Climate Change in Namibia Part 3: National Actions

3rd November 2021

World leaders descended on Glasgow in Scotland on the 31st of October for the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) to discuss their collective efforts to mitigate and adapt to a changing climate. President Hage Geingob is attending COP26 and Namibia submitted its own Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) that sets out its goals for tackling climate change during the next five years.

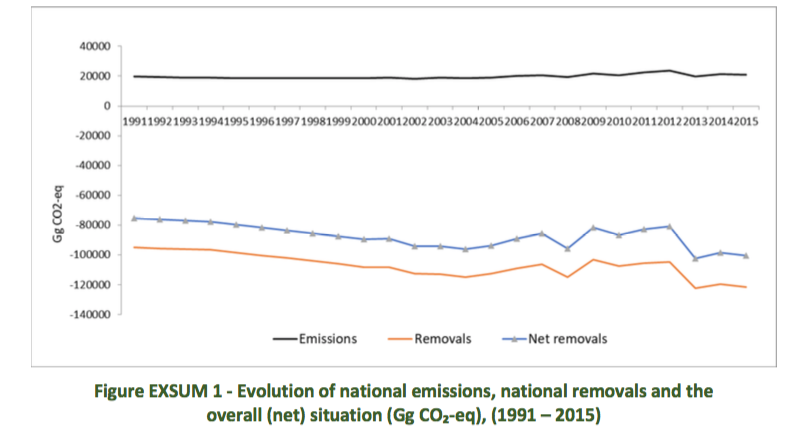

As we have seen in Part 2 of this series, Namibia is among the world's most vulnerable countries to climate change, yet it is not a major greenhouse gas emitter. Most of Namibia has retained its natural vegetation and it has relatively few carbon-emitting industries and a sparse human population, thus creating a net carbon sink. About two-thirds of the energy required for Namibian electricity needs is imported from South Africa (produced from nuclear and coal power plants), while local energy production relies mainly on hydroelectricity and a growing solar energy sector.

Namibia's struggling economy was dealt a further blow by the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent collapse of international tourism arrivals. The new catch phrase around the world is “build back better” – i.e. re-creating the world's economy to become more sustainable and resilient to shocks. How can Namibia use this new global agenda to address its own need to adapt to climate change while simultaneously implementing other reforms to meet economic targets?

The current NDC proposes cutting Namibia's emissions by 91% below a business as usual baseline by the year 2030 (‘business as usual' means the expected emissions in 2030 if nothing were done to reduce emissions between now and then). The Agriculture and Forestry sector is the main source of Namibia's emissions (accounting for 80% of emissions in 2015), but it is also the main carbon sink, which means that it absorbing more carbon than it emits. The Namibian NDC states that 90% of the funding required to meet this ambitious emissions reduction target will have to come from external sources (read this article for more on whether or not this is realistic).

The main commitment to reducing emissions entails reducing the rate of deforestation by at least 75% (it would be better to eliminate deforestation entirely by balancing the level of harvesting with that of recruitment and growth), which will also ensure that woodland areas remain carbon sinks. Bush thinning, with bush biomass as a product, is not considered deforestation as its function is to rehabilitate degraded rangeland and improve ecosystem function. Addressing the issue of clear-cutting slow-growing hardwoods in the north-eastern parts of Namibia should therefore be a national priority, thus showing genuine commitment to addressing climate change.

Timber harvesting in the north-east must therefore be strictly controlled and managed for the benefit of rural Namibian communities. Commercial harvesting of hardwood timber should only be allowed after a thorough, transparent and verifiable resource assessment is completed to ensure sustainable harvest. Any harvested timber ought to be processed in Namibia to add value to the product (e.g. through furniture production), and no raw timber in the form of logs or planks should be exported. Woodlands in the north-east should be primarily managed for subsistence use by the people living there – particularly members of Community Forests. State Forests must be formally proclaimed and protected, while other key woodland habitats (e.g. wildlife corridors) must be identified and protected. An objective, transparent monitoring system for woodland cover is required to show the relative success of these efforts.

