Namibia's Updated Nationally Determined Contribution Under the Paris Climate Agreement: Is it Achievable?

9th September 2021

Namibia is particularly vulnerable to climate change, which exacerbates extreme environmental events such as persistent droughts and sporadic flooding. In response to this threat, the Namibian government has a National Climate Change Policy, among others, that addresses related issues. Policies are usually indicative of how governments plan to achieve certain goals. While policies are normally not enforceable, they can at an appropriate stage be developed into binding legislation.

Although Namibia does not have any specific domestic legislation that deals with climate change, it has ratified several international environmental agreements. Under Article 144 of the Namibian Constitution, ratification effectively makes these agreements part of Namibian law. The Paris Climate Agreement that Namibia ratified in 2016 is one such example. Let me provide a quick guide to Namibia's recently updated national commitments that fall in line with this agreement. In particular, I ask whether these commitments are feasible in our current economic context and considering development goals, and what the consequences might be if unrealistic targets are set.

What is the Paris Climate Agreement?

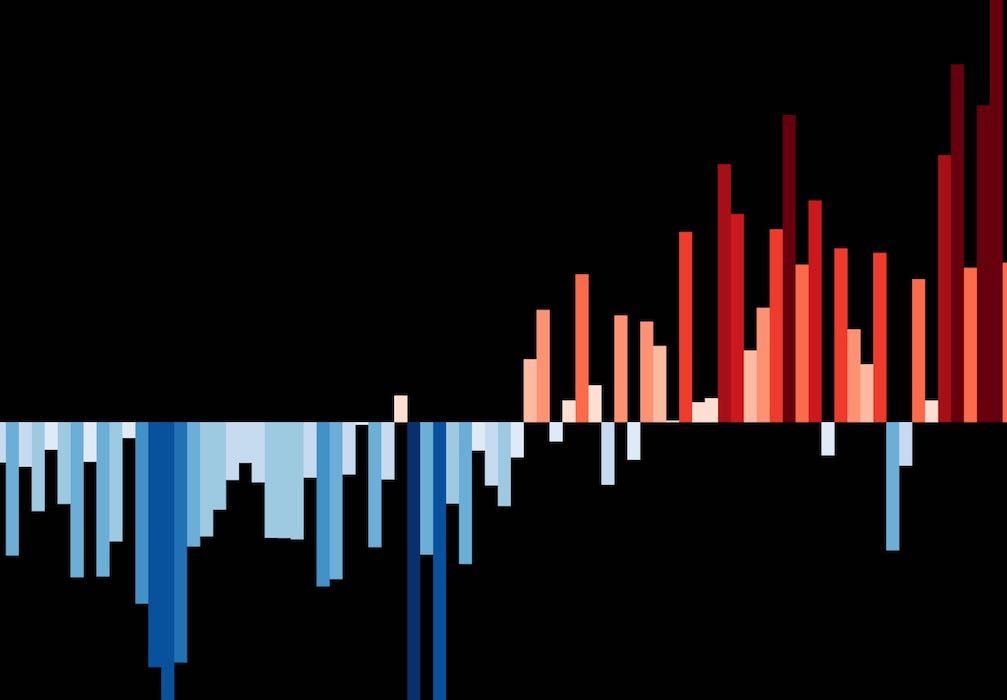

The Paris Climate Agreement was adopted in December 2015 and came into force in November 2016 after a sufficient number of nations had ratified it. With 191 nations on board, this Agreement represents a high level of international commitment to dealing with climate change. The principal aims of the Agreement are to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change, caused by the increase in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty. The signatories seek to achieve these aims by holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C, while pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. One of the ultimate goals for signatories is to reach net zero GHG emissions by 2050 – i.e. that the total emissions produced by human industries are cancelled out by the earth's ability to absorb carbon dioxide.

An important aspect of the Agreement for developing countries like Namibia is the financial support they could receive to lower GHG emissions and encourage climate change-resilient development such as switching to renewable energy. To comply with the Agreement, each country is required to set its own emission-reduction targets, known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), which are reviewed every five years. While the Agreement calls on parties to be ambitious with their NDCs, they must still be achievable within each five-year period.

Namibia's 2021 NDC

Namibia is already a net carbon sink, which means that our natural environment absorbs more carbon (in the form of carbon dioxide) than our industries emit in the form of GHG. Nonetheless, in its 2015 NDC Namibia committed to reducing GHG emissions by 89% by the year 2030 and updated this target to 92% in the 2021 NDC.

Reaching this ambitious goal would include reducing emissions as much as possible and offsetting any remaining emissions through investing in carbon sinks (e.g. restoring natural environments). The NDC focuses on both mitigation and adaptation measures. Mitigation measures mainly deal with reducing climate change, whereas adaptation measures mainly deal with adapting to life in a changing climate. To achieve its 2030 target, the NDC proposes a number of mitigation measures in the energy, transport, forestry, land use, industrial and waste sectors. It also includes significant renewable energy investments, such as switching to hydrogen-fuelled or electric vehicles for the industry and transport sectors.

