Endemic plants and animals on the highlands of Namibia and Angola

20th November 2024

20th November 2024

Africa has many special features. Among them is the exceptionally high plateau stretching across the southern half of the continent and rising 1,000 metres and more above the surrounding Atlantic and Indian Oceans. A large part of this plateau forms the great Kalahari Basin, renowned for being the biggest continuous area of sand on planet Earth.

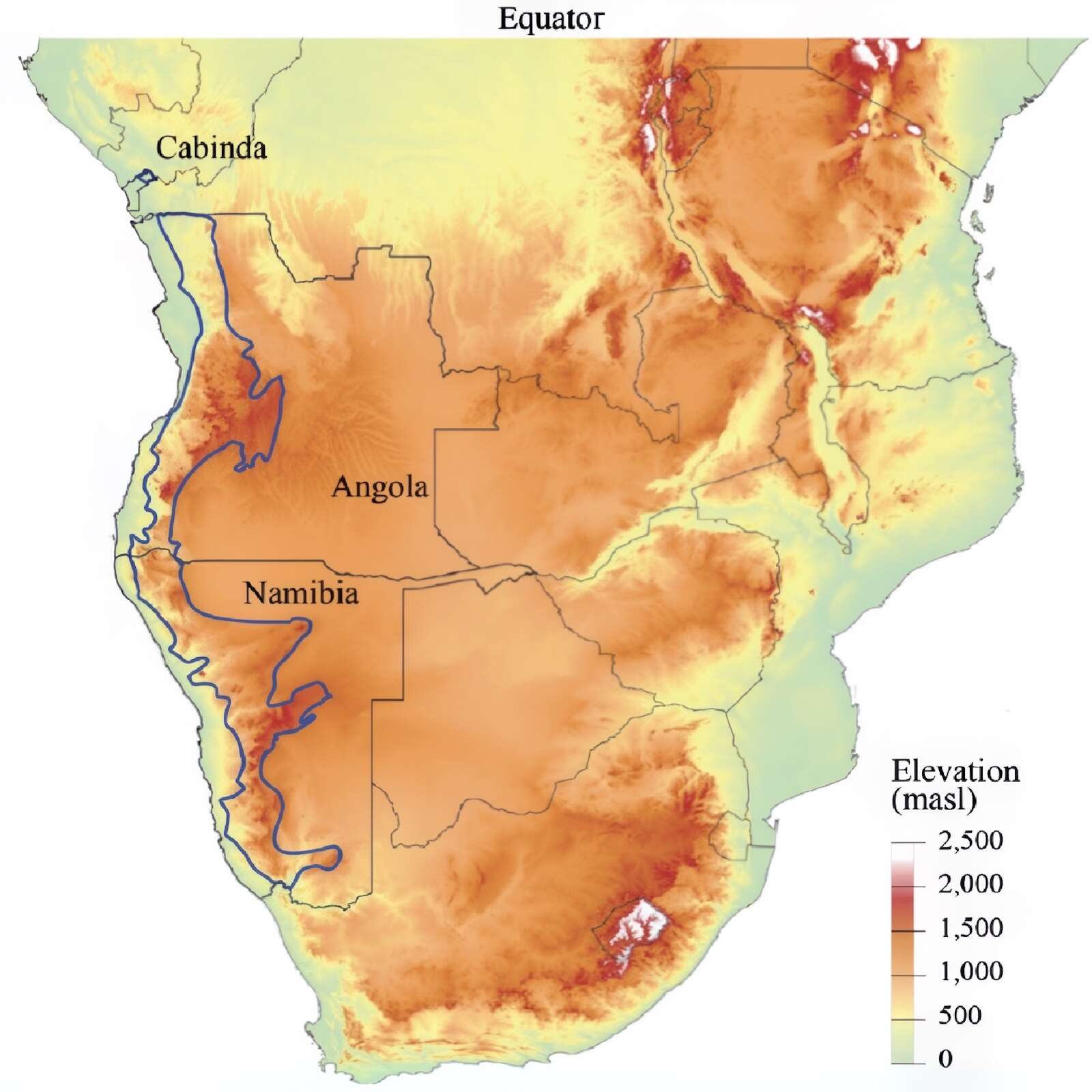

Another special feature is the Great Escarpment, which encircles this plateau. In the west the Great Escarpment stretches south from Gabon through Angola, Namibia, into South Africa and then east and north all the way to Ethiopia. In many areas the Great Escarpment and its peaks rise to 2,000 metres or more. Most rivers either flow rapidly down to the surrounding coast or lazily into the broad plain encompassed by the Great Escarpment.

Biologists have long focussed their attention on species found only on these highlands. Studies in the Ethiopian highlands, Tanzanian Eastern Arc Mountains, Zimbabwe Eastern Highlands, South African Drakensberg and Cape Fold Mountains have made these areas famous for their endemics, the term for organisms found only in certain restricted areas. However, relatively little information was available about endemism on the highlands of Angola and Namibia.

The Namibian Journal of Environment recently published a review written by 64 people from around the world, most of them specialists in their fields of study on particular groups, for example euphorbias, petalidiums (petal-bushes), reptiles and butterflies. The review consists of 26 articles and runs to 338 pages. Individual articles or the whole book can be downloaded for free.

Broadly, the review seeks to answer five key questions:

- What characterises the highlands’ structure, climate, biota and land uses?

