Balancing livelihoods and sustainable fisheries management

12th November 2025

12th November 2025

For centuries, conservation and capitalism have been framed as opposing forces. Today, however, a new paradigm is emerging: ecological protection is being recognised as the foundation of long-term prosperity. The central issue, especially for marine environments facing overfishing and declining fish stocks, is whether true economic resilience can be achieved only through sustainable ecosystem management.

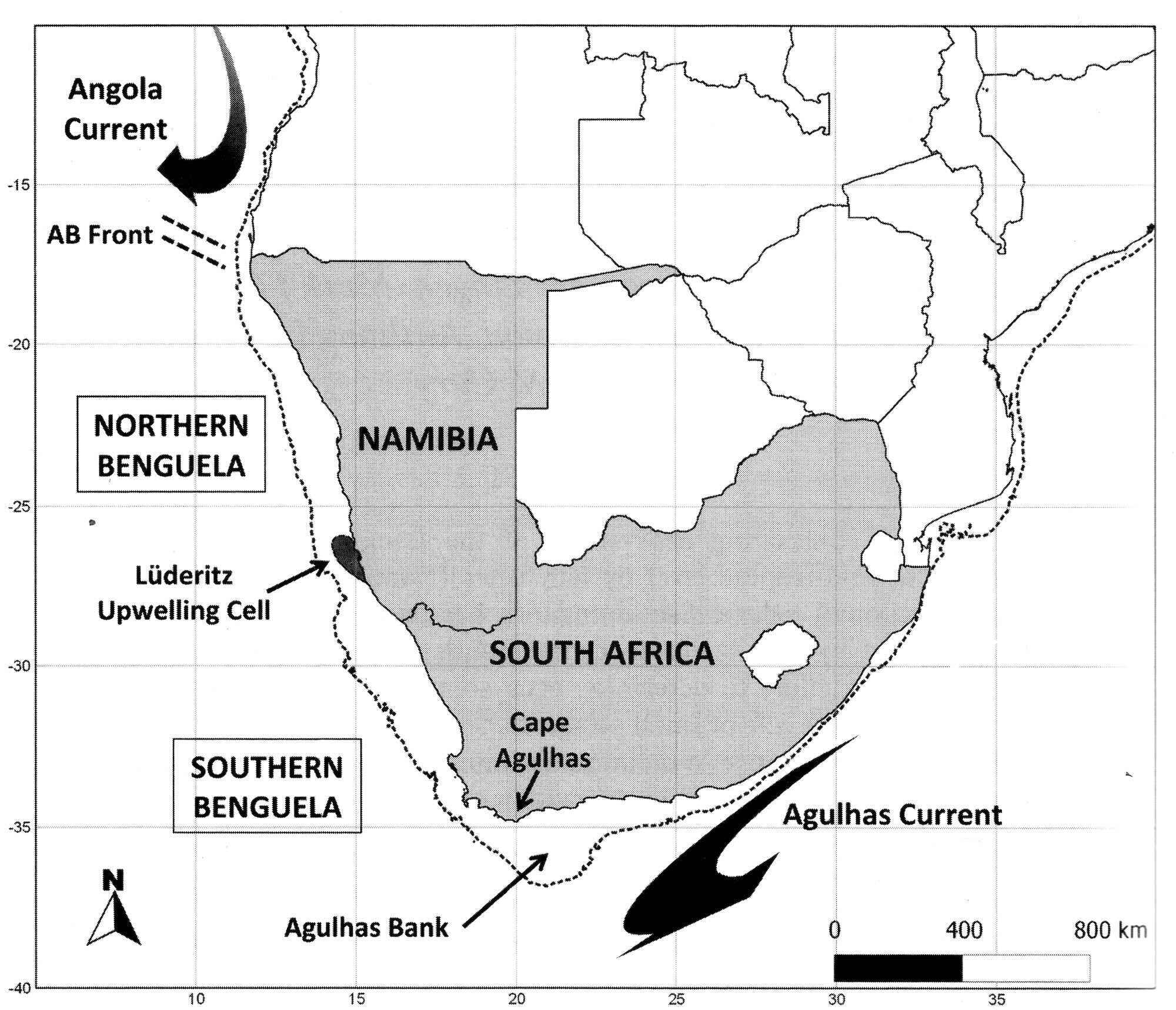

In the 1950s and 60s, the rich Benguela Current ecosystem formed the backbone of the pilchard (also known as sardine) industry, with an estimated biomass between 4 and 11 million tonnes in the northern Benguela ecosystem off Namibia. Fishing efforts there peaked in the late 1960s, but declined rapidly from the early 1970s as pilchard stocks collapsed. By 1980, eight of the 11 pilchard canneries had closed, with upwards of 3,000 jobs lost. Fishing efforts in Namibia continued to sustain the pilchard industry, albeit at extremely low levels, but pilchard stocks failed to recover.

