Are Namibia's Carnivores at Risk?

The new Red Data Book for Namibia

By Namibian Chamber of Environment

9th August 2019

The world is facing an extinction crisis. According to the Living Planet Index, wildlife populations have declined by 60% in the last 40 years. Although species go extinct naturally, mankind’s impact has accelerated the rate of extinction to up to 1,000 times faster than the estimated natural rate.

Our world’s plants and animals are of incalculable value as they

provide ecosystem services that are essential to life on earth. Besides

their direct worth, wildlife is valuable to us in many ways that cannot

be expressed in dollars and cents – the majesty of an elephant in

a savannah, the hard stare of a lion when you make eye contact, our sense

of serenity and wellbeing in natural spaces. These are things that money

cannot buy, but we could lose them if our conservation efforts fail.

The first step to addressing a problem is to understand its extent, severity

and causes. Without this information it would be impossible to find effective

solutions. To address this need, the International Union for Conservation

of Nature (IUCN) established the Red List, which since 1964 has grown to

become the largest and most comprehensive database of extinction risks

to plants and animals.

By combining hard data with expert knowledge in a standardised and globally

recognised format the IUCN Red List has become the go-to resource for conservationists

and the general public. It is an especially useful guide for setting conservation

priorities by identifying which species need the most urgent help, and

what we can do to reduce the threats they face. You can search this database

to find out more about plants or animals that interest you at www.iucnredlist.org.

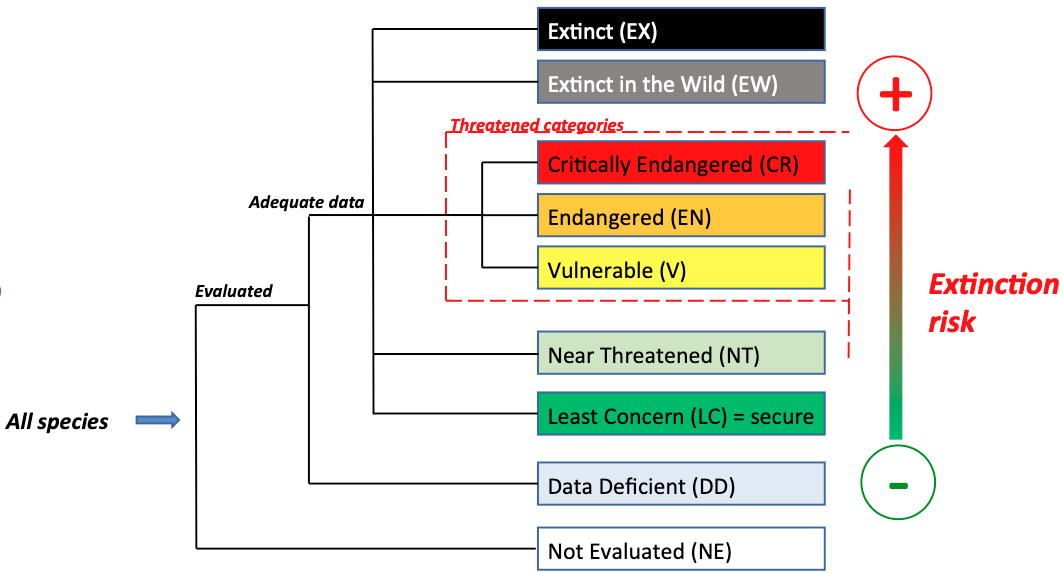

When assessing a species, experts consider more than just the total number

of animals left on earth. They take into account whether or not these numbers

have declined in the last ten years, and if so, by how much; the extent

and quality of the area they now occupy, and if that area is smaller or

more fragmented than it used to be; current population estimates; and ultimately

their probability of extinction in future. Once these factors have been

taken into account, experts assign the species to one of the IUCN categories

of threat – known as the species’ status.

Besides species that are now extinct in the wild, or those we know too

little about to assess, all others fall into one of the following categories

(from worst to best status): Critically Endangered, Endangered, Vulnerable,

Near Threatened, and Least Concern. Conservationists are most concerned

about species falling in the first three of these categories, which face

high to extremely high risks of extinction in the wild. Near Threatened

species still warrant monitoring, as these species could decline into one

of the worse categories in future if we fail to address the threats they

face today.

