A lioness prowling along the desolate Namibian coastline spots a seal packed with enough nutrients and energy to sustain her for the next few days. Hungry and desperate, she creeps nearer, crouching in some reeds to hide her presence. Just before she launches her final attack, she spots a fisherman standing with his back to her, oblivious to the danger.

Contrary to popular belief, healthy lions have no desire to fight with humans. The lioness retreats to a safe distance, still hidden by the reeds, and waits until nightfall when the fisherman goes back to camp and she can continue hunting. Lions and fishermen sharing the same coastline can be dangerous, however, for both sides.

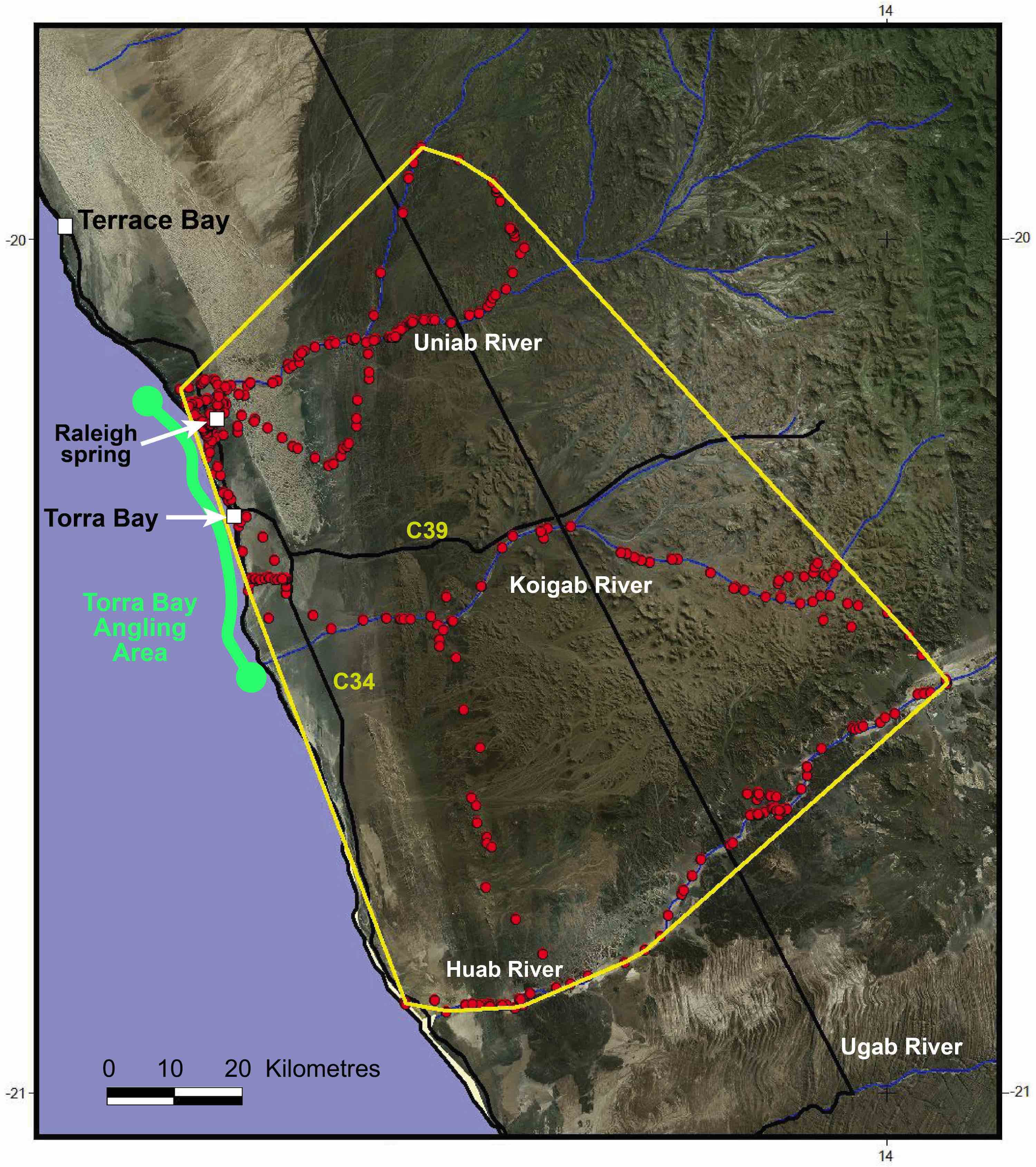

In this case, the lioness had a satellite collar fitted to track her movements and help prevent dangerous encounters. She spent at least half of the fishing season period (1 December 2022 to 31 January 2023) around the Torra Bay Campsite, yet without coming into conflict with the fishermen. This success story is largely due to the efforts of Dr Philip Stander and his research team working alongside the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT).

