Why do we need plant data?

17th November 2025

17th November 2025

Knowing where plants occur, what they look like in the wild, and how they are used (and could be used) by local people is vital to plant conservation. Plants that occur only in Namibia (endemic species) and those that are mainly found in Namibia (near-endemic species) deserve special attention in national policies and development plans.

During the last two years, we entered data on Namibia’s near-endemic plants into a database we previously created for Namibia’s endemic plants. Gathering the information for our database is painstaking and sometimes difficult work, but it is worth the effort. This knowledge will enable us to better manage and conserve Namibia’s plant resources and the surrounding environment.

Each plant in our database has a distribution based on where it has been found growing in the wild. Some of our information is from collections and observations by botanical experts, while others are from plant enthusiasts. Unfortunately, we have to disregard doubtful entries (e.g., a record for a plant that is not known to occur in a particular area) if they don’t include clear photos or parts of the plant that we can use to verify the observation. All indigenous plants in Namibia are also included in this database; however, only basic information is available for these plants, and their distribution in Namibia has not yet been updated.

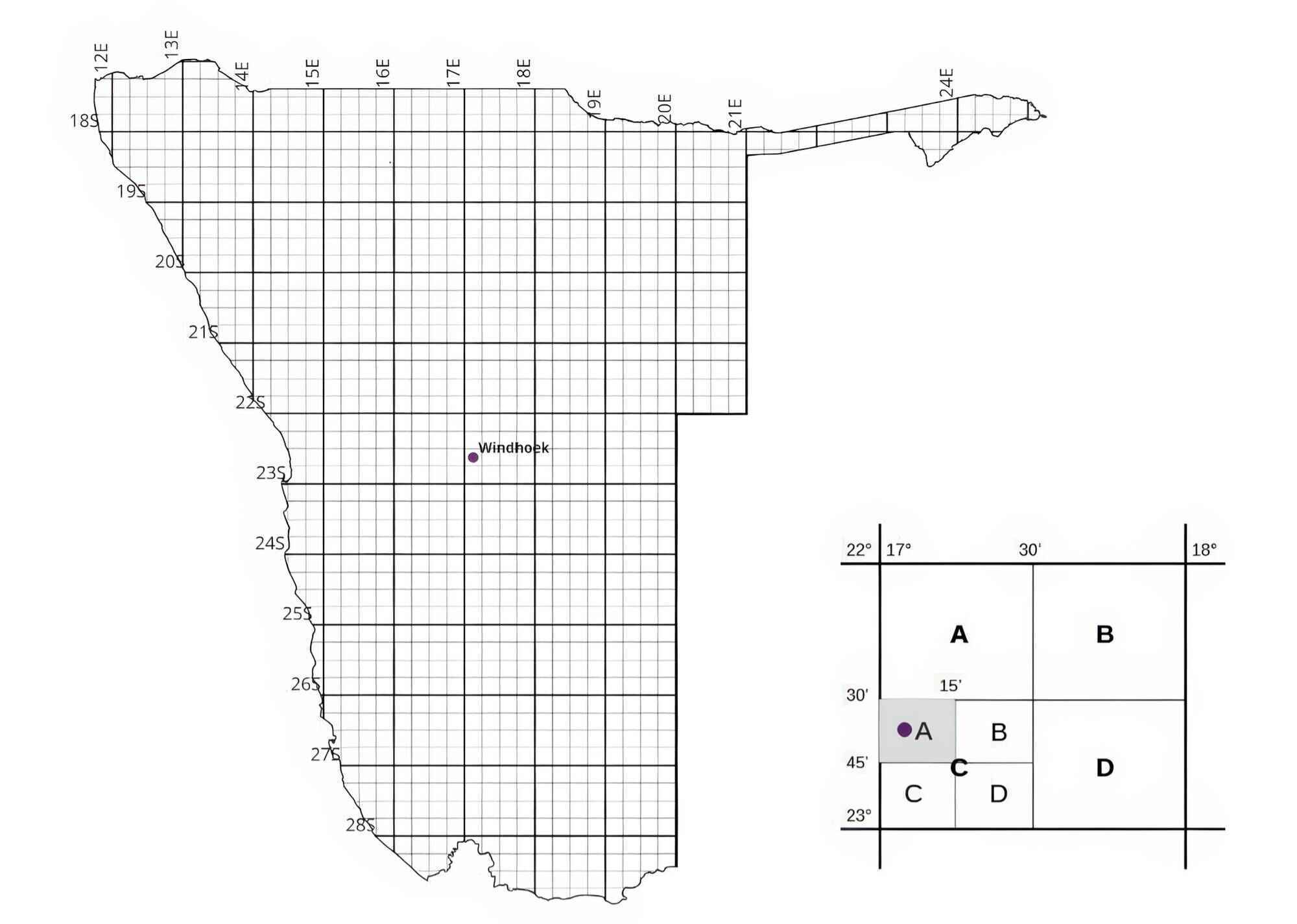

Some of the older specimens in botanical collections are associated with vague locations (e.g., between Walvis Bay and Otjitambi, or on a farm that spans thousands of hectares), which cannot be georeferenced and are therefore of no use for mapping distribution. These days, we collect accurate latitude-longitude points for each plant we sample using a GPS, but only a few decades ago, handheld GPS units were not commonly available. Instead, plant collectors used quarter-degree-squares (QDS). Our database, therefore, utilises the QDS system (see Map 1 for a quick guide), which enables us to retain the older QDS records and incorporate our newer, more accurate GPS records into these blocks for easier grouping.

Here, we provide three examples of the many ways this information may be used: 1) to identify important plant conservation areas; 2) to maximise local community benefits from plants; 3) to inform environmental impact assessments. In each example, we use real data from plants in our database and apply them to real and hypothetical cases.

