Brandberg Lion Attack

A minor drama in a complex conservation landscape

5th April 2021

Sometime after 11 O'clock at night, I am abruptly woken from deep sleep. My wife, Irene, suddenly sits up next to me. I also sit up and through the mosquito gauze of our tent door see an animal facing us in the moonlight, perhaps five metres away but partly obscured by a knee-high shrub. I think it's an inquisitive spotted hyaena. The animal only looks at us for a short moment, then fades into shadow as it walks towards and past the side of the tent. There it turns, pauses – and attacks with a chilling growl.

We were camping on the western side of the Brandberg on Friday 23 April 2021, having arrived at sunset after a long drive from Windhoek. Namibia's highest mountain lies in the Tsiseb Conservancy, one of the southernmost of around 40 adjoining conservancies that make up the Erongo–Kunene Community Conservation Area. The conservancies reach from the Kunene River to the Swakop River, and from the Skeleton Coast Park to Etosha National Park. We had positioned our sturdy 2.5 x 2.5 metre canvas tent between our Land Cruiser, standing in the well-worn access track, and a small koppie with steep basalt walls. It was a warm night and we had kept the canvas door and two side windows rolled up. The door faced west, while one window looked onto the Cruiser and the other onto a rock wall, which cast a dark shadow in the soft moonlight. Sitting on Irene's left, I could only see the dark patch of rock, less than two metres away through her window.

Irene sees the animal turn and charge at her. She instinctively screams at it at the top of her lungs. I immediately also shout as loud as I can. I'm half expecting a typical lunging, swiping hyaena bite at its target – in this case Irene's face at the window – but our screaming makes the animal veer away out of sight. I lean back and take the revolver that I keep next to my bed out of its holster. We are wondering what the animal might do next when Irene sees that it is back – and again it charges at her window with that same low growl. I swing my revolver towards the window and fire without hesitation in the direction of the sound. The animal crashes hard against the tent, dislodging a tent pole and peg and tilting the tent inwards onto us. Complete silence follows the noise of the shot. The animal has disappeared without a sound. Both attacks have taken place with undoubted intent from a distance of less than five metres.

We grab important gear and get out of the tent. Irene gets into the Cruiser while I climb onto the roof rack with my revolver and torch. I shine the torch around the koppie to see where the animal has gone, still under the impression that it is a spotted hyaena. I hear it move on loose rocks behind the koppie and a moment later its ears and eyes appear above a boulder at the koppie's edge. It seems unhurt and intent on us once more. While it is still peeping over the boulder, I aim the revolver into the rocks to its right and fire another shot to scare it off. This time I can hear it move away across the loose rocks behind the koppie. I decide to drive around the koppie and westward along the track to see if it really has moved away.

We drive for perhaps 300 metres but find nothing. We drive back to our camp and to our amazement find the tent flattened to the ground – with a lion on top of it, chewing and clawing at the canvas. When we come near, it gets up and moves a few metres away to the side of the koppie and crouches down. We drive past to a spot where we can turn easily and then turn back towards the koppie, and are now able to take photos in the vehicle headlights. We are still shaken by the attack and the added shock that it isn't a hyaena but a male lion. We immediately notice that it is collared. In the headlights, it appears young and gaunt but healthy. It sits watching us for a few minutes, then gets up and walks back down to the tent, hunkers down and starts chewing on its kill'.

Lion attacks on people are rare, particularly when considering the number of tourists visiting Africa's game parks and wildlands each year, often camping in places without predator-proof perimeter fences. While some attacks on people in tents have been recorded, these are extremely isolated. Ours is a highly unusual situation. The tenacious determination of a thin but still healthy looking and very capable male lion is particularly perplexing.

I decide to try to save our tent from further damage and drive towards the lion along the track at speed, continuously hooting the vehicle's horn. The lion immediately jumps up and runs off perhaps thirty or so metres and then turns back to face us. It crouches down but remains within reach of our torch and thus in sight. Irene keeps her eyes and the torch beam on it, while I hastily pack up our camping gear, with the tent roughly rolled up with bedding still inside. After some manoeuvring, I manage to tie the heavy tent roll onto the roof rack. We then drive away and up to the nearest main road, where we find a level spot to spend the rest of the night in the vehicle and recover from the shock of the attack.

