The Future for Conflict African Wild Dogs in Namibia

Is a Metapopulation Approach the Answer?

9th September 2021

The African wild dog is one of the most endangered carnivores in Africa. This species have been eradicated from 80% of their historic home range on the continent. Humans are the main cause of their precarious status, as they are killed as a threat to livestock and farmed game, their wild prey species have been over-harvested in many countries, and their natural habitat has been destroyed.

Additional problems arise from competition with other species, mainly lion and spotted hyaena – these larger carnivores regularly steal their kills, and can be opportunistic wild dog killers. Wild dogs are also highly vulnerable to common diseases found in domestic dogs, like rabies, parvovirus and canine distemper. With huge home ranges of up to 2,000 km2, wild dogs require large areas with sufficient natural prey for resident packs, and safe areas for dispersing groups to move through.

As wild dogs are found in lower densities than most other African carnivores, any uncontrollable events, such as natural disasters or random population fluctuations, together with the ongoing human-wild dog conflict, can compromise the long-term survival of the species. The main driving factor for human-wild dog conflict is the killing of livestock by wild dog packs. Despite an adult wild dog weighing between 25-32 kilograms, they can take down adult cattle by hunting in packs.

With only seven African countries holding viable wild dog populations of 400 individuals or more, it is critical to manage the remaining populations in order to preserve genetic diversity. Besides population management, community education, farmer education and conflict mitigation are the key actions required to reduce human-wildlife conflict. In South Africa, fenced protected areas have become critical for the survival of small populations of wild dogs and cheetahs, which are managed as a larger metapopulation (see below).

In Namibia the main focus is on reducing the level of human-caused wild dog mortalities outside protected areas. Although packs of wild dogs occur in several of Namibia's north-eastern national parks (e.g. Khaudum, Bwabwata, Mudumu and Nkasa Rupara), they range widely beyond park boundaries and are frequently found on farmlands where they come into conflict with farmers.

What is a wild dog metapopulation?

In a natural situation, a group of young wild dogs of the same sex break off from their original pack to form a new pack in a process known as dispersal. Today, many wild dogs are killed during dispersal, as they have to roam widely over farmlands to find members of the opposite sex before starting new packs. Furthermore, if they choose a farm to settle down and make a den for their puppies, they are even more vulnerable to being killed by local farmers.

Human-controlled management of these populations is one way to help dogs move from one safe area to another, whilst maintaining genetic diversity and limiting breeding between related individuals. Managing several populations that are geographically far apart as though they are part of one large population is known as metapopulation management. By mimicking natural dispersal, reserves in South Africa have recorded increases in their wild dog metapopulation since this type of management was implemented.

In Namibia, however, wild dog populations are in trouble in some parts of their range, particularly where they roam through farmlands far from protected areas. Developing a small-scale metapopulation programme for this species therefore seems to be more relevant than ever. With the creation of a working group of different stakeholders, such as non-governmental organisations, private game reserves, researchers, and the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT), it may be possible to establish an African wild dog metapopulation programme here in Namibia.

An experiment on Zannier Reserve

As an experiment to see whether wild dogs could be established on private reserves, which may one day be part of a metapopulation, two wild dog packs were formed between dispersing groups which were rescued on Namibian farmlands and released onto the 8,000-hectare Zannier Reserve by the N⁄a´an ku sê Foundation.

After rescuing two separate groups of siblings (a one-year-old male and female, and three six-month-old brothers) from a conflict situation in north-eastern Namibia, we introduced them to each other to form a pack. The five dogs were released together as Pack 1 on 15 June 2018 and stayed together on the fenced reserve until 12 February 2019 when three of them were shot and killed by trespassers. The two remaining males were returned to captivity, and have since formed a new pack with two adult females that are destined for release in late 2021.

The second attempt involved introducing four adult brothers to an unrelated female, all of which were initially rescued as pups. Pack 2 was released into the reserve on 20 June 2019 and has since produced ten puppies, thus creating a pack of 14 dogs. One of these died from rabies, five others were injured or killed by lions or while hunting (gemsbok defend themselves using their sharp horns), and the alpha female was removed for bonding designed to further pack formation for future releases. As of April 2021, there are seven wild dogs remaining on the reserve and six others in captivity awaiting release.