Identifying priority conservation areas

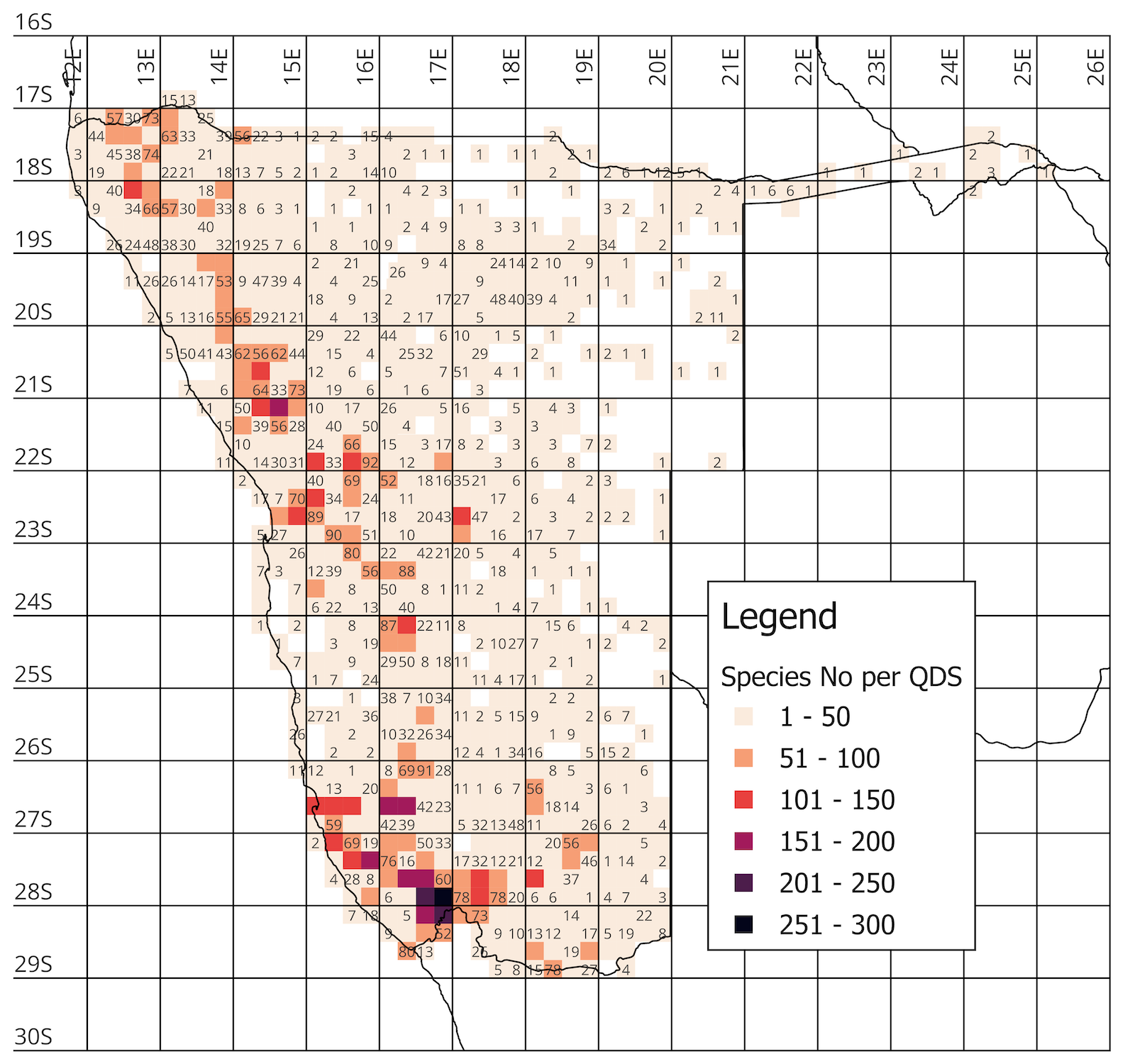

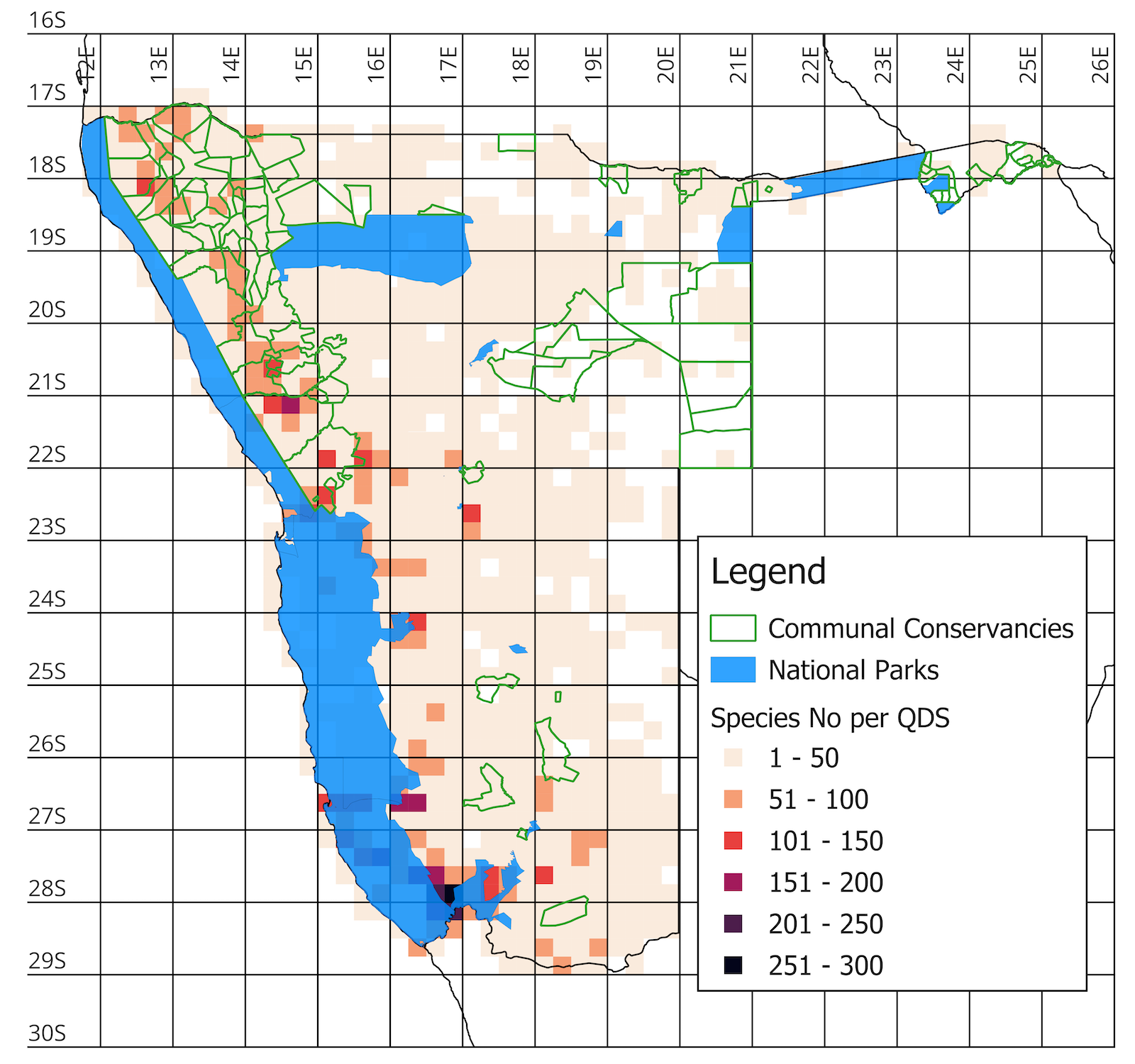

The data generated through our project provides a valuable foundation for evidence-based conservation planning. Using our database, one can map the number of endemic and near-endemic plant species that occur in each QDS in Namibia (Map 2). When you overlay this map with the boundaries of Namibia’s national parks, communal conservancies, and community forests, you can identify plant diversity hotspots and evaluate the extent to which they are currently protected (Map 3). This information can guide the relevant authorities and community stakeholders in prioritising plant biodiversity hotspots for conservation.

Our maps of endemic and near-endemic plants reveal that most of the QDS hotspots fall outside the boundaries of national parks, especially in the north-west. While six community forests have been established alongside communal conservancies in the north-west, these do not cover all the hotspots. The remaining areas are largely covered by communal conservancies, but these focus on conserving large mammals that attract tourists.

In south-western Namibia, plant biodiversity hotspots are found within the Namib-Naukluft and Tsau ||Khaeb National Parks; however, effective protection is also not guaranteed, as management efforts often overlook plants. The plants in these parks are further threatened by mineral prospecting, mining, and other proposed developments. Several of Namibia’s key areas of plant biodiversity are either unprotected or overlooked in development plans.

To address this gap, we recommend prioritising unprotected hotspots in the north-west, central-west, and south-west for future conservation efforts. National parks and community conservation areas that boast high plant diversity should include plants in their management plans and allocate sufficient resources to implement them.

Maximising the benefit of plant resources for local communities

The aim of conservancies and community forests is to effectively manage and conserve biodiversity, while simultaneously earning a living through the sustainable use of biological resources. Community forests focus on plant resources, while communal conservancies were established to conserve animals. These community conservation areas are one means of promoting the sustainable use of plant resources, and several community forests have already been established that overlap communal conservancies in north-west Namibia to serve this purpose.

Communities living in an area usually know best what plants are useful to support their livelihoods (edible plants, medicinal plants, livestock forage). In exceptional cases, such knowledge may have been lost within the community, but still exists in older plant information collected by botanists. In these instances, the knowledge should be returned to such communities. Established community forests should receive more support to develop plant-based products (e.g., oils, beauty products) that can be harvested sustainably. Plants that are special in some way, such as being photogenic or unique in the world, may, however, not be known to local communities and could be marketed for tourism purposes, thus generating income without harming the plants.