The estimated costs of these mitigation measures are USD 4.43 billion (or NAD 65.2 billion) by 2030. In addition, the NDC also provides a budget for adaptation costs which amounts to USD 3.22 billion (or NAD 47.1 billion) by 2030. It lists Namibia's agricultural, tourism and fisheries sectors as critical for adaptation. In total, the NDC estimates that Namibia would need USD 7.65 billion (or NAD 112.3 billion) by 2030 to address the impact of climate change on its environment and economic activities. The NDC nonetheless states that only 10% of its commitment will be covered by Namibia's public funds, while the remaining 90% will be conditional on international support.

Is the NDC realistic?

Although Namibia's NDC is ambitious, as encouraged by the Paris Climate Agreement, one has to ask if it is realistic, given our current economic and development contexts. First, it is not clear how the NDC's cost estimates were arrived at, especially those that are to be covered by public funding. Sourcing the necessary public funds would require some major policy reforms and commitments across various sectors of government that are already competing for the ever-shrinking national budget. Given that Namibia's annual budget showed a deficit of 12.5% of its GDP during the 2020/21 financial year and considering the additional financial challenges it will face in recovering from the Covid pandemic, it seems unlikely that sufficient public funding will be available to meet the NDC targets.

Second, the NDC's proposal to drastically cut Namibia's GHG emissions by 2030 might have some adverse effects on the country's existing National Development Plans, Vision2030, and the Harambee Prosperity Plan II. At present, key industries that drive Namibia's economic development remain dependent on GHG emissions-related activities (e.g. transport and electricity). The NDC is silent on how the industrial sector is to rapidly and cost-effectively switch to cleaner forms of energy over the next five years. Given this ambiguity in the NDC, it appears that for Namibia to meet its reduced GHG targets, it would require a continuous, well-coordinated, inter-ministerial and inter-sectoral effort that involves wide-ranging consultation with all of Namibia's stakeholders.

Third, as a net carbon sink, Namibia's emissions are already relatively low, which means that reducing them further is more expensive for our country than it would be for a high-emitting country such as South Africa. For example, the NDC proposes a transition from fuel-driven vehicles to electric vehicles. How this transition will be managed without financially overburdening employers, consumers and aggravating Namibia's already high level of poverty and inequality is unclear. Thus, without a clear transition plan that shows how Namibia is going to convert its fossil fuel-based economy to a renewable energy-driven economy in a cost-effective manner, the reduction of emissions to 92% by 2030 seems impractical.

Finally, one has to consider Namibia's relationship with the international community, from which 90% of the funding for the NDC is expected. The Namibian government's ongoing support of oil exploration activities in the Kavango regions flies in the face of its NDC and poses questions about its seriousness to tackle climate change. Such policy inconsistency sends mixed messages to other governments and private investors who are looking to invest in climate change reduction activities. These institutions will prioritise countries that have a clear, consistent and attractive policy framework. Thus, Namibia's support for continued oil exploration not only undermines its NDC goals but also goes against the Paris Climate Agreement, which explicitly discourages investment in fossil fuels.

The legal implications of not observing the Paris Climate Agreement

There has been much discussion about whether the Paris Climate Agreement is legally binding on parties or not. Several articles in the agreement include the word shall

. For example, article 4.2 reads Each Party shall prepare, communicate and maintain successive nationally determined contributions that it intends to achieve.

Using the word shall

in legal text is generally understood as creating a legal binding obligation on parties.

To use a recent example, the French government was sued by four non-governmental organisations for not implementing sufficient measures to restrict GHG emissions. France has been missing its national targets under the Paris Climate Agreement. The court ruled that a link exists between the ecological damage caused by climate change and the government's underperformance in this regard. The court decided that awarding money was not an appropriate sentence and instead ordered the French government to come up with measures within two months showing how it is going to address the shortcomings in reaching its national targets.

Suing governments so that they comply with their obligations under the Agreement might not always be the most appropriate way to spur them into action. Arguably, the strength of the Agreement lies in the fact that each party has to submit a five-year plan in which they motivate the measures they will put in place to curb the impact of climate change. The threat of losing credibility among peers for not achieving one's goals could also motivate parties to set realistic and reachable targets.

Conclusion

While it is encouraging to see that Namibia is ambitious about setting climate change commitments, there could be severe development trade-offs involved in meeting them. The potential consequences of failing to meet its targets mean that Namibia needs to set realistic goals. Namibia should thus reconsider its NDC target to focus on remaining a net zero emitter by 2030 rather than setting a specific and unrealistic GHG emissions target. It should also ensure policy coherence across all sectors of government, such as not supporting oil exploration. This will send a clear message about Namibia's commitment to tackling climate change, which will be critical in attracting the investment needed to achieve its climate goals.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.