What is a communal conservancy?

A Namibian communal conservancy is a community-based institution that has obtained conditional rights to use the wildlife occurring within a self-defined area. They are self-governed, democratic entities managed by committees that are elected by their members.

To establish a conservancy, an elected committee must meet all the requirements given by the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) in the 1996 amendment of the 1975 Nature Conservation Ordinance. Once these requirements are met, the Minister will declare the new conservancy in the Government Gazette. Although MEFT does not govern conservancies, it may de-register any conservancy not complying with conservation regulations. To date, 86 conservancies have been gazetted.

The MEFT requirements include a verifiable list of community members, a constitution outlining governance rules agreed by the community and a map of the area (charted upon agreement with neighbours) to be managed as their conservancy. The governance rules include a benefit distribution plan, game management plan and rules regarding community meetings, committee elections and financial management.

How do communal conservancies work?

Each conservancy is ultimately governed by its own constitution, but there are many similarities among them. A committee comprising local community members are elected to the positions of Chairperson, Secretary and Treasurer, with a Vice selected for each position. Some conservancies elect additional committee members to these six positions and most allocate an ex officio position for a local Traditional Authority.

The committee makes decisions and provides guidance for permanent conservancy staff members, which include a manager, office administrators (for some conservancies) and game guards. The staff members are responsible for day-to-day management and report to the committee, which in turn reports to the broader membership at community meetings. Each conservancy should hold one Annual General Meeting (AGM) per year and usually other General Meetings and/or smaller village-level meetings held to discuss specific issues.

Conservancy members elect or re-elect their committee members at a special AGM every few years – the frequency of elections and limits to committee term lengths depends on the conservancy constitution.

How do communal conservancies generate income?

