Towards healthy environments and decent livelihoods

10th November 2023

10th November 2023

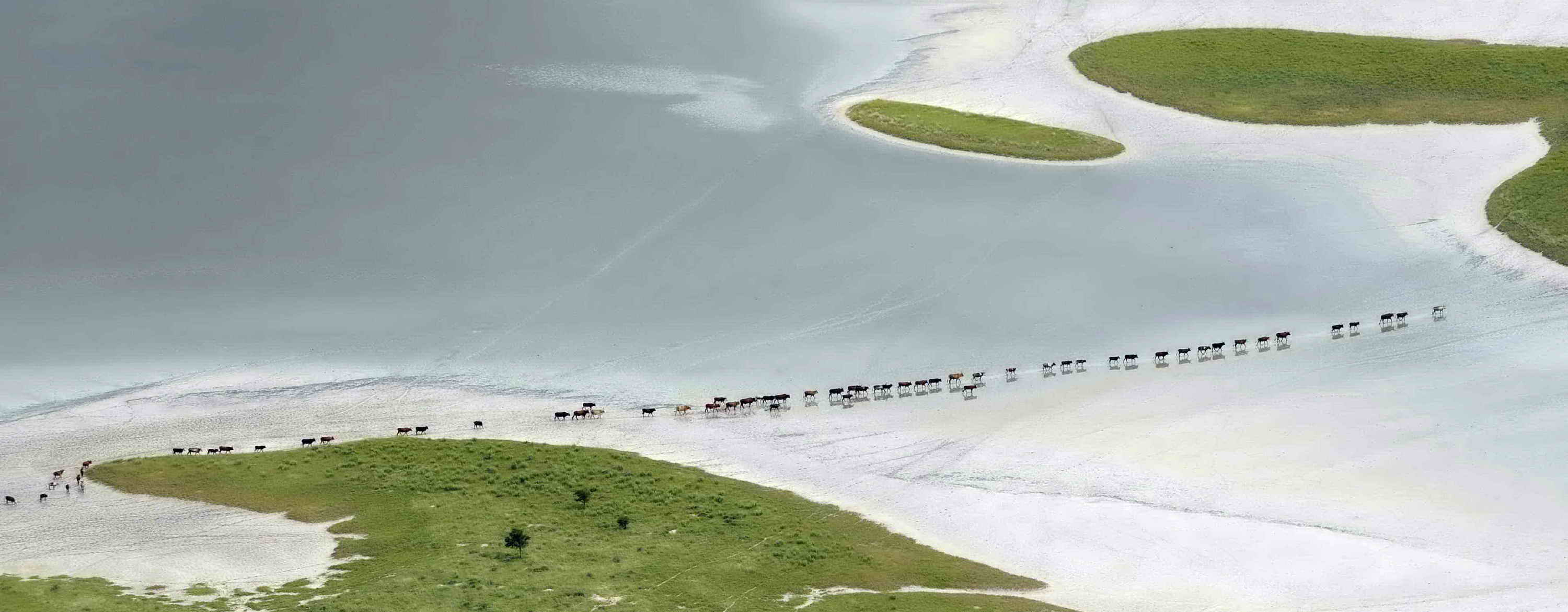

Two big challenges afflict Namibia: poverty and environmental degradation. Both problems are largely concentrated in rural areas where most people are poor, and where considerable areas have been stripped of woodland and forest and of pastures by shifting agriculture and overgrazing. In Namibia the problems are interlinked in many areas, and across the world these challenges receive much attention, for example to end poverty via the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and commitments to counter the effects of climate change. At COP26 held in Glasgow in 2021, world leaders agreed thus: We commit to working collectively to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030 while delivering sustainable development and promoting an inclusive rural transformation.

Two questions about these problems: what are their causes, and how can they be addressed?

Answers are offered by a few fundamental features that make Namibia what it is. Most telling is the poor quality of soil, which limits yields of our main cereals – millet (mahangu), sorghum and maize. Together with Botswana, Namibia has the lowest yields in Africa, and this is the main reason why both countries have small populations, as does much of the continent. Soil quality is the major determinant of rural wellbeing simply because food production and nutrition have such strong effects on the health, wealth and survival of people. In Namibia most soils are variously hampered by their shallowness, limited water-holding capacity, low organic content, poor structure, or low content of different nutrients. Rectifying these deficiencies is very expensive, and only possible if farmers reap high returns from harvests to make their costly investments worthwhile. Similar circumstances prevail in large areas of Africa where soils are poor, crop yields low, malnutrition and poverty rife and populations are small.