On a brief reconnaissance of our camp at sunset, we had found no spoor of wildlife. We'd noticed only the single spoor of a lone gemsbok along the access track. We'd had sundowners on top of the little koppie, but had decided to turn in without making a fire, satisfied with a few snacks after the long day. We'd spent about half an hour taking photos of the moon and clouds using a tripod, and had gone into the tent at around 9:30. Irene had been woken up by the lion tripping over one of the tent ropes. Then everything had happened very quickly. Amazingly, we had not received a scratch. Irene was closest to the attacks, but had escaped completely unhurt. The scenario might have ended very differently, had I not had the revolver along. A single round of bird-shot from a .38 Special had averted an ugly outcome. The lion, too, had appeared unhurt.

In the morning I immediately inform Colgar Sikopo, Deputy Executive Director, Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) of the incident via WhatsApp. We then examine the damage to our tent – the roof is in shreds, the window where the lion had initially attacked is badly torn and our blankets and pillows have been partly ripped open. We feel great relief that we had no longer been in the tent during the final attack.

When repacking the gear, we realise that we are missing a few tent pegs and the box of firewood we'd brought along. We thus drive back to our original camp. On the way we find that the lion had first walked towards our camp on our in-bound tracks of late afternoon; it is possible that it had been attracted by and followed our vehicle. Later information would corroborate this assumption. This lion may have been habituated to vehicles as a source of food.

Now the lion is nowhere to be seen. At the tent site we find that it had soon come back and walked around on top of the marks I had made while dragging the tent to the vehicle. We collect our things and head out to the main road, and along it to the coast and Swakopmund. While I drive, Irene looks through the photos on her camera and sees that the lion had in fact been grazed by my shot, though this is hopefully a superficial wound; bird-shot is unlikely to cause serious harm to the body of a grown lion. When we come into an area with mobile phone reception, I phone Colgar to relate the incident in full. He is extremely supportive and undertakes to immediately inform regional MEFT staff of the danger the lion poses for people in the area. Through my brother Heiko, I also inform Russell Vinjevold, human–wildlife conflict expert for Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC), and Dr. Phillip Stander, the well-known lion researcher who has spent most of his life studying these lions.

Potentially dangerous or even deadly confrontations with wild animals are generally rare. Yet they are a prospect of all true wilderness experiences and thus should not be overemphasised or dramatised. After our lion encounter, I reminded my wife of the time we had very narrowly escaped a collision with a city bus that had run a red light at high speed, a collision that would in all likelihood have been fatal for us and our daughter. At the time, deeply shaken, I had followed the bus to its next stop, gotten the driver's name and reported the incident. Yet our modern society is numb to such everyday dangers. Telling the story does not get much of a reaction. The lion story has been very different.

Namibia's desert-adapted lions are famous. Any incident involving them generates immediate social media excitement and often makes local newspaper headlines. In recent weeks, newspapers have reported on starving desert lions, some of which have had to be put down, and others relocated for rehabilitation. The situation of these lions is extremely complex. They live in an arid, marginal environment, but one that is also utilised by local people and their livestock. The lions are a key attraction for tour operators and self-drive tourists, but also the focus of a number of NGOs working on community conservation and development issues. Many of the community conservancies across which the lions roam also manage conservation-hunting concessions. All of this creates a very volatile meld of often conflicting interests and aspirations.

During the first decade and a half of the new millennium, the lion population of Namibia's northwest experienced generally favourable conditions and expanded significantly in both numbers and range, from a low of around two dozen in the mid-1990s to about 180 in 2015 – the highest number in nearly half a century. Yet prolonged drought, characterised by below average and often extremely erratic rainfall has in recent years eroded the lions' prey base, as wild ungulate populations have crashed. The ongoing drought has also decimated livestock numbers. Dry times generally concentrate wildlife around available water points, for a time giving predators a bounty of food. As ungulate populations crash, the advantage shifts. And when some rain then falls, as it has in recent months, the remaining wildlife rapidly disperses far and wide. Lions are left with few, widely dispersed prey animals and may quickly face starvation. In desperation, they start hunting any prey they can find, which is often domestic animals. The lion population has now been reduced significantly, probably to well under 100 individuals.