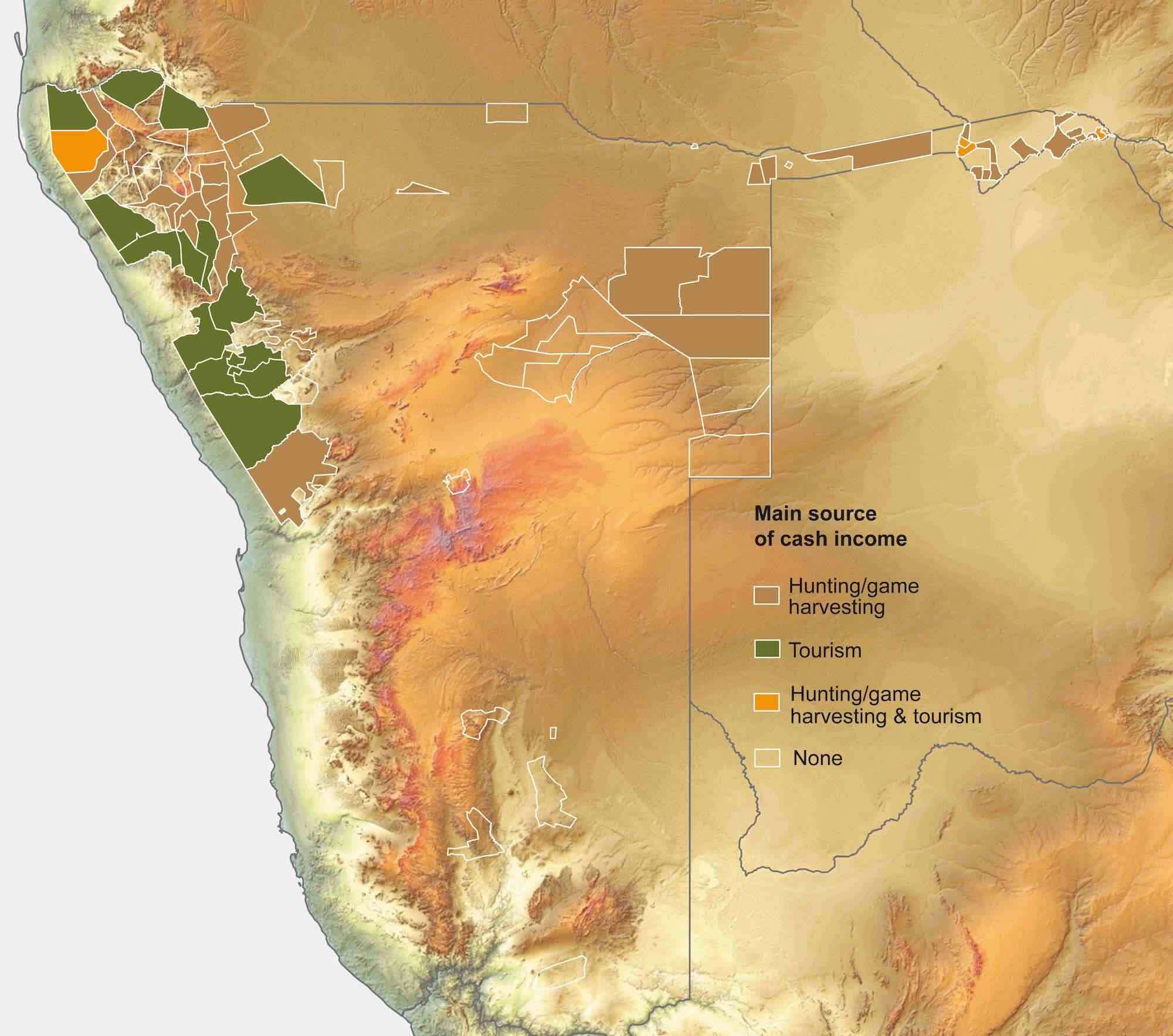

The two main income streams for communal conservancies are photographic and hunting tourism. Sales of indigenous plant products and handicrafts also provide some income for harvesters and crafts producers working in conservancies. Conservancies will ordinarily sign joint-venture agreements with private lodge and/or hunting operators after negotiations regarding revenue sharing, employment creation and other details. A few conservancies own lodges and contract the management out to private companies.

There are currently 54 joint-venture lodge agreements and 56 conservation-hunting agreements on communal conservancies. Not all conservancies are suited to photographic tourism and some new conservancies do not have enough wildlife yet to sign hunting agreements. Consequently, only 69 of the 86 conservancies generated returns in 2017 and 39 were able to cover their own operating costs.

A total of N$ 132,824,233 of returns and benefits (including the value of harvested meat) was generated in the conservancy programme in 2017. The income generated by communal conservancies has grown each year since the first conservancies were registered in 1998.

How do communal conservancies conserve wildlife?

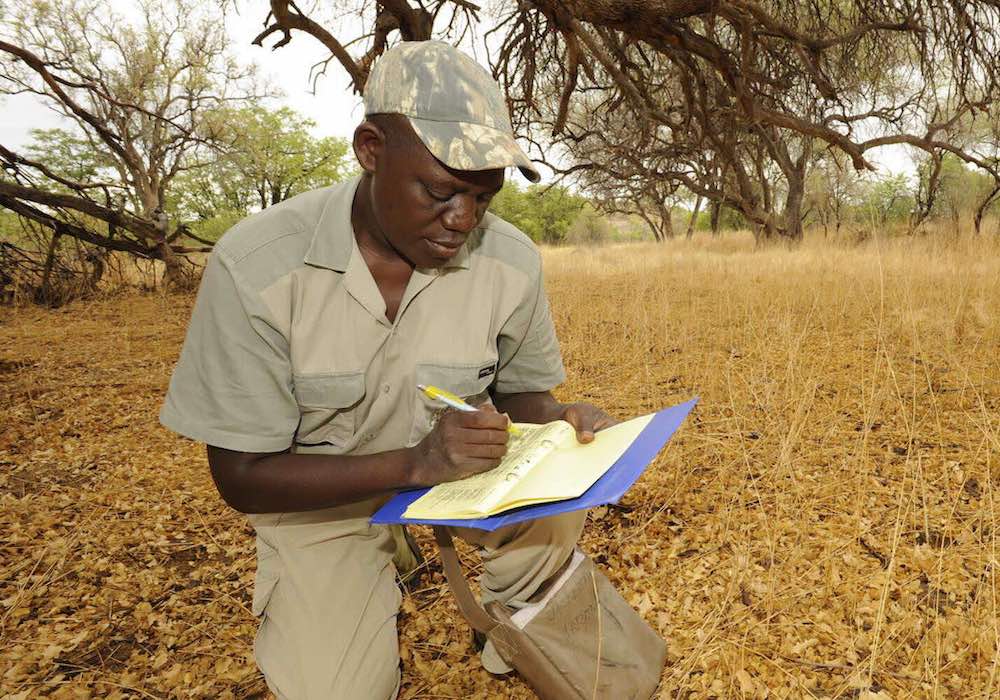

Each conservancy employs conservancy game guards, who are tasked with monitoring their wildlife and reporting on any wildlife-related incidents like human-wildlife conflict, poaching incidents and sightings of rare wildlife species in an Event Book. The Event Book system links on-the-ground monitoring in individual conservancies with larger-scale monitoring that can show trends over time or over larger areas by combining data from several conservancies. In some conservancies, people are employed to monitor natural resources like plants and fish that are important for livelihoods in these particular areas.

