The Lions of Etosha: A Brief History

21st March 2023

Etosha National Park is the best-known protected area in Namibia and is part of nearly every tourist's must-see list when visiting the country. As with most parks in Africa, Etosha's history is bound up in colonial management styles and priorities. Decisions about how to manage it and where its boundaries were drawn were influenced by numerous factors that had little to do with biodiversity conservation. Future management decisions must take history into account while charting a way forward for this iconic protected area.

As the park's apex predators, lions have been monitored or at least noticed (before monitoring was introduced) over a large period of the park's history. Management decisions, particularly relating to fences and water points, have directly affected lion prey with some counter-intuitive outcomes for lions. Attitudes towards lions have changed dramatically over this period: from vermin that were shot on sight along the park's boundaries, to one Etosha's main tourist attractions. Meanwhile lion-farmer conflict beyond the park boundaries has been a near-constant feature for decades.

In a recent scientific article published in the Namibian Journal of the Environment, John Heydinger, Craig Packer and Paul Funston scoured the national archives, searched Namibia's Environmental Information System and collected published and unpublished papers and reports relating to lions in Etosha. Stretching from pre-colonial records of early European settlers hunting lions to the most recent lion survey conducted in 2018, this paper provides historical insights and food for thought.

From Game Reserve No. 2 to Etosha National Park

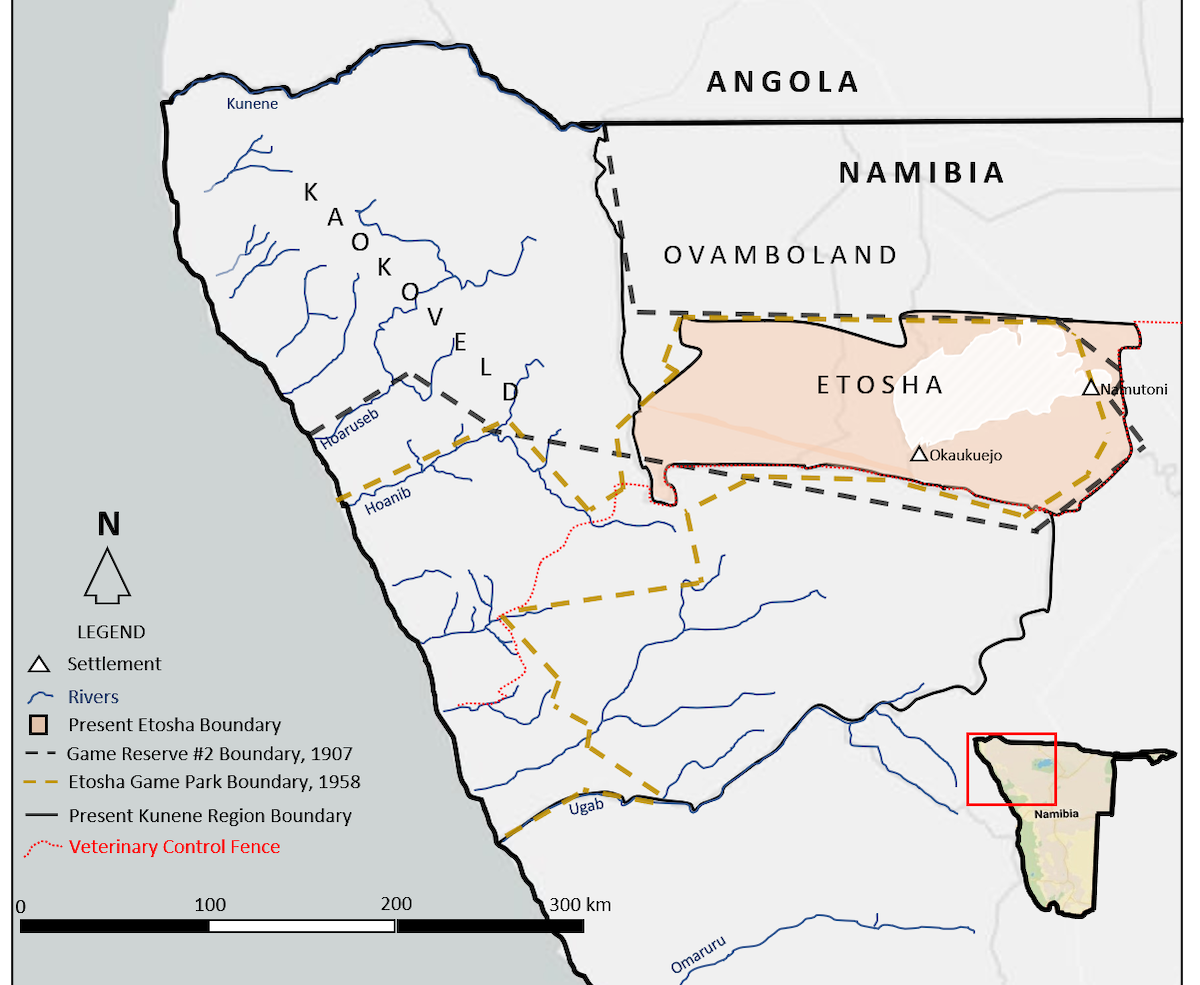

While present day Etosha National Park is an impressive 22,270 km2, the park was originally four times larger and went by the rather unimaginative name of Game Reserve No. 2

declared by the German colonial government in 1907. This huge reserve – the largest in the world at the time – incorporated the entire northern part of the Kunene Region that was later known as the Kaokoveld.

In 1958, the western boundaries switched from north to south, now covering most of the southern Kunene Region or what came to be known as Damaraland. This ‘new' reserve was known as Etosha Game Park that was managed by the proxy South West Africa government that ruled under the auspices of apartheid South Africa.

The major boundary shifts in these early days mainly involved drawing lines on a map, as the park was still unfenced. Colonial policies aimed to reduce the number of people and livestock in the area in favour of wildlife. The other related goal was to reduce disease transmission to livestock owned by white settlers living south of the park.

The Hai||om San people, who lived in the main tourism area around the pan and Okaukuejo were evicted from Etosha in 1954. Following the Odendaal commission in 1963 Kaokoland and Damaraland were designated as ‘homelands' and Etosha shrank to its current size in 1970. Today, Etosha is bordered to the north and west by communal lands and to the south and east primarily by freehold lands (some Hai||om have been resettled on farms south of Etosha).