- How diverse are the taxonomic groups represented in the highlands?

- How many endemics have been catalogued there?

- Where are centres of diversity and endemism located within the highlands?

- How are highland species and subspecies related to similar plants and animals found elsewhere in Africa?

The monograph focuses on the highlands and escarpments that stretch some 2,700 km from Cabinda and the Congo River southwards to the Orange River on Namibia’s border with South Africa. Two plateaus 1,700 metres and more above sea level (masl) cover large areas: the Angolan Planalto and Namibia’s Khomas Hochland. Both occupy central areas in their respective countries. Numerous inselbergs (isolated mountains) rise above the landscape, and many scarps form sharp margins between lower, western and higher, eastern areas. The highest peaks rise to about 2.5 kilometres above the sea, the best known in Namibia being the Brandberg (2,573 masl) and Moltkeblick (2,489 masl) on the Auas mountains.

Average annual rainfall ranges from about 1,200 mm in the north of Angola and on the Angolan Planalto to less than 100 mm in the far south of Namibia. To the south, declining rainfall as well as increasing evapotranspiration make the southern areas much more arid than those to the north. As a result, verdant tropical forests characterise the northern parts of this western section of the Great Escarpment while its southern areas support sparse covers of small grasses, shrubs and succulents.

The monograph begins with chapters summarising its main findings (to which I will return), and the ecoregions, and physical and human geography of HEAN – our acronym for the Highlands and Escarpments of Angola and Namibia. Other early chapters present detailed maps of the HEAN, the geology and landscape evolution of these highlands, and the challenges facing the conservation of Angolan highlands.

