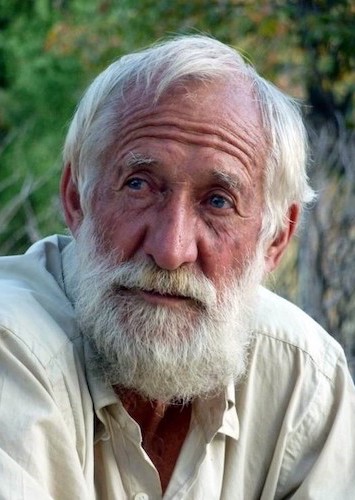

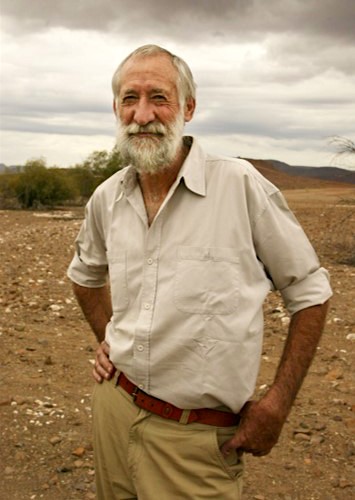

Tribute to Garth

By Brian Jones and Chris Weaver

8th August 2020

Garth Owen-Smith, well-known Namibian conservationist and pioneer of community-based conservation, passed away peacefully in the presence of his long-time partner, Dr Margaret (Margie) Jacobsohn, on 11 April at the age of 76 years. He had suffered two extended bouts with cancer. Garth is survived by Margie, his sons Tuareg and Kyle, and his grandson Garth, who unfortunately could not be with him in Namibia due to current travel restrictions.

Garth’s contribution to conservation in Namibia is immense, and went beyond the preservation of wildlife. He has been instrumental in changing the way we think about conservation, emphasising the role of local communities and traditional leaders in managing our wildlife sustainably. Garth’s early work with local communities in the Kaokoveld in the mid-1980s demonstrated that involving local farmers in conserving wildlife was the key to maintaining wildlife on Namibia’s communal land.

Leading conservationists acknowledge that the community game guard system introduced by Garth and local headmen led to a decline in widespread commercial poaching of rhino and elephant. This approach laid the foundation for the conservancies that have since been established in communal areas across Namibia.

In the late 1980s, Garth and Margie founded the non-governmental organisation Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC), which today is Namibia’s leading community conservation NGO. Working in the Kunene and Zambezi regions, IRDNC now supports close to 50 of Namibia’s 86 registered communal conservancies. Some of the conservancies in north-western Namibia currently host the last free-roaming populations of black rhino in the world. Garth’s conservation contributions have been internationally recognised. Among the numerous distinguished awards bestowed upon Garth and Margie are the 1993 Goldman Grassroots Environmental Prize for Africa, the 1994 United Nations Global Environmental 500 Award, the 1997 Netherlands Knights of the Order of the Golden Ark Award, and the 2015 Prince William Lifetime Conservation Award from the Tusk Foundation.