Monitoring Etosha's lion population

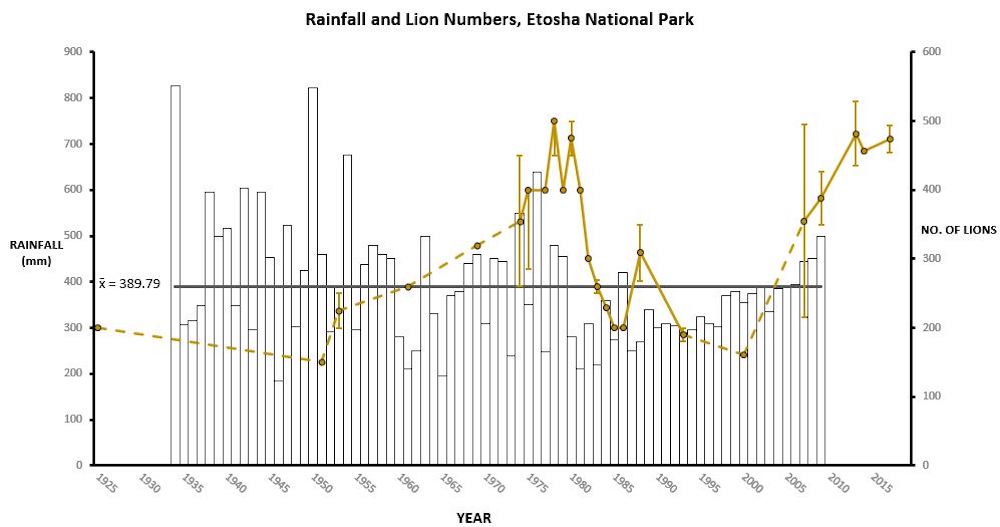

From the early 1900s to today, Etosha has undergone massive changes and ecological upheavals. Yet the lion population in Etosha has been surprisingly resilient, even though hundreds were shot on neighbouring farms in the early and middle parts of the 20th century. The lowest recorded estimate of lions in Etosha of 150 was in 1952, reaching a zenith of 500 in 1980, while the most recent 2018 estimate is 335.

The earlier lion estimates were based on the warden's knowledge of lion prides living in the more open savannah parts of the park and excluded the woodland areas to the west that were less accessible to park rangers. The numbers reported in Heydinger's paper draw largely on the work of control warden Hu Berry, who collated earlier reports and collected data himself to produce estimates covering nearly 70 years (1926-1994).

Philip Stander' lion monitoring work in the 1980s included the woodland areas of the park for the first time, producing the most detailed picture of the whole Etosha lion population to be obtained either before or since. Several Etosha-based ecologists and independent researchers have carried out more recent but less intensive surveys to keep track of overall trends.

The perfect ecological storm for lion prey

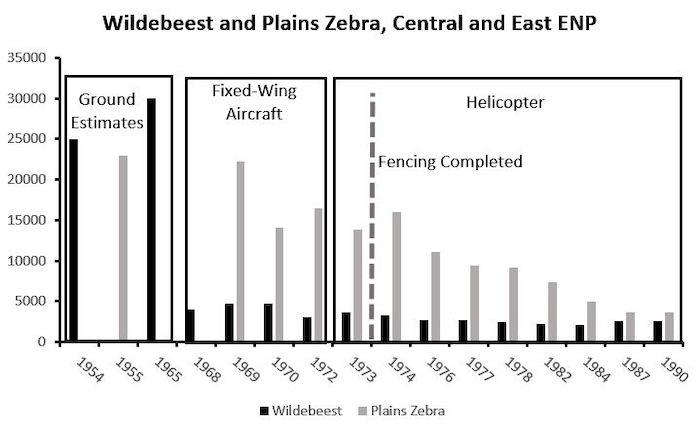

While lions have been directly affected by changes in management policies over time, the greatest impacts on this population have been indirect. Diseases, fences and artificial water holes combined to devastate the lion's key prey species: wildebeest and zebra.

The fences along the northern boundary of Etosha were particularly destructive, as they blocked migration routes and prevented large herds of wildebeest and zebra from returning to Etosha. The remaining animals clustered around newly created artificial water points, which were subsequently used throughout the year and over-grazed. Gravel pits created for road building became small dams that would hold water for longer into the dry season than usual, thus creating more ‘water points' and setting the scene for the next disaster.

Anthrax had always been part of the Etosha system, but over-grazing and soil disturbance related to road building led to major outbreaks around this time. Due to these multiple stresses, the wildebeest population crashed from 25,000-30,000 to less than 5,000 within a decade, while zebra experienced a similar decline over a longer period.