The Red List is concerned with global extinction risks, but this is not

always useful for governments and conservation organisations working in

specific countries – species that are doing well globally may be

declining within a country, or vice versa. If an increased national extinction

risk is not identified and addressed, individual countries may lose these

species before they are aware of the problem. Consequently, the IUCN has

created a system for assessing extinction risks at national and regional

scales. The information produced from collecting data and drawing on local

expert knowledge is then published as a Red Data book. These books are

available to the public and can assist national governments to set their

conservation agendas. A good example is Namibia’s Red Data Book

for Birds, entitled Birds to Watch in Namibia – Red, Rare and Endemic Species,

which can be downloaded from Namibia’s Environmental Information Service.

Namibia has not yet produced a Red Data book for any of its mammals, but

the Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE), together with the Large Carnivore

Management Association of Namibia (LCMAN) and the Ministry of Environment

and Tourism (MET), are looking to change this. On 8-10 November 2017, NCE

facilitated a meeting sponsored by B2Gold Namibia at the Otjikoto Environmental

Centre to look at creating a Red Data book for Namibia’s carnivores.

The experts who attended the meeting are affiliated with LCMAN, NCE and

MET, organisations that are ideally placed to undertake collaborative tasks

such as this one.

During the conference the carnivore experts presented their current knowledge

on everything from lions to mongooses. Large carnivores, like the big cats,

hyenas, and African wild dogs, are generally better-studied and understood

than small carnivores, but they are under much greater threat due to human

pressures. During the conference the experts gave preliminary Namibian

statuses to all of the carnivores, which will be revised once all available

data have been collated and analysed for each species. These preliminary

statuses indicate that African wild dogs, cheetah, and spotted hyena have

greater extinction risks in Namibia than they have globally (see Table

1).

Table 1. The Global and preliminary Namibian statuses for carnivores. Species not listed here are classified as Least Concern globally and in Namibia.

| Global status | Common name | Namibian status |

|---|---|---|

| Endangered | African Wild Dog | Critically Endangered |

| Vulnerable | Cheetah | Endangered |

| Vulnerable | Lion | Vulnerable |

| Vulnerable | Leopard | Vulnerable |

| Vulnerable | Black-footed Cat | Vulnerable |

| Least Concern | Spotted Hyena | Vulnerable |

| Near Threatened | Brown Hyena | Near Threatened |

| Near Threatened | African Clawless Otter | Near Threatened |

| Near Threatened | Spotted-necked Otter | Near Threatened |

One of the reasons for the large carnivore status differences between

Namibia and the rest of Africa is that their range and population densities

are naturally limited by Namibia’s dry climate. For example, spotted

hyenas are more common in high rainfall areas and are not as well adapted

to desert life as brown hyenas. Namibia’s spotted hyenas therefore

occur at relatively low densities, which increases their risk of extinction

when compared to other spotted hyena populations.

African wild dogs are also confined to the wetter parts of the country

(the northeast), but they are more susceptible to being killed by farmers

than hyenas. The dogs are more visible as they hunt in packs and can be

active during daylight hours, while their use of communal dens makes them

vulnerable to farmer retaliation. Wild dogs are perceived to be incompatible

with livestock farming, which means that if farmers find their dens, they

can eliminate a whole pack in short order. Changing the perceptions and

subsequent tolerance of farmers for wild dogs is thus a conservation priority.

