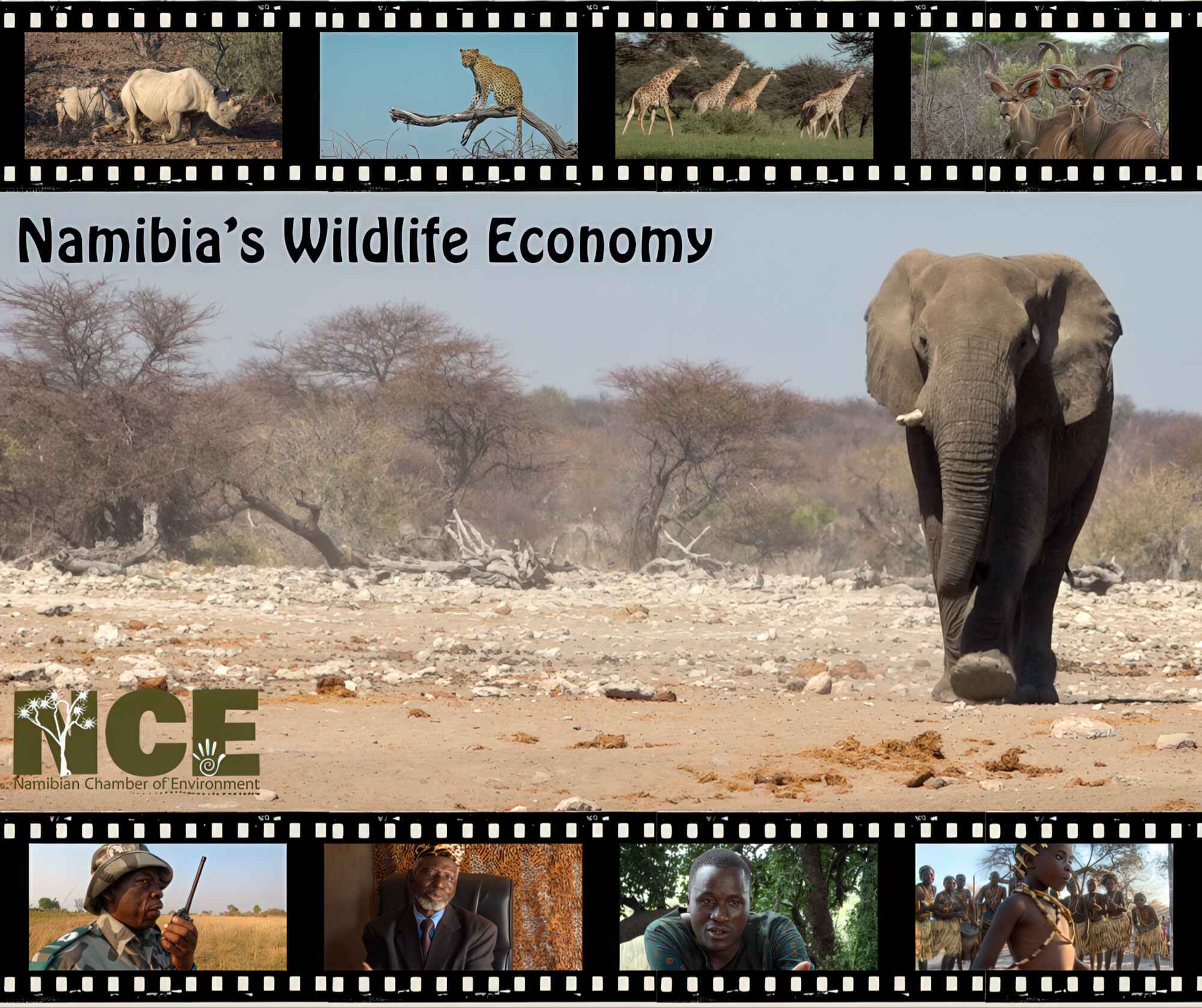

Click on the photos in this article to watch our series of films on the wildlife economy.

In a world with a growing population and shrinking space for wild animals, is there a future for Africa's wildlife beyond a few state-protected areas? Yes, there is! If we use it rather than lose it.

Using wild plants and animals in a way that generates economic returns for the people that conserve them is known as the wildlife economy. If the wildlife economy outperforms other land uses such as domestic livestock farming, then wildlife will be a more attractive option and the amount of land under wildlife will increase, as will wildlife numbers and benefits to biodiversity. Here, we focus on how the sustainable, legal use of wild animals sustains a vibrant wildlife economy and contributes to nature conservation.

This approach has resulted in Namibia's wild animal population increasing six-fold from an all-time low in the early 1970s to the highest level seen in the last 100 years. Neighbouring countries in southern Africa that have taken a similar approach to wildlife have shown similar levels of success.