This scenario is not new to Erongo–Kunene. The late Garth Owen-Smith, who spent his life doing community-based conservation work in what he called the Arid Eden, witnessed a comparable scenario of starving lions and increased human–wildlife conflict in the northwest in the early 1980s. At the height of the lions' population boom in 2015, Garth predicted the situation the lions now face, when he related his experiences of the 1980s to me. Philip Stander, who knows these lions better than anyone, agrees that we are experiencing a recurring cycle, one that is a typical part of arid systems. But Philip points out that we now have much more knowledge of how these lions survive in the desert – and in years of very low rainfall – and can thus hopefully manage the situation differently.

In recent years, a variety of systems and technologies have been implemented to reduce conflicts with lions. A large percentage of the adult population is collared, enabling close monitoring of lion movements. An early warning system alerts communities to the presence of the predators in their area. The Lion Rangers, co-founded by Philip and Russell, actively work with communities to avert conflicts as they arise. Combined with predator-proof stock enclosures and other mitigating measures, this is making a major difference. Losses have been significantly reduced. Yet they can never be eliminated entirely as long as livestock and large predators coexist. Understandably, local community members at times feel that mitigation is not enough. Numerous lions have been shot or poisoned. Human-induced mortalities are the main cause of death for adult lions in Erongo–Kunene. The turbulent history of the lions in this area has been well-documented in various publications. More than any other predator, lions instil deep fear in people.

Tourism is a new complication that was not part of the equation in the 1980s, when leisure travel was nearly non-existent here. I've regularly visited and worked in the northwest for the past three decades, and have climbed the Brandberg half a dozen times, first in 1993 and most recently in 2008. In the early years, the few routes in its vicinity were single tracks. Now vehicle tracks fan out on either side of many original tracks in broad, badly corrugated bands, sometimes several dozen metres wide. Remnants of fireplaces litter the riverbeds. Many camel-thorn trees are badly damaged by people collecting firewood. Off-road driving is a major issue. The area feels overrun, and visitor behaviour is often far from ideal. The lions are one of the main attractions. There are clear indications that, in attempts to ensure sightings and photo opportunities, the Ugab lions have been fed by tourism operators and/or individual tourists. The unusual behaviour of the lion that attacked us may have been triggered by behavioural imprinting that associates vehicles with food.

When we arrive in Swakopmund, we find out that on 22 April, other people had been attacked, presumably by the same lion, at the Ugab River less than 40 kilometres from our Brandberg camp. The incident had been posted on Facebook and forwarded to us via WhatsApp. A tour guide and his 72-year-old father had been busy doing minor repairs to a tourism route in late afternoon when they had been accosted by the lion. It had lunged at the older man's legs and scratched him badly. The guide had managed to chase off the lion by hurling rocks at it before it could inflict more damage. Although the lion had only retreated a short distance, the men had been able to get back to their vehicle, pack it and drive through the night to Windhoek. The injured man required 20 stitches for his wound.

It is not tourists who are most at risk here. Tourists offer often ill-prepared but generally very fleeting targets. At official accommodation sites, they are relatively well-protected by staff and safety in numbers

. The local communities who live here day in, day out face the real dangers and diverse challenges posed by the lions. Having free-roaming lions in an area where resident communities rear livestock is always problematic. Things become much more complex when a considerable number of tourists want to see desert-adapted wildlife, and particularly desert-adapted lions. The wildlife becomes habituated to the tourism presence and loses its natural wariness of vehicles, and to some extent people.

