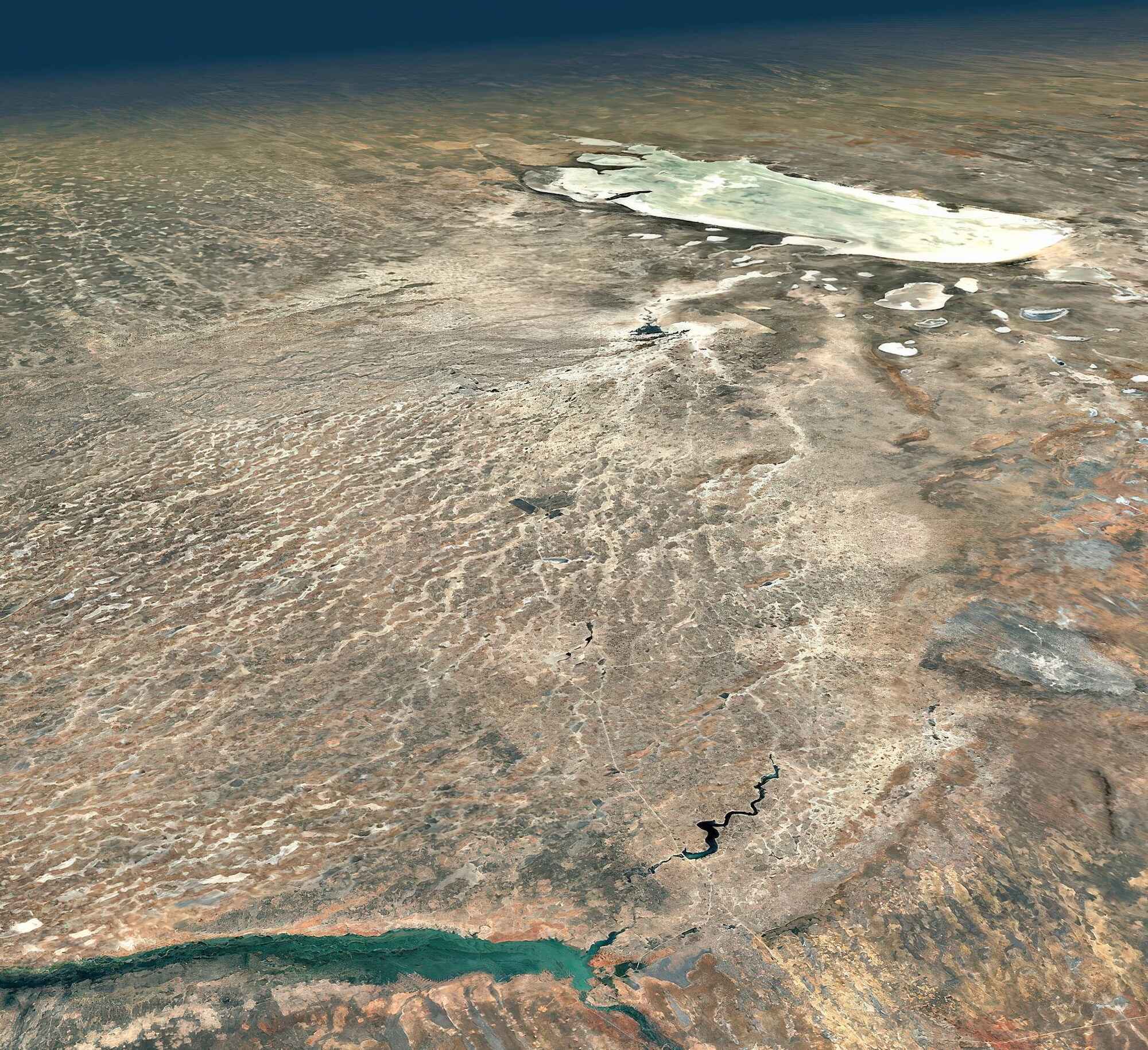

The Cuvelai is shared with Angola, both sides of the wetland system supporting many more people than in nearby rural areas. Residents often have strong ties with relatives across the border, and thousands of people cross the border each day. Rivers that start in Angola flow south, splitting and merging many times in hundreds of narrow water channels known as iishana in Namibia and chanas in Angola. At its widest, the network of channels is about 180 km wide between Mahanene in the west and a little beyond Odibo in the East, both within Namibia. Particularly strong flows – known as efundas - can lead to widespread flooding but they also deliver great bounties of fish which are harvested by local residents.

