As Namibian farmers seek to adapt to the changing climate and its impacts on agriculture, wildlife ranching offers a resilient and environmentally sustainable option that aligns with the country's conservation goals while providing economic opportunities for local communities.

Namibia, known for its vast landscapes and diverse ecosystems, has long relied on agriculture, particularly livestock farming, as a primary source of livelihood for rural communities. However, the increasing challenges posed by climate change, including prolonged droughts and erratic rainfall patterns, have significantly impacted agricultural productivity. This has left farmers and rural communities vulnerable. In response to these challenges, the inclusion of wildlife in livelihood strategies has emerged as a viable alternative for sustaining rural livelihoods in Namibia.

Studying the wildlife economy under different land uses

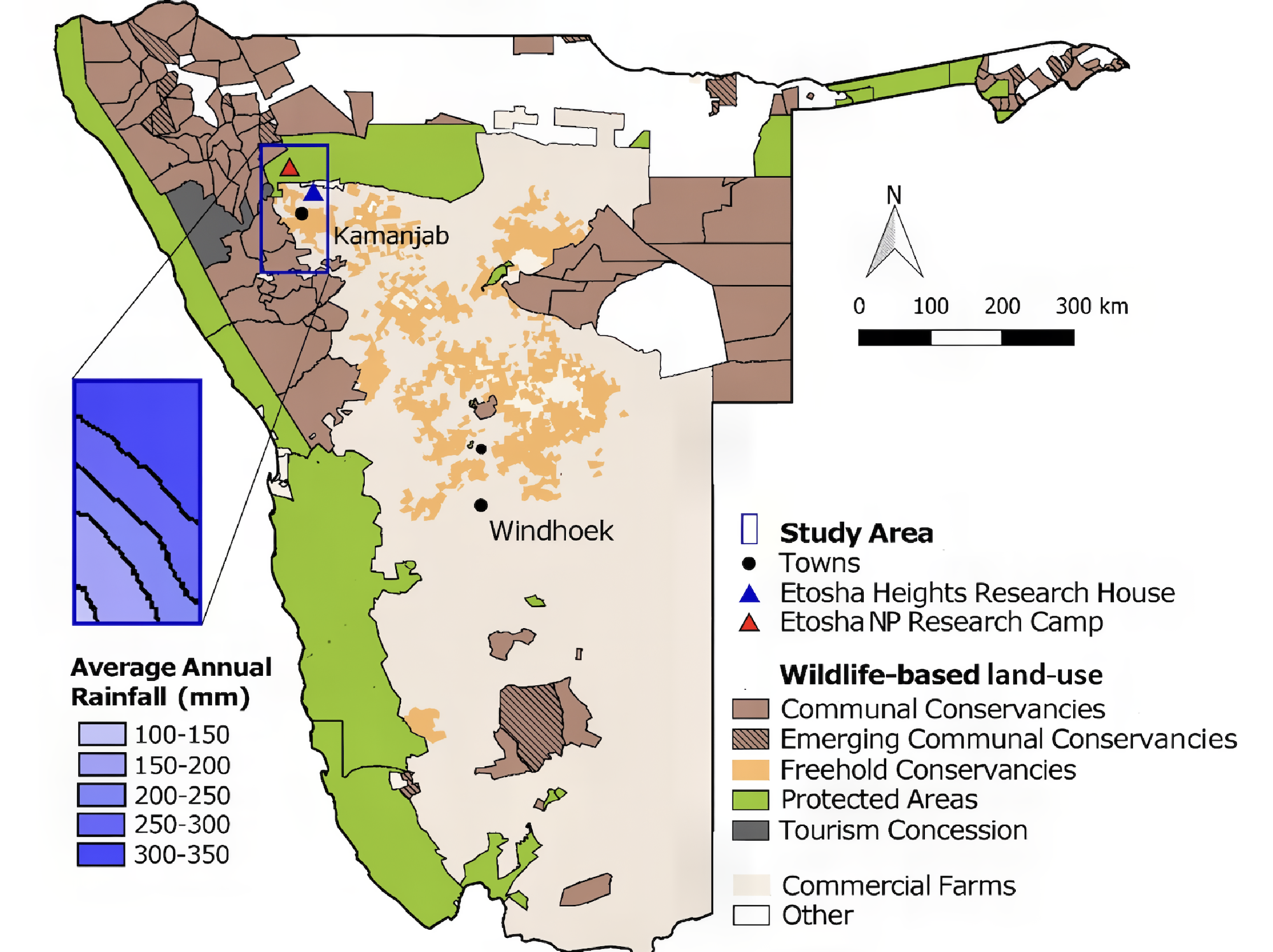

Northern Namibia, particularly around Etosha National Park, is home to several iconic wildlife species, including elephant, giraffe, zebra, springbok, gemsbok, black-faced impala, Damara dik-dik and wildebeest, many of which undertake seasonal movements in search of food and water. The areas around Etosha include communal conservancies, commercial livestock and wildlife ranches, and private reserves that rely mainly on tourism.

This mix of land use types provides ideal conditions for researchers to study how wildlife moves through different areas. Consequently, Prof. Morgan Hauptfleisch of the Namibian University of Science and Technology (NUST) and Prof. Niels Blaum of Postdam University spearheaded the ORYCS project to coordinate multiple studies in the landscape to the south and west of Etosha National Park.