The often-made claim that communities are keeping their livestock in areas where they shouldn't be, or never have, is patently wrong. Firstly, this is the communities' land; they have the right to decide where to herd their livestock. In some cases, agreements with tourism operators and zoned core wildlife areas should create livestock-free zones, but the land remains communal farmland and in times of drought such zoning may need to be adjusted. Secondly, archaeologist John Kinahan's research has clearly shown that livestock herding in the Central Namib, including the Brandberg area, has a history of well over a thousand years. The desert-adapted pastoral livelihoods only collapsed in the centuries after the arrival of the first Europeans, when unequal trade with the livestock herders disrupted their established systems. Humans have been a part of this environment for many millennia. To talk of a pristine desert environment now being abused by people is an inappropriate simplification.

It must be emphasised again and again that Erongo–Kunene is not a national park or game reserve. These are community conservation areas that seek to achieve a balance between farming and conservation, a very positive aspiration emerging from a turbulent past. Namibia's communal areas are the remnants of pre-independence apartheid policies. Some of the most marginal areas in what was then South West Africa were allocated as tribal homelands

for designated ethnic groups. Many people were forcibly relocated here from areas expropriated for use as white farmland. At the time, there was no public interest in these arid reaches of the country. While lions were actively exterminated from white-owned farmland as vermin, the homelands were left to their own devices and development was sorely neglected. The huge inequality that still exists between communal and freehold farmland is a legacy of white minority rule.

Today in independent Namibia, the greatest inequality in Erongo–Kunene lies between rich tourists seeking sightings of desert lions and elephants, and resident communities who must tolerate dangerous wildlife while receiving few benefits from it. Attempts by members of the Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organisations (NACSO) and a few conscientious tourism operators to introduce traversing fees, channel tourism traffic onto preferred routes, or otherwise improve the benefit–impact ratio of tourism have had only limited success. While agricultural land uses are becoming more and more untenable in a region increasingly affected by climate change, the decision to shift to wildlife and tourism-based livelihoods must come from the local communities themselves – and must generate worthwhile benefits for them.

During the week, Russell Vinjevold informs me that by 28 April, our

lion, identified by Philip Stander as the five-year-old male Xpl-115, had made its way east along the Ugab River. At the Brandberg White Lady Lodge, it had managed to enter a mule stable, a solidly built structure with high brick walls. The lion had killed one of the mules, while another five mules stood terrified at the back of the stable. Phillip was at the site before sunrise the following morning. With the help of MEFT personnel from nearby Uis and the lion rangers of the Tsiseb Conservancy, Philip managed to keep the lion in place and the situation under control. The MEFT, aware of the dangers posed by this lion, had already arranged that it could be transferred to a rehabilitation centre as soon as it could be located and immobilised. This was done on the same afternoon by a team from the N/a'an ku sê Wildlife Sanctuary.

On Friday 30 April, a week after the attack on our tent, I'm on the phone with Rudie van Vuuren, co-founder of N/a'an ku sê. Xpl-115 had been flown to the sanctuary near Windhoek the day before and was doing okay. Rudie tells me that N/a'an ku sê's first priority is to save the life of a conflict predator, usually by moving it out of the conflict area. Once this has been achieved, the animal's future can be assessed. Xpl-115 will be cared for at the sanctuary and, if this is deemed appropriate by the MEFT, it may be released back into the wild once it is healthy. N/a'an ku sê has achieved positive results with the rehabilitation and relocation of cheetahs and leopards. Lions are more difficult, but the MEFT, Phillip Stander and N/a'an ku sê all see the temporary removal, rehabilitation and subsequent return of currently starving desert-dwelling lions as a possible option to preserve their uniquely acquired knowledge of the desert environment and thereby help to safeguard the desert-adapted population. Importantly, lions can't be kept away from the desert for too long, or they will loose some of their learned desert survival skills. The return of Xpl-115 to the northwest could also be complicated by its recent, seemingly imprinted behaviour towards people.

Dr Maaike de Schepper, the vet who immobilised Xpl-115 and accompanied its transfer, informs me that the lion did not sustain serious injuries from the shot I fired at it, and that the wounds should heal quickly after she thoroughly treated it. The lion is being rehabilitated away from any contact with people and is only monitored by remote cameras so as not to create any further associations between humans and food. Where its future may lead remains to be seen.

