Namibia's elephant population has been the subject of some debate recently, with some claiming that there are far fewer of these pachyderms in the country than official statistics suggest. While some objections to the official numbers constituted flat-out science denial, others suggested that the Namibian counts were overestimates due to the trans-boundary nature of the country’s largest elephant sub-population. This valid concern was put to bed with the recent publication of a synchronised regional elephant survey that accounted for elephant border crossings.

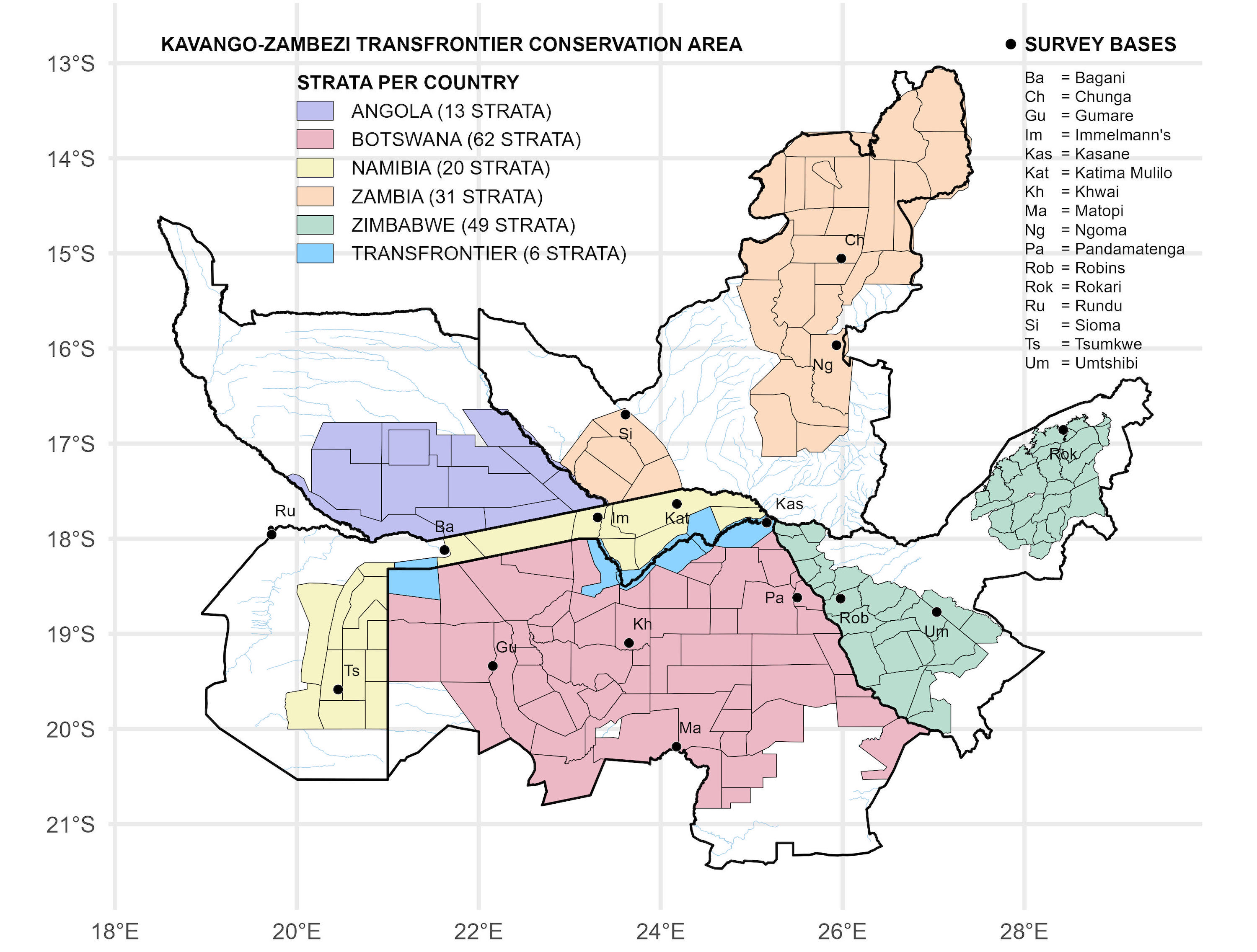

Most of Namibia's elephants occur in the wetter northeastern part of the country including the narrow Zambezi Region (former Caprivi Strip) that fits snugly between Angola, Botswana and Zambia, and just touches Zimbabwe on its eastern tip. This strip of land is a key ecological link among these countries that, along with Namibia, contribute to the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA TFCA).