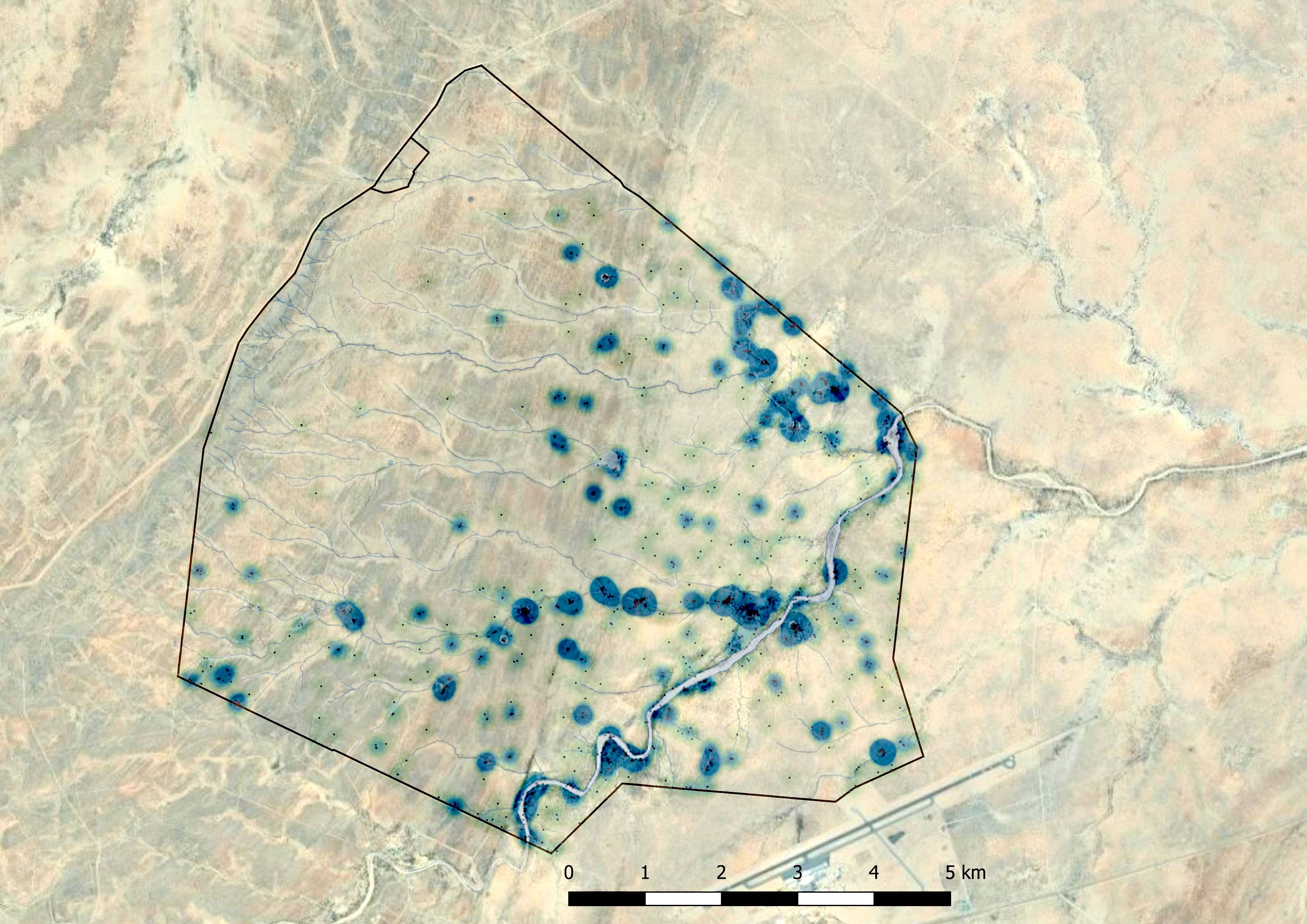

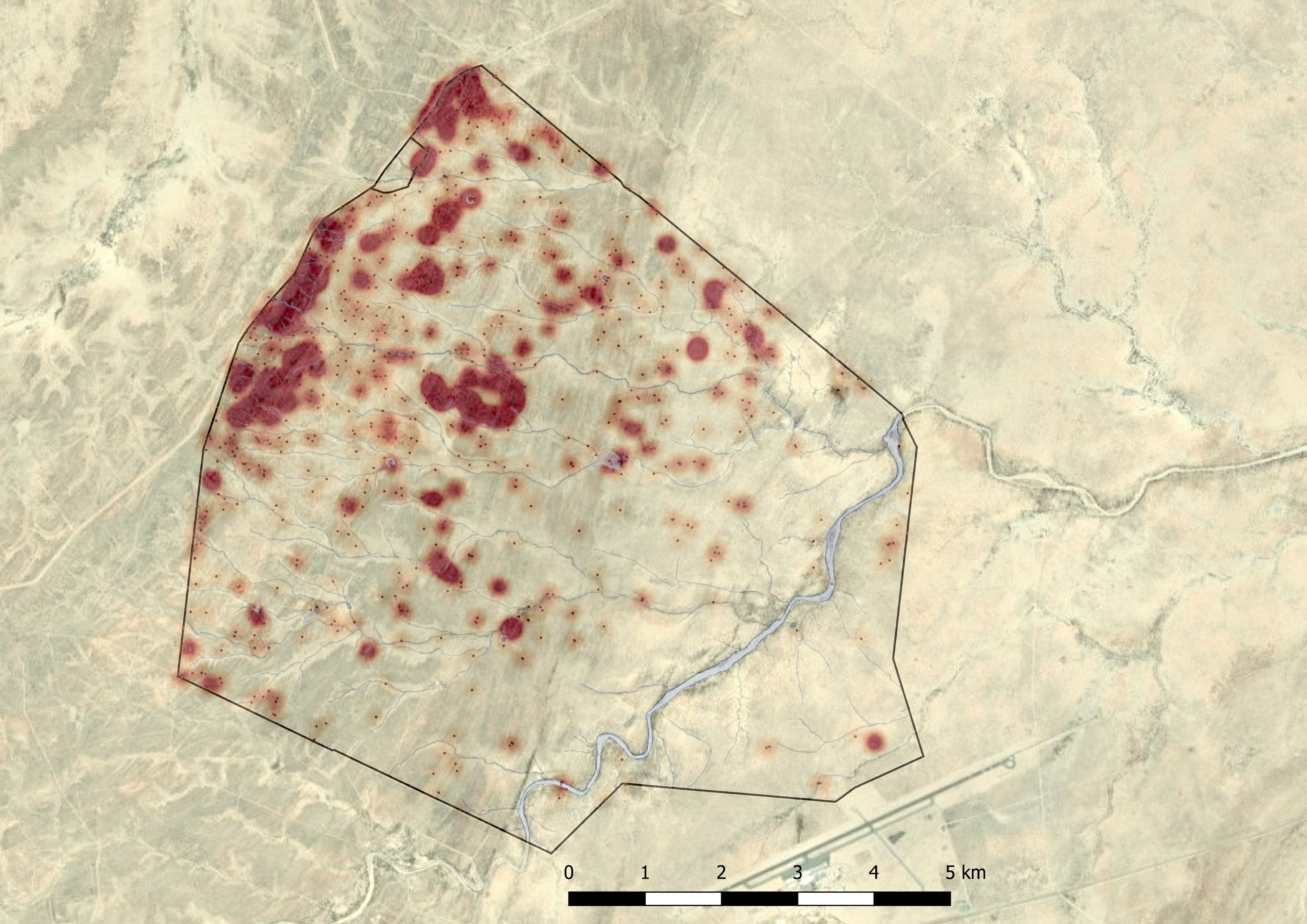

The dominant females in both packs were collared using a global positioning system (GPS) and radio tracking collars. The resulting GPS data were analysed to identify cluster points that indicate where the dogs spent more time than usual. The research team investigated each site to determine if the dogs were just resting, creating den sites, or feeding on a kill. This information creates a detailed picture of how the released packs are faring on the reserve, which is important to explain the success or failure of this experiment and inform future attempts to release packs.

The dogs' movements were compared with movements of the lionesses that were released in October 2018 to determine if the wild dogs and lions used different areas of the reserve. We found that the different species used hunting areas and water sources on opposite sides of the reserve during a one-year period. Of the three pup mortalities in Pack 2, only one was due to lions – this occurred during a hunt when the pack came upon the pride of lions, which then caught and killed one pup.

Of the three adult mortalities in Pack 2, two were attributed to injuries caused by hunting, while the other was a rabies infection. All adults from both reintroduced packs received a minimum of three rabies vaccinations, administered on an annual basis, prior to their release. Designed for use in domestic dogs with an extremely high success rate, its efficacy and duration of immunity in wild dogs is unknown. After the confirmed case, all the pups on the reserve were remotely vaccinated with a rabies vaccination. No additional cases of rabies in the pack have been observed.

Neither of the two packs reintroduced on the reserve have breached or attempted to breach the boundary fence. Pre-release, the adults of both packs were kept in enclosures surrounded by fences with electrified wires on the inside and outside of the fence. During this time they learnt from accidental exposure that touching the fence produces a shock. As a result, the adults avoid the main reserve's fence and appear to have taught the pups to do the same.