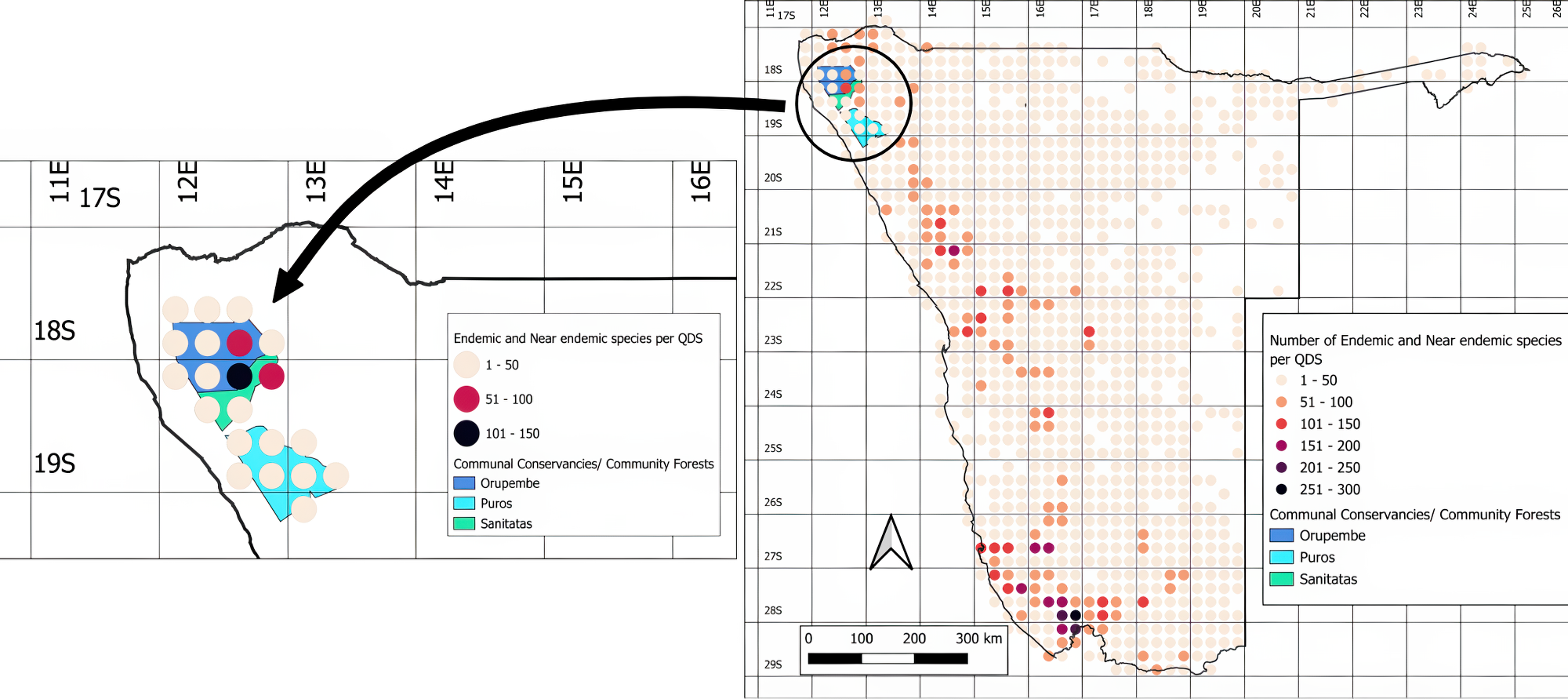

Let us consider the community forests of Orupembe, Sanitatas, and Puros in north-western Namibia (Map 4). These all share the same boundaries as the conservancies by the same names. By overlaying the number of endemic and near-endemic plants on this map, we can see that the Orupembe community forest contains an area where up to 110 endemic or near-endemic plants are found. This indicates that the eastern areas of the community forest need the most attention for plant conservation.