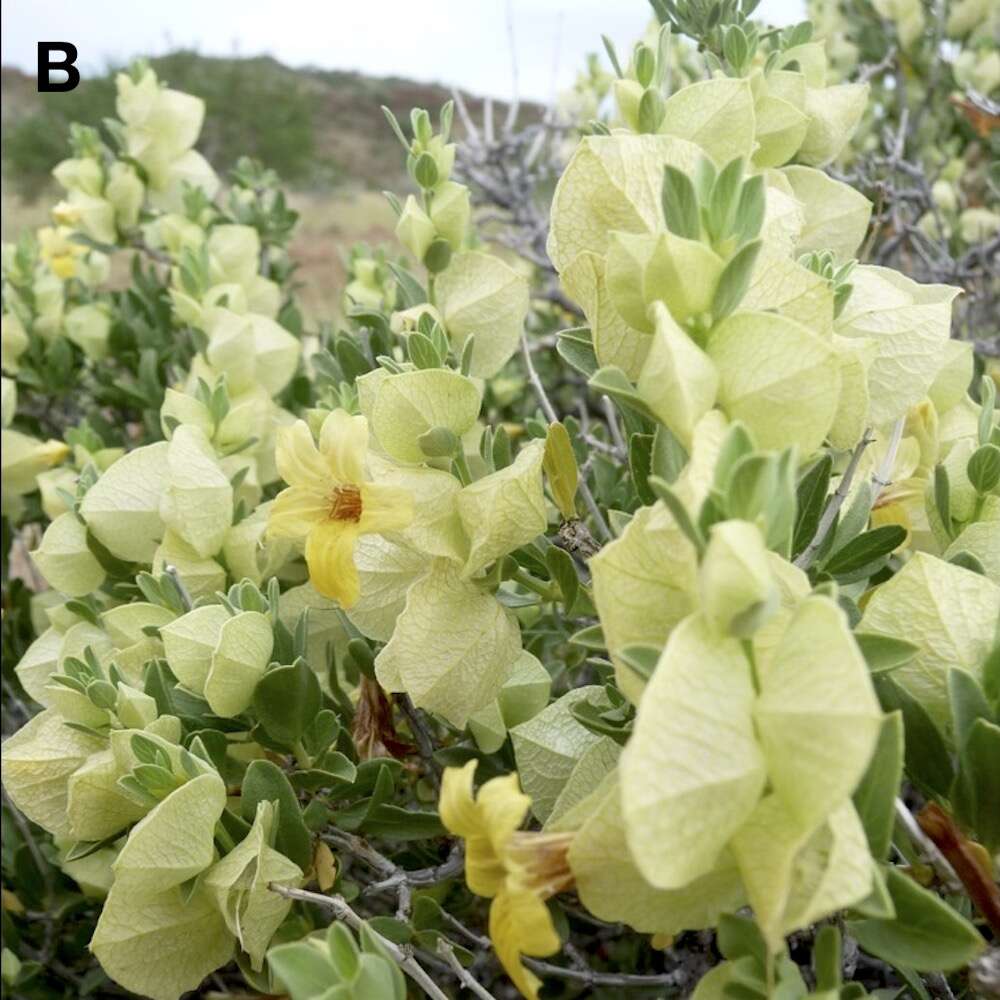

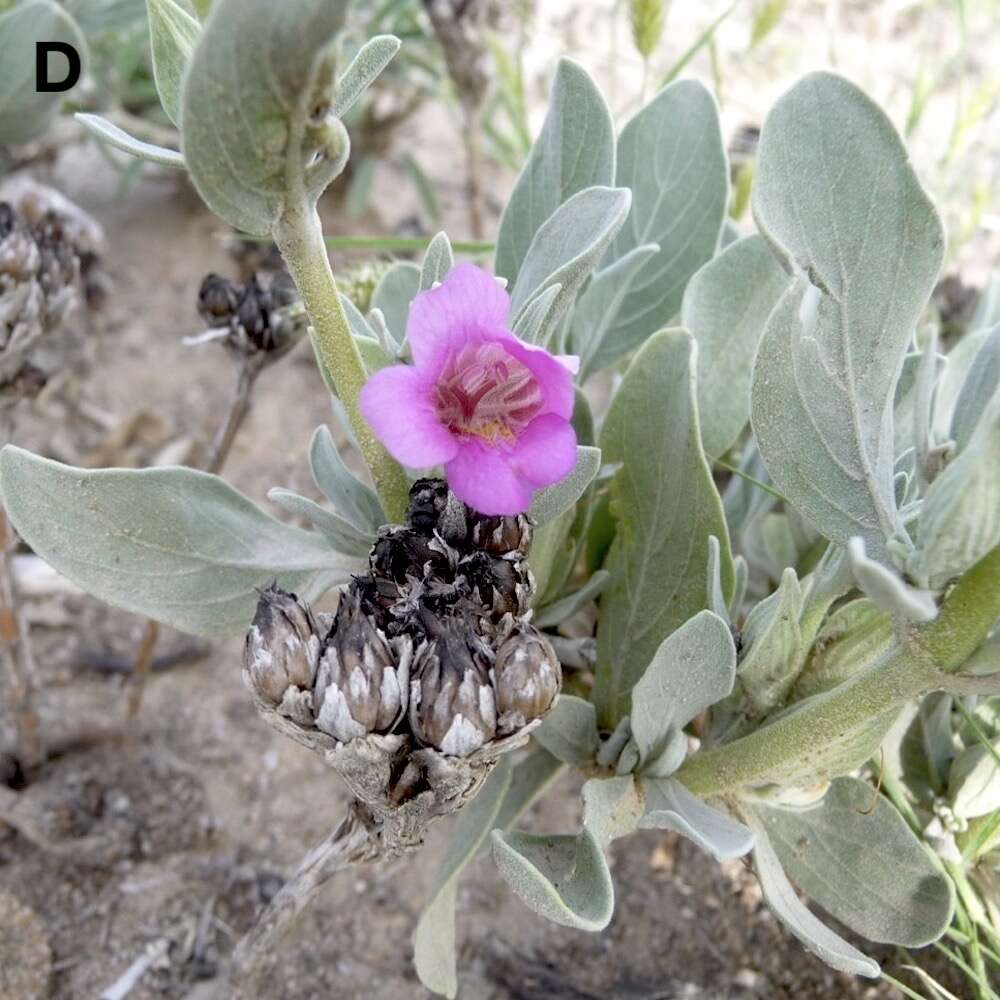

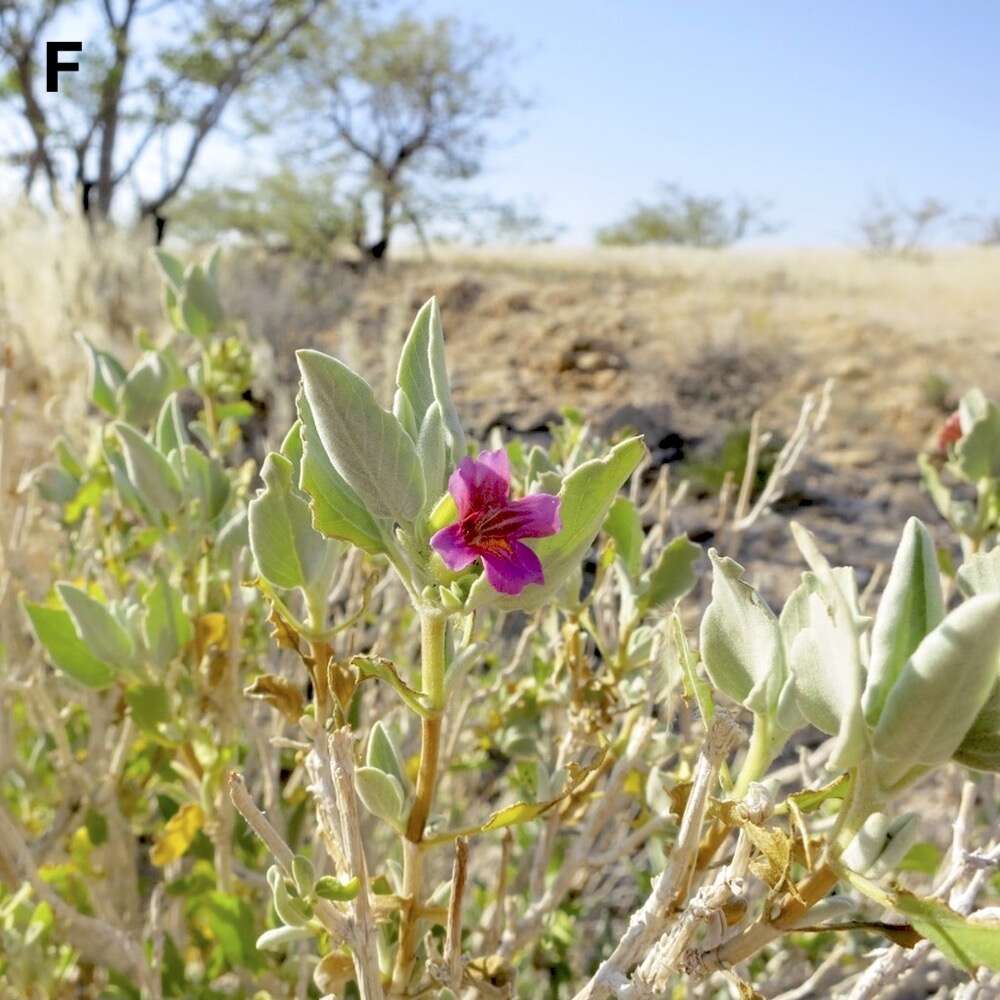

Then follow chapters on the HEAN’s endemic arachnids (spiders, scorpions and allies), birds, reptiles, flat geckos, ants, lacewings and antlions, termites, mammals, frogs, reptiles, fishes, Petalidium plants, Ceropegieae and euphorbia plants, and commiphoras.

Other chapters focus on endemism in certain areas: plants on and around Angola’s Mount Namba, plants and animals in northern Angola’s Serra do Pingano mountains, plants in Namibia, underground geoxyle plants on Angola’s central Planalto, and dragonflies and damselflies in Angola, and animals occurring mainly in caves.

Namibian authors who contributed include Roy Miller, Wessel Swanepoel, Leevi Nanyeni, Frances Chase, Alice Jarvis, Pat Craven, Francois Becker and Herta Kolberg.

What was found?

Lots of endemics! Among the taxa reviewed at least 570 known animals and plants are now known to be endemic to the HEAN. But the number would be quite different if other groups could have been added to the review. These include groups that have many species, such as beetles, flies, bugs, crustaceans, round (nematode) and segmented (annelid) worms, snails and allies, mosses and allies (bryophytes), algae and others.