Important lessons learnt

At this stage, we consider the release of wild dogs onto Zannier Reserve to be relatively successful, when compared with other attempted releases in southern Africa. The data collected from the Zannier Reserve shows that the packs can hunt and fend for themselves, despite being brought into captivity at a young age. This is a promising sign for future releases of dogs that are rescued from conflict situations when they are still young. Further, the birth of ten puppies from dogs that would have been killed on farmlands shows the potential for fenced private reserves to provide a safe haven for this endangered species.

If packs that otherwise would be destroyed were to be relocated to private game reserves or national parks instead, a metapopulation programme similar to South Africa's could be initiated. The metapopulation could serve as a reservoir for larger reintroductions into national parks such as Etosha or Mangetti in the future. Such a programme could provide parks with wild dogs which are vaccinated against diseases, used to electric fences, and able to avoid larger carnivores like lions. However, working together with farmers and local communities is something that cannot be forgotten. A metapopulation programme will not succeed if the nation does not see the value of this species, or if the human-wildlife conflict issues are not addressed.

Wild dogs are especially valuable for tourism, as they are on the must-see list of many reserve and park visitors. A metapopulation strategy that includes private reserves therefore has the added benefit of generating value from this species through tourism. On farmlands where little or no tourism has been developed, they are perceived only as a nuisance and an unwanted cost. The metapopulation strategy therefore has many possible benefits, and we would like to see other stakeholders join us to make a Namibian wild dog metapopulation programme a reality.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.