The Role of Rolling Zebras in the Desert Ecosystem

With thanks to Kenneth /Uiseb.

16th March 2022

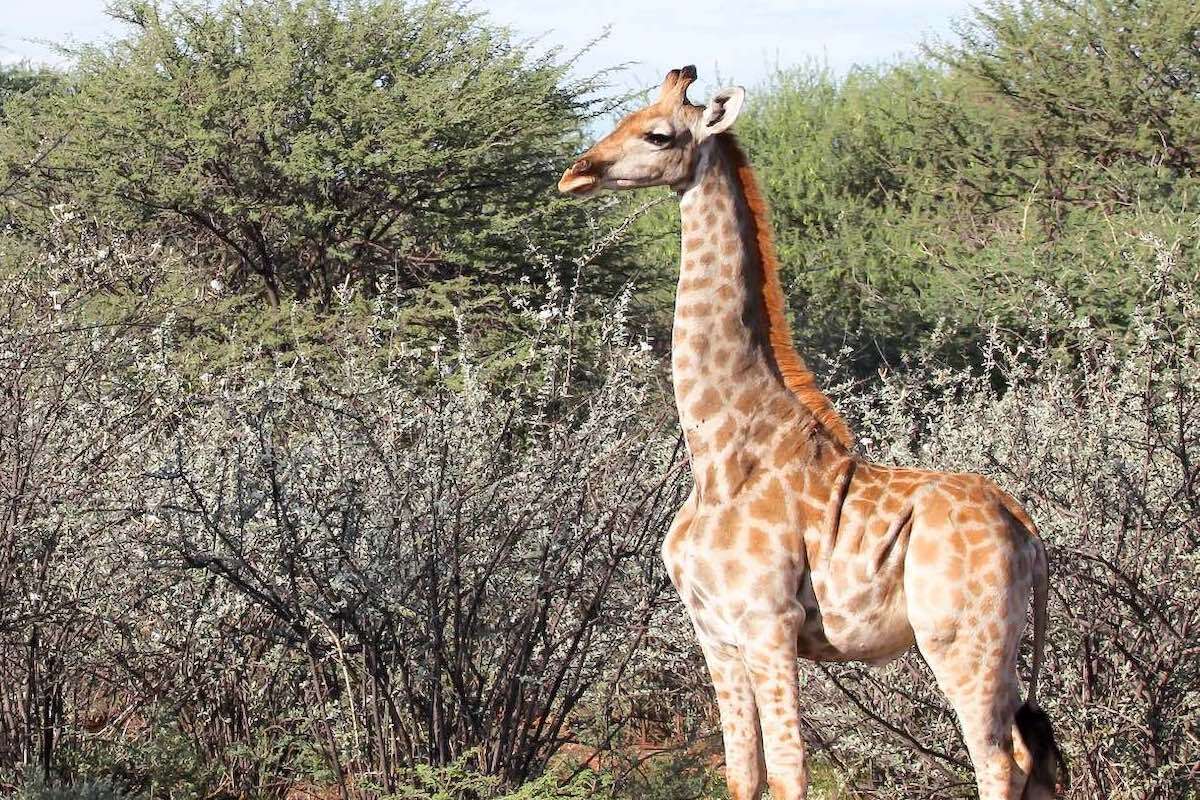

Namibia's desert ecosystems might look ageless and unchanging from a distance, but surprisingly small actions can make a real difference in an ecosystem where every drop of water counts. A recent study revealed that Hartmann's mountain zebra make subtle, yet measurable, changes to the environment just by rolling in the dust. Since none of Namibia's other desert-adapted mammals enjoy a good roll quite like zebras do, this particular role in the ecosystem as unique as their stripy coat.

