NCE Supports: Assessing Namibia's Energy Options

15th November 2025

15th November 2025

Namibia stands on the cusp of change in its energy sector. Oil, bush biomass, and green hydrogen are appearing on the horizon, making coal, hydropower, solar panels, and wind turbines seem like yesterday's news. Promises of jobs and economic growth come thick and fast from some of the new sectors, leaving the average member of the public reeling and uncertain about which option (or options) to support.

As we stand at the crossroads, Namibia must decide which energy future will best serve its people. To do that, we need to look beyond the press releases, the hype, and the exaggerated promises, and base our assessment on reality and evidence in an even-handed manner. This guide to various energy options aims to inform Namibian citizens and policy-makers about the potential benefits and pitfalls associated with each form of energy. We also consider an option that has been generally overlooked in the past: nuclear power.

As we assess each source of energy, we keep in mind Namibia's unique context that tips the balance one way or the other for each industry. Namibia is in desperate need of jobs, and its economy is faltering. High economic inequality and a critical housing shortage in urban areas are among the numerous socio-economic challenges that need to be addressed.

The availability of natural resources also plays a key role. Sunshine and thorny bush (the latter in central parts of the country) are abundant, while freshwater is rare and precious. Finally, Namibia hosts significant populations of plants and animals (biodiversity) that are important from conservation, environmental stability, and tourism perspectives, which should not be sacrificed for energy, ‘green' or otherwise.

Are coal and fossil fuels dying?

Due to the strong link between the use of fossil fuels and climate change, there is pressure on governments worldwide to find alternatives to coal and oil. These sources of energy also contribute to air pollution, which can lead to health issues for individuals residing near power plants and in urban areas with high concentrations of fuel-burning vehicles. The global shift away from these ‘dirty' sources of electricity is a positive development, but Namibia must be cautious in its approach to transitioning to cleaner energy, ensuring it aligns with its own developmental needs.

Currently, Namibia imports coal, diesel, petrol, and other fuels to produce electricity and power the transport sector. The price of oil is determined on a global level, which puts Namibians at the mercy of geopolitical issues that cause spikes in the oil price. Reducing the nation's reliance on imported coal and fuel derived from oil is a good idea for both environmental and developmental reasons.

Our conclusion: move away from coal and oil imports as soon as practical.

Will oil exports benefit all Namibians?

Although oil imports should be reduced as much as possible, Namibia could become an oil exporter. Recent explorations off the coast of Namibia have sparked hope among many, with several major oil companies showing interest in exploiting these deposits. While joining the ranks of oil-producing nations goes against global pressure to move away from fossil fuels, it is hard to argue that Namibia should not be allowed to exploit this highly valuable resource. This is especially true when wealthy, industrialised nations that have caused the current situation and have benefited for decades from this resource continue to exploit fossil fuels in their jurisdictions.

The potential costs to the local environment are nonetheless worth noting—oil spills, while rare, can be catastrophic for marine life. Water pollution and possible impacts on commercially important fish stocks must be taken into consideration. On the positive side, the large multinational oil companies showing interest in Namibia are aware of how to mitigate these impacts and are subject to global scrutiny to maintain good environmental practices. Potential oil spill mapping and response plans are part of each EIA for oil exploration, and Namibia has an oil spill disaster management plan in place, working with the oil exploration sector, neighbouring countries, the international community, and local NGOs.

The current discussions surrounding oil focus on local content policies and contracts to mandate Namibian ownership and create jobs, yet this is a distraction from more pressing issues. The nature of the industry is such that relatively few local jobs should be expected, while local ownership clauses are likely to benefit a few well-connected individuals rather than the whole country. If managed this way, economic inequality is likely to increase, and we can expect Namibia to come under the ‘resource curse' that plagues several other oil-producing countries.

If the government receives about US$20/barrel of oil produced, it could nearly double current tax revenues. The real question that all Namibians should be asking is how this massive budget expansion will be used. Namibia needs to learn from oil-rich countries that have generated widespread, long-lasting, sustainable benefits from oil revenues (e.g., Norway and its sovereign wealth fund) and apply these ideas at home. A long-term fund that provides proper housing and sanitation for the urban poor, invests in excellent education and healthcare, builds a strong, diversified, and resilient economy, and invests in the environment and sustainable practices (among other priorities) would be more useful than granting a few local elites ownership over oil production companies.