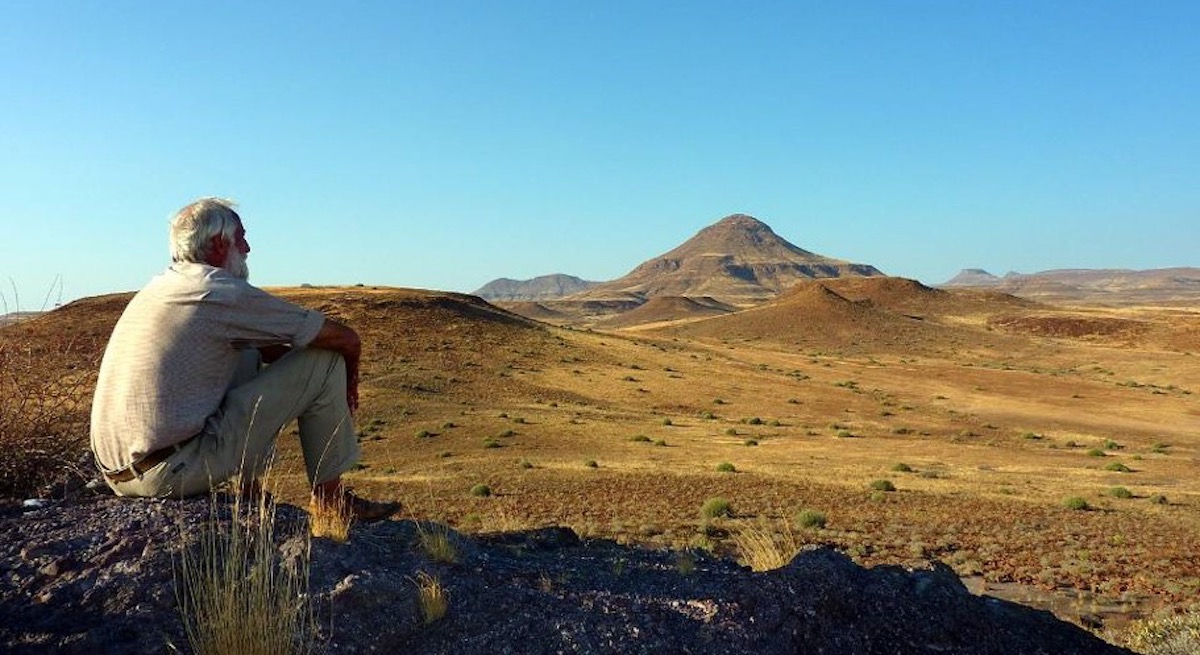

Garth was an incredibly principled person who made great personal sacrifices for his lifelong drive to place communities at the forefront of conservation. As he noted in his autobiography, An Arid Eden, his sons Kyle and Tuareg “paid the price for their father’s obsession” with conservation in the Kaokoveld. His pioneering vision and legacy will continue to guide community conservation in Namibia and the world. It was an honour for us to work with Garth and to consider him a friend.

Garth’s approach to working with local communities was based on listening to what they had to say, and understanding their perspectives on conservation. Brian Jones remembers working with Garth Owen-Smith and Margie in the then Caprivi Game Reserve, now Bwabwata National Park, just after Namibia gained independence in 1990:

“I was a young conservation official and we were conducting a survey to see what was happening after the withdrawal of the South African Defence Force (SADF). In one village the Khwe San residents told us we must take away all the animals and birds – they didn’t want them there. I thought that we had better move on to the next village where we might have more success, but Garth stayed seated, pulled out his pipe, tamped it down and tried to light it a few times – buying time to think about this problem. After gentle probing from Garth the villagers acknowledged they had always lived with wild animals and that they had been part of their way of living. They wanted to keep wildlife but were against the way the SADF had been imposing conservation on them, such as shooting donkeys and horses and firing over the heads of women collecting veld food near an army base. After that we had a great discussion about how we could work together to conserve wildlife. This was to be a recurring theme in all my work with local communities in Namibia – they want wildlife for its intrinsic value for cultural and spiritual reasons, but had been ignored or branded as the enemy in the way conservation was being implemented by the ‘white outsiders’ in those days”.

Chris Weaver was new to Namibia in 1993 when he travelled to the eastern floodplains of Caprivi (now the Zambezi Region) with Garth to assess the area’s remnant wildlife. He recalls, “We spent evenings camping with the community game guards in what was once a wildlife hotspot, yet we saw very little wildlife during our trip. Shortly afterwards, Garth and I were summoned to the Bukalo Khuta (council) to meet with the Honourable Chief Moraliswani of the Basubia tribe, who shared his vision of wildlife returning to the sacred Salambala Forest. Once the royal hunting grounds of the Basubia people, the wildlife in this area had been decimated during Namibia’s freedom struggle and the Chief was concerned that the youth among his people would grow up not seeing or valuing wildlife. In the early 1980s the Chief had asked the Nature Conservation officials to create a national park around Salambala, but the request was turned down. Shortly after independence the Chief applied to the new Directorate of Forestry to proclaim Salambala as a State Forest, but the request was similarly declined.

“Chief Moraliswani had thus called us to explain the conservancy concept and how the Basubia people might go about establishing a conservancy. After we explained the process, the Honourable Chief assigned one of his senior Khuta members to appoint a provisional conservancy committee. Two weeks later we received a list of nominated committee members. The local community game guards warned us that the senior Khuta member had appointed a weak and self-serving committee.

“Garth then set up another meeting with Chief Moraliswani to discuss how we might strengthen the committee. However, before we could even air our concerns, Chief Moraliswani informed us that he found the nominated committee to be unacceptable and that he would personally appoint the committee. Ten days later we received the new list, which was greeted with enthusiasm by the game guards. Little did we know that the Chief had summoned the area’s most notorious poachers to the Khuta and informed them they were now the guardians of Salambala’s wildlife and responsible for the creation of the Salambala Conservancy. This decision turned out to be a stroke of genius. In 1999, one year after registration of the Salambala Conservancy, zebras were seen migrating from Botswana to Namibia for the first time since the 1970s. Today, more than 6,000 zebra spend six months a year on the Salambala floodplains as part of what is now recognised as the longest terrestrial mammal migration in Africa. Chief Moraliswani’s vision of returning wildlife to Salambala was a critical part of this amazing success story.”

Our recollections of Garth’s work illustrate his approach to conservation, which proved successful in two extremely different parts of Namibia, both environmentally and culturally. Garth firmly believed that the people who lived with the wildlife would be its best custodians, which was a truly revolutionary idea at the time. A measure of the extent to which Garth was honoured and respected in the Kaokoveld is the insistence by local people that he should be buried there with a traditional ceremony which took place at Wereldsend on 6 May 2020. The Namibian conservation community suffered a great loss, but we are determined to keep Garth’s legacy alive by working together to keep our communal conservancies strong and effective, in the wake of the current global economic crisis and into the future.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options: