Snakes in the City – the Windhoek Experience

10th August 2020

Ever had a dangerous-looking snake slither into your home, car or garage? You want to remove it, but don’t like the idea of killing snakes, yet you’re also not keen on a trip to the hospital if it bites you. Who do you call? The snake-busters! More officially known as Snakes of Namibia, a non-profit organisation established in Windhoek, Namibia in 2013 to assist people and snakes when they have unwanted encounters.

We remove snakes safely (for both parties) and raise awareness about their ecological importance. During the last seven years, we have successfully removed a thousand snakes from residences across the city, while our outreach programme has educated over ten thousand Namibians on snake safety and conservation.

While removing snakes is part of our daily lives at Snakes of Namibia, we want to investigate this issue further. Human-snake conflict is a form of human-wildlife conflict that remains understudied, even though the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that over 500 000 people are envenomated (bitten) every year on the African continent, leading to death or long-term disability. Even this figure is likely to be an underestimate of the true impact of snakebite, as very little data are available from public hospitals. In recent years more scientists have studied the impact of snakebites, yet very little work has been done to find a solution to human-snake conflict. We would like to reduce the number of potentially deadly human-snake encounters in Windhoek by understanding and addressing the underlying drivers of human-snake conflict. When it comes to snakebites, prevention is much better than rushing to hospital for anti-venom – believe me!

In 2015 Snakes of Namibia joined forces with the Namibia University of Science and Technology’s Biodiversity Research Centre (NUST-BRC, read more about their work here) to use our snake removals data to delve deeper into human-snake conflict in the city. Each time we remove a snake, we record our location, the snake species and its sex. We have used the resulting data from the last three years to investigate snake occurrences in the city, the frequency of human-snake conflict in different areas, and to assess snake movement trends over time and during different seasons. This information could help researchers predict where future conflict incidences may occur while also helping us better understand snake distribution and diversity in the city of Windhoek.