For the first time in history, six trans-boundary counting blocks (known as strata) were established between Namibia and Botswana close to their shared rivers (see Map). Since the count was done in the late dry season when elephant movements are limited by water availability, any major trans-boundary movements were expected close to the rivers. While the trans-boundary strata were counted as though they were in the same country, the data were separated according to country during analysis. This strategy was complemented by conducting all counts in adjacent strata within as short a timespan as possible, thus limiting counting errors due to elephants moving between one stratum and another.

The second largest elephant population in Namibia – in Khaudum National Park and neighbouring Nyae Nyae Conservancy – is also part of the KAZA TFCA and borders with Botswana. However, there are far fewer cross-border elephant movements in this area due to the lack of permanent water sources on either side of the border. Adding the two sub-populations in northeastern Namibia together gives us an estimate of how many elephants occur in Namibia’s portion of the KAZA TFCA.

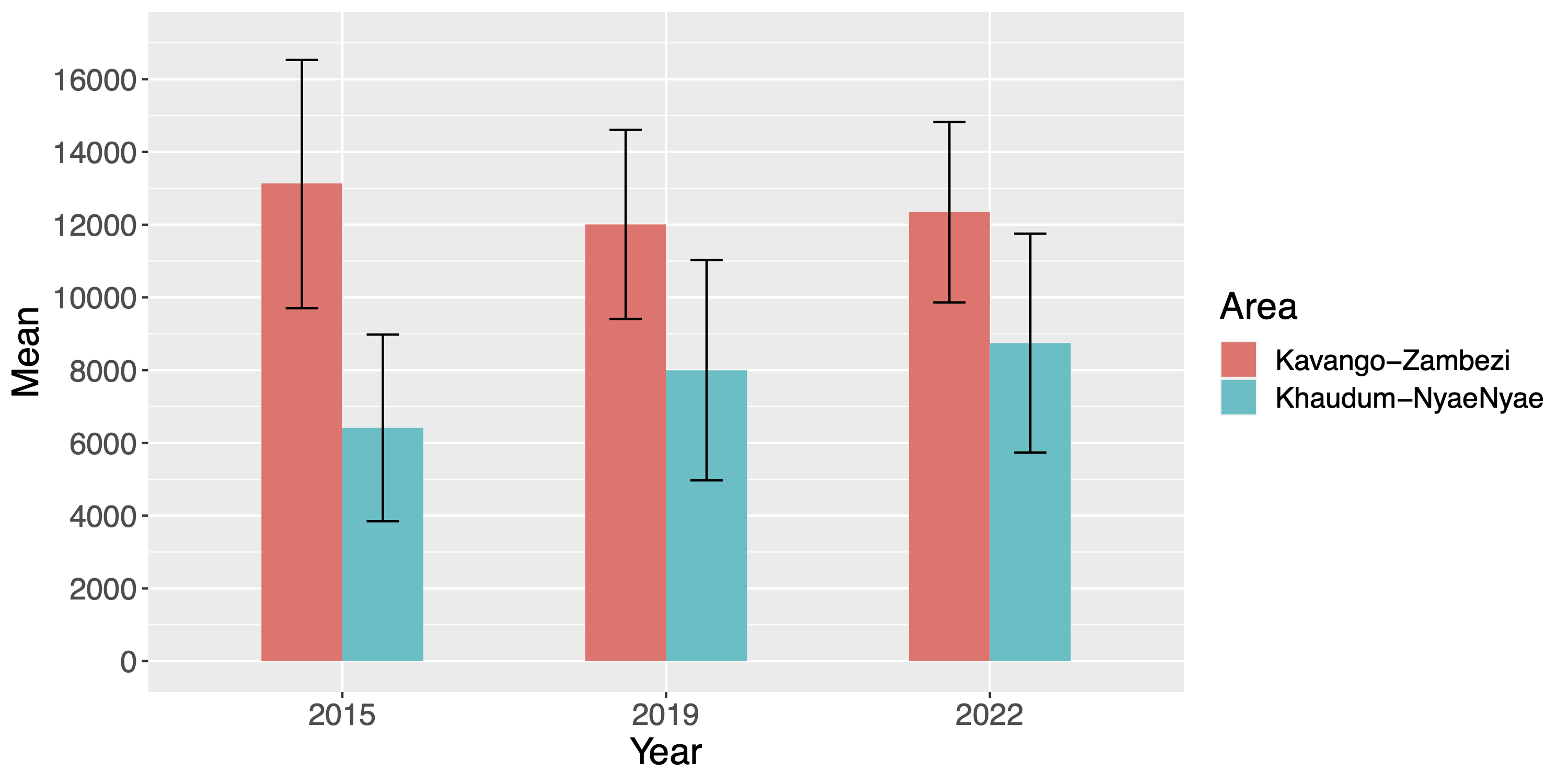

The 2022 KAZA aerial survey produced an estimate of 21,090 ± 3,888, which is not far off the Namibian estimates for 2019 (20,007) and 2015 (19,549). The estimates for the Zambezi-Kavango portion of Namibia have remained stable since 2015, while the estimates for the Khaudum-Nyae Nyae portion are increasing slightly (see chart below). The long-term health of the population was further confirmed by the low ratio of elephant carcasses vs. live elephants in Namibia, at only 3.57% (over 8% is considered high).

