Namibia's Directorate of Veterinary Services is strictly enforcing regulations that are an unnecessary, expensive, harmful and ultimately vain attempt to stop disease transmission between wildebeest and cattle. The current regulations do little to reduce the spread of disease to cattle, while limiting or even reducing the blue wildebeest population in Namibia.

A proper understanding of this disease will lead to more effective, cheaper and practical solutions to this issue that will benefit both the cattle and wildlife sectors. Namibia's national interests will be better served if the Directorate used this knowledge and practical suggestions from well-known Namibian wildlife vet Dr Ulf Tubbesing to change its approach.

Understanding snotsiekte in Namibia

Both wildebeest and sheep are carriers of the viral disease known locally as snotsiekte (officially, Malignant Catarrhal Fever). The term carrier

refers to animals that carry and transmit a disease without becoming sick themselves. Malignant catarrhal fever is a disease with a world-wide distribution where, in countries outside Africa, it is transmitted from sheep to cattle. On the African continent, Namibia included, wildebeest are the main source of transmission to cattle.

The good news is that few healthy cattle get sick and those that do, don't transmit it to other cattle. The bad news is that there is a high chance of death for the few cows that do get sick. The symptoms of the disease are easily confused with other diseases, but there are lab tests available that will confirm whether snotsiekte was the cause of death and, if so, whether it came from sheep or wildebeest.

Dr Ulf Tubbesing of Wildlife Vets Namibia analysed data from the Central Veterinary Laboratory in Windhoek covering the last six years (2018 to early 2024), and found only 26 cattle contracted snotsiekte from wildebeest (at a rate of 4-5 cases per year). Other cases may have been missed if samples from sick animals weren't submitted for appropriate lab tests. Nonetheless, cases of suspected snotsiekte reported to the Department of Veterinary Services are also low, and statistics show that around a quarter of these are misdiagnosed (of every four samples submitted as suspected snotsiekte, only one is positive).

The prevalence of snotsiekte in Namibia is much lower than in South Africa, possibly because of Namibia's hot and dry conditions that kill the virus quickly after it exits the host. In order to spread from wildebeest to cattle, the virus first has to be shed from its host, just like humans with COVID sneezing on a door handle. The virus must then survive outside the host for long enough for another victim (in the case of snotsiekte, a cow or other animal) to pick it up.

Unlike COVID, this virus seems to have more than one way of infecting a new host. There are multiple known cases of cattle being infected with the disease when the nearest wildebeest was several kilometres away! This has led vets to conclude that flying insects are probably transferring the virus from one species to another. A mere 10 metres of separation between cattle and wildebeest will not prevent transmission by insects.

Other important factors are the stress levels and health of both wildebeest and cattle. Studies from South Africa indicate that wildebeest seem to shed the disease during calving season and that calves are more likely to shed the disease than adults. If adults or calves are under stressful conditions (e.g. in a zoo or overstocked camp), they are more likely to shed the virus.

Cattle health is also important – as we found out with COVID, not all individuals that catch a virus actually get sick. The cow's immune system and overall health will help to protect it, which is why only a few cows in any herd will get sick even if the whole herd is exposed to the virus.

Current regulations are not fit for purpose

Knowing the prevalence of the disease and how it spreads is key to developing regulations that reduce cattle deaths and ensure that game and cattle farmers do not harm each other's operations. The current regulations enforced by the Directorate of Veterinary Services (operating under the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Land Reform) do not take any of the above information into account and therefore do more harm than good.