The recipe for success: developing a wildlife economy

The first and most important principle is wildlife ownership or use rights for people living with the wildlife or managing the land on which it occurs. These rights enable people to generate income from wildlife on their land, which incentivises investment of time and money into nature conservation and wildlife management.

Regarding wildlife as a commodity to be traded legally and sustainably may be a difficult concept for those living in protectionist countries where the wildlife belongs to, and is solely protected by, the state. Yet this protectionist model has failed to conserve wildlife across Africa.

African countries and developing countries in most other parts of the world that have adopted this wildlife-owned-by-the-state approach have lost much of their wildlife to poaching and illegal wildlife trade. The knee-jerk response to poaching is further state protection measures and restrictions on legal international trade, without recognising that state protectionism does not work and restricting legal trade allows illegal trade to flourish. Further, it punishes those countries with successful wildlife economies by removing one of the main sources of income for sustainable wildlife management.

Once the rights to use and benefit from wildlife are in place, industries relating to wildlife must be supported and enabled rather than obstructed or over-regulated. Photographic tourism, hunting tourism, game products such as meat (venison), and live sales of wildlife are the four main ways to generate income from wildlife.

When rights holders maximise their income from wildlife using a combination of these options that is best suited to their local conditions, the value of African wildlife far outstrips cattle and other livestock—especially in semi-arid areas where livestock production is already marginal and predicted to worsen due to climate change.

Why wildlife is more valuable than cattle in Namibia

Wildlife is more resilient to climate change than domestic stock, and the wildlife economy even more so. The value of domestic stock is mainly in its meat, which is a primary production output. Wildlife produces high-quality meat and three high-value service industries, which are far more resilient to climate impacts than primary production—photographic tourism, hunting tourism and live sale of high-value wildlife species. For example, a post-breeding male kudu is worth about US$220 for its meat. As a trophy animal it is worth about US$3,800—seventeen times more.

Viewing wildlife with the same economic lens as cattle or other livestock may be repugnant to some, yet the reason why cattle dominate global mammal biomass across the globe is because cattle are valued more than wildlife. If the global market for beef disappeared overnight and no one was allowed to buy or sell cattle, there would be few cattle left on earth in just a few years. In a global climate that restricts the legal market for indigenous wildlife and depresses its value, it should come as no surprise that wildlife numbers are low and biodiversity is being lost every day.

The two tourism aspects of the wildlife economy are most lucrative for African nations when they attract international tourists that bring in foreign exchange. Since tourism is a form of international trade, maintaining a healthy tourism sector requires strong international relations and cooperation between the source and destination countries. On the destination side, countries wanting to promote tourism should make visa regulations as simple as possible and their borders welcoming towards international visitors.

Source countries have a special role in hunting tourism, since mementoes of the hunt (trophies

) are frequently exported to the tourists' home countries. While the export of trophies is not critical to the existence of domestic hunting industries, it adds tremendous value to the hunting product and supports a value chain that includes local hunting guides, hospitality services and taxidermists. International policies that undercut the value of wildlife (e.g. by imposing bans on the importation of hunting trophies) weaken the wildlife economy and limit conservation outcomes.

Conservation outweighs animal rights, but does not neglect animal welfare

Conservation outcomes—stable and increasing populations of wildlife and larger areas of intact habitat that supports biodiversity—are our key concern as conservationists. Activists that are concerned with animal rights seem to be less concerned with these outcomes than they are with the act of killing an animal as part of the wildlife economy.

While the instinct to avoid killing may seem like the surest path to protection, it ignores a simple truth: without value, wildlife becomes a liability, not an asset, to those who live alongside it. It also overlooks the fact that most antelope species increase at 25% to 35% per year, and would severely damage their environment before starving to death if their numbers were not controlled on fenced game ranches.

Animal rights advocates may equate legal hunting with poaching, since both involve animal killing. When one applies this view to other tradeable commodities, it becomes clear that the two are not the same.

Legal hunting is equivalent to the sale of goods from a supermarket, while poaching is equivalent to shop-lifting. In both cases, items are taken off the shelves and need to be replenished by the shopkeeper. Yet high levels of shoplifting will drive the store to bankruptcy and ultimately cut off the supply of goods, while high levels of shopping will lead to a more prosperous shop that can buy and sell more goods in future.

Since wildlife reproduces naturally, a wildlife manager can continue supplying wildlife to the hunting market if they manage their off-take to be lower than natural reproduction rates through hunting quotas, while controlling poaching rates. This is why anti-poaching teams are supported by hunting operators across Africa—it is in their economic interest to reduce poaching, for the same reason that shopkeepers employ security guards and install CCTV.

Although the legal, sustainable killing of wildlife is a positive thing for the wildlife economy, it need not be to the detriment of animal welfare. In many places, legal hunting reduces poaching, which can involve cruel methods of killing. Animals caught in snares or traps may suffer for hours or days before dying. Death by poison is excruciating and may lead to many other deaths of non-target species (e.g., vultures). Replacing poaching with regulated hunting is a net gain for animal welfare.