Lions adapt, decline and stabilise

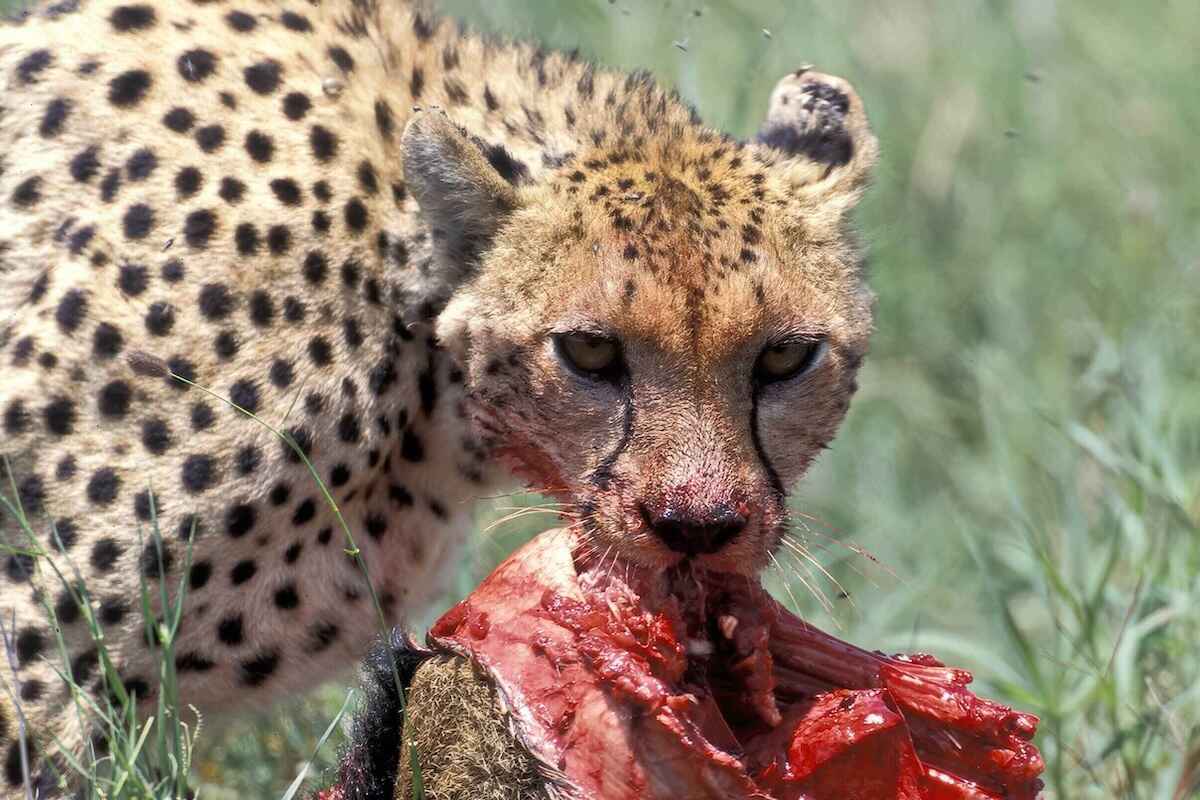

In the early years of this massive herbivore die-off, lions thrived. They are resistant to anthrax and could therefore feed on carcasses without harm. The creation of water points meant that their prey stayed in previously seasonal areas throughout the year, which allowed more prides to form stable territories in more parts of the park.

With their two main prey species reduced to fractions of their former numbers, the now abundant Etosha lions were in trouble. Springbok and, to a lesser extent gemsbok, saved them. In response to several good rainfall years, springbok numbers tripled to an estimated 32,000 in the late 70s, thus extending the good times for lions.

Lion diets switched from 80% zebra and wildebeest in the 70s to to 62% springbok in the 80s. The large numbers of lions were nonetheless a cause for concern for the few remaining zebra and wildebeest, leading Hu Berry to experiment with contraception to limit the lion population.

In the early 80s, severe drought struck Etosha and the entire north-western Namibia. The springbok that had become the main prey species for lions now went into steep decline. The lion populations followed, from their all-time high of 500 in 1980 to 200 in 1986. Since then, lions have increased slightly and stabilised to around 300-400.