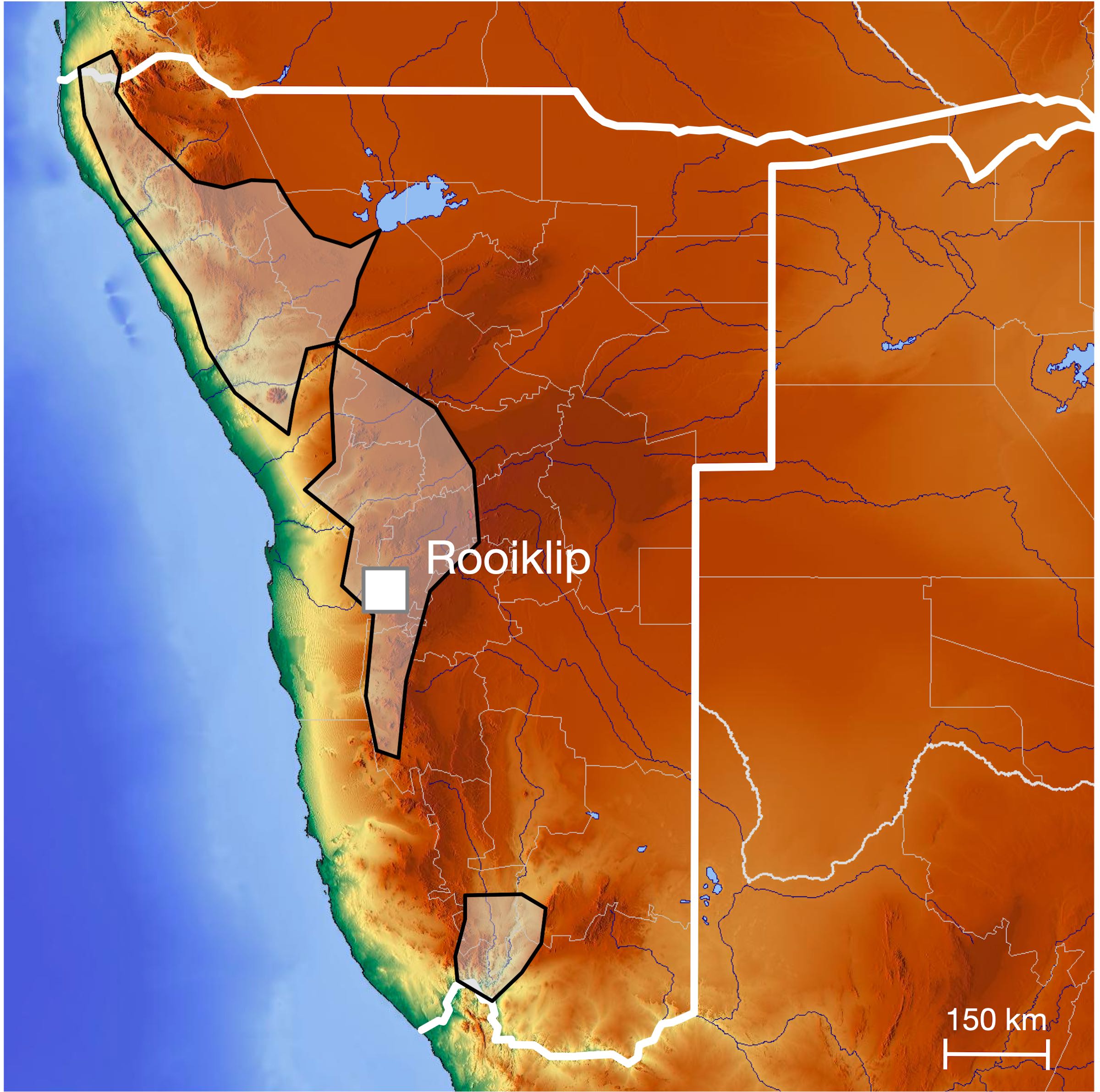

The Hartmann's mountain zebra is nearly endemic to Namibia, with small populations occurring in north-western South Africa and south-western Angola. They survive on Namibia's unforgiving escarpment by migrating or dispersing over long distances in rapid response to rainfall; retreating to smaller areas with high-quality grazing near permanent water sources in the dry season. Regardless of the season, zebras like to roll several times a day, as a form of self-grooming to reduce their load of ticks and other parasites.

A rolling zebra might not seem like a significant event, and in wetter parts of the world it may make little or no difference to the ecosystem. Yet animals as small as hairy-footed gerbils are ecosystem engineers

