Conversations in the Cacophony

How Cape Fur Seals Communicate Within their Massive Breeding Colony

9th September 2021

A visit to the Cape fur seal breeding colony at Cape Cross on the Skeleton Coast of Namibia will leave you with two distinct impressions: the fishy smell and the constant noise. The barking, growling and bleating of 210,000 seals sounds like chaos to the human ear, which leaves us wondering: how do mother seals find their pups, or male seals differentiate between mates and rivals in this apparently confusing cacophony?

Seals, sea lions and walruses (collectively known as pinnipeds) are a particularly interesting group of mammals in terms of communications, as they are highly vocal, live in colonies of varying densities and have a variety of mating strategies. The Cape Cross colony of Cape fur seals provides an excellent case study for investigating pinniped communications; this is the densest colony of pinnipeds in the world, which requires the seals living here to have clear communication strategies. Surprisingly, while communication among several other pinniped species has been studied, we know nothing about Cape fur seal communication. The Namibian Dolphin Project therefore teamed up with French researchers from Paris-Saclay University to investigate. Although this project is not yet finished, we have already uncovered some of the seals' strategies for communicating clearly despite the deafening din.

Navigating social life in a seal colony is a complicated business, as seals of different ages, sexes and social statuses all congregate on a small strip of beach. Without clear communication, a pup would lose its mother and starve, or a subadult male would stumble into a dangerously territorial adult male – knowing who you are talking to in the colony is a matter of life and death.

Cape fur seal breeding colonies are organised in harems: mature males (bulls) establish territories that encompass 10 to 30 females and their pups. Bulls spend the entire breeding season from late October to early January defending their territory and harem, with no time to go to sea and hunt for their dinner. Females give birth to a single pup in November or early December and nurse it for 10-11 months. During this time, they spend alternate periods on land to nurse their pups and at sea to forage for food. Every time they return to the colony, each mother must find her young among thousands of other pups.