The drainage lines eventually join into a few major channels. When flows are strong, water in these channels may flow all the way into the Omadhiya Lakes, and then down the Ekuma River into Etosha Pan. This is as far as the Cuvelai's water ever goes, and that makes the Cuvelai an endoreic wetland system (like the Okavango and Cuando rivers) – where surface flows eventually evaporate or seep away, thus never reaching the ocean.

Without the Cuvelai system, Etosha Pan would not exist. There is also good evidence that the entire Kunene River once flowed into the Cuvelai where it filled a gigantic lake that filled Etosha and areas extending north across the border into what would become Angola thousands of years later.

Other enigmatic features of this system include: 1) a major river that runs along the top of a ridge, unlike in a valley where most rivers belong; 2) people prefer to settle and establish fields on the western side of wetlands rather than the east; 3) many alluvial fans or deltas are dotted across the landscape; and 4) the bottoms of the upstream Omadhiya Lakes are lower than the downstream Etosha Pan.

In short, this multi-stemmed drainage system is globally unique. In a recent scientific paper, John Mendelsohn and Martin Hipondoka highlight some of the key features of the Cuvelai wetland, including those that need further study.

From an ecological point of view, the Cuvelai’s wide open grasslands, hundreds of iishana and about 190,000 of pans that may fill with seasonal rain are an important feature of Namibia. People and their crops and livestock have used this land for millennia, while an untold multitude of birds, amphibians, fish and other animals rely on the seasonal wetlands for breeding and sustenance. Although Etosha’s wildlife are well-studied, little is known about the wildlife living elsewhere in the Cuvelai.

The changes to this landscape over time are also worth further study. Geologically, small tectonic shifts have influenced the flow of water from north to south. On a socio-economic level, the changes have been far more rapid and noticeable. The human population in northern Namibia grew substantially from immigration during times of economic hardship and civil war in Angola. As a result, woodlands were cleared for building material and firewood more rapidly on the Namibian than the Angolan side of the Cuvelai.

The resulting difference in land cover was clearly visible on satellite photos for decades, but it is now becoming less conspicuous, as Angola’s population grows and clears more land for shifting agriculture, and wood for building and heating. By contrast, the rural economy on the Namibian side is shifting from subsistence to commercial as increasing numbers of people use incomes from other sources to feed, warm and house themselves. With less clearing of new fields and wood harvesting the environment on the Namibian side is regaining some of its original natural woodland cover and health.

Many Namibians are now also living in towns. But larger towns come with other, more concentrated impacts on the environment, which includes the relatively new threat of pollution. Plastic and other waste accumulating in and moving through the iishana contaminates the whole system, affecting people, livestock and wildlife. Better urban planning, waste management and sanitation are needed to ensure that these new cities limit their environmental impact as much as possible.

It is clear that studying the Cuvelai is not merely for academic purposes. Investigating the effects of past events and monitoring the current state of the ecosystem can be used to project future scenarios that will impact the lives of many Namibians.

The Cuvelai is the cultural hub and historical home of the Owambo (aka Ambo) people, a centre for economic growth, an important social link with Angola, and a fascinating wetland that supports people and wildlife. For all these reasons and more, its natural resources deserve more study and proper management.

If you want to find out more about the the Cuvelai, start by reading this scientific paper by John Mendelsohn and Martin Hipondoka. The paper concludes with this wish: We hope that these questions whet the enquiring appetites of students and scientists to unravel more of the unusual structure and functioning of this rare environment.

You can also reach out to the authors of the paper to find out more.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.