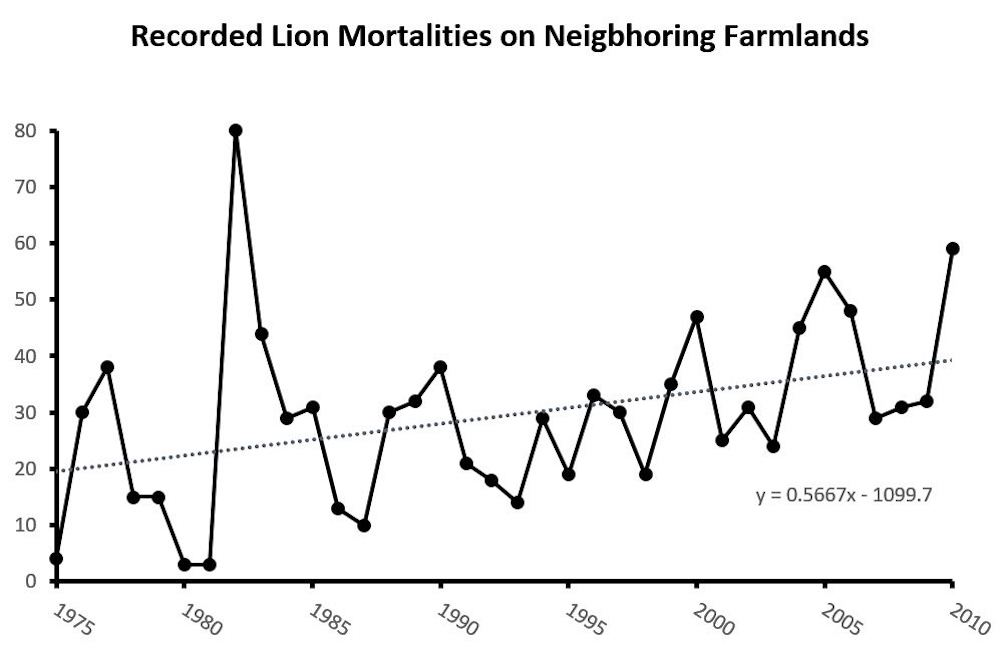

Besides the ups and downs lions experienced within Etosha, there has been one continuous source of lion mortality since the very beginning: human-lion conflict. During a 35-year period (1975-2010) at least 1,059 lions were killed, mainly on freehold farms on the southern and eastern boundaries. This reveals that the fences around Etosha serve as a hard barrier to lion prey, but not to lions that can still leave the park to prey on livestock and thus become vulnerable to farmer retaliation.

Reflections on the history of lions in Etosha

What can we learn from the history of lions in Etosha? This park has been a safe haven for a species that was all but exterminated on neighbouring lands. Yet all but cutting this ecosystem off from the land around it has been devastating for lion prey species. There would be many more lions if wildebeest and zebra populations had never crashed.

Although the lion population has stabilised over the last few years, monitoring remains important to allow us to continually evaluate management decisions. Extended drought periods related to climate change could pose another threat, so we cannot assume that the population will always be secure in Etosha. Lions have nonetheless proven to be resilient by adapting their movements and prey preferences according to changes in the ecosystem.

The socio-political landscape around Etosha has also changed dramatically. While the people living to the west of Etosha are no longer within the park, they have established communal conservancies that encourage mixed wildlife and livestock land use. Some of the freehold farms south of Etosha have switched from livestock to tourism, thus becoming increasingly lion-friendly.

The much-debated park fence has not eliminated human-lion conflict beyond its boundaries, but it does prevent cattle from entering the park and thus becoming even more vulnerable to predation. As we discovered when the fence was first erected, the effects of fencing are myriad and one should not take decisions about erecting or dismantling a fence lightly.

Human attitudes towards lions remain highly variable: from damage-causing nightmare to one of the world's favourite big cats, depending who you ask. Over the decades, conservationists have come to more fully appreciate the importance of factoring human needs and perspectives into the conservation equation. Etosha's lions will undoubtedly continue to be on the tourist's must-see list, but their future is firmly in the hands of Namibians – those entrusted to manage the park and those living next door.

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.orgThe Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.org

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.