What are lions doing at the Skeleton Coast?

Let's back up a little to find out how and why desert-adapted lions ended up on the coast. The Skeleton Coast National Park was established in 1971 to safeguard the unique habitat and its endemic animals found in this harsh environment. Soon afterwards, authorities found evidence of lions living near the coast and hunting seals and other animals living there. In 1985, an adult male lion was spotted eating a pilot whale that had washed up on the shore. These were the earliest accounts of lions inhabiting coastal areas and eating marine species.

This unique lion population was in grave danger during the 1980s due to conflict with livestock farmers in the inland parts of their huge home ranges. Drought and rampant poaching of lion prey animals brought desperate farmers and hungry lions into close contact, resulting in a lion population crash. By 1990, all known lions of the Skeleton Coast National Park had been killed. They were absent from the park for the next ten years.

When the Skeleton Coast lions of the 1980s were killed, their knowledge of the marine food resources along the coast was lost. The few remaining desert-adapted lions had to survive using more normal lion prey found inland, like zebra and giraffe. The population started to recover around the same time that the first communal conservancies were established in the mid-1990s, which focused on conserving antelope that were previously poached. After finding a few remaining lions in this desert region, Dr Stander launched the Desert Lion Conservation research project (DLCP) in 1997 to study them.

During the following 15 years, the lions that Dr Stander tracked would re-visit the coastline from time to time but none of them used it as a permanent hunting and feeding ground like their ancestors of 1980s. Due to more prey animals being available inland in the conservancies, the lion population increased steadily and reached a high of 180 in 2015 during the early years of a long drought when prey animals were weak and easy for lions to catch.

As the drought dragged on for several more years and prey animals declined, the situation of the 1980s threatened to repeat itself, with desperate farmers and hungry lions again fighting over scarce resources. The Lion Rangers Programme was initiated in this time to help keep lions away from livestock and thus prevent history from being repeated.

It was during this time that some lions rediscovered the rich food resources at the coast. Two lionesses from different prides independently began hunting marine species such as Cape fur seals and cormorants. This new source of food was a lifesaver for these lions and their cubs that regularly returned to the coast to feast.

The lioness and the fishermen

The lioness at the beginning of our story, designated by the researcher's code Xpl-108, is part of a litter of three female cubs born in 2013. Their mother was one of the lionesses who rediscovered the coastal resources, and she passed this knowledge on to her cubs. After their mother's death, the young lionesses started hunting around the Uniab Delta, just north of the Torra Bay Campsite that is popular with fishermen. In mid-2019 Xpl-108 was fitted with a satellite radio collar to monitor her movements and help prevent her from coming into conflict with people.

The lioness's movements recorded during fishing season revealed that she adapted to the presence of anglers and tourists visiting the coast to avoid encounters with humans as much as possible. During the day, she moved inland to rest in dense reed beds or narrow gorges. At night, she hunted and searched for prey along the beach. Moving inland reduced her food intake and increased her energy expenditure. As a result, she frequently returned to the seaside to hunt.

Dr Stander and his team didn't rely on the lioness keeping herself safe from humans, however. The team posted regular updates on five social media platforms regarding the movement and activities of the lioness to alert the public. Further, MEFT officials were alerted of any potential conflict situations and illegal activities.

A few stubborn or curious visitors tried to get close to the lioness, while others ignored the warnings and stayed at the beach after sunset. In these cases, the researchers used a strong flashlight and hand signals to either warn the visitors to stay away from the lioness or alert them to danger when the lioness was approaching them.

The research vehicle was a constant presence whenever the lioness was close to the Torra Bay Campsite area. The researchers thus monitored human interactions with the lioness and prevented conflict before anything happened. This strategy kept the visitors' safe from the lioness and vice versa.

Can lions and fishermen continue to coexist peacefully?

The strategy of keeping the fishermen and one lioness apart in the 2022/23 season was a great success. What happens if more lions start migrating to the coast during fishing season? Will the researchers be able to prevent incidents when many lions are roaming around? We may need to adapt an existing strategy to deal with increased chances of conflict. Some of the Lion Rangers that work in conservancies could perhaps be deployed to the coast to assist during fishing season.

Outside of fishing season, the awareness campaigns on social media and at MEFT offices must continue to reach as many people as possible so that future fishermen and tourists know about the lions before they arrive.

The fact that Xpl-108 avoided people shows that the lions are unlikely to cause any trouble, but people might. MEFT officials may therefore need to fine or evict people who refuse to follow the guidelines and approach or harass lions. If visitors to the Skeleton Coast respect the authorities and the lions, there is no reason why we cannot accommodate both the fisherman and the lion.

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.