Conclusion: focus more on benefit sharing than ownership issues. The government has a poor track record in this regard. A national focus, transparency, accountability, and robust institutional structures are necessary to ensure the wise use of oil revenue.

Powering a dry country with fresh water?

Namibia's biggest local source of electricity is the hydroelectric power plant at Ruacana Falls on the Kunene River. The amount of electricity produced is dependent on water flows, which are in turn affected by multiple environmental (e.g., drought) and human (e.g., water extraction upstream) factors.

Another hydropower dam is planned on the same river downstream of Epupa Falls near Marienfluss. The environmental and cultural impacts of such dams can be high, while the amount of energy produced could be highly variable. Climate change predictions suggest that we should prepare for longer and more severe droughts. Meanwhile, river flow models predict an overall decline in river water volume of 25-35% due to climate change. It is therefore likely that the reliability of electricity produced from hydropower will decline in the future.

Conclusion: Given the high negative impacts of dams and the reduced reliability of hydropower, this is not the best option for Namibia, as there are better alternatives.

Are there drawbacks to solar and wind?

The abundant sunshine across Namibia and windy conditions on the coast appear to be the solution to all energy woes, but this is not entirely true. Solar farms and wind turbines can play a supporting role at a local level (e.g., powering a mine or shopping mall) or by contributing to the electricity grid. Even more so than hydropower, however, these sources are intermittent. Even with Namibia's brilliant blue skies, the sun always sets. Wind is even less reliable than sunshine—even Lüderitz has calm days.

The key challenge for these intermittent forms of energy is storage. Battery technology is constantly improving, but it remains a critical limitation that prevents solar and wind from entirely replacing energy from conventional power plants. Solar panels and the current batteries used for these systems require rare earth minerals, thus increasing the demand for mining. Procuring rare earth minerals and manufacturing solar panels have been respectively linked with child labour in the Democratic Republic of Congo and slave labour in China, as well as severe environmental degradation and radioactive contamination from the thorium that is always associated with rare earths.

After 25-30 years, panels and turbines become so inefficient that they must be replaced, yet it is difficult and expensive to recycle them. Wind turbines incur an additional environmental cost for birds and bats that become entangled in their blades, making them a less attractive option for development near important bird areas. Wind turbines may also detract from the natural beauty of a particular landscape, thus affecting tourism if they are built in tourist hotspots.

Solar farms have fewer drawbacks than wind turbines, since they can be built anywhere that gets sufficient sunlight (most of inland Namibia). Parts of southern Namibia that are becoming less suitable for livestock due to frequent droughts would be ideal for solar farms. If the solar farms are located on the southern communal lands, the communities living in these areas would become shareholders in these operations, thus generating jobs and income.

Conclusion: Solar power can make a significant contribution to Namibia's energy needs, particularly when combined with a strong and reliable baseload generation.

Green hydrogen: smoke and mirrors?

Green hydrogen has been introduced to Namibians as a highly profitable idea that is expected to create 250,000 jobs, at a time when the economy is struggling and unemployment rates are high. Yet the basis for these claims is flimsy, given what we know about hydrogen as a source of energy. Hydrogen has been explored in many countries as a potential source of power, but it has proven to be inefficient, expensive, and challenging to store. Green hydrogen, in particular, is prohibitively expensive compared to using normal electricity or fuel.

As a result of these technical and economic issues, global enthusiasm for hydrogen is waning. In July 2025 alone, over US$16 billion in potential investment in hydrogen production and use projects was withdrawn from the sector, as major hydrogen projects were cancelled or shelved. Since then, BP has cancelled its US$36 billion investment in renewables and green hydrogen in Australia, and the EU has fallen far behind its planned green hydrogen production and import targets of 10 million tons each, with the gap between ambition and reality widening, and only 17% of these targets likely to be achieved by the end of this decade.