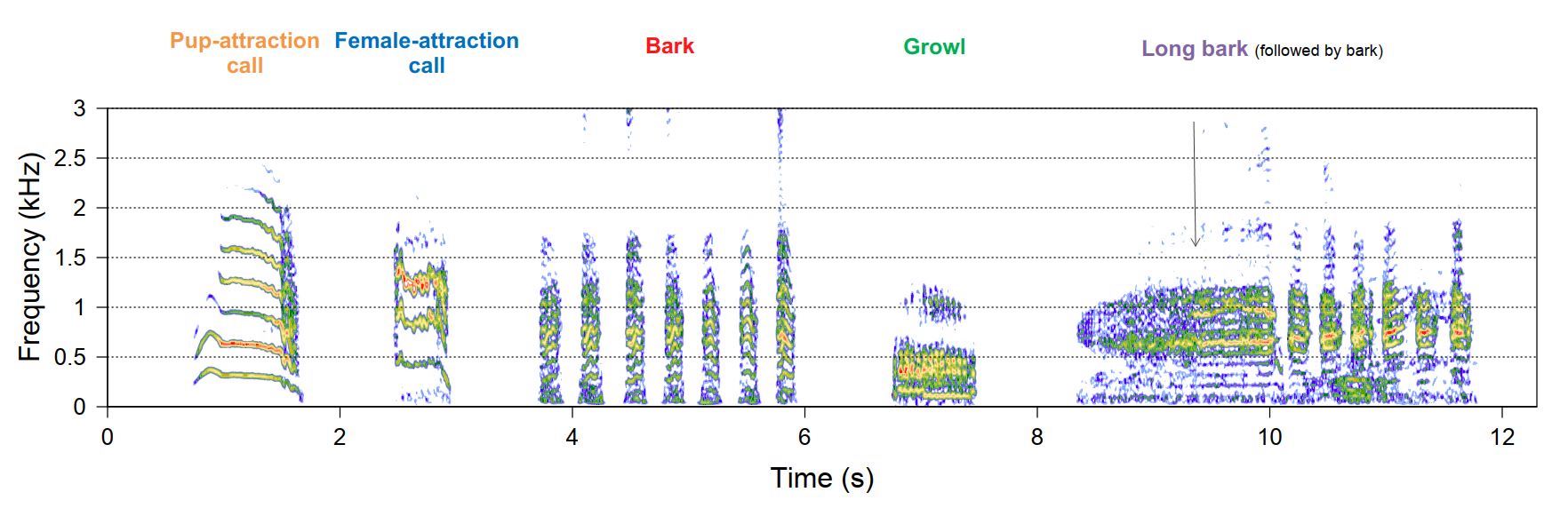

Using microphones, our team recorded 360 seals making over 3800 vocalisations at Pelican Point and Cape Cross during the 2019-20 breeding season. The Pelican Point colony provides a useful contrast with Cape Cross, as the colony is smaller, less dense and occupies a different habitat. Our analysis revealed that Cape fur seals have a relatively small repertoire of five different types of calls. Two of these are attraction calls between females and their pups, while adults communicated with barks, long barks (males only) and growls as part of territorial defence or during close-contact fights. Despite the limited call repertoire, the context in which a call is produced (e.g. mating, fighting) provides enough basic information for other seals to interpret the caller's motivation.

Considering the complex social life of seals, however, we hypothesised that each call would contain more detailed information about the caller – e.g. sex, age, body condition or even individual identity. Our team therefore ran acoustic analyses on seal calls and performed playback experiments to decipher what type of information Cape fur seals can convey in their vocalisations.

We first compared the characteristics of vocalisations (e.g. duration or pitch/timbre) made by seals in different social categories and ages within these categories. We found significant differences between groups and ages. For instance, females produce higher-pitched and shorter barks than adult and subadult males. Similarly, week-old pups produce shorter and more bleating calls than 2-4 months old pups. Finally, we analysed calls made by specific individuals and found that each seal's voice is unique, thus potentially allowing individual recognition within the seal colony.

To test whether or not individual recognition is involved in seal communication, we performed playback experiments by broadcasting vocalisations from particular seals to others that did or did not have a direct relationship with the caller. Initial results from our first experiments showed that both mothers and pups are able to recognize each other from their voice (mothers responded more when we broadcast calls from their pup compared to calls from strange pups, with similar results for pup responses). Moreover, this vocal recognition seems to appear very soon after birth, probably in the early days of the pup's life. Vocal communication thus seems to be the primary way for mother-pup pairs to reunite in the colony after a mother's foraging trip at sea.

Our playback tests on territorial bulls revealed that they react differently to their neighbour's barks than to those from strange males. The bulls appear to be more aggressive with strangers than with their neighbours whom they probably consider to be a lesser threat to their territory. Finally, our investigations showed that territorial males encode their state of arousal in their barks. They bark faster when they are excited or motivated (e.g. during a fight). We found that subadult males – which are too young to hold a harem – responded to our playbacks of adult males with different behaviours based on the level of excitement in the call (e.g. becoming more vigilant when rapid barking is played). Assessing the threat level from barks allows subadult males to reduce the risk of injury posed by aggressive territorial bulls around them.

We compared our results with studies on other pinniped species and found that Cape fur seals had higher levels of individuality in their calls than other pinnipeds. These species live in less challenging circumstances – their colonies are less densely populated, or the males are not territorial, or mothers and pups stay together until the pups are weaned. Cape fur seals have therefore adapted to their noisy, potentially dangerous living conditions by developing unique voices that can be recognised within their crowded colonies.

The Namibian Dolphin Project and the French research team Acoustic Communications are grateful to the Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) for assisting with the research permit application for this project.

The Namibian Dolphin Project is a research and conservation project working in Walvis Bay and Lüderitz, Namibia.

The Acoustic Communications team of the Institute of Neurosciences Paris-Saclay, CNRS & Paris-Saclay University, France, is dedicated to the study of vocal communication processes of animals in their natural environment.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.