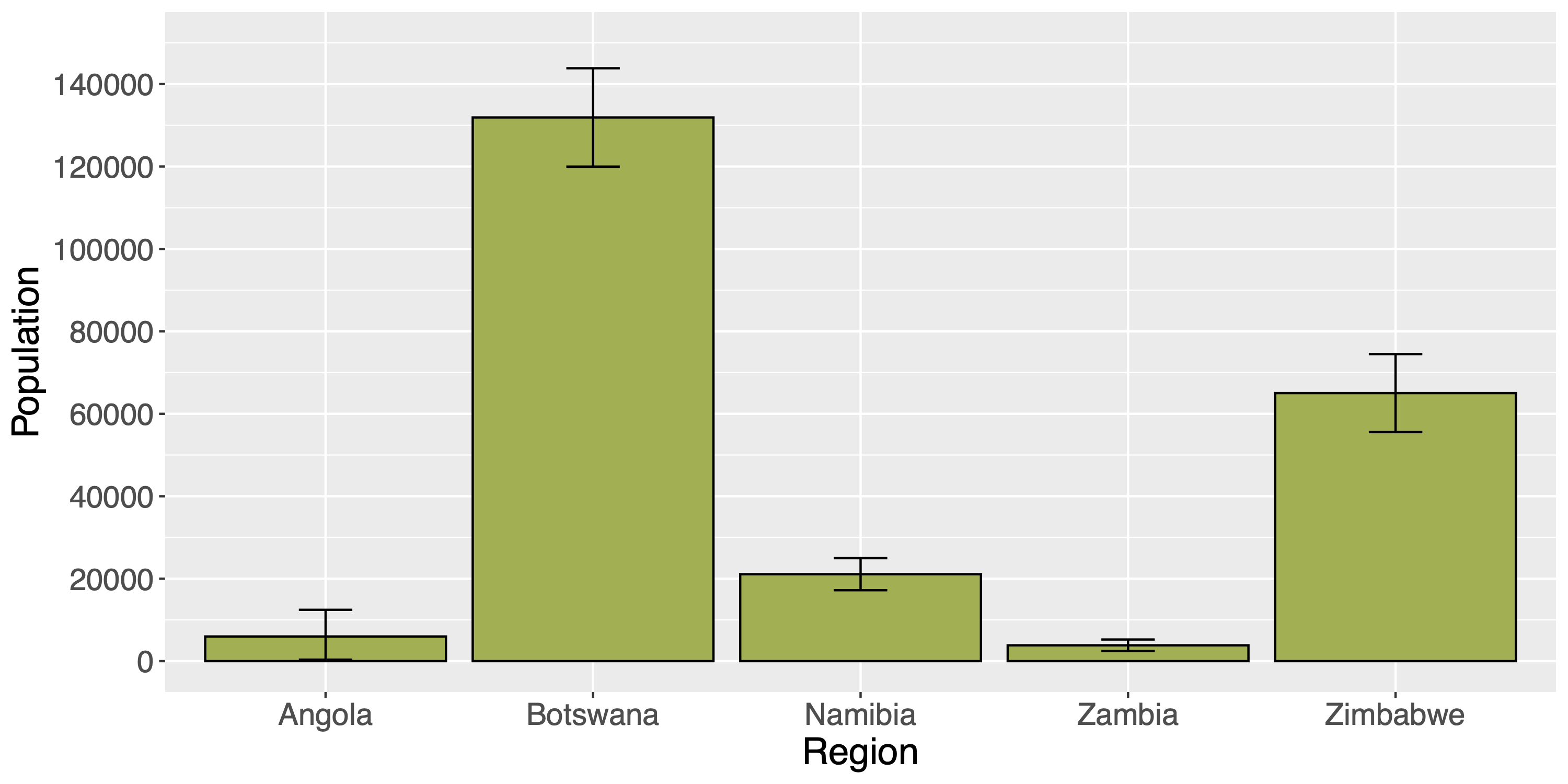

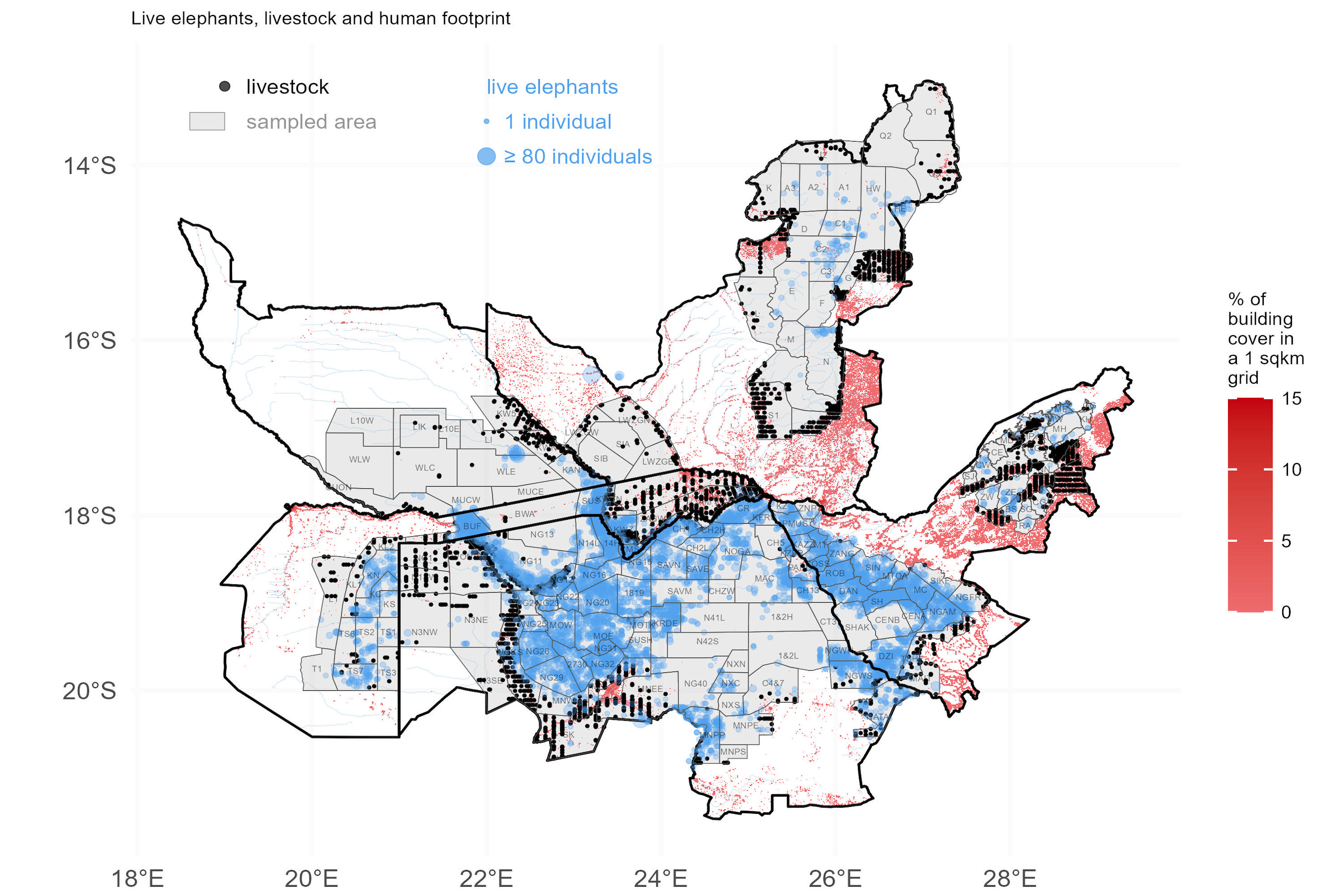

These results reveal that the elephant population is healthy and stable. Since Namibia hosts 9% of the total KAZA population and KAZA hosts half of Africa’s savannah elephant population, this is good news at a significant scale. The main challenge for Namibia at this stage is to manage human-elephant conflict, particularly where the elephants overlap with villages and crop fields.