By now, news of the lion attacks is making the rounds on social media and in the newspapers. Irene and I are frequently contacted by people wanting safety advice before travelling to Brandberg. Considering the number of people who camp in the northwest, two cases of attacks on people by a desperately hungry and negatively habituated lion should not be blown out of proportion, dramatic as they were for those involved. They should, however, serve as another warning that the overall conservation situation in Erongo–Kunene is dire. The drought has been a major factor, but human influences have exacerbated the crisis.

The effects of the drought on the environment have undoubtedly been worsened by widespread and prolonged overgrazing, as well as by some over-harvesting of wildlife by some conservancies prior to the drought. Conversely, there can be no doubt that the growth of the lion population has significantly increased the hardships of the local people. Such human–lion conflicts are something that few freehold farmers in Namibia have to deal with. While communal farmers have received a variety of assistance to reduce conflicts, these are mitigating measures, not benefits. Few actual benefits from the presence of lions – or tourists – flow to individual households. Some exemplary tourism operators are ensuring benefit streams, but self-drive tourists generally contribute little or nothing other than paying for occasional accommodation.

There are solutions to the diverse challenges facing the desert lions and broader conservation and livelihood issues in Erongo–Kunene. Many are already being worked on. The current situation can serve as further impetus for action, and the MEFT has announced that a revised lion management plan is being developed. Broader initiatives need to better manage tourism impacts while significantly increasing revenue streams for local communities, thus giving them the means to shift away from unsustainable agricultural practices and to safeguard wildlife populations.

The list of potentially dangerous animals in African wildlands is long. Some danger is always a part of being out there. I'm fortunate that my work in the conservation sphere takes me to most corners of Namibia, and often to places not accessible to the general public. In the course of 30 years of regular explorations of Namibia on foot, I have been charged by elephants, pestered by spotted hyaenas, and had close encounters with leopards, hippos, buffaloes, crocodiles and venomous snakes. All were dramatic and frightening in their own way. Most were in daylight or twilight. The fundamental fear of determined, repeated attacks in the dead of night by one of the great predators of Africa is something different. It is primordial; it stirs our deepest fears. And yet, the lion attack was not more dangerous than the bus that ran the red light. And it is a lot less likely to ever happen again. It was no more than a minor drama in a complex conservation landscape.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

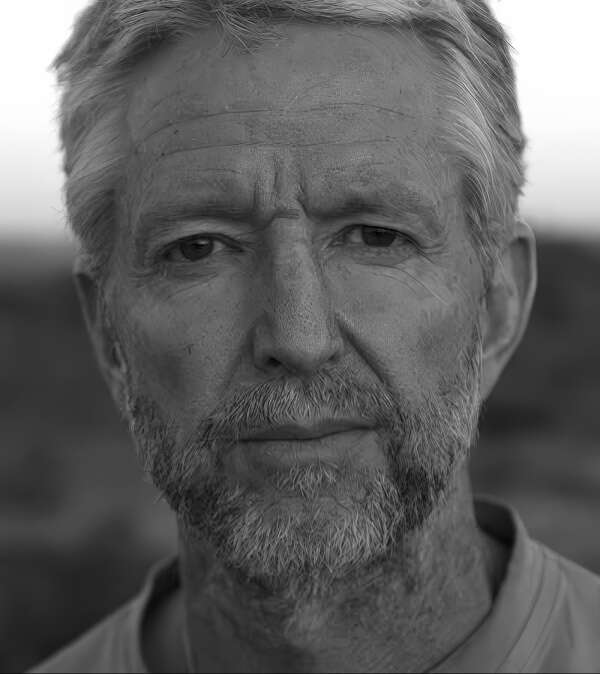

Helge Denker is a Namibian writer, artist and naturalist. He has worked in various sectors within the Namibian tourism and environmental spheres for the past three decades. He compiles information on conservation and the environment for diverse applications and publishes regular articles on environmental issues.

Helge Denker is a Namibian writer, artist and naturalist. He has worked in various sectors within the Namibian tourism and environmental spheres for the past three decades. He compiles information on conservation and the environment for diverse applications and publishes regular articles on environmental issues.

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.