Germany, which is a key player in the Namibian hydrogen sector, has also recently halted several green hydrogen projects. Plans to convert two steel plants in Germany to use hydrogen were cancelled as the developer realised the huge costs associated with using hydrogen rather than other forms of energy and handed back €1.3 billion in subsidies. A German energy company has reportedly withdrawn from its agreement to purchase green ammonia from the Hyphen project.

From a Namibian perspective, it is unlikely that the green hydrogen sector will generate significant employment opportunities or yield sufficient profits to generate tax revenue. Relatively small hydrogen projects that aim to produce green hydrogen and ammonia as a fuel for shipping (possibly the most sensible use of hydrogen) could create a few jobs and generate minor taxable revenue, but are unlikely to occupy more than a small “niche" in the carbon-neutral energy mix.

By contrast, the large-scale hydrogen-ammonia plans in southern Namibia, slated to supply steel plants in Germany, are likely to come at an immense environmental cost while producing something that steel plants will not buy. The Namibian government should not invest any taxpayer money in this plan for economic reasons, and should not proceed with it for environmental and human rights reasons.

Conclusion: Expectations for green hydrogen in Namibia are significantly overstated and do not align with global market realities. It plays a very small role in Namibia's energy future.

Bush biomass: Deforestation or Sustainable Energy and Restoration?

The dense thickets in the central regions of Namibia reduce farm productivity in this area and have long been considered an ecological problem to be addressed. It reflects rangeland degradation resulting from poor farming practices, including wrong grazing systems and the exclusion of fire. In a recent development, the bush (an indigenous woody pioneer invader species) is being viewed as an economic opportunity for the energy sector. Namibia hosts an estimated 1.5 billion tonnes of standing woody biomass, approximately 30% of which could be harvested sustainably and in a carbon-neutral manner. There is growing evidence that restoring bushy rangelands to open savanna ecosystems is not only beneficial for productivity and biodiversity, but also for water infiltration and soil carbon sequestration.

This biomass can be used to produce electricity for Namibia's domestic use and be exported as charcoal, a form of green energy, to other markets. Domestically, NamPower is constructing a 40MW power plant near Tsumeb, which will convert bush into electricity and supply the national grid. For export, the SteamBioAfrica project is exploring ways to convert biomass into a cleaner-burning, ‘green' coal that can be sold to European markets. When biomass is superheated, it produces biochar, which is known to improve soil structure and productivity, thereby restoring degraded rangeland soils.

The labour-intensive nature of bush harvesting and processing means that these biomass businesses could create more jobs in rural areas than farming alone. The industry also creates space for entrepreneurship, as there are many potential uses for bush that have yet to be explored.

Conclusion: Bush biomass presents an economic opportunity and a potential contributor to Namibia's domestic energy mix and exports, with numerous potential environmental benefits.

Going nuclear—is it feasible, and how would we do it?

