Taking a scientific approach to pangolin conservation in Namibia

9th September