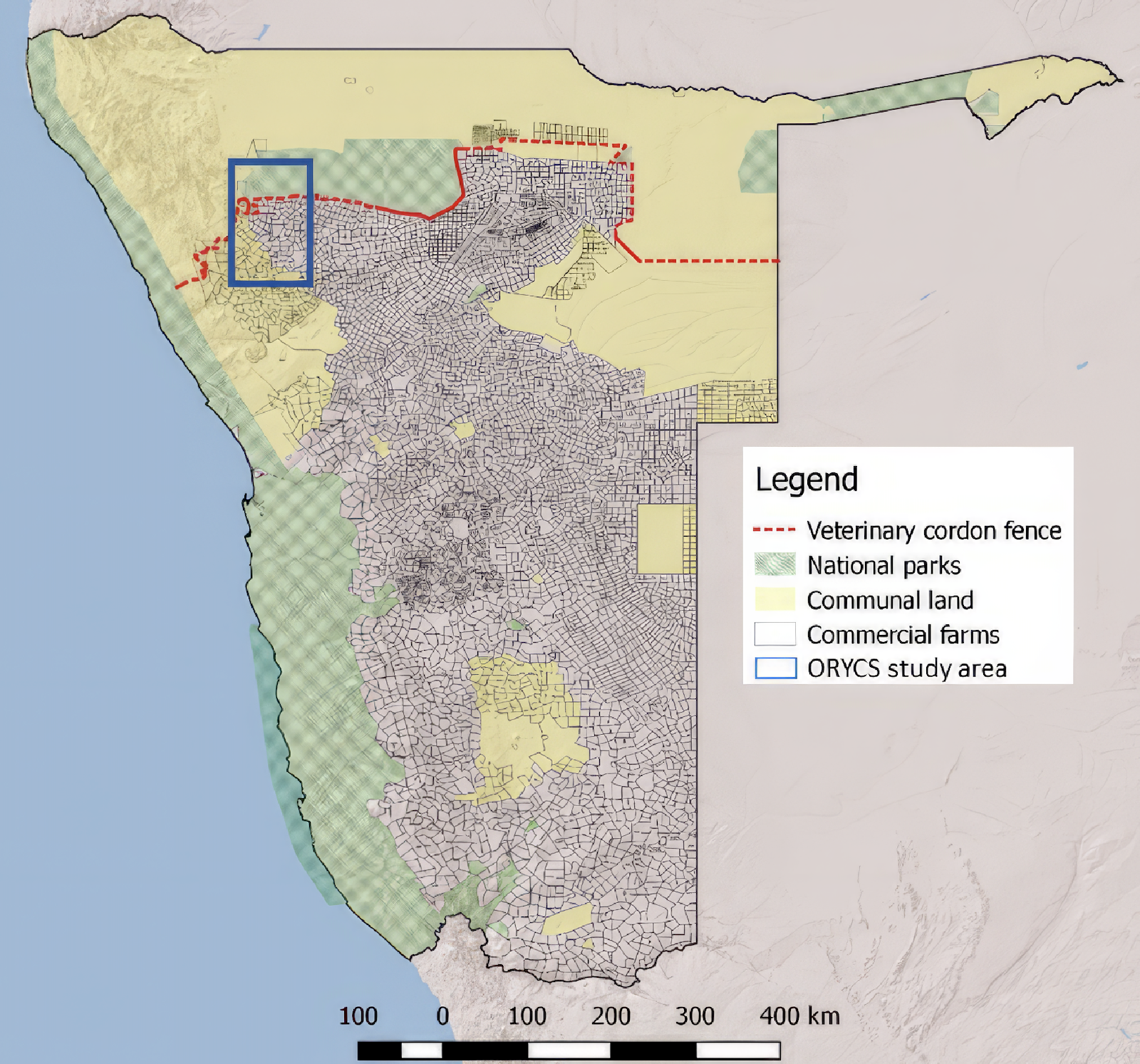

One of the key research topics for Prof. Hauptfleisch and his collaborators is fencing, which could present a challenge to wildlife survival and productivity by limiting their movement within the landscape. These fences include the national veterinary cordon fence on the Etosha boundary, high game-proof fences erected around freehold wildlife ranches and reserves and lower fences on livestock farms. Another key research topic is human-wildlife conflict, which affects different farm types and wild animal species in a number of different ways.

Wildlife ranching (also known as game farming) is the breeding, management and sustainable use of wild animal species for various purposes, including meat production, trophy hunting, live sale of surplus high value species, ecotourism, and the trade of wildlife products. In Namibia, wildlife ranching occurs on commercial freehold farms (including those on freehold conservancies) and in communal conservancies.