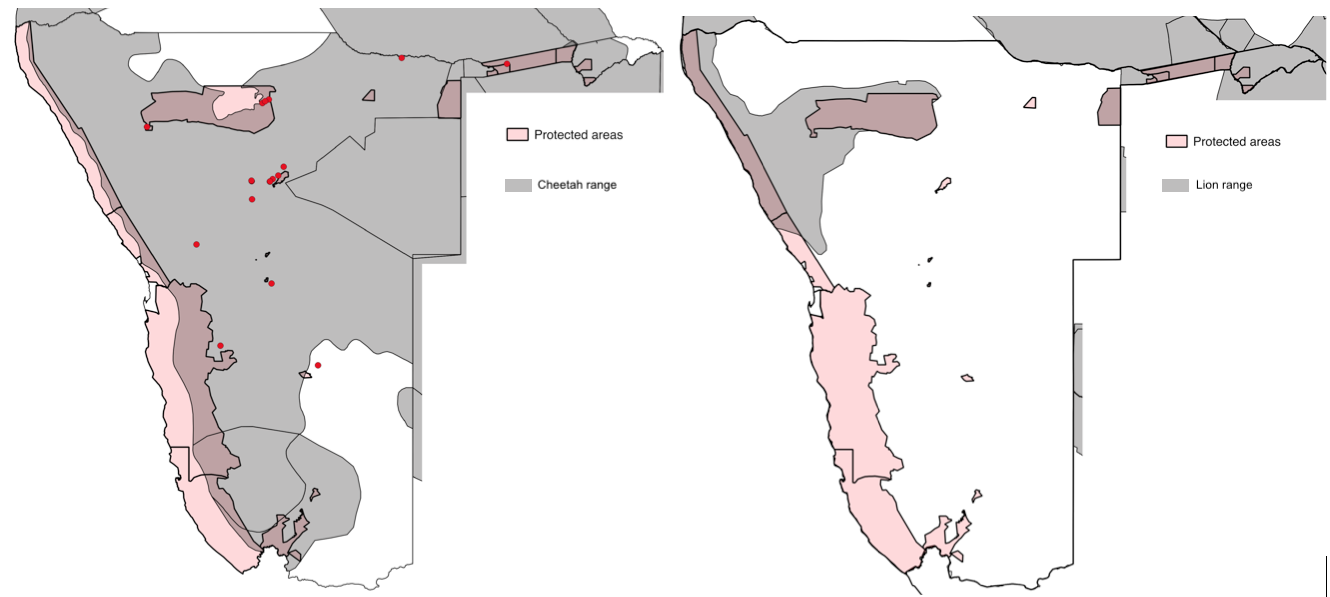

Cheetahs are also under threat in Namibia, largely due to their conflict with livestock and game farmers. Despite Namibia co-hosting the largest population of cheetahs in the world with neighbouring Botswana, the vast majority of these cats occur on farmland that has no official protection status. There have been two recent calls [1, 2] to up-list the cheetah to Endangered globally, which will match the status given for Namibia. Currently cheetahs and livestock farmers coexist to some extent in Namibia, particularly in areas with healthy wild prey populations. Game farmers tend to be less tolerant of cheetahs, as these cats are efficient predators of their preferred prey species – e.g. springbok, blesbok and the young of larger, often high-value antelope.

In stark contrast to cheetahs, Namibia’s lions are almost entirely reliant on protected areas like Etosha, and they are rarely tolerated by farmers. The main exception to this rule is the population in the far northwest, where lions occur at naturally low densities due to the harsh desert environment. Farmers in these regions come into conflict with the lions, but several concerted conservation efforts from government, non-governmental organisations and local conservancies have contributed to keeping this unique population alive.

Leopards are more broadly distributed within Namibia than either cheetahs

or lions, but their Vulnerable status indicates that they remain a conservation

concern, perhaps more so at the global level than in Namibia. The smallest

cat in Namibia – the black-footed cat – shares its status

with leopards, and poses even greater challenges to scientists trying to

study it. Leopards are difficult to count due to their secretive, nocturnal

nature, and black-footed cats are even worse! Both cats are secretive and

nocturnal, but whereas leopards can be counted using heat and motion-sensitive

camera traps, black-footed cats are rarely caught on camera.

In the process of writing the Red Data book carnivore experts in Namibia

will access as many sources of reliable information as possible. Carnivore

researchers conduct intensive surveys using camera traps and other methods,

but these efforts are usually limited to specific study areas and time

periods. Furthermore, small carnivore species (e.g. mongoose species, honey

badgers and weasels) are rarely surveyed so intensively. While intensive

studies provide the cornerstone of our data collection efforts, more data

over a larger area of Namibia and over longer time periods are required

to improve the accuracy of the extinction risk assessments.

The good news is that anyone who lives in or visits Namibia can contribute

by becoming a ‘citizen scientist’ and collecting data for

scientific purposes. Today you can do this very easily by getting the free

Atlasing in Namibia Application developed for smartphones. This app

contributes to the Namibian Environmental Information System, an online

database that hosts a mind-boggling amount of information about the country.

After downloading the Atlasing app you can report any sightings of carnivores

and a range of other animals and plants in a matter of seconds. The app

uses your smartphone’s built-in GPS unit to provide an accurate

location for your sighting, and you can even submit photos if you are unsure

of the species’ identification. If you are not online when you record

the sighting, the app will save your records and upload them when you choose

to do so. Once you have entered and uploaded your sightings, you can visit

www.the-eis.com/atlas to find your own and others’ contributions

to the database on a map of Namibia.

The global extinction crisis is real. Nonetheless you can help dedicated

wildlife researchers collect accurate information on species that are under

threat. This knowledge is power, which will be used to guide our conservation

actions and prevent further human-caused extinctions. Get the Atlasing

app, and become part of the solution.

References:

1. Weise, F.J. et al. (2017) The distribution and numbers of cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) in southern Africa. PeerJ 5:e4096 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4096

2. Durant, S.M. et al. (2016) The global decline of cheetah. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 201611122; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1611122114

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.