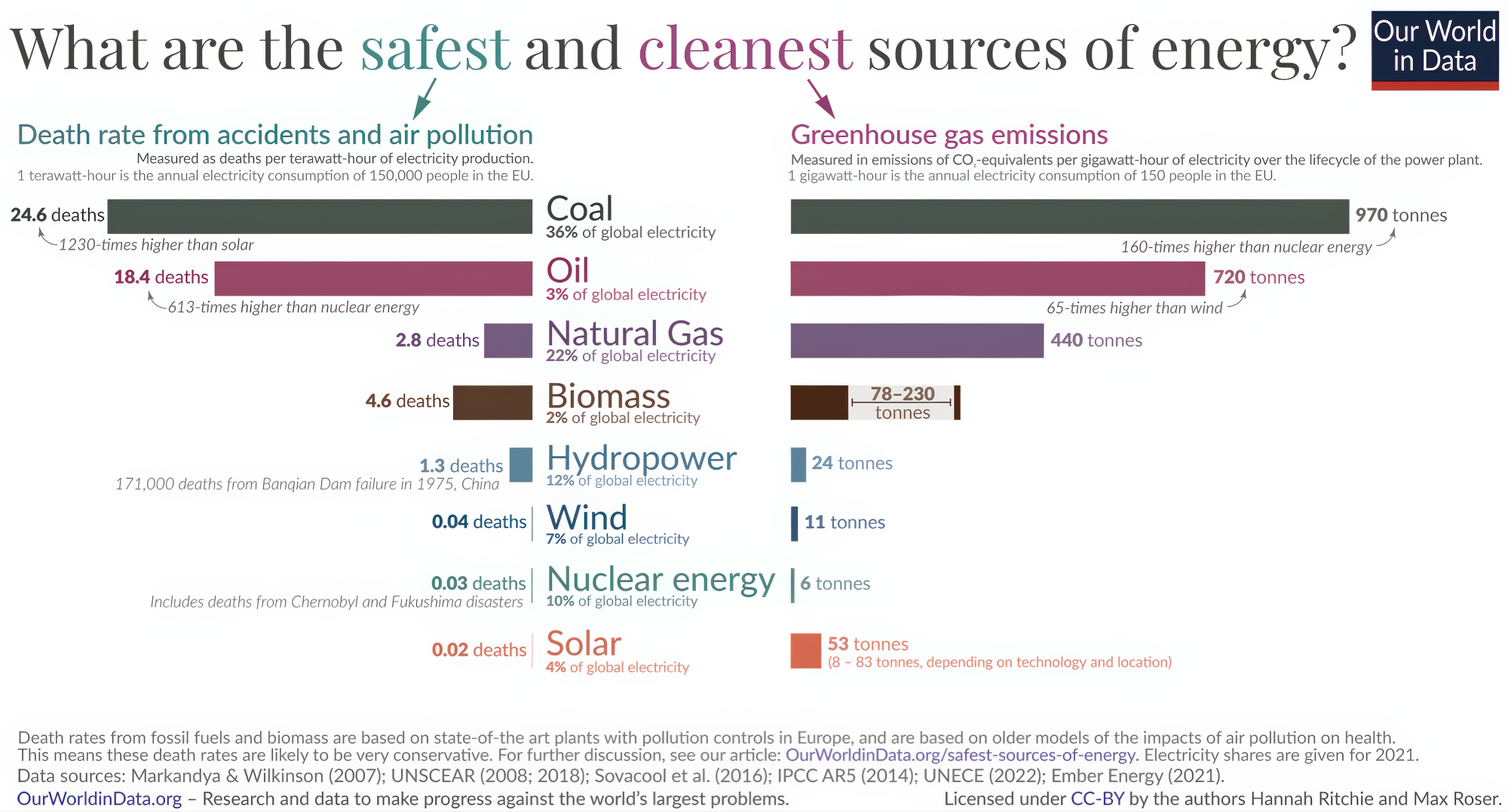

Nuclear energy is one of the cleanest forms of energy, with even lower greenhouse gas emissions than solar and wind power when the whole system is taken into account (e.g., production and disposal of materials, known as cradle-to-grave). Contrary to popular opinion, nuclear energy is also safe—besides a few well-publicised disasters caused by earthquakes (Fukushima, Japan) and accidents at outdated facilities due to human error (Chernobyl, Russia)—when measured as the number of deaths per terawatt-hour of energy produced globally, nuclear safety is comparable to wind and solar. The 820 deaths in the coal energy sector and 613 deaths in the oil energy sector, for each death in the nuclear energy sector, are seldom publicised.

Due to its high energy content, the environmental footprint of nuclear energy, including mining, enrichment, power plant operations, and waste storage, is relatively small compared to most other energy sectors, particularly renewable energy and, in particular, green hydrogen. For example, the Torness Nuclear Power Station, just 52 km from Edinburgh, Scotland, surrounded by small farms, produces twice Namibia's peak electricity demand on just 20 hectares. Another major consideration is that nuclear energy does not require backup energy sources that are essential for renewables. When the sun does not shine, and the wind does not blow, expensive back-up options need to be on standby, such as gas-powered facilities. These backup generators and their associated running costs are seldom factored into the energy costs provided by proponents of renewable energy.