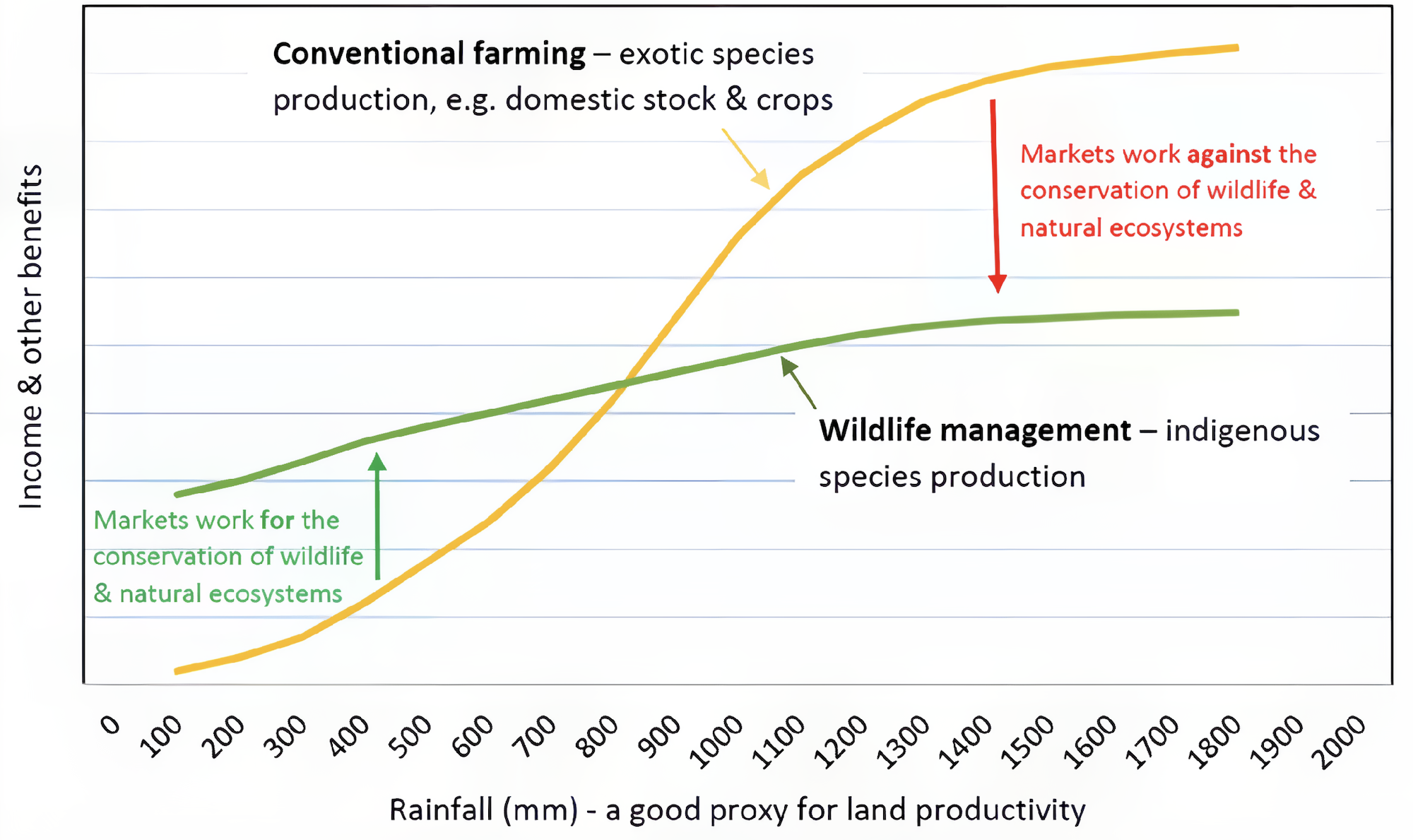

Unlike conventional livestock farming, indigenous wildlife species are better adapted to arid environments and require fewer resources like water and supplemental feeding. Further, service industries such as ecotourism, trophy hunting and live sale of high value species add value to wildlife far beyond its meat. Further, all of these wildlife uses, including meat production, can be practiced in the same area, thereby optimising sustainable wildlife production and the wildlife economy. This is what makes wildlife farming a better farming alternative than livestock farming, particularly in arid areas that are marginal for livestock.

Barriers to the wildlife economy: fences and human-wildlife conflict

Although wild animals demand fewer resources, they need to move across wider areas than livestock to survive, especially during droughts. Fences are major obstacles to free wildlife movement and adaptability, especially in dry areas where rainfall is erratic and resources are scarce. Smaller fenced game ranches overcome this problem by providing supplementary feed for their wildlife, but this situation is not ideal for the ecosystem. On the other hand, game-proof fencing helps prevent human-wildlife conflict caused by wildlife escaping onto livestock farms, plays a role in disease prevention, and protects valuable wildlife from poaching and predation.

In the past, indigenous pastoral communities like the Ovahimba practiced nomadic cattle herding, migrating in response to seasonal rainfall patterns and thus using the same climate adaptation strategy as wild animals. Most modern-day communal farmers have abandoned the migratory approach in favour of settling in fixed locations and using some low livestock fencing to manage their grazing lands. However, this shift has compromised their resilience to droughts and caused considerable damage to the rangeland.

On commercial livestock farms, fencing (often low fences that wildlife can jump over or crawl under) is used to control the movement of livestock, enabling micro-level rotational grazing and safeguarding grazing camps during drought conditions. Fences are also recognised for their effectiveness in controlling certain animal diseases. For instance, Namibia's commercial beef industry is shielded from Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD) by the extensive veterinary cordon fence that spans the country for 1300 km and forms the southern boundary of Etosha.