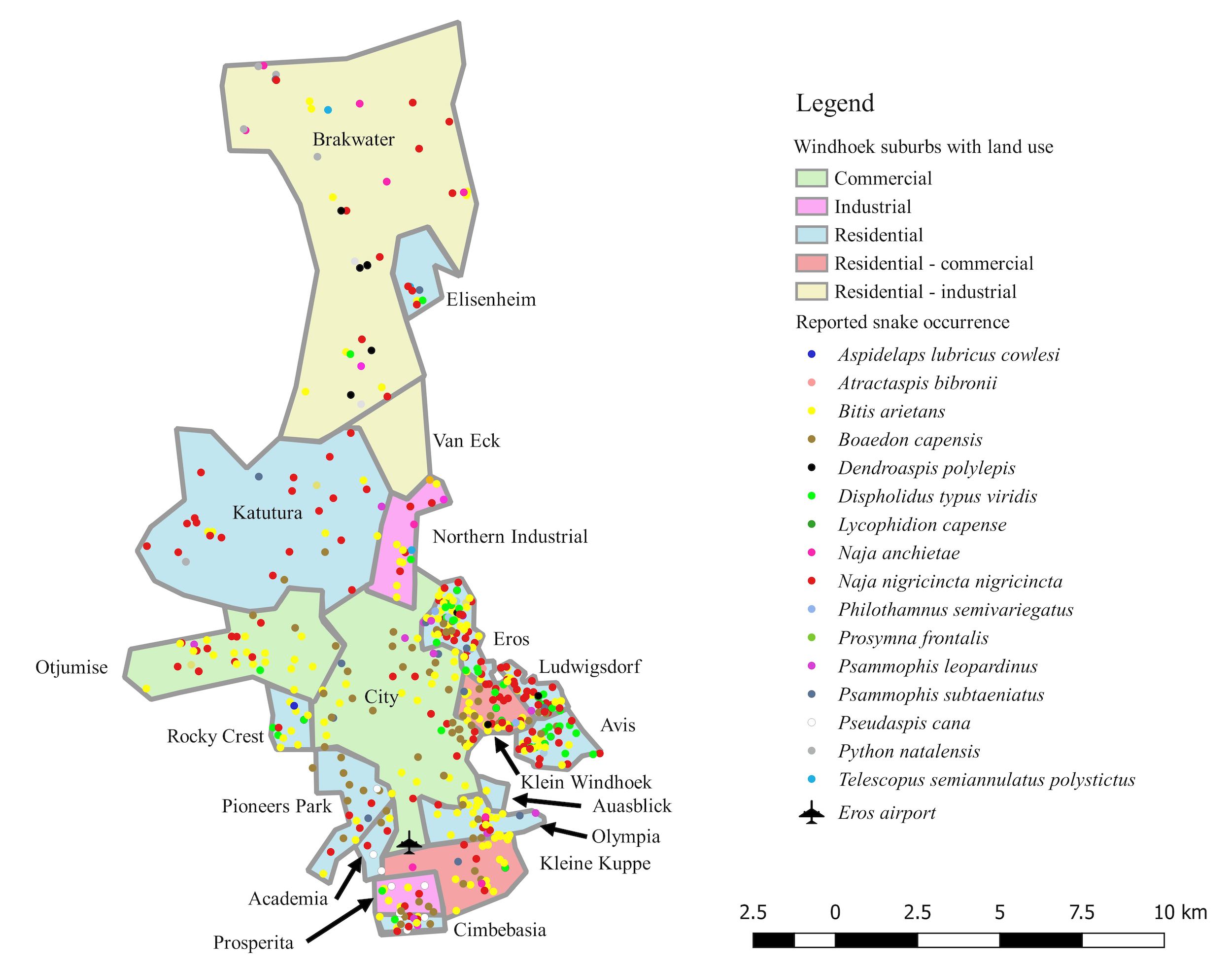

Between August 2015 and July 2018, we removed 509 snakes representing 17 different species from residential areas; 80% of them were dangerous enough towards humans to be of medical importance. Yet no one was bitten prior to calling us or during the removal process. Puff adder (163 individuals) and zebra snake (135) removals combined accounted for 60% of all snake removals. The brown house snake (57) and boomslang (52) were the next two most common species removed.

Interestingly, 62% of the snakes we removed were female while only 38% were male, although puff adders were the exception to the rule with more males being removed. It seems that the females were looking for nesting sites near or in buildings, while the males were roaming around looking for potential mates.

