Namibia's community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) system links the sustainable use of natural resources with wildlife conservation and sustainable development. Since CBNRM was established, wildlife populations on communal lands outside protected areas have increased. However, rising wildlife numbers also naturally intensify the number of interactions people have with wild animals, some of which result in negative impacts on both people and wildlife. Managing this problem is a key challenge for the CBNRM programme.

In our recent study, we explored the patterns and potential drivers of livestock depredation, crop raiding, infrastructure damage and attacks on humans – which are the four types of human-wildlife conflict recorded through the Event Book system in Namibia. Our main goals were to 1) map human-wildlife conflict incidents reported across the country, and 2) find out if there were times of year when numbers of reports were highest. Answering these questions helps us to determine what drives human-wildlife conflict. In other words, does the place or season make a difference to the level of impact that wildlife has on people's lives and livelihoods? Understanding these patterns could ultimately aid collective efforts to reduce human-wildlife conflict in areas where it is most prevalent so as to protect rural communities' livelihoods and increase tolerance towards wildlife.

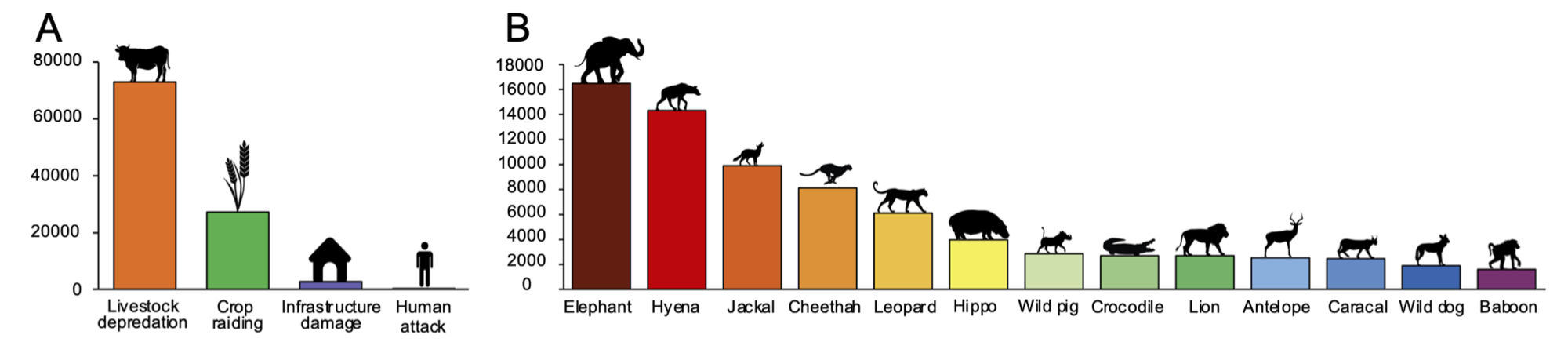

During 2001–2019, people in 79 communal conservancies throughout Namibia reported 112,165 human-wildlife conflict incidents (averaging 5,903 reports per year), while 1,415 ‘problem animals' were killed or trapped (average of 75 per year). The most common types of incidents reported at a national level was livestock depredation (83%), followed by crop raiding (15%), damage to infrastructure (2%) and human attacks (<1%). Elephants reportedly cause most of the damages (22%), followed by hyenas (spotted and brown; 19%), jackals (13%), cheetahs (10%) and leopards (8%).

Interestingly, although lions caused only 4% of total incidents reported, they were the top species declared as ‘problem animals' by the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT). This mismatch could be the result of related, but different issues. Perhaps, people fear lions more and therefore want them removed, or the species sometimes causes higher value losses than others (e.g., adult cattle or entire goat herds), but low tolerance levels could be due to other factors.

