Using Stripe Patterns to Monitor Hartmann’s Mountain Zebra in Namibia

By Prof L. M. Gosling

9th August 2019

The Mountain Zebra Project aims to understand what causes changes in Hartmann’s mountain zebra population size in order to provide information needed for their conservation. This sub-species is classified as Vulnerable under the IUCN Red List and is specially protected in Namibia [1]. Historical records show that they are vulnerable to extreme drought, particularly when fencing restricts their ability to find remaining patches of grazing.

In this project I use two zebra characteristics to monitor their populations: 1) each mountain zebra can be recognised using fingerprint-like variation in stripe patterns and 2) they need to visit waterholes to drink. Using motion-sensitive camera traps at waterholes, I have photographed and identified large numbers of zebra in some key populations. For example, over 3,000 individuals are now known in the mountainous part of the Namib-Naukluft National Park.

When I identify animals under two years old, I estimate their year of birth and then follow their progress throughout the rest of their lives using networks of camera traps. Individuals that are not seen for several years are assumed dead. Births and deaths in the population are then related to factors in their environment such as rainfall and consequent grass growth, and zebra population density. Rainfall is the main predictor of zebra birth and death rates in Gondwana Canyon Park in southern Namibia – in good rainfall years, there are more births and fewer deaths, and vice versa in years of drought.

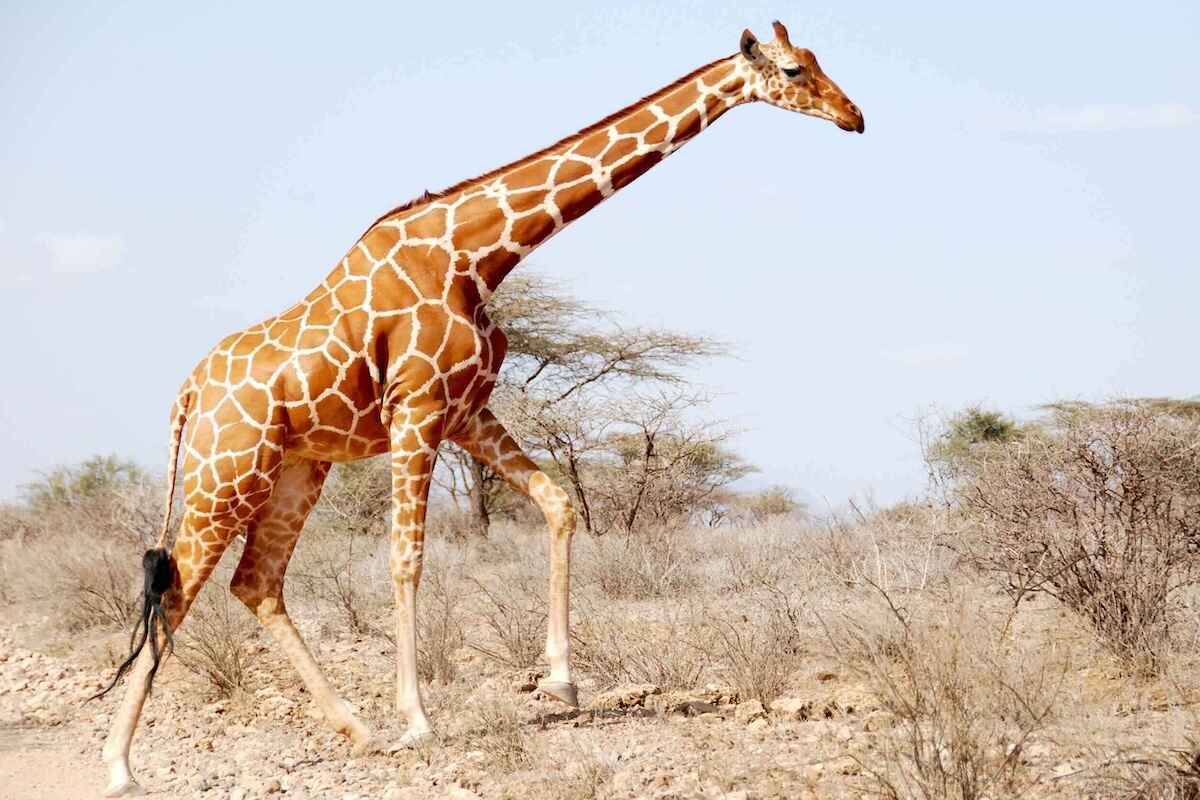

Hartmann’s mountain zebra have unique stripe patterns that allow researchers to identify them individually

The study started in Gondwana Canyon Park in 2005 but, as I am interested in knowing how much rainfall or predation affects Hartmann’s mountain zebra throughout Namibia, I have extended my study to sites that have more rain and more predator species than this protected area in the arid south. Two of these sites – Etosha National Park and the Hobatere Concession Area – have a full array of large predators. While in the Namib-Naukluft National Park and NamibRand Nature Reserve, only lions and African wild dogs are absent, Gondwana Canyon Park and Ai-Ais National Park host very few hyenas, and no lions or wild dogs, which makes it an ideal study site with little or no predation on zebra. Leopards and cheetahs are present in all six sites, but they probably have only a minor role as predators of mountain zebra. We do not yet know what role predation plays in limiting mountain zebra populations, so a comparison of these sites will contribute to our understanding of this crucial aspect of their biology.

While an understanding of key population processes, like birth and death rates, is ultimately most important for conservation management, landowners and managers also need to know how many animals are in their areas. Zebras are usually counted by driving specific roads at given times of the year, which is a standard method for counting herbivores. These road counts provide important information on population trends, but probably underestimate mountain zebra populations.

It is difficult to count this species in its mountainous habitat, as zebra can be extremely wary of vehicles, especially in areas where they have been hunted. Even aerial surveys can underestimate mountain zebra populations, as they may seek shade by standing under rocky overhangs and thus escape detection from the air. Individual-based monitoring by the Mountain Zebra Project using camera traps potentially provides the information needed to supplement and correct these estimates.

Hartmann’s mountain zebra survive in arid, mountainous areas like Gondwana Canyon Park by moving long distances in search of grazing.

My research supports the contention that Hartmann’s mountain zebra rely on free movement over large areas for their long-term survival. While their population is currently quite healthy, we know that a large proportion of the national mountain zebra population died in the severe drought of the 1980s. The ultimate reason for this mass mortality was lack of food due to low rainfall, but fences erected around farms magnified the problem by restricting the zebras’ movement. Mountain zebra depend on moving to patches of grass that grow after highly localised rainfall in their arid environment.

Under drought conditions the zebras’ ability to move to patches of remaining vegetation is vital to their survival. This problem can be addressed by landscape scale conservation initiatives that encourage fence removal. Initiatives that provide most grounds for optimism are the communal conservancies in the northwest of Namibia, and the NAM-PLACE scheme that aims to link up protected areas, conservancies and neighbouring lands.

Using my networks of cameras I have frequently recorded individual zebras walking over 40 km in response to patchy rainfall in the Greater Sossusvlei-Namib (5,730 km2) and Greater Fish River Canyon (7,621 km2) landscapes. Hopefully the sheer size of these areas will help buffer the mountain zebra from drought, and thereby reduce the mass mortalities experienced in the past.

References:

1. Gosling, L.M. et al. (2019) "Equus zebra ssp. hartmannae." The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T7958A45171819.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T7958A45171819.en

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.