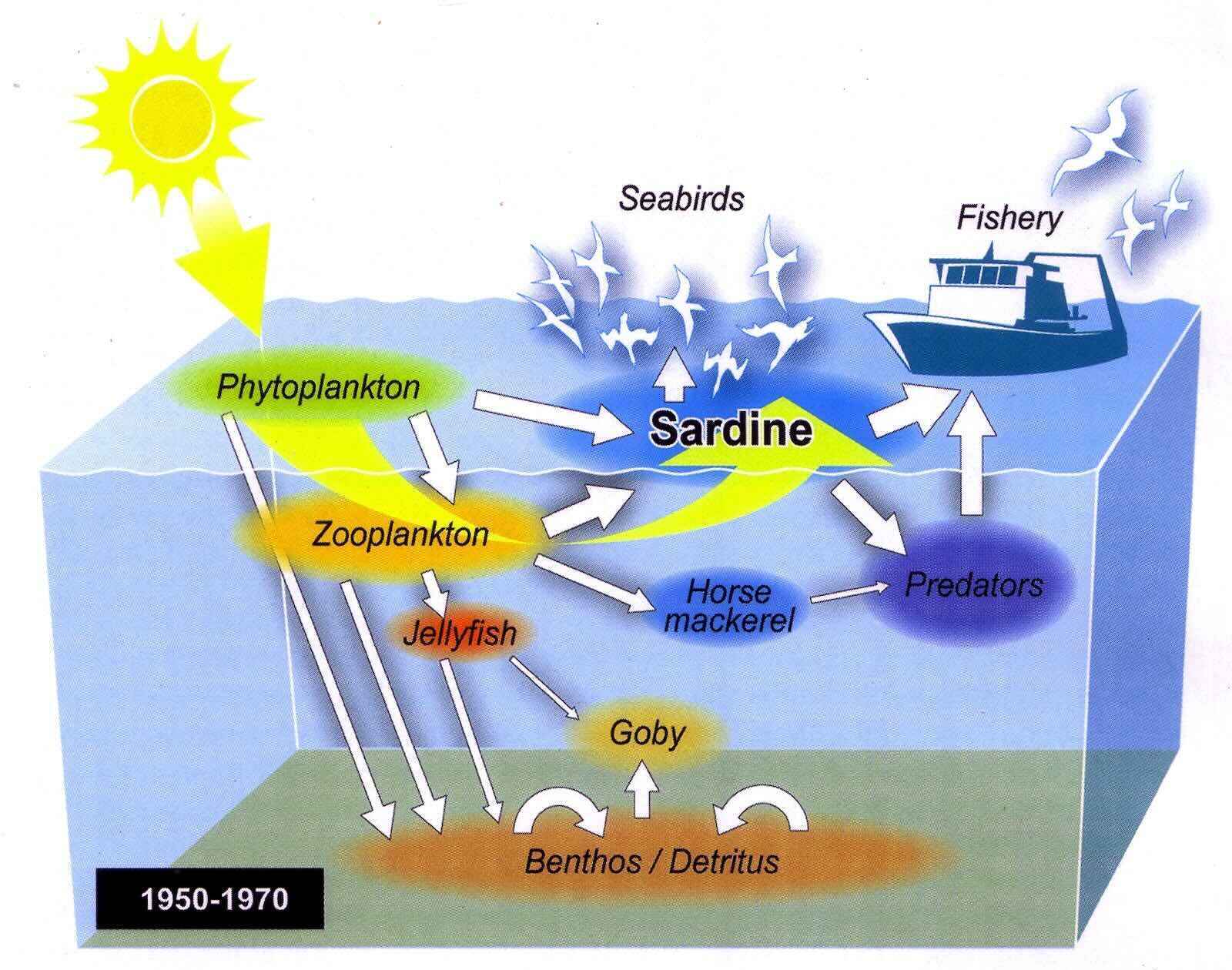

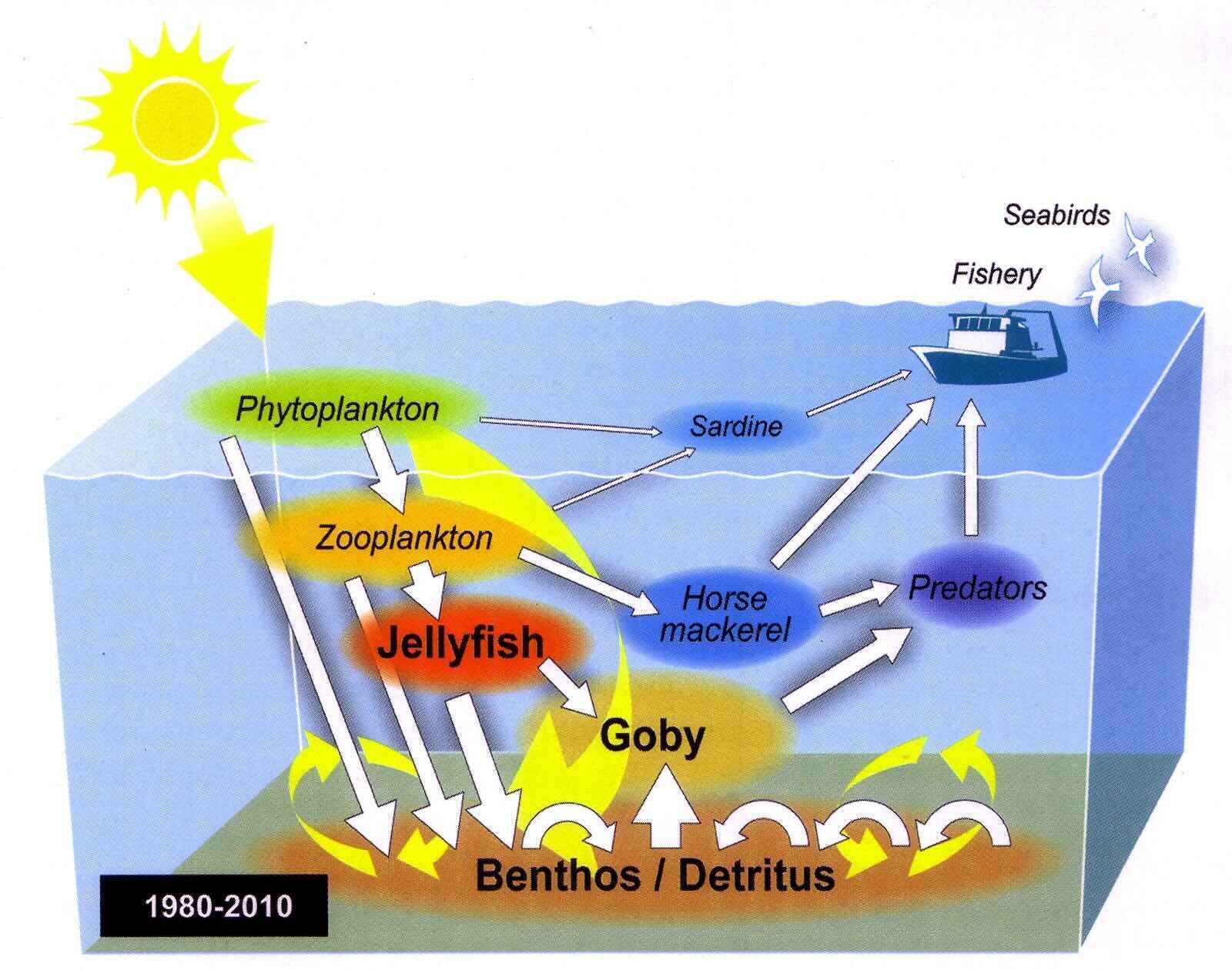

This article highlights the importance of maintaining a healthy marine ecosystem, which is critical to ensuring that an equilibrium amongst diverse species – from minute plankton to fish to top predators such as seabirds – is maintained. The collapse of a keystone species has the potential to disrupt the Benguela Current ecosystem, leading to an unhealthy state with repercussions not only for top predators but also for people and livelihoods.

Namibia and South Africa are struggling to strike a balance

Recognising the severity of the collapse and its repercussions on the health of the northern Benguela ecosystem, Namibia introduced a moratorium on pilchards in 2018, with the benchmark for reopening set at one million tonnes of biomass and fish of two or three year classes represented, a cautious target aimed at stock recovery. Yet in July 2025, the Cabinet authorised a quota of 10,000 tonnes, despite scientific advice and without transparent evidence that the benchmark had been achieved.

While the decision reflects real socio-economic pressures, including high unemployment and industry lobbying, it raises questions about transparency and consultation: Which stakeholders were involved in shaping this outcome? How were the competing needs of industry, small-scale fishers, and conservation weighed? The process itself remains opaque, leaving observers concerned that short-term expediency may again override long-term sustainability.