These day-to-day records are supplemented by annual game counts (by road or foot) where game guards join MEFT and non-governmental support teams to count wildlife on selected routes through the conservancies. The game guards also help MEFT and other anti-poaching teams by alerting them to suspicious activity in the conservancy areas. Finally, they accompany hunters to record how many animals are taken in each hunt, which is critical for monitoring this activity. This monitoring information informs management decisions regarding wildlife off-take quotas and highlights the need for further interventions – e.g. anti-poaching or human-wildlife conflict mitigation.

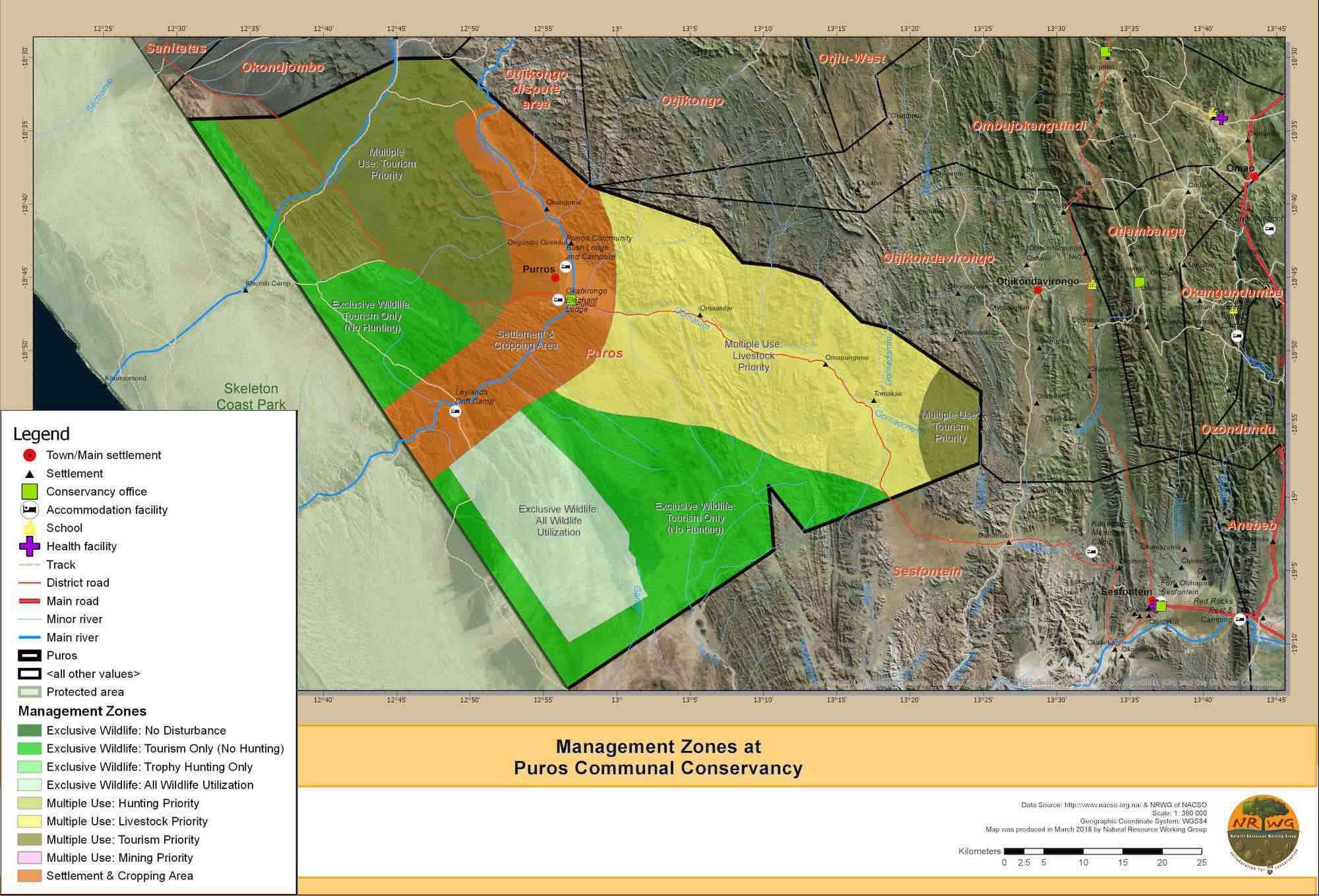

Each conservancy has a land use management plan, whereby they demarcate areas to be reserved for wildlife only and areas that are used for other purposes (e.g. farming). The conservancy system provides a mechanism for addressing human-wildlife conflict, as they work with MEFT and non-governmental organisations to help farmers that suffer losses to wildlife and implement mitigation methods – e.g. predator-proof kraals and elephant-proof water points.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more information, see the

State of Conservancies report,

Keeping Namibia's Wildlife on the Land brochure or visit the

Keeping Namibia's Wildlife on the Land website.

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.