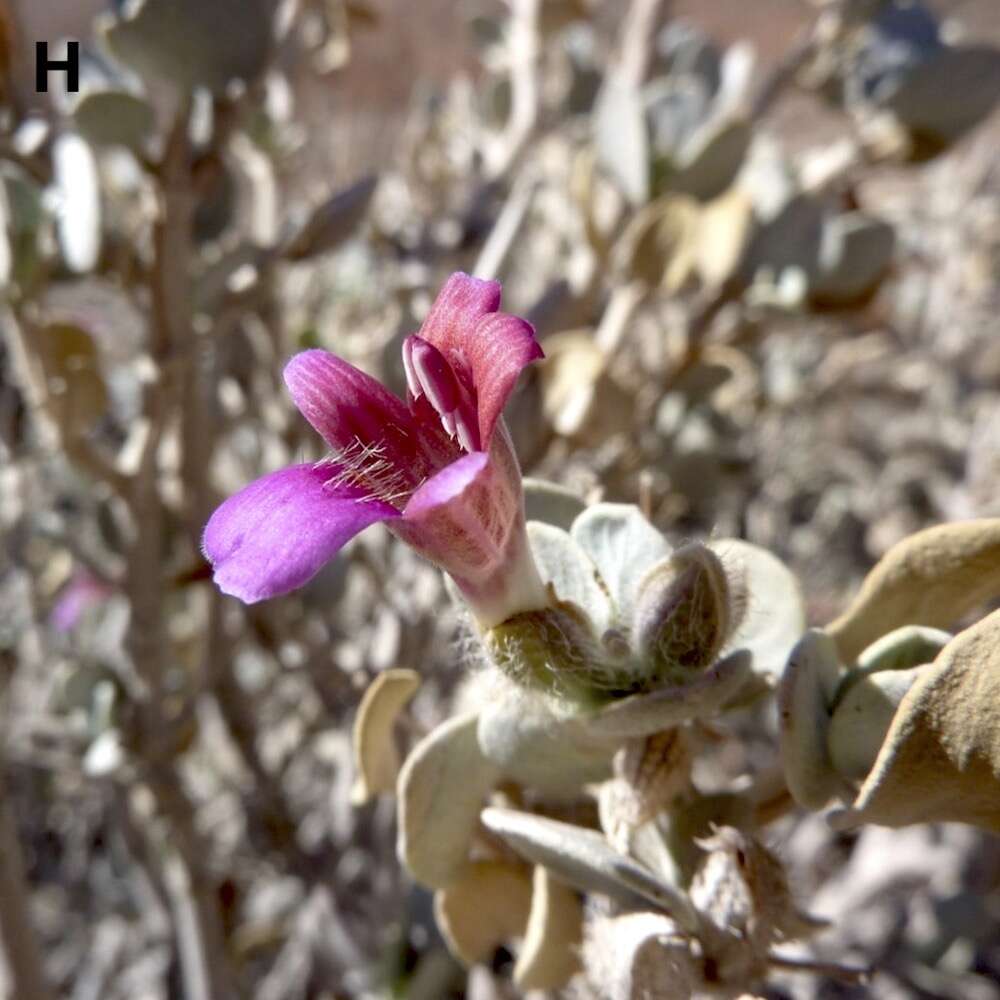

In Namibia, of some 4,000 species of indigenous seed plants, over 100 are known only from the highlands. In their chapter, Pat Craven and Herta Kolberg found that Brandberg is home to over 480 indigenous seed plants, of which about 90 are Namibian endemics and nine are limited to the mountain itself. Kyle Dexter and his coauthors found that 22 of the 36 African species of Petalidium are endemics or near-endemics to the HEAN. Among the 570 endemics found in this area, some are particularly charismatic and well-known among naturalists, such as Angola Dwarf Galagos, Angola Cave Chats, and Swierstra’s Francolins.

The authors of the articles in the review would agree on several priorities. Special emphasis should be placed on exploring neglected regions and habitats within the HEAN. We also need to take stock of endemism among other taxonomic groups not covered in this publication. Effective conservation measures are urgently required to protect the fragments of relict forests, grasslands and savannas that carry the products and evidence of many millions of years of evolution. These habitats are progressively decimated by frequent hot fires, charcoal production and the clearing of woodlands and forests for shifting agriculture. Pedro Vaz Pinto and his coauthors working in Angola stressed the urgency of conservation interventions in the country.

Perhaps the most striking conclusion is how little is known about most plants and animals that live only on our highlands, and for which Namibia and Angola are fully responsible. Much of this ignorance is due to a scarcity of records in museums, herbaria and digital databases, such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). But there is also a great shortage of students and scientists who study different groups of organisms.

The collection of specimens, fieldwork, and studies of biogeography, taxonomy and systematics are no longer fashionable. Indeed, much of the information on which humanity now relies was collected by hardy, brave explorers, missionaries and naturalists who trudged their way across Namibia, Angola and beyond 50, 100 and 150 years ago. Where is the new generation of naturalists to fill the gaps and document recent changes? How many species known to scientists in Angola and Namibia a century ago no longer exist? We can only dream about those we don’t know, and never will!

Acknowledgements

Great credit goes to the Ongava Research Centre and Namibian Chamber of Environment for material and financial support. Similar support from the institutional homes of the many authors is likewise acknowledged. More personally, I am indebted to Brian Huntley and Pedro Vaz Pinto for their help in editing the volume and to Alice Jarvis and Carole Roberts for their dogged determination to get the language, style, and layout done correctly!

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.