The Veterinary Cordon Fence (VCF) was erected in colonial times to separate disease-carrying wildlife and livestock owned by communal farmers in the north from the commercial farms south of the VCF. This resulted in two things: 1) wildlife being cut off from migratory routes, and 2) people north of the fence not being allowed to market their livestock south of the fence (or overseas) and thus getting lower prices for their livestock.

The VCF is still used to control disease transmission today and plays a role in reducing human-wildlife conflict south of Etosha. However, communal farmers now have a political voice and are increasingly advocating for its dismantlement. This push stems from both its economic impacts and its association with colonialism. Furthermore, research from the ORYCS project shows that elephants frequently damage the fence, which allows them and other species to cross onto farmlands, leading to human-wildlife conflict on some farms and tourism opportunities on others that are set up for tourism.

The wildlife economy: Namibia’s climate change solution

Things are changing, however, as an increasing number of commercial farmers in the Etosha landscape and elsewhere in Namibia have transitioned away from livestock towards wildlife ranching, leading to a shift in their perception of wildlife and reduced conflict. Additionally, communal conservancies have provided a platform for communal farmers to derive benefits from wildlife, although their primary occupation remains livestock farming.

Hauptfleisch and colleagues interviewed 20 commercial and 10 communal farmers in their study area to obtain their views on wildlife. All of the interviewees were pleased to see giraffe, gemsbok and springbok on their land, but over half of them did not welcome the presence of spotted hyaena, elephant and leopard. However, the commercial wildlife ranchers in the sample (i.e. those that have switched entirely from livestock to wildlife) were much more positive towards the elephants and predators than the livestock farmers.

The owners and managers of large private wildlife reserves actively embraced all of these wild animals due to their potential to attract tourists and generate revenue. However, the commercial farmers that own smaller fenced game ranches still perceive elephants as a problem because they break fences and other infrastructure.

In contrast, communal farmers lack fencing susceptible to elephant damage, and with tourism present in conservancies, their attitudes towards wildlife tend to be less extreme (in either direction) than those on commercial farms. Nonetheless, the challenge of elephants damaging water sources and carnivores preying on livestock persists, thus reducing tolerance for these species on communal lands. Hauptfleisch’s research continues in the greater Etosha West and South landscape, now focusing on the biodiversity economy through support from the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ).

Namibia’s future: hot, dry and prosperous?

The future of Namibia is hotter and drier, posing challenges for livestock survival while increasing the necessity for wildlife to migrate further. Adapting to this future climate could require Namibian farmers to learn from the strategies they used in the past, before the country was crisscrossed by fencing. This can be combined with the modern wildlife economy that generates income via multiple different wildlife uses.

By fully developing the wildlife economy across large landscapes, particularly within communal and freehold conservancies and privately protected areas linked to national parks, farmers can adapt by transitioning towards wildlife-based activities, thus mitigating the impacts of climate change on local livelihoods. Despite its cultural significance, livestock numbers are likely to decline in communal areas due to increasingly severe droughts, although cattle, sheep and goats are unlikely to disappear entirely. As the cattle industry contracts and the wildlife economy expands the VCF may eventually become obsolete, prompting authorities to dismantle it, or move it northwards in incremental steps. Moreover, as wildlife becomes more economically beneficial, human-wildlife conflict is expected to decrease, mirroring trends observed in private reserves.

Namibia's growing wildlife economy presents a promising route toward climate resilience and sustainability. Reducing the number of game-proof fences and opening up larger landscapes for wildlife will be an important part of this journey. Livestock farming will continue to play an important cultural role even if its economic importance declines. Consequently, there will always be a need to reduce human-wildlife conflict by protecting livestock from predators and key infrastructure from elephants. While Namibia’s future is hot and dry, it can also be wild and prosperous.

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.