The type and severity of impacts varied across Namibian communal conservancies, with the highest number of reports in the Kunene (55%) and Zambezi (22%) regions. The three species reported most often in the Kunene region were hyena (25%), cheetah (22%) and jackal (15%), compared to elephant (40%), hippopotamus (15%) and wild pigs (warthog and bush pig; 10%) in the Zambezi. However, the highest mean number of livestock losses per inhabitant was in the South, where smaller predators such as jackal and caracal prey on the extensively farmed small stock. Crop raiding was highest in the north-eastern regions, where higher mean annual rainfall and more productive soils allow for greater crop production. Infrastructure damage was most frequent in the arid north-western and north-central regions, where conservancies rely heavily on ground water sources and associated infrastructure. These water sources within an otherwise arid environment are a major attractant to wildlife, which could then break pipes, windmills or reservoirs when trying to drink.

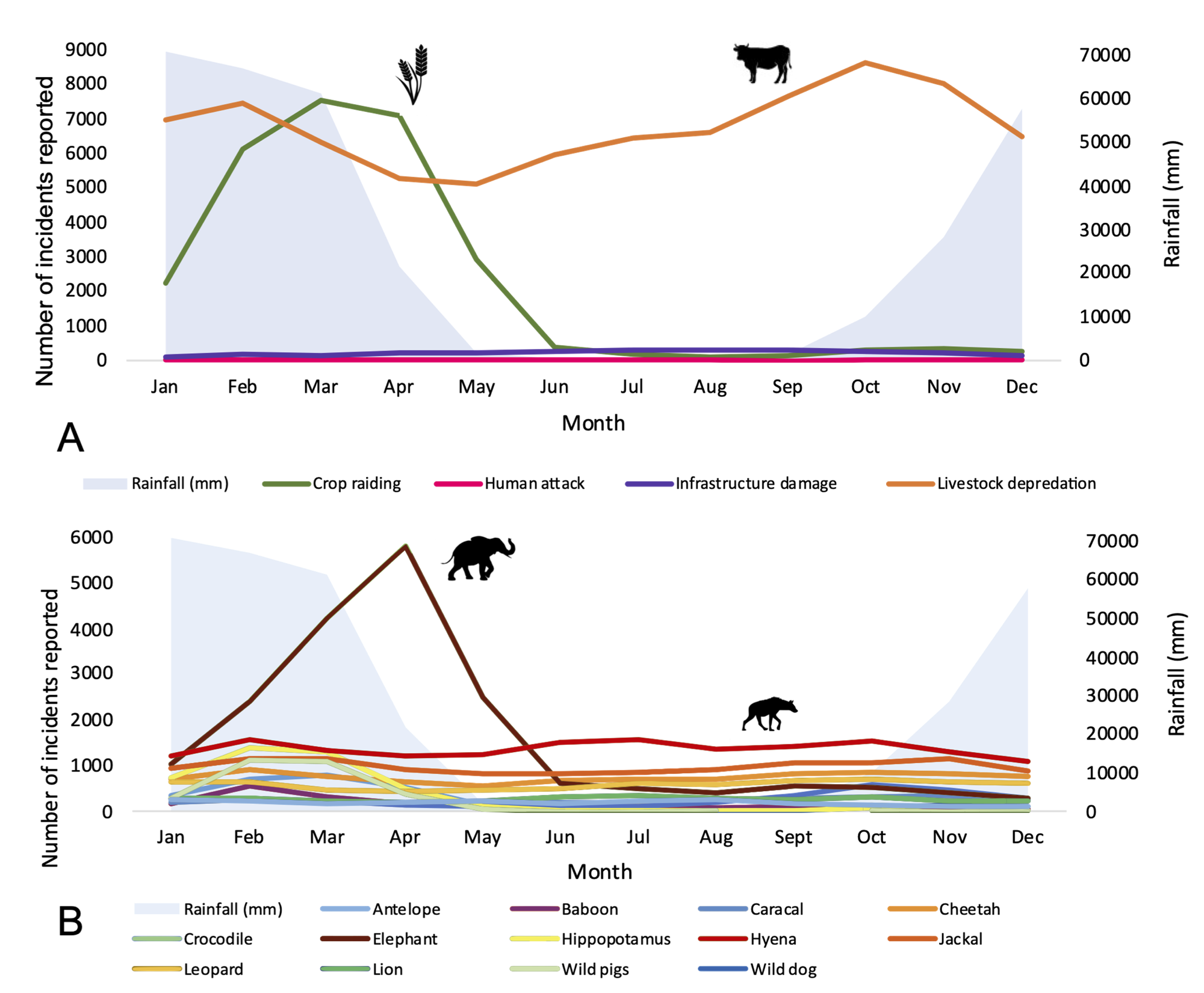

Studies from many parts of the world have found that human-wildlife conflict levels vary seasonally in areas with defined dry and wet periods. In Namibia, livestock depredation is exacerbated at the end of prolonged droughts with the onset of the first rains of the wet season (October/November). During this period livestock are in poor condition and wild prey species will move to areas where rain has fallen, leaving local livestock more vulnerable due to lack of prey for resident predators. Meanwhile, crop damages peaked in the late wet season (February to April) when the crops were ready for harvest and therefore most tempting to wildlife. The number of infrastructure damage reports increased with low monthly rainfall, most likely linked to wildlife damage of water infrastructure rather than kraal and traditional crop field fence damages. We found an apparent lack of seasonality in attacks on humans, most likely because too few attacks occur (one or two per year) to detect trends, but it is possible that attacks stem from chance encounters and that most conservancy members are careful not to take unnecessary risks.

When looking at spatial patterns, crop raiding was higher closer to protected areas, which provide refuge for wildlife moving into the neighbouring conservancies, and perennial rivers that are key sources of water. The rivers also form natural boundaries with neighbouring countries such as those in the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA). None of the environmental or human-related predictors for livestock depredation that we looked at were statistically significant, which could be because impacts are so widespread across such diverse landscapes, species, and farming systems, that no single variable or set of variables can explain hotspots of livestock losses at a national level. However, human-carnivore conflict has been largely attributed to increasing human and predator populations, as well as fluctuating game populations due to recurring droughts.