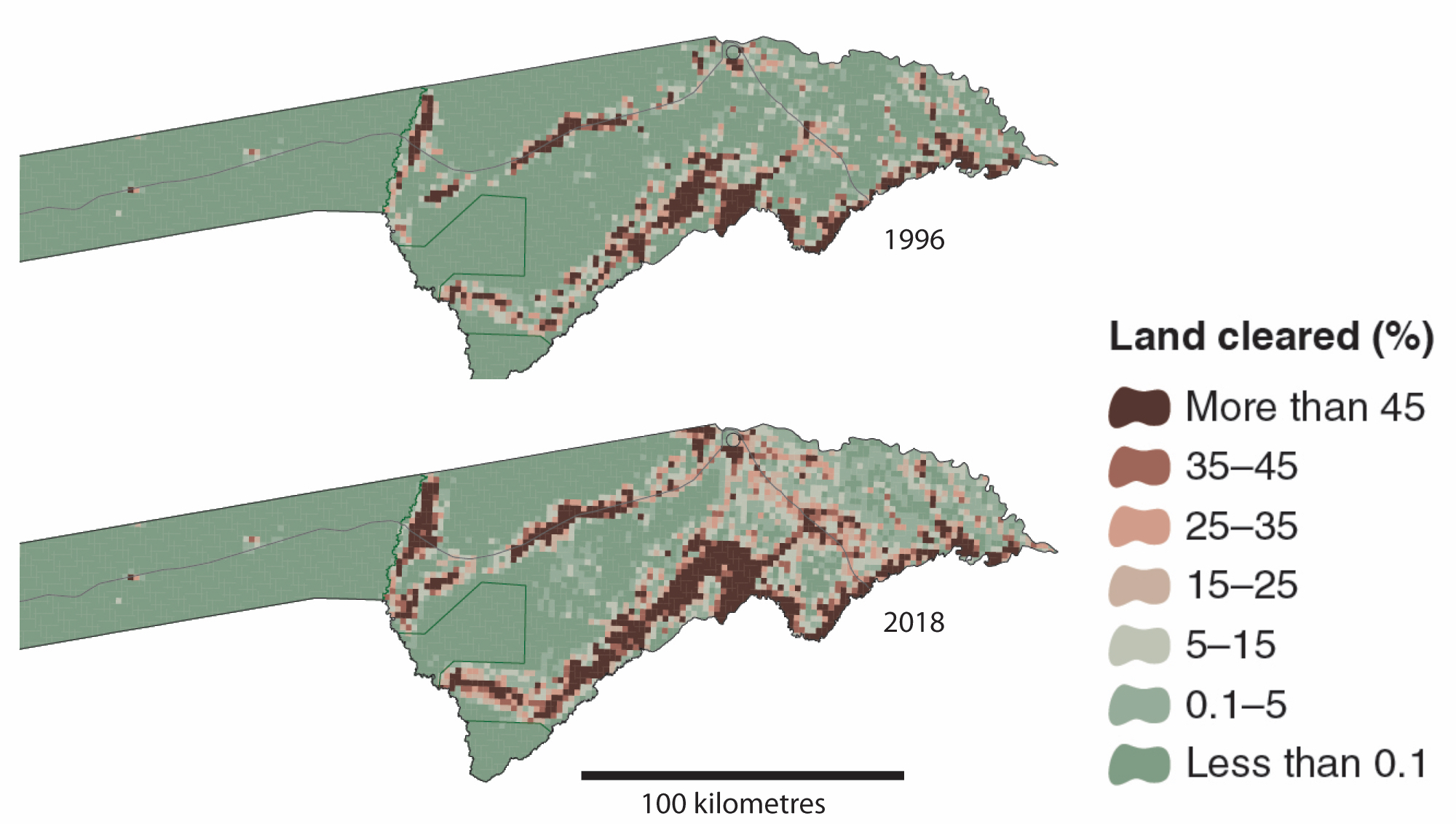

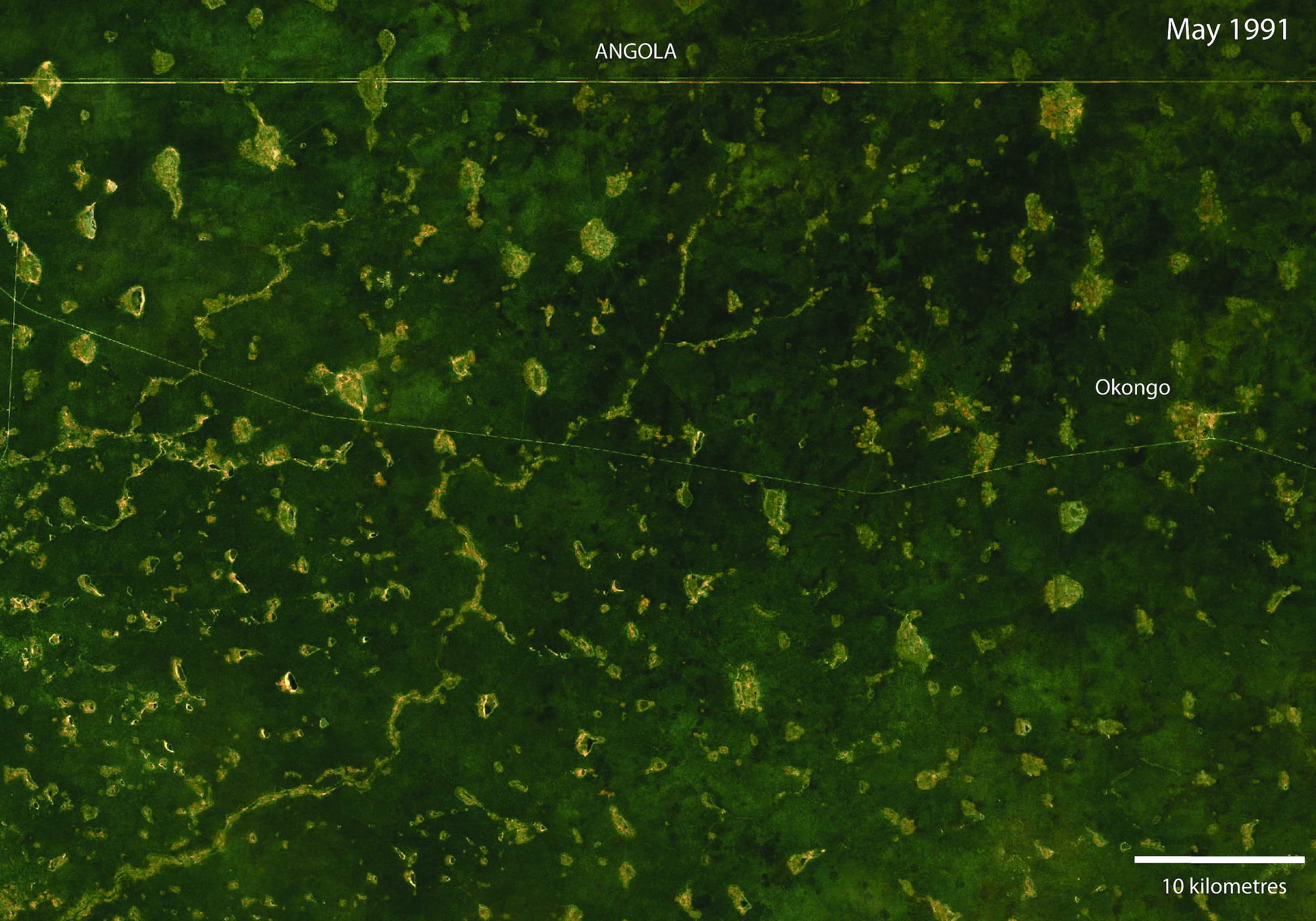

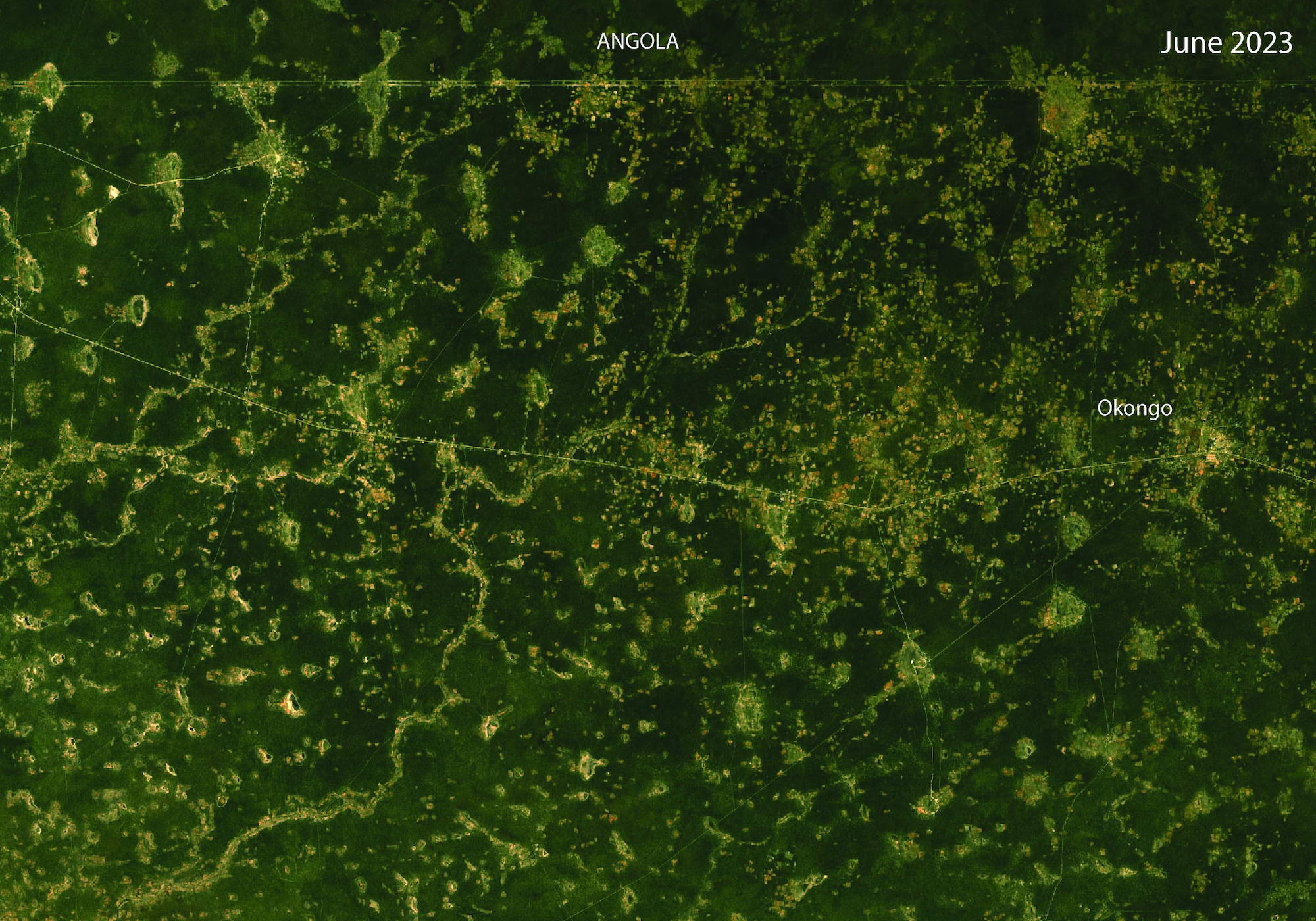

Poor soil fertility is also the primary cause of shifting agriculture and therefore land degradation. Crops soon deplete the limited supplies of soil nutrients, compelling farmers to clear new fields every few years. Great swathes of wooded and forested land on poor soils have been decimated for these reasons across Africa. For example, in the 15 years before 2015, shifting agriculture led to the loss of 363,000 square kilometres of woodland and forest in sub-Saharan Africa. That is close to half the size of Namibia. In this country, about 100 million trees had been killed by shifting agriculture by the year 2000, and some three million more trees are lost in the same way each year. Cleared land takes decades to recover, again because of the poor quality of its soil.