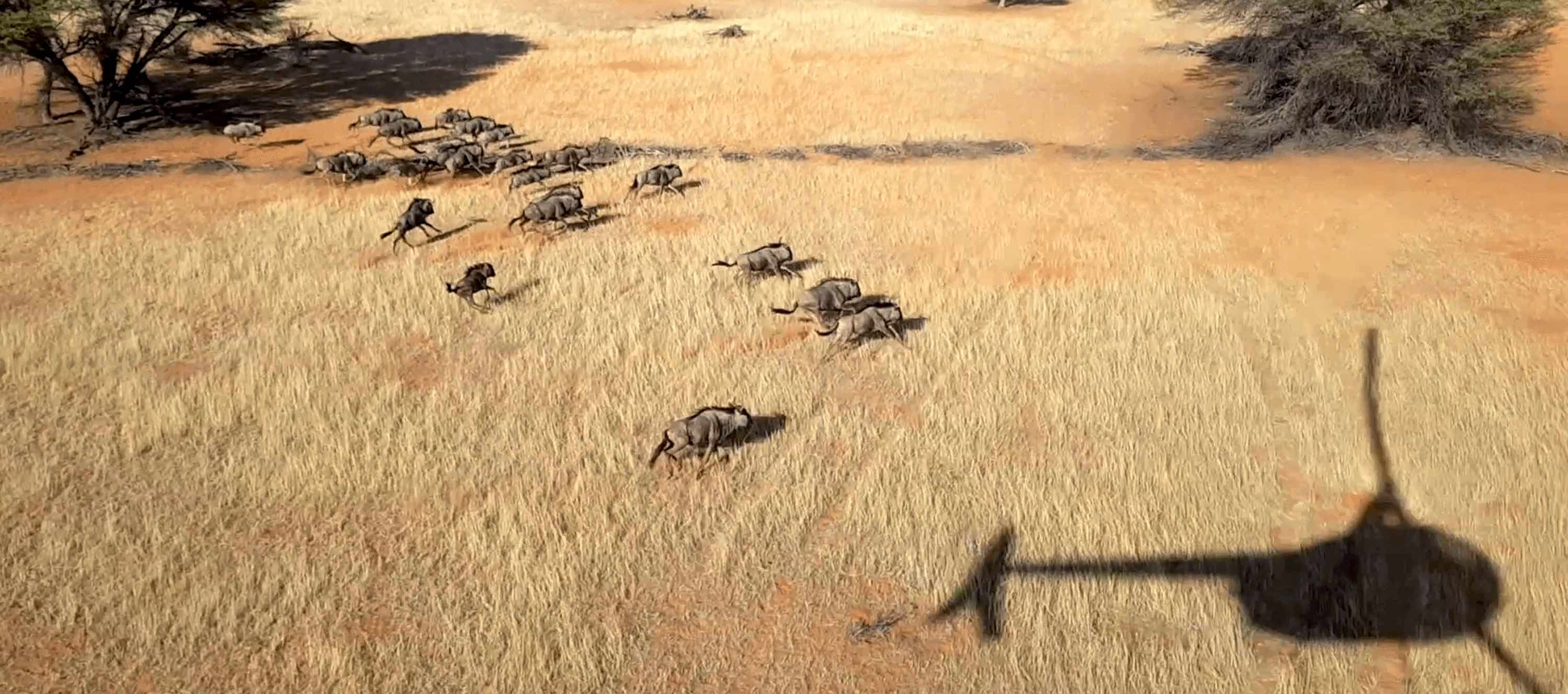

The current regulations require farmers that want to keep wildebeest on their property to erect a double fence. This means that besides the usual game proof fence around the whole property, another fence must be erected 10 metres inside it. Absurdly, these regulations even apply to borders shared with areas that only keep game – e.g. national parks or other private game reserves. To reduce costs, some farmers have created smaller wildebeest camps inside their larger property rather than double fencing the entire farm.

Most Namibian and South African vets agree that this regulation does very little to stop the spread of snotsiekte, given its documented ability to spread over several kilometres. Further, Dr Tubbesing believes that the regulations could actually be creating conditions for the virus to spread. Putting wildebeest in relatively small camps where fights are more frequent and natural herd behaviour is disrupted is likely to result in higher levels of stress and thus more virus shedding.

The entirely ineffective (and possibly counter-productive) fence regulation for wildebeest has much wider impacts than just animal health. Farmers that already have wildebeest on a single-fenced property can now do nothing with them, since the regulations (that were not enforced until recently) prevent them from either culling or selling their wildebeest. Those that don't yet have wildebeest are likely to never buy them.