Spatial patterns in human-wildlife conflict were also found when looking at data from specific wildlife species. Livestock losses due to hyenas and leopard were more prevalent closer to protected areas. It is possible that these predators use protected areas as a refuge, which they occasionally leave to prey upon livestock on neighbouring lands, while other species may be more resident outside protected areas. Terrain ruggedness seemed to increase incidents with cheetah and leopard, but decrease incidents with elephant. Ruggedness provides carnivores with places to rest or hide, habitat diversity, water availability, stalking opportunities, and protection from people. Elephant densities are higher in the flatter north-eastern regions where crop production is higher, compared to the rugged north-western regions where elephant are mostly responsible for infrastructure damage.

Leopard and cheetah reports have increased since the implementation of the human-wildlife self reliance scheme, while elephant reports have dropped—this could simply be due to an overall increase or decline in incidents or could indicate that (even if modest) the monetary offset for livestock losses could be encouraging farmers to report some species and not others. Cheetah, leopard, and hyena incidents were more commonly reported in arid areas where natural prey numbers fluctuate with droughts. Hyenas caused more losses in areas that had higher densities of livestock. Interestingly, none of our chosen predictors were significantly linked to reported lion incidents.

Our results are similar to findings in Kenya and Botswana, suggesting that Namibia is dealing with similar challenges to other African countries. In particular, our study aligns largely with recent research, which highlighted that more crop damage may occur near rivers and wildlife corridors, while higher livestock density is related to more livestock losses in driving spatial impacts of wildlife (applying to hyenas only in our study).

Studies like ours that look at many species can guide management decisions and mitigation efforts that are both economically and physically feasible, and promote collaboration among local stakeholders, conservation groups and government. We showed the extent of negative impacts wildlife may have on people and their livelihoods in Namibia, and how this varies both spatially and temporally across the country. Namibia continues to work towards better coexistence between people and wildlife by reducing the severity of impacts wherever possible. Monitoring trends and detecting spatial patterns is a starting point for developing affordable, practical solutions that will benefit people and wildlife.

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.