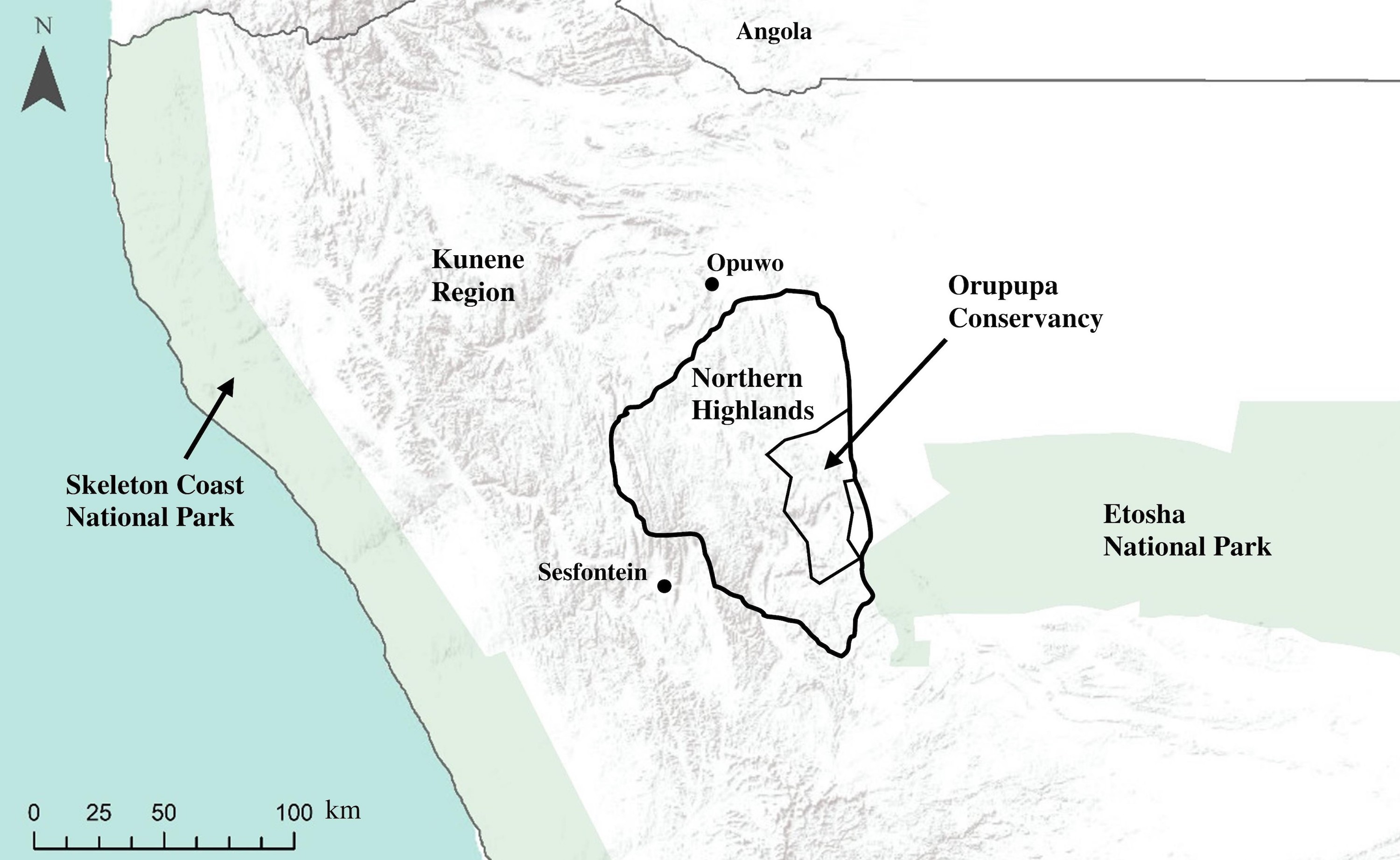

The northern part of Namibia's Kunene Region, formerly known as the Kaokoveld, is renowned for its beautiful landscapes, fascinating indigenous cultures and desert-adapted wildlife. One of the Kaokoveld’s most well-known wildlife species is the elephant, which in this area is uniquely adapted to survive in the desert. Yet in the mountains of the Kaokoveld lives another remarkable sub-population of Namibia’s elephants that few people know about; referred to locally as the highland elephants

.

What makes the highland elephants special? In a recent journal article on these elephants, Michael Wenborn and collaborators noted that these elephants appear to have adapted to live in mountainous, rocky environments. While most African savannah elephants tend not to spend energy walking up steep slopes, and therefore exclude mountainous areas from their range, these elephants readily walk up and down steep mountain slopes. The elephants spend parts of the day in the mountains, where they tend to browse on tree species associated with the mountain slopes, moving down to waterholes at night to quench their thirst.

Local community game guards can distinguish the footprints of some elephants that spend time in the rocky mountains from other elephants because the highland elephants’ feet appear smoother with fewer cracks than those of other elephants. The game guards speculate that the highland elephants get smoother feet by walking through rocky areas in their mountainous habitat.