Disposal of nuclear waste remains a challenge that is continually being improved through research and engineering. It is now possible to reuse nuclear rods multiple times, reducing the amount of waste produced. Since some nuclear waste products are radioactive, they must be stored in a safe container for extended periods. However, with ever more effective reuse, the amount of waste that needs to be stored is largely reduced. The best current options for storage are deep underground containers in seismically stable, sparsely populated areas.

For Namibia, the key hurdle to overcome for developing a nuclear power plant is investment. The initial capital requirements are high, and it would make sense to develop a plant with co-investment from other governments and private financiers. Other hurdles include the current lack of local expertise in the nuclear field and an inadequate legislative framework; however, with proper planning and commitment, these too can be overcome.

The size of Namibia's grid is another obstacle if a conventional nuclear power plant were to be considered. However, the current trend to develop small modular reactors (SMRs) will also allow countries with a small grid, such as Namibia, to utilise nuclear energy. SMRs could indeed become a game changer across the entire continent of Africa.

Given the similar electricity situation of Botswana and Namibia, we suggest that Botswana is an ideal government partner. The electricity produced by a relatively small (covering 20 hectares) nuclear power plant is sufficient to meet the demands of both Namibia and Botswana, and to be exported to neighbouring countries. Both countries would become independent of the South African electricity supply and be able to reduce electricity costs for their people.

Nuclear power plants require substantial amounts of water to maintain their cooling systems at an optimal temperature for operation. Suitable locations for a Namibian powerplant are therefore limited to the coast (using desalinated water), near one of the perennial rivers in the north or south, or next to Namibia's largest and currently unused dam: Neckartal. Each of these options should be explored during a thorough, fully consultative feasibility study.

Conclusion: Nuclear power is a promising medium- to long-term solution for Namibia's domestic energy needs and is likely to enable the country to become a net exporter of carbon-neutral electricity.

Integrating energy solutions with water and agriculture

The development of nuclear base-load energy, integrated with the Ruacana hydropower plant, the new biomass plant near Tsumeb, and other existing power sources, would provide a consistent source of energy (base load) that increases the amount of solar energy the grid can support. Increasing solar power supply without a strong base load can lead to grid instability and subsequently higher consumer costs. A reliable and resilient national energy system is crucial to attracting foreign investment and driving Namibia's economic growth.

A further requirement for economic growth is secure water. The Okavango and Zambezi River systems face the same limitations as the Kunene – a 25 to 35% reduction in flow due to climate change and increasing upstream demands for water for irrigation and urban development. Building Namibia's water future on these river systems is a high-risk and short-sighted approach.

Rather, we could utilise our proposed integrated nuclear, hydro, biomass, and solar energy system to desalinate seawater for use in the central coastal regions and pump it to central Namibia. As with the nuclear partnership, Namibia could work with Botswana on desalination and pumping. Once water has reached Windhoek, it can be gravity-fed most of the way to Gaborone, the capital of Botswana. This water development would allow both countries to expand their high-value crop production in suitable locations along the new pipeline.

Final thoughts

In the near future, Namibia should aim to transition its domestic energy use from imported coal and fuel to a mix of nuclear and renewable energy sources, guided by an integrated energy policy and strategy, working in collaboration with Botswana. The most promising and environmentally-friendly options are existing hydropower, bush biomass, solar power, and nuclear. This makes more sense than destroying a national park and its biodiversity for high-risk, high-cost, no-gain “green" hydrogen for Germany and other parts of Europe. We should prioritise Namibia's energy needs first, while retaining export options with our surplus energy.

In our proposed scenario, Namibia's electricity would be almost entirely carbon neutral. Surplus energy could be sold to the Southern African energy grid, helping the region meet its energy needs and reduce its carbon footprint. It could also be used to produce carbon-neutral hydrogen and ammonia, which can be sold to industrialised countries that may still wish to purchase such energy.

In terms of energy exports and revenue generation, offshore oil, nuclear power, solar, and bush biomass are the best options. The exploitation of marine oil deposits, if proven commercially viable, must be carefully managed to limit environmental impacts and maximise broad-based economic benefits. By investing in nuclear power, biomass, and solar energy, Namibia will position itself as a long-term exporter of carbon-neutral energy while supplying its domestic needs at an affordable rate for its citizens.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.