The eastern part of the Zambezi Region is among the most densely populated areas covered by the KAZA aerial survey (the survey covered 60% of the whole KAZA TFCA; areas where few or no elephants were expected were not surveyed). High human densities were recorded close to the rivers where most of the elephants occur, which unsurprisingly leads to high levels of human-elephant conflict. The communal conservancies in the Zambezi Region thus play a critical role in reducing the conflict and finding ways for humans and elephants to coexist.

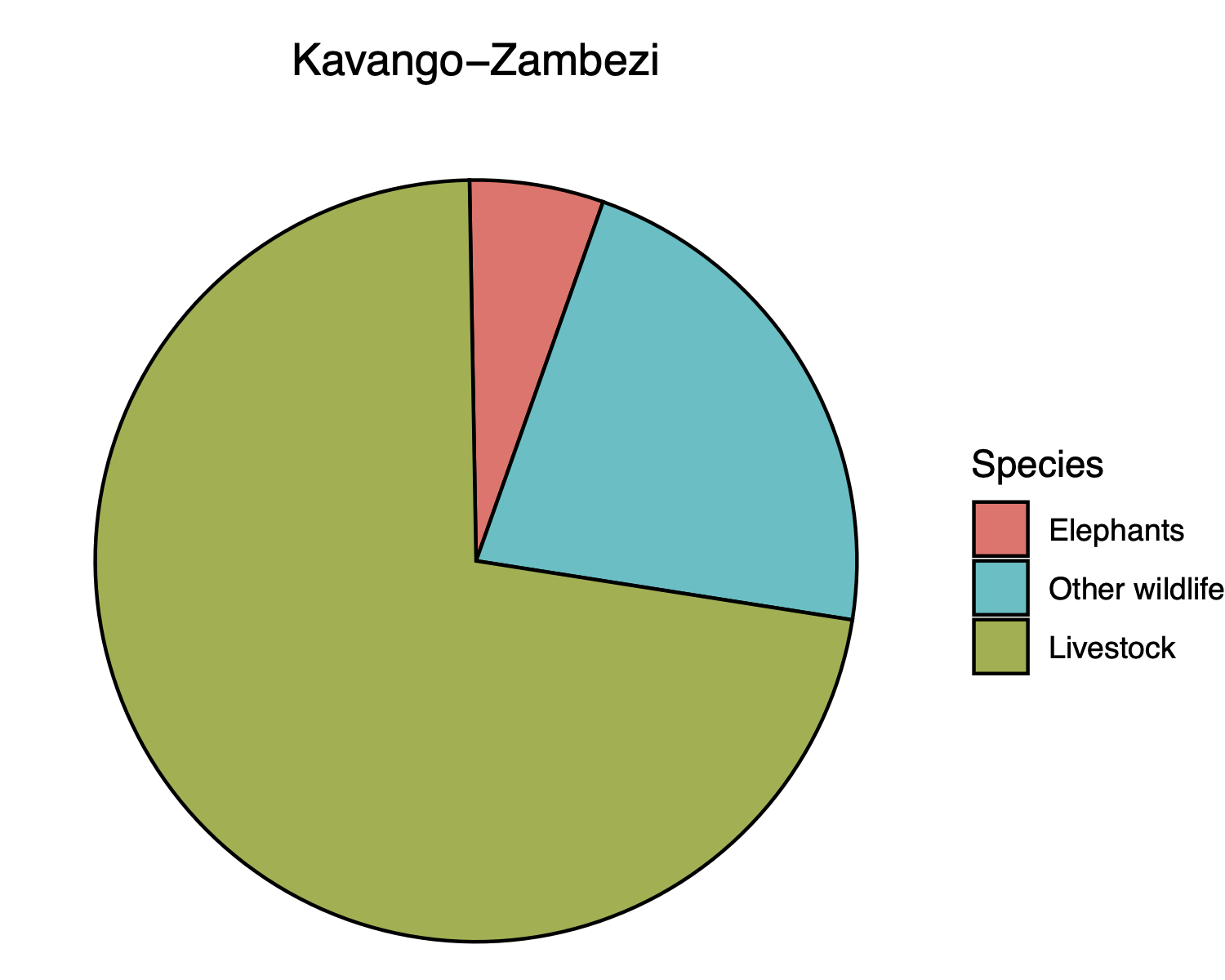