This means that the price of wildebeest at live auctions is much lower than the real value of this species. Without these regulations, wildebeest are a valuable asset on any game ranch or reserve, as they are popular among hunters and photographic tourists. With these regulations, they become a liability to game ranches and reserves.

Besides the economic issues, extra fencing has terrible environmental impacts. Animals are often trapped and killed while trying to go over or through a fence; doubling fences means doubling the risk of animal deaths on fence lines. Making smaller camps within a larger ranch puts pressure on the habitat, as these areas are likely to be overstocked. Since wildebeest are grazers, high numbers of wildebeest kept in a small camp will cause overgrazing and exacerbate rangeland problems like bush encroachment.

There are no positive aspects of the double fence regulations. Cattle are no safer from contracting snotsiekte and may actually be at more risk due to the smaller wildebeest camps and false sense of security created by the current regulations. Blue wildebeest are indigenous to Namibia, but will occur in ever fewer areas in the country if keeping them comes at an exorbitant cost.

Namibia's wildlife economy, which includes tourism, hunting, meat production and live game sales, already makes a larger contribution to the national economy and job creation than agriculture. With climate change set to make farming crops or livestock ever more challenging, more farmers will want to switch to indigenous wildlife – including wildebeest. These regulations place unnecessary limitations on Namibia's otherwise vibrant wildlife economy and limit its contribution to jobs and revenue, while making no positive difference to agriculture.

Alternative approaches cattle-wildebeest coexistence

In Namibia and South Africa, a number of farmers choose to keep cattle and game on the same property – even grazing on the same land with no fence at all between them. While the risk of disease transmission remains, if both the wildebeest and the cattle are in good health and not stressed, this risk is minimal. Veterinary advice in these cases is to separate them during calving season and at stressful times – e.g. when wildebeest are being captured or culled.

If it is possible to keep cattle and wildebeest on the same property and limit disease transmission between them, then surely it is possible for neighbouring properties to keep them without the need for an extra fence?

If game farmers can keep wildebeest on their property under free-ranging conditions (i.e. not in a camp), there are a number of management options to reduce the risk to neighbouring cattle farmers. Dr Tubbesing suggests maintaining water points and creating good grazing areas (e.g. through de-bushing) in areas of the game ranch that are further from the borders with cattle farms. Game farmers can also inform their neighbours about capture operations and calving seasons to ensure that cattle are in camps further from the game ranch during these riskier times.

Even if these precautions are taken, there remains a small risk that a few cows may contract snotsiekte from wildebeest or sheep. This fear is the main reason why some in the cattle industry want to keep the double fence regulations, even though they don't work. Under the current regulations, a wildebeest owner with a double fence cannot be held responsible for the transmission of snotsiekte to neighbouring cattle farms. Any cattle losses to this disease can only be taken up with the Directorate for enforcing their counter-productive regulations. There are better ways to address these valid concerns from cattle farmers.

Double fencing a mid-sized game ranch of 5000 hectares costs nearly N$ 1 million, so any option cheaper than that would be welcomed by wildebeest owners. Given the low probability of cows contracting snotsiekte in the first place, game farmers could simply offer to compensate any proven case of cattle dying from the wildebeest strain of the virus (i.e. not the one from sheep) on neighbouring properties. Submitting samples from sick or dead cows to the Central Veterinary Lab in Windhoek would confirm or refute the claim beyond doubt, triggering compensation.

Alternatively, all wildebeest owners could be charged a nominal ‘disease insurance' payment to a central fund that would be used to pay out any proven cases of cattle dying from wildebeest snotsiekte. This insurance premium would be much cheaper for game farmers than double fencing (a few thousand N$ rather than a million) while providing a safety net for affected cattle farmers.

A reliable and effective cattle vaccine has already been developed abroad and should soon be produced in South Africa, which will resolve this problem once it is rolled out there and in Namibia. This would eliminate the need for any kind of compensation, as cattle owners could simply vaccinate their animals. Until that time, the double fencing regulations should be replaced with practical ways of preventing the viral spread along with compensation for the few cases that still occur. This more pragmatic approach will benefit the Namibian economy at no risk to the agricultural sector.

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.