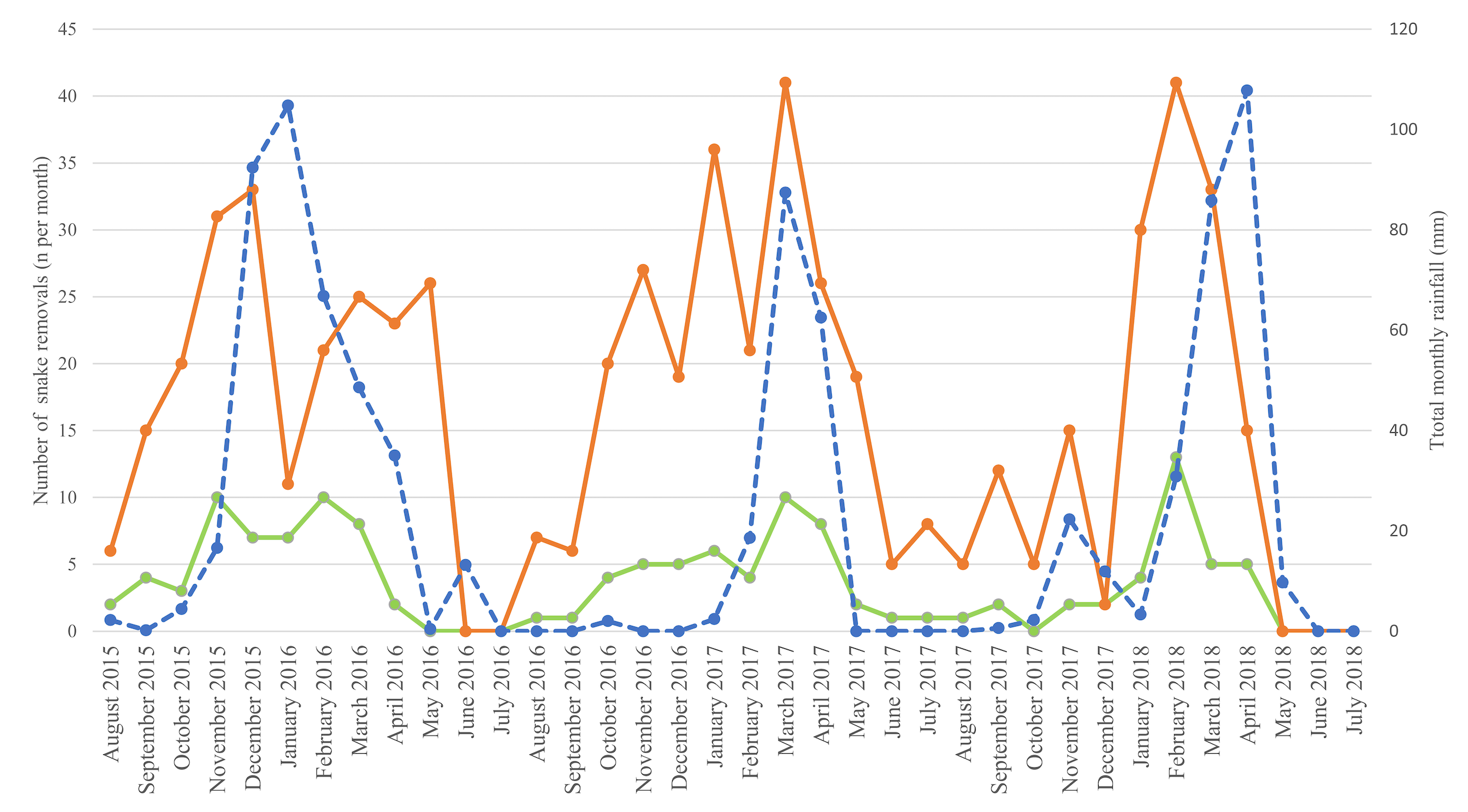

The numbers of snake removals are highest during the wet season and lowest in the dry season of each year (see Graph below). Puff adders seemed to be the first species to respond to increasing humidity, as removal rates increased even before the rains came. Zebra snakes showed a similar pattern, while removals of other species peaked in the late rainy season. Many snake species become inactive during times of severe drought due to food scarcity and will start moving around again after good rains that lead to increased prey availability. During heavy rains, flood risk forces snakes to seek higher ground and possibly land up in a house or garage as a result.

The areas of Windhoek that reported the highest number of snake conflict incidences were Eros (62 snake removals), Klein Windhoek (57), Ludwigsdorf and Avis (40), Brakwater (36) and Elisenheim (31) while other suburbs reported 20 or fewer removals each (see Map below). The most affected suburbs are in higher income areas, which may be due to the well-irrigated gardens in these areas that provide snakes with sufficient shelter, water and food. However, it is also possible that many people in the middle and lower income areas are not aware of the snake removal service Snakes of Namibia offers and therefore do not call for our help. The number of removals in the southern suburbs increased somewhat in the study period due to the construction of new roads and housing complexes that may have disturbed snakes that otherwise would not have caused any incidents.

There are currently no management strategies to address human-snake conflict in Namibia; we aim to rectify this situation. This study and others will help us understand their movement patterns and environmental preferences, which we can use to minimise the risk of snakebite by creating and implementing a management strategy. This information will also help medical practitioners gauge how much anti-venom from which species they should keep in stock. Finally, our data can be used to make better decisions about the expansion of Windhoek to reduce the city’s impact on our unique biodiversity.

Our published study on snake removals is only the beginning of Snakes of Namibia and NUST-BRC’s joint research plans. We are currently investigating the effects of translocation on zebra snakes by attaching tracking devices to some of the individuals we remove from residential areas. This study aims to improve our understanding of the long-term benefits or problems relating to snake translocation to reveal whether or not translocation helps to conserve this species. We are also planning a genetic study on the zebra snakes we remove to determine whether or not these individuals are related to each other. For updates on the results of these efforts, watch this space!

Reference: Hauptfleisch, M.L., Sikongo, I.N. & Theart, F. (2020) A spatial and temporal assessment of human-snake encounters in urban and peri-urban areas of Windhoek, Namibia. Urban Ecosyst. doi.org/10.1007/s11252-020-01028-9

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

The NUST Biodiversity Research Centre produces quality trans-disciplinary research to support data-driven decision-making for wildlife management and conservation. We welcome school learners who are considering a career in biodiversity or conservation field to visit the centre. The post-graduate students will gladly demonstrate their work and share their experiences. Like us on Facebook to stay up to date with our research projects.

Francois Theart is a natural resource management student at NUST with a passion for herpetology. His passion for snakes started at the age of 13 when he had his first snake encounter. He started removing snakes a year later and has dedicated his life to snake conservation ever since.

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.