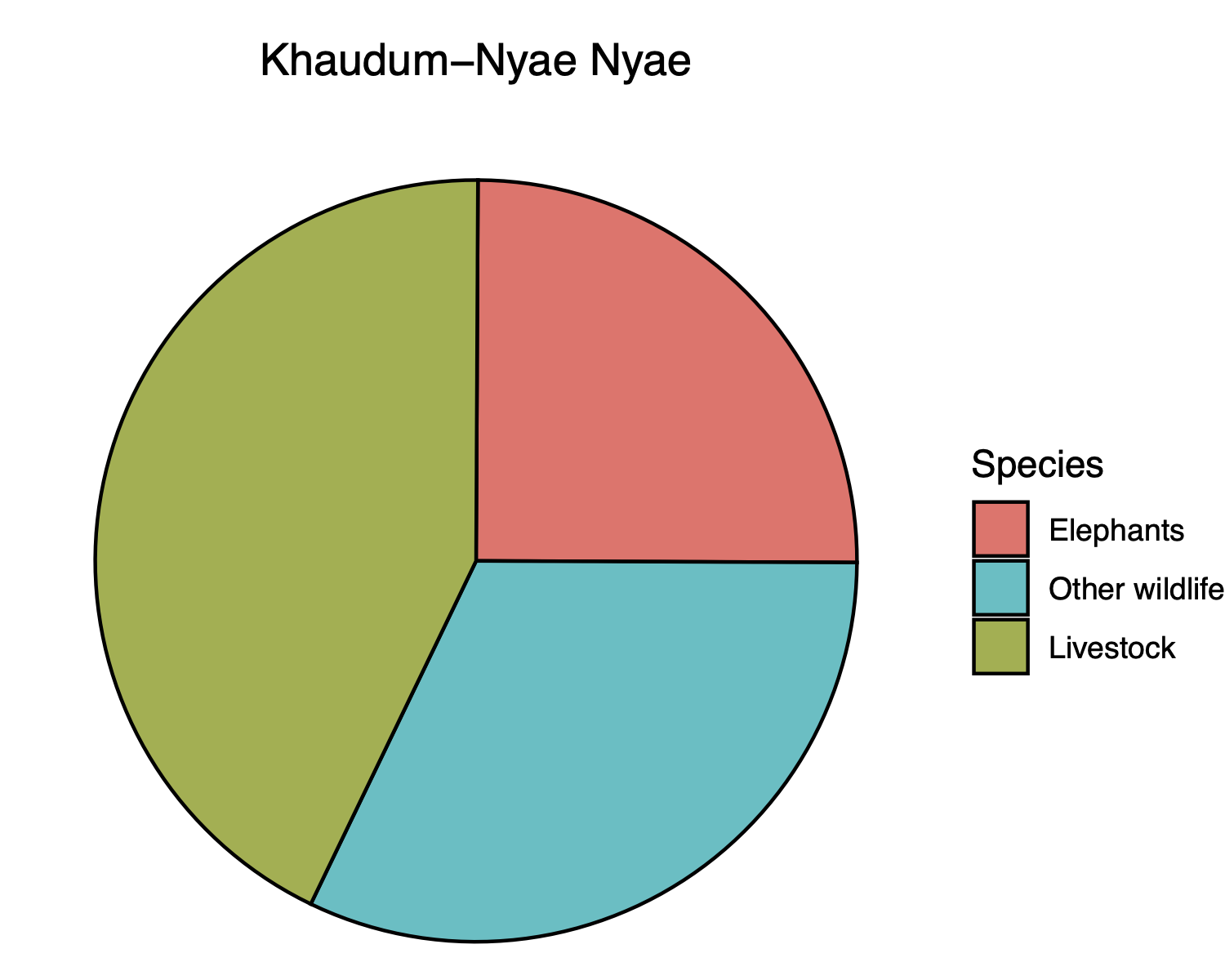

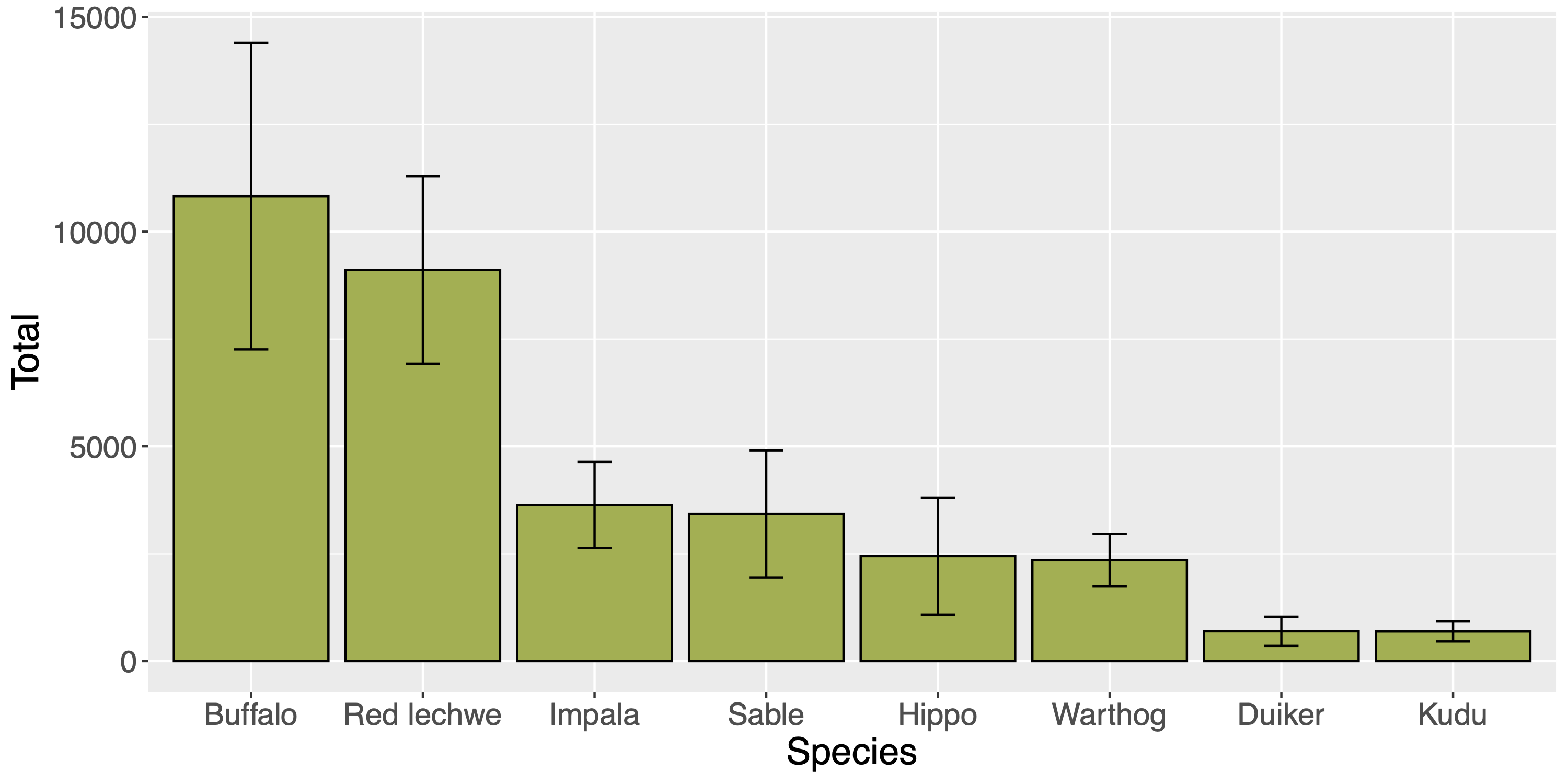

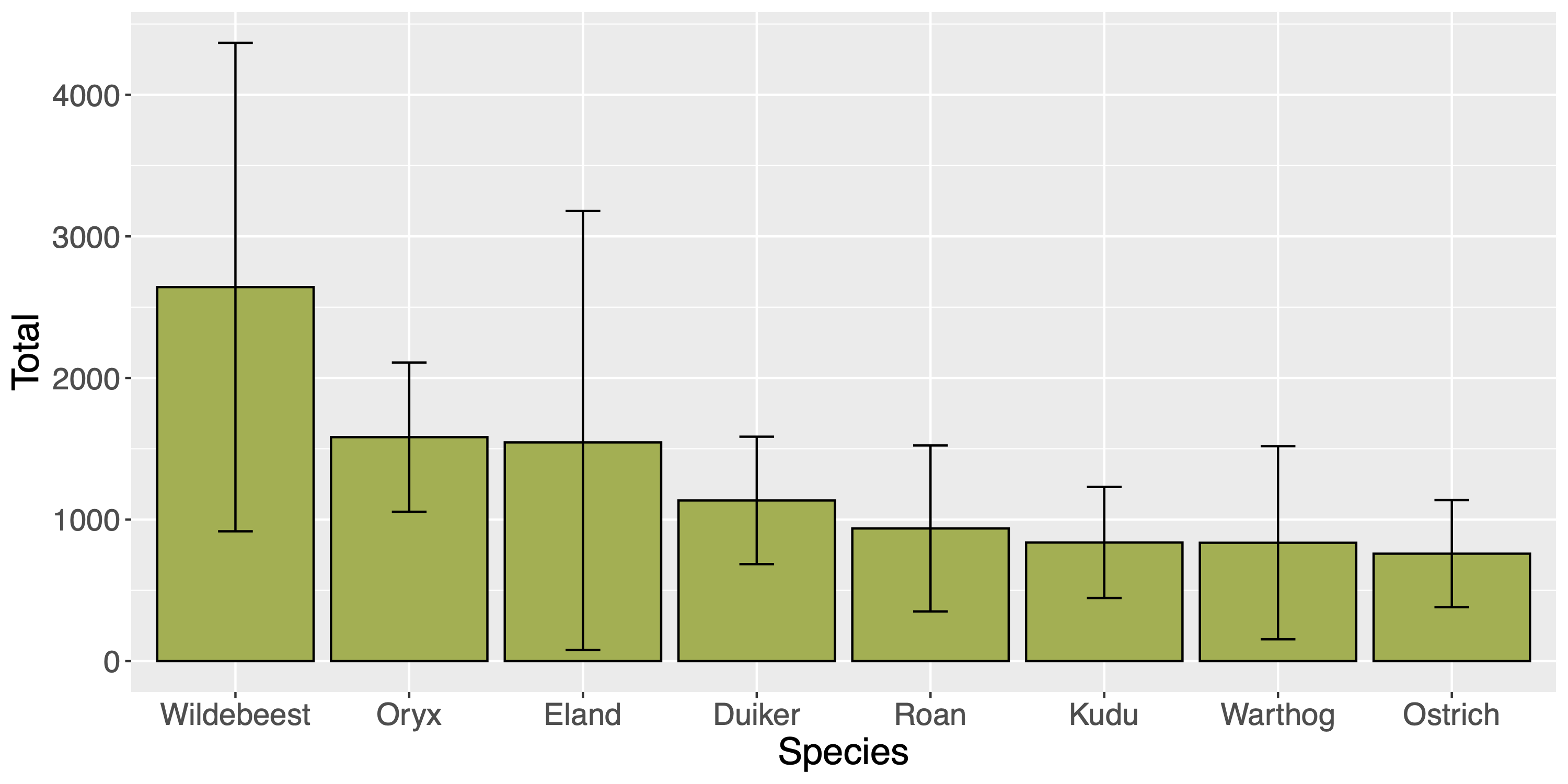

Although this was an elephant survey, the survey teams made use of their time in the air to count other wildlife species and livestock. The survey was designed to match survey intensity with expected elephant density, so the estimated numbers of the other animals are likely to be less precise than the elephant numbers. Even where relatively precise estimates are achieved (indicated by narrow error margins), they can be inaccurate for species that are unevenly distributed across the landscape (e.g. hippos) or difficult to spot from the air (e.g. kudu). Nonetheless, the other wildlife sighting data provide ballpark estimates and species distributions, which can be used as a starting point for studies that focus on those animals. The inclusion of livestock numbers also provides an interesting comparison with elephant and other wildlife numbers.

Conducting an aerial survey over five different countries in a relatively short timespan was a mammoth task. The survey itself is thus a celebration of the KAZA TFCA as a means of bringing countries together to achieve a common purpose for conservation. The final report, including full transparency on the survey’s limitations, is a world-class product that can be used as a guideline for future surveys in KAZA and similar elephant surveys elsewhere in Africa. The KAZA countries are rightly proud of this achievement that further confirms their place as world-leaders in elephant conservation.

Bussière, E.M.S. and Potgieter, D. (2023) KAZA Elephant Survey 2022, Volume I: Results and Technical Report, KAZA TFCA Secretariat, Kasane, Botswana. https://www.kavangozambezi.org/kaza-elephant-survey/

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.