Three other factors often jeopardise yields in Namibia: high rates of water loss due to evaporation and transpiration, inadequate or irregular rainfall, and diseases and pests. Even with good yields, options for earning income are often limited because markets where surpluses can be sold are unreliable, offer low prices or are hard to reach, and because long histories of failed harvests and famine mean that prudent families are reluctant to sell surpluses. Productive – let alone profitable – farming is not easy where environmental conditions are so tough. Farming also requires hard work. That and other investments are only worth making if the returns and incentives are attractive.

While food insecurity and malnutrition have been constraints for centuries, most Namibians are now also tormented by another limitation: income insecurity. This is a severe impediment of the 20th and 21st century. If you think otherwise, run this experiment: leave all your money and debit cards at home for a week. Without income, people don't have clothes, transport, or the means to communicate over distances, or to buy soap, candles, salt, supplementary food, or medicines. Income deficiencies retard access to education, job opportunities, housing, energy, sanitation, information, contacts, ideas and social status. These are essentials, not luxuries. For many Namibians being without money is a long-term endurance, not a brief experiment.

Few of us will grasp how living in a shack in town is preferable to life in the village, especially when we haven't spent time in rural homes where access to money is usually very, very limited. True, some rural households have incomes from remittances, pensions or jobs in schools, farms, lodges and shops. These incomes free them from dependence on local soils and other resources. However, the only option for most people – and all young people wishing to get ahead – is to leave for a town or city where a decent future is possible. As the saying goes 'money makes the world go round'. In Namibia, too.

How can these challenges be addressed?

Many people living in the communal areas of Namibia could – and should – be better off, and the same should be true for many woodlands and forests. While different forms of land degradation are also a challenge on freehold land and resettlement farms, this article focuses on communal lands because of the high number of people affected.

As obvious as it may be, a first step is to achieve political agreement on the need to foster the development of decent livelihoods. Patronising assumptions that rural Africans prefer to live in the bush, that food security is their main need, that they are ignorant and don't need capital, that livestock are simple commodities for sale and that Africans are farmers by nature, must be abandoned.

Firm distinctions are needed between programmes that aim to develop Namibia and those that seek to alleviate poverty. Do government and donor programmes place emphasis on the promotion of food or financial security, the reduction of poverty or creation of wealth, the development of the formal or the informal economy, the stimulation of rural or urban development, or on the development of resilience or dependence, for example?

Truthfulness is vital. It is misleading to suggest to people living in remote areas on poor soil that they will have decent livelihoods once we upgrade their water and sanitation systems, build them a school or clinic, or teach them better ways of farming! At best, poverty will be perpetuated, perhaps with slightly less discomfort. Worse is the possibility that poverty will grow if promises of improved livelihoods in depauperate areas are believed. Of course such people need all the help they can get. But the help should then be charitable, preferably through social grants that provide essential income, and it should be progressive in offering people and their children viable opportunities to fully escape poverty. The goals of development assistance must be clear and realistic, not vague or founded on false hopes.

Government and donor programmes that seek to deliver development need to be directed to fertile ground where food and financial security go hand in hand. It serves little purpose to invest in areas where incremental increases in crop yields just might provide farmers with a 10% gain over their current income, when what they currently receive is so meagre. A boost from N$2,000 to N$2,200 per year will have very little impact on the living conditions of a farmer and her or his family. Support for subsistence farming often only helps to keep Africa and Africans poor.

The most obvious need is to focus crop production in places where people can farm and trade profitably, earning incomes from their produce while enjoying access to the necessities of modern life. Most such places are close to towns where peri-urban farmers can sell their produce in nearby markets, and close to shops and good education, health and other services that are often only available in urban centres. These are also areas where most young Namibians want to be because they offer the best chances of having decent livelihoods. Why should people live in food-based subsistence economies in depauperate areas if cash-based livelihoods are available in urban and peri-urban areas?

Urban centres are growing rapidly, which is even more reason to support their orderly development. These are the places where Namibia can reduce poverty most effectively and significantly. Many more resources should be invested in urban areas, surrounding peri-urban farming zones and services that supply water, sewerage systems, transport, education and health, as well as proper land tenure for residents. Urban development in Namibia has largely been informal in recent years – now is the time for the ordered development of towns and cities to attract people to benefit from greater food and income security.