The Kunene mountains don’t just host elephants, however. There are many villages in the conservancies in this area, located on the western boundary of Etosha National Park. The people in this area, mostly Herero, have coexisted with elephants for years. Unfortunately, the recent prolonged drought in 2018-19 greatly reduced the resources available to humans, livestock and wildlife. Climate change will potentially increase the risks of more frequent and severe droughts in future, which would further increase the competition for resources.

How drought worsens human-elephant conflict

Both humans and elephants are threatened by prolonged droughts, particularly as competition for water becomes increasingly intense. Rainfall in the Kaokoveld can be as low as 50-70 mm/year and some places go for a whole year with no rain. Adult elephants consume between 100-200 litres of water per day, and they can become destructive if they do not find water where they expect it, like at pumped water points. Repairing pumps or water tanks is expensive and difficult in remote areas, so communities have little choice but to ensure that elephants have water to drink, even if pumping extra water requires spending more money on diesel.

The people in northwest Namibia have also had to adapt to drought, especially since most of their cattle died in 2018-19 due to the lack of grazing. More community members started growing vegetable gardens near their houses than they did in previous years, while those who already had gardens expanded them. These vegetable gardens became a new source of conflict, however, as elephants started wandering into the villages in search of this new food source. The elephants usually avoid human settlements as risky areas, but the vegetables are highly nutritious and easy to eat, making these gardens irresistible.

The drought has led to desperate times for wildlife and local communities, which could result in desperate measures that put both people and elephants in danger. Elephants coming closer to villages could result in human deaths during surprise encounters, which might lead to calls for the government to intervene and destroy problem-causing elephants. More support is needed to alleviate the never-ending resource struggle between rural people and elephants.

The role of conservancies in managing human-elephant relations

Namibia uses a community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) approach to wildlife conservation outside national parks, which allows local communities to make decisions on how to manage their natural resources by establishing communal conservancies. Since the first conservancies were established in northwest Namibia during the 1990s until now, elephant populations have grown. Elephants have expanded the range of areas where they occur in response to reduced poaching pressure, which is a result of the conservancy programme.

Although some conservancies are able to create jobs and distribute community benefits due to income generated from elephants and other wildlife, this has not been the case for Orupupa Conservancy. Orupupa has received no tourism investment and therefore generates very little revenue, while its members have not benefited from local employment or other benefits since its establishment in 2011.

Michael Wenborn and colleagues co-authored the article referred to above with the Orupupa game guards, acknowledging their contribution of data and knowledge. While the conservancy cannot afford its own mitigation efforts at this time, the dedicated game guards and their valuable data provide an important starting point that they can use to address this growing problem.

A first step towards a solution came in 2022 when Orupupa signed a 20-year service-level agreement with Conserve Global (operating through its local entity, Kunene Conservation) to address key challenges across the landscape and deliver benefits to both people and wildlife. An important early win has been to secure support from the Elephant Crisis Fund (ECF) to implement vital measures to safeguard critical waterholes, with several positive outcomes that bode well for the future.

Finding ways back to coexistence between highland elephants and the people of Orupupa

Other than the game guard records, there is no regular monitoring of elephants in the highlands to track their movements and estimate their population. Knowing more about elephant movements is key to developing solutions and strategies that work for this conservancy.

The game guards are best placed to undertake such research, provided they are sufficiently trained and equipped to collect this extra information. In some cases, they have already identified individual elephants that have caused frequent problems by raiding gardens and damaging infrastructure. In their research paper, the scientists and game guards suggested establishing an early warning system among villages of the presence of potentially dangerous elephant herds.

The game guards currently lack adequate resources and equipment to carry out their basic duties, let alone to expand their work to include elephant monitoring. Besides better equipment and training, game guards in Orupupa and many other conservancies need better pay and an appropriate means of transport to get to every part of their conservancies where conflict is reported.

We know from other communal areas and private farmlands in Namibia that walls and electric fences can deter elephants from vegetable gardens and water infrastructure. The Namibian government with funds from the Game Products Trust Fund, the Environmental Investment Fund and assistance from non-governmental organisations continues to upgrade waterholes across the Kunene Region. These are protected with walls and use solar rather than diesel pumps, thus reducing elephant damage and the cost to supply elephants with water. However, the scale of the problem means that it will be many years before all waterholes meet this elephant-proof standard.

Other options that have received less attention in the Kunene Region include digging trenches big enough that elephants will not cross and creating chilli fences. Households can make their own chilli fence by soaking old cloths in chilli oil and then hanging the cloths on the fences around their vegetable gardens. Elephants usually touch fence lines with their sensitive trunks before breaking them, so the chilli oil can be a powerful deterrent, especially if used in combination with other deterrents.

The future of elephants and people in Orupupa is looking more promising than ever before, given their new partnership with Conserve Global. Unfortunately, many other conservancies host important wildlife species, but do not attract sufficient external investment to offset the cost of living with wildlife. Prolonged and more frequent droughts are expected due to climate change, thus increasing human-wildlife conflict as competition for resources intensifies. Long-term partnerships, new sources of income and innovative conflict mitigation ideas are needed in conservancies throughout Namibia to counter the growing threat of climate change.

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.