Tourism operations in this area could highlight the fact that nearly 8% of Namibian endemic/near-endemic plants can be observed here. One of these species is the northernmost Welwitschia population in Namibia. These Welwitschia plants are quite small, as they grow in a different environment than in the central Namib. This interesting Welwitschia locality also extends into the eastern part of the Sanitatas community forest.

The Puros community forest, although not having the high diversity of endemic or near-endemic plants as the Orupembe conservancy, houses a very special plant: Oberholzeria etendenkaensis. It is found only in this one place, in the north-east of the community forest, in the entire world. It is also the only succulent legume species in the country. Such a rare and unusual plant could be used as something to differentiate this community conservation area from others and attract more visitors. In the Puros community forest we also find the only plants of Roepera orbiculata discovered in Namibia to date. The species was previously only known from Angola.

Supporting environmental impact assessments

Environmental impact assessments (EIAs) require data on plants and animals in the area that is earmarked for development. Data on endemic and near-endemic, protected, rare, or endangered species is especially important, as their presence in the area will affect how and if the development should take place. This information is freely available through the Environmental Information Service (EIS), which hosts our plant information.

Environmental assessment practitioners, or the plant specialists who do baseline vegetation studies for each EIA, need to know what plants to expect in the area that may be developed. Baseline studies are often conducted outside the growing or flowering season to meet EIA deadlines. Consequently, many species that only appear after the rains will not be recorded during the study, while perennial plants may be difficult to identify without flowers or fruit. Knowing which plants were previously found in the area and which of those have a special status (e.g., endemic, endangered) will certainly help the practitioner produce a thorough EIA.