Unlike the factory farming conditions that many cattle, pigs, chickens and other livestock endure worldwide, wildlife can be hunted while maintaining high welfare standards. Wildlife lives in open, natural habitat until the abattoir comes to them in the form of a hunter under the guidance of a professional hunter. By contrast, factory farmed animals live in tiny cages and similar containment, are subjected to hormone and other chemical treatment, and are then transported often under stressful and inhumane conditions to an abattoir or place of slaughter.

Countries such as Namibia set high animal welfare standards when it comes to hunting. Captive breeding and hunting are not permitted in Namibia and the minimum size of area in which wildlife may be kept is 2,740 acres (1,000 hectares).

While trophy hunting received most of the adverse press from animal rights activists and organisations who find this a lucrative fund-raising business model, only about 1% of Namibia's wildlife population is removed in this way (with the meat going into the venison market). The majority of wildlife offtake—at least 15 times more animals—goes into the game meat sector, and this offtake is based on ecological carrying capacity to ensure sound rangeland management.

How do we further expand the wildlife economy?

Even though 80% of Namibia's wildlife is found outside national parks (the latter covering 17.6% of the country), the wildlife economy here and in neighbouring countries has yet to reach its full potential.

The game meat industry remains largely informal and undervalued. While venison is a healthier kind of meat than beef, the use of lead ammunition in game hunting undermines its health benefits. The use of unleaded ammunition coupled with better marketing of the health benefits of game meat will increase the value of this commodity and strengthen the wildlife economy.

Live sales of wildlife at game auctions are source of significant income for many wildlife ranchers, yet there remain significant barriers to further growth. The limitations on the movement and ownership of wild animals such as buffalo and wildebeest in Namibia are a case in point. Both species are highly valuable and fetch high prices in neighbouring South Africa (particularly buffalo), yet misplaced fears of disease transmission to cattle greatly limit their ownership in Namibia. Since wildlife is worth far more than cattle in Namibia, such laws should favour the wildlife industry, within reason. A more balanced approach by the beef sector would allow both sectors to better optimise their contributions to the national economy.

The wildlife economy's full potential can only be fully realised when the most valuable wildlife commodities are bought and sold on international markets. This includes rhino horn and elephant ivory, which are currently sold in large volumes on illegal markets, while legal international trade is not permitted by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

The current situation effectively prevents the ‘shopkeepers' (wildlife owners and custodians) from selling their most valuable commodity, thus making it difficult to invest in security measures against ‘shoplifters' (poachers and illegal traders). As a result, many rhino owners in both Namibia and South Africa can no longer afford to keep rhino on their land, greatly harming rhino conservation outcomes.

Using the wildlife economy to offset losses to wildlife

Although most wildlife has a tangible value in southern Africa, some species also cause high losses. The big cats, hyenas and other predators kill livestock and valuable antelope, while elephants, crocodiles, hippos and lions pose a substantial threat to human life. Elephants may damage water infrastructure and housing, and they are among the main causes of extensive crop damages.

In Namibia, the people living in communal conservancies bear the biggest burden of human-wildlife conflict, and many of them live close to or below the poverty line. Their level of tolerance for dangerous wild animals is often a result of cultural and tangible (monetary) values, with the latter coming from photographic and hunting tourism. As on the freehold farms, the relative contributions of these different types of tourism depend on the local context and decisions made by the conservancies.

The high levels of human-wildlife conflict found in Africa would not be tolerated in Europe and North America. Conserving wolves alone is a constant struggle on these continents, yet they pose minimal threat to human life and the farmers that experience the loss are not poverty stricken. These same nations have extensive hunting industries, including trophy hunting. It is therefore hypocritical to demand that Africans refrain from killing wild animals to offset their losses or generate income for their benefit.

The wildlife economy film: Promoting better understanding of the wildlife economy

Understanding the nature of the wildlife economy and its goals in relation to biodiversity conservation and sustainable development can be challenging for those who are used to the wildlife protectionist model and influenced by animal rights narratives. For this reason, the Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) created a series of films that showcase the wildlife economy in Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The interviewees share perspectives from governing authorities, conservation scientists, local communities and private landowners. Together, they explain the key pillars of the wildlife economy and principles for conservation success.

A short film (under eight minutes) distils the key messages from all of the interviewees, while a longer feature film (under 40 minutes) provides more details. Many of the links in this article refer to the full-length interviews that address the wildlife economy from different perspectives. These films are available for screening for audiences anywhere in the world (the short film includes subtitles in French, German and Spanish) to promote broader awareness of this important topic.

If you want to protect Africa's wildlife, listen to the people who live with it. Watch the films. Visit the places. Hear the voices of those on the front lines of conservation—and discover why a strong wildlife economy is the key to conserving African wildlife.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.