As tough as this sounds, along with developing commercial agriculture close to urban markets and services is the humane need to discourage people from living where poverty and malnutrition is rife, yields are low, surpluses are rare and/or hard to sell, services are distant, and where new fields must be cleared continually.

Apart from raising the living standards of a high proportion of Namibians, these changes could yield benefits for Namibia's natural environment. For example, with better income security, poaching and exploitative trade in freshwater fish should decrease, and vegetation that recovers will store more carbon dioxide to ease global warming. Virgin land unsuited to crops will continue to provide these and other ecosystem services to Namibia and planet Earth for present and future generations. Namibia will also gain more distinction for its preservation of natural habitats and wildlife, and the economic values and comparative advantages of our natural environments will grow as other wildernesses elsewhere in the world shrink. Ideally, this land should be open and undivided to allow free animal movement, rather like the commonages and other unfenced land should be in communal areas. How could it be managed?

Like communal land? Hopefully not, if its management over the last 33 years is anything to go by. Rather than being maintained as open, common property providing resources to benefit the poor as per the Communal Land Reform Act, much communal land is progressively being taken by affluent Namibians. As a result, the small numbers of animals kept by local, poorer residents can't compete for forage and water with the substantial numbers of cattle, sheep and goats belonging to people who make a good living from businesses or lucrative jobs in towns far away. In addition to these extensive areas of appropriated grazing are the large areas of commonage fenced and expropriated by the affluent with the collusion of traditional authorities, especially in Kavango East and West, Oshikoto, Ohangwena, Otjozondjupa and Omaheke.

Namibia seems to have abandoned its stated intention for communal land to be a safety net, and so the poorest of its citizens suffer the most. Among them are !Xun and Ju/'hoan people, who continue to be dispossessed of their land and its resources decades after independence. Commonage or common property resources which give value to conservancies and community forests have also dwindled as more and more of their gazetted land has been appropriated or expropriated. Large areas of communal land are now severely overgrazed – another environmental calamity.

Promoting appropriate land uses and the orderly use of common-property natural resources requires firm controls. Seretse Khama, the first president of Botswana, made this clear in a speech that applies as much to Namibian communal areas as to his own country: Under our communal grazing system it is in no one individual's interest to limit the number of his animals. If one man takes his cattle off, someone else moves in. Unless livestock numbers are tied to specific grazing areas, no one has an incentive to control grazing.

He made this logical point 48 years ago!

Secure tenure over land is a necessity if its resources are to be managed for sustainable use and value for their intended beneficiaries. The idea that anyone can move in and around communal land to graze hundreds of livestock is not tenable. Communal land can no longer be 'a free for all'.

FOR THE FUTURE

Adoption of five key strategies would advance the development of wealth for people and healthy environments. First: Namibia should promote urban development, especially in lower income, informal areas. Second: crop farming should be supported where it can be profitable, so that people can have decent livelihoods. Third: people should be discouraged from living in places mired in poverty which require shifting agriculture. Fourth: land uses must be truly suited to their target lands, which means that areas not suited to human occupation should be preserved for their ecological values and the services they provide. Finally: land tenure systems should be tailored to the best uses of land and needs of Namibians.

The ideas expressed here have been incubated over 25 years of trying to measure and understand how poor people make a living in both rural and urban areas of Namibia, and in Angola and other parts of Africa, and how land is managed and mismanaged by governments, traditional authorities and local authorities. This article benefited from comments on earlier drafts provided by Chris Brown, Helge Denker, Bennett Kahuure, Stephie Mendelsohn, Ara Monadjem, Ndapewa Nakanyete, Nyambe Nyambe, John Pallett, Chris Shatona, Hannu Shipena and Gail Thomson. I hope the article stimulates more critical thinking about development, poverty, the management of resources and land, and the natural environment. Namibia has much to gain.

Readers who want to know more about the challenges and opportunities in Namibia, including the topics covered in this article, are encouraged to read the Atlas of Namibia (2022) available in hardcopy or at https://atlasofnamibia.online.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.