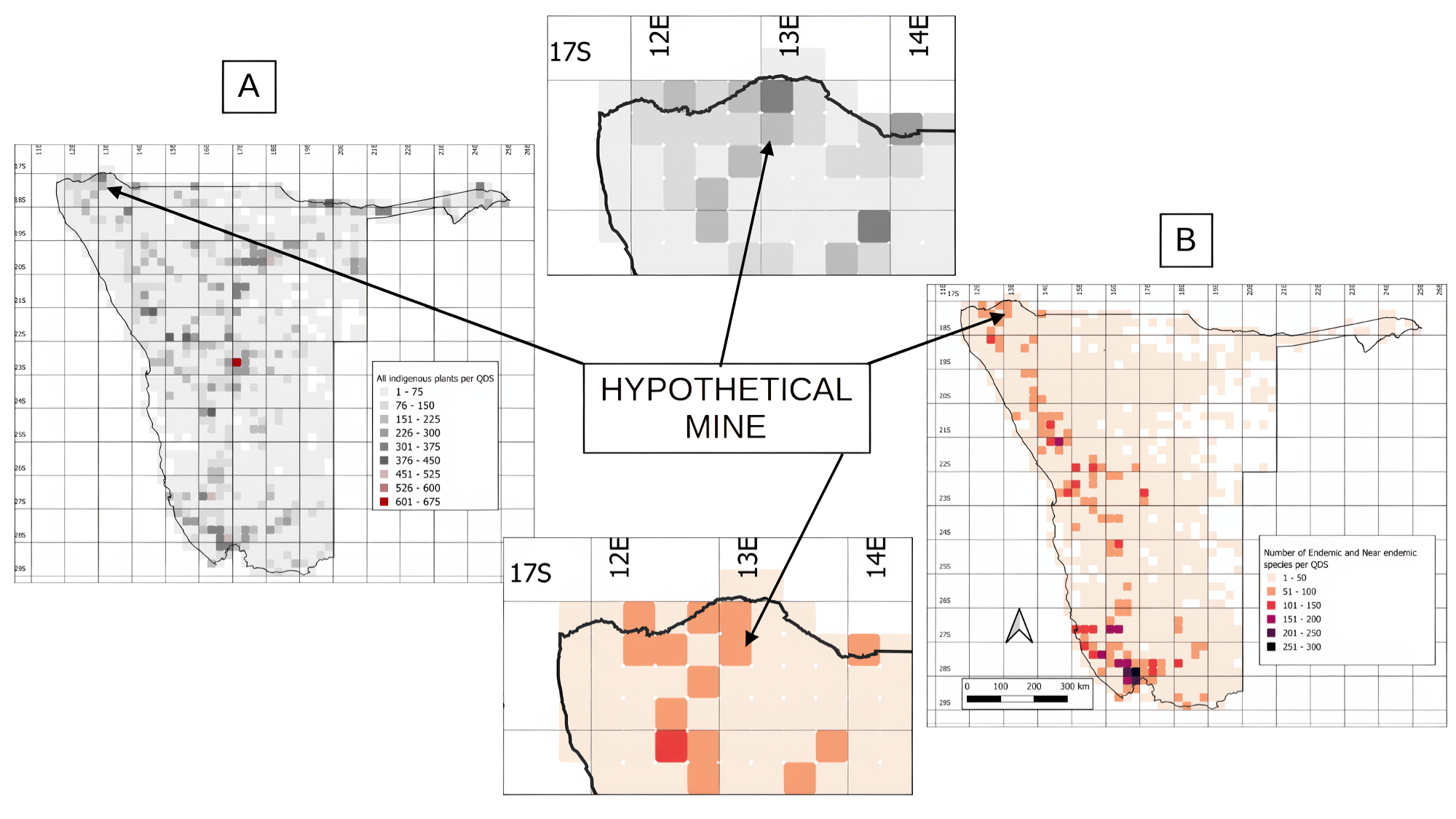

Consider a hypothetical case study: an open-cast mine north-east of Okangwati in the Kunene Region is planned within QDS 1713AC. The practitioner can access the database to determine which species have been recorded in this QDS and those in the surrounding areas. This provides a good starting point for a baseline survey, since the study area is usually much smaller than a QDS.

In this example, the study area falls within a QDS that hosts 216 plant species, 12 of which are endemic, and 51 are near-endemic. Among these plants, 27 are protected by Namibian law, and nine are considered threatened at a global level. The proposed mine is clearly in an important plant area (Map 5), and the practitioner or plant expert should take extra care to document the presence or absence of these plants during their baseline study.

The Environmental Commissioner’s office can also use the plant data to determine if: 1) the vegetation assessment was done thoroughly, and 2) the proposed development falls within a sensitive area that supports high levels of biodiversity. If the development falls into a sensitive area, a proper baseline study should be required. The Commissioner’s office can use the database to answer key questions: How many plant species were recorded by the baseline study, compared with the number we would expect in this area? Were any endemic, near-endemic, protected, or IUCN-listed species flagged? Were mitigation measures suggested, especially for the latter species? These answers will reveal whether the EIA studies were done properly.

Namibia’s plant database requires further development

The plant database is by no means perfect, complete, or 100% correct. Many more years of work will be necessary to clean up and complete our dataset, and then we will need to keep it up to date. New studies are published almost daily, many of which have implications not only for the classification and naming of Namibian plant species but also for their attributes, such as distribution range, physiology, chemistry, or genetics.

Our current collections, used for distribution mapping, are biased towards areas that are more accessible and popular, which make them seem more species-rich than less-visited areas. The square containing Windhoek (2217CA) is ranked first with 674 plant species recorded, while places like Waterberg, Rosh Pinah, Brandberg, and Epupa also have high numbers of species per QDS.

By contrast, 22% of the QDS blocks in Namibia have fewer than ten plant species recorded, while 57% have fewer than 50 species. No plant species at all is recorded in 4.5% of Namibia’s QDS blocks. Although some of these squares will naturally have low numbers of plants (e.g., in the Namib sand sea), most of the others will have more species than our records indicate. Many more baseline studies are required, which involve collecting, identifying, and maintaining plant specimens.

The current plant database is freely available and has many uses. Our work on endemic and near-endemic plants is just the start of a long-term plan to better understand, manage, and conserve Namibia’s unique flora.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.