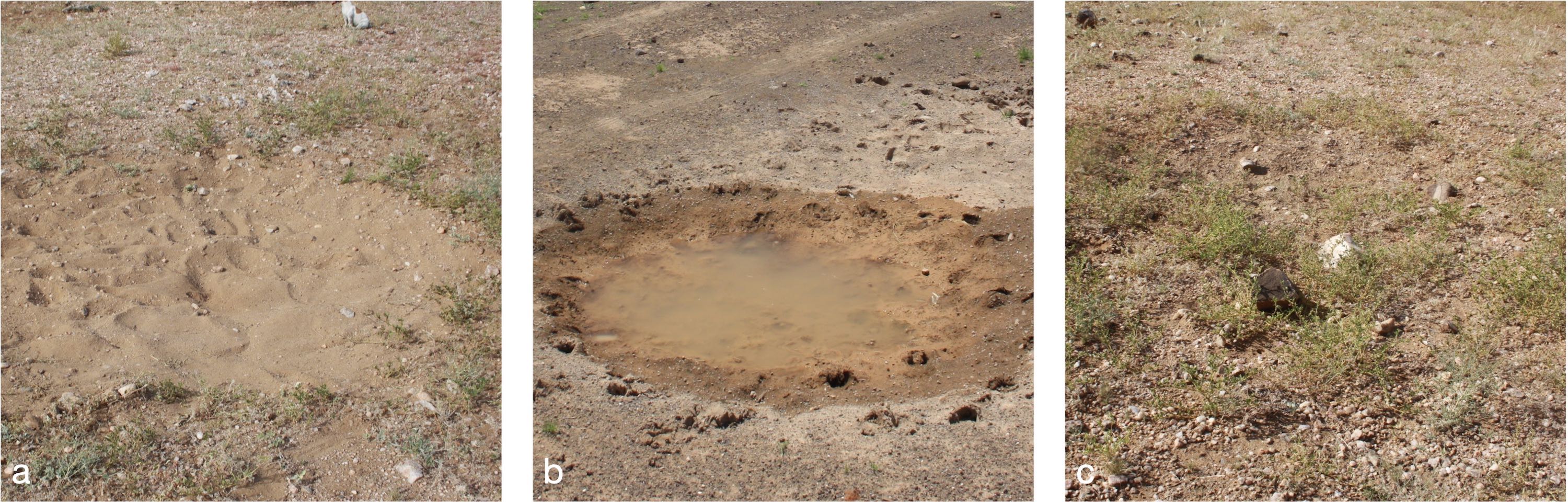

in the desert, so the idea that zebra rolling sites could have a measurable effect in this ecosystem was not crazy. Zebra use the same sites repeatedly during a particular season, but nearly 90% of the time they will abandon them and use other sites the next season. The depressions, usually about two metres in diameter and ten centimetres deep, nonetheless remain for many years after they are abandoned. Do these depressions really make an ecological difference?

To answer this question, three researchers – Thomas Wagner, Kenneth /Uiseb and Christina Fisher – mapped 656 zebra rolling sites on one square kilometre of a farm located roughly half way between Windhoek and Walvis Bay, in typical mountain zebra habitat. They then randomly selected 16 of the abandoned sites to study in detail over five consecutive rainy seasons, comparing each one with similar-sized patches of ground five metres from each site. They were especially interested in soil texture, nutrient content and moisture retention, plant composition and cover, and the activity of arthropods – i.e. grasshoppers, beetles, spiders and other invertebrates.

They found that rolling zebras make a substantial difference to the soil. The rolling action displaces larger soil particles like pebbles and gravel, leaving a deeper, finer layer of soil within the depression than outside. Any grass at the site is smothered or uprooted, leaving it bare of vegetation when in active use. The zebra also leave plenty of dung and urine in and around their favourite rolling spots.

A recently abandoned rolling site is thus a well-fertilised, grass-free depression with a thick layer of fine sand. When the rains come, water naturally pools in the depression and the finer sand retains the moisture for longer than the surrounding area. Small leafy plants that grow for just for one season (known collectively as annual forbs) take full advantage of these favourable conditions by quickly filling the bare patch with a flush of green. This vegetation is noticeably greener than the nearby reference sites (that are more grassy), which the researchers quantified using images taken from a drone flown over their study area.

The different plant composition and greater cover afforded by the annual forbs resulted in increased activity among herbivorous arthropods – e.g. some grasshopper species, cicadas and aphids. Omnivorous (e.g. beetles, cockroaches) and predatory (e.g. spiders and scorpions) arthropods responded positively to increased activity of their prey species, but the researchers could not detect increased activity of these species within the rolling sites compared to the reference sites. One possible reason is that predatory species use much larger areas than just one rolling site, although these sites probably make good hunting grounds.

Zooming out from their close inspection of individual sites, the researchers considered how the zebra's rolling habits might affect the ecosystem at a landscape level. Since the species occurs widely on Namibia's escarpment and into the pre-Namib, rolling sites must cover vast areas. From what we know thus far, annual forbs and herbivorous arthropods are likely to be the main ecological winners in this story, as these depressions create ideal micro-habitats for them.

Annual forbs mainly grow close to or in dry riverbeds, which generally have finer soils that retain moisture for longer periods. Outside the riverbeds, grass predominates on the rockier, drier soil – forbs struggle to grow under such conditions. Without zebras, the distribution of annual forbs would be more restricted, resulting in lower vegetation diversity across the landscape. Consequently, arthropod diversity and abundance may decline, with unknown knock-on effects on the rest of the ecosystem. We can therefore conclude that Hartmann's mountain zebras are more than just stripy donkeys – they are rolling ecosystem engineers.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.orgThe Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.org

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.