Reducing emissions in the energy sector requires moving away from reliance on fossil fuels (mainly coal) and towards renewable sources of energy. President Hage Geingob recently promoted Namibia as a future hub of renewable energy production, particularly focusing on producing green hydrogen. Hydrogen gas is produced from water using electrical power that can come from conventional energy sources (coal power plants) or renewable energy sources (e.g. solar, wind); using the latter option makes it green

hydrogen. The gas is stored in compressed or liquefied form and can be used as a fuel by certain types of electric vehicles. Unlike normal petrol or diesel engines that produce carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide as by-products of combustion, hydrogen-fuelled engines produce water vapour. Green hydrogen is therefore produced and used in environmentally friendly ways.

The current exploration for oil in the Kavango Regions (containing some of Namibia's key woodland ecosystems) sends mixed messages about Namibia's political commitment to this issue. Rather than reducing fossil fuel reliance as promised in the NDC, it shows that the government is still entertaining the idea of expanding fossil fuel use. Furthermore, development of this nature in the Kavango Regions is likely to increase opportunities for deforestation, thus casting doubt on Namibia's commitments to reduce deforestation.

Nonetheless, since Namibia is already on the right side of the carbon credit sheet, the more urgent need is to adapt to climate change. A nationwide assessment of Namibia's vulnerability to climate change revealed that the Kavango (east and west), Omusati and Zambezi Regions are the most vulnerable. The arid southern parts of the country (Karas and Hardap) were actually rated least vulnerable using this index system, because farmers in these areas already pursue desert-adapted livelihoods (smallstock or wildlife farming). Households in the north that currently rely on seasonal crops may no longer be able to harvest enough to eat under projected reduced rainfall conditions, thus jeopardising their food security.

Conservancies, Community Forests and Farmers Clubs, particularly in the vulnerable north-east, are the key to developing locally applicable agricultural and forestry practices that will increase climate resilience in these areas. Interventions include introducing conservation agriculture, improving forest management, planting trees and increasing market access for non-timber forest products (e.g. thatching grass, honey, devil's claw). While several projects of this nature in the north-east are managed by non-governmental organisations and funded by external donors, these interventions should become an integral part of government policies and be scaled up with government financing. Community Forests should receive technical and financial support comparable to that provided to communal conservancies.

In its negotiations at COP26, the Namibian government can take several steps to ensure that the country benefits from international commitments and pledges. Perhaps the most straightforward of these is to revoke the oil drilling exploration license in the Kavango with immediate effect, thus sending a strong message that Namibia's future energy production options will be climate friendly. Second, business conditions for green energy projects should be made as attractive as possible for international investors.

Third, an effective, participatory, nation-wide reforestation programme must be established with both national and international financing (e.g. through the Green Climate Fund and bilateral donors). Tree planting efforts must first identify suitable species and formerly wooded habitats where these can be planted, and incentivise the people living in these areas to protect these young trees. In urban environments, planting fruit and shade trees in locations where they will be cared for (e.g. near schools) will improve the living conditions and food security of the urban poor. Local entrepreneurs should be assisted to establish nurseries to provide saplings for these planting projects.

Finally, the results of climate adaptation and reforestation projects should be collated to attract international climate financing. To do so, Namibia needs to have a clear action plan and means to record national progress in both mitigation (e.g. woodland cover) and adaptation (e.g. livelihoods) strategies. The strategy outlined above is about more than just checking boxes and climate change window dressing. If the proposed actions were implemented, they would make a substantial positive contribution to the lives of Namibian people and thus prepare them for the challenges associated with climate change.

This post is part three in a series of four articles dealing with climate change in Namibia. Please click on the links below to view the others.

1: Defining the Terms 2: Current and Projected Changes 4: Local ActionsFor articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.orgThe Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.org

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.