Across the border, South Africa provides a case that followed a different trajectory. In March 2025, BirdLife South Africa and the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds (SANCCOB) won a landmark High Court ruling compelling the government to enforce year-round no-take zones around six African Penguin breeding colonies. These zones directly restrict pilchard and anchovy fisheries in areas of critical ecological overlap. The ruling mandates annual reviews through 2035, embedding accountability and transparency into policy. This approach demonstrates how governance mechanisms – legal challenge, judicial oversight, and stakeholder mobilisation – can create structured processes that balance industry activity with ecological imperatives.

The South African experience illustrates the importance of holding the line until genuine recovery is secured and soundly documented. For conservationists, the case has emerged as a critical inflection point, demanding unwavering commitment to prevent species extinction.

Namibia's challenge is not the absence of protection measures, but how these are implemented and enforced. Since 2009, the Namibian Islands' Marine Protected Area (NIMPA) has safeguarded critical breeding and foraging grounds for African Penguins, Cape Gannets, and cormorant species through zoned management that restricts a range of activities, including fishing.

On paper, this represents one of the strongest conservation commitments in Africa. Yet MPAs cannot function in isolation. The productivity of NIMPA depends on the health of the wider northern Benguela system, particularly the recovery of pilchard stocks that seabirds and fisheries alike rely upon. Without effective regional management to ensure pilchard biomass targets are reached and sustained, the protections offered by NIMPA risk becoming negligible. In other words, protecting one particular area cannot offset unsustainable harvest decisions that affect the whole Benguela ecosystem.

Ultimately, governments across the Benguela Current system face the same difficult balancing act: safeguarding marine ecosystems while supporting jobs, food security, and economic growth. In Namibia, where unemployment remains high, pressure to reopen the pilchard fishery is understandable in the short term. This tension is illustrated by the Secretary of Benguela Infinite Fisheries & Harvesting Association in Lüderitz: “…some days, our fishermen go out and there is nothing for them to catch. As an association, supporting over 200 members, our fishermen need to be able to access key fishing areas".

Conservationists warn of species extinction if stocks fail to recover; industry seeks to keep canneries viable; government faces intense pressure to stimulate employment. The central question remains whether lifting the moratorium now will deliver short-term relief at the cost of undermining long-term recovery – and with it, the very resource base that Namibia's people and economy ultimately depend upon.

Is history repeating itself? The Namibian experience serves as a cautionary tale: delaying decisive action can deepen ecological collapse and amplify socio-economic consequences. The lesson is clear. Protective measures, however unpopular in the short term, can safeguard both biodiversity and the long-term viability of fisheries.

The dire state of the Benguela Current Ecosystem

Two recent scientific reviews of food limitations for seabirds in the Benguela Current ecosystem, one by Jean-Paul Roux and colleagues in 2013 and another by Robert Crawford and colleagues in 2022, stressed that safeguarding keystone species such as pilchards is critical for the survival of many other species. Top predators like the African Penguin, Cape Gannet, and Cape Cormorant are in severe decline primarily due to the lack of good-quality fish.

These articles argue: 1) a clear correlation between decline in pilchards and reduction in breeding success among endangered and critically endangered seabirds, and 2) that the increased abundance of jellyfish can be attributed to the collapse of pilchards within the Benguela Current ecosystem. This underscores the fundamental link between forage fish abundance and the viability of higher predators in the system, as depicted in the images below.

As demonstrated by Namibia and South Africa, there are multiple ways to safeguard such keystone resources. Spatial measures include South Africa's no-take zones around certain areas and Namibia's no-take zone for some species from the coastline to 200 metres water depth (known as the 200m isobath). According to Matti Amukwa, Chairperson of the Namibian Fishing Confederation, “The 200m isobath restrictions were introduced for scientific reasons. The shallow waters are the spawning grounds for most of the commercial species in Namibia" (as quoted in the New Era, 2022). There is also an important role for protected areas such as NIMPA or other habitats or ecosystems that are crucial for the structural and functional health of a marine ecosystem, such as “Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas" (some of which may be transboundary), provided they are carefully designed and well managed.

Temporal measures include well-enforced species-specific fishery moratoriums or seasonal closures (as is the case for hake and rock lobster in Namibia), while other management actions, apart from a robust, transparent quota system based on solid scientific data, may include fishing gear restrictions or bycatch limitation measures. Such initiatives, provided they are effectively implemented, monitored, and regularly assessed, have been widely documented to restore near-extinct species, safeguard key habitats and ecosystems, rebuild and increase fish stocks, and provide refuge for threatened species.

Working towards a common goal

Marine conservation and fisheries management cannot succeed in isolation; they must work together, or we risk losing both biodiversity and livelihood opportunities. At this point, the stakes could not be higher: critically endangered seabirds teetering on the brink of extinction and crashed pilchard stocks that struggle to recover are clear signs that the Benguela Current system is unwell. Unless this situation improves, we will face devastating long-term socio-economic consequences for communities that rely on the fishing industry.

Are we doing enough to safeguard our resources while ensuring the fishing industry can benefit sustainably? Strategic, well-informed interventions, including well-designed and monitored no-take zones, buffer areas, and temporal closures, offer a clear path forward. Namibia's 2018 pilchard fishery moratorium demonstrates the power of foresight: temporary sacrifice today can yield thriving stocks tomorrow. Similarly, initiatives such as the Benguela Current Convention (BCC) and the NIMPA+ project show that collaboration between governments, conservationists, and industry is not just possible, it is essential – at local, national, and international levels.

The lesson is undeniable: protecting marine ecosystems is not a zero-sum game. When approached strategically, conservation safeguards biodiversity, sustains fisheries, and strengthens coastal economies. The time to act is now. If we seize this moment, we can ensure that southern Africa's rich marine resources continue to support both nature and people for generations to come.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the Executive Committee of NAMCOB for their input and Dr. Jean-Paul Roux for his valuable insights, contributions, and permission to use images from his studies.

Further Reading:

Crawford RJM, Sydeman WJ, Tom DB, Thayer JA, Sherley RB, Shannon LJ, McInnes AM, Makhado AB, Hagen C, Furness RW, Carpenter-Kling T, and Saraux C (2022). Food limitation of seabirds in the Benguela ecosystem and management of their prey base. Namibian Journal of Environment 6A: 1-13. https://doi.org/10.64640/ft3yd661

Roux J-P, van der Lingen CD, Gibbons MJ, Moroff NE, Shannon LJ, Smith ADM, and Cury PM (2013). Jellyfication of marine ecosystems as a likely consequence of overfishing small pelagic fishes: Lessons from the Benguela. Bulletin of Marine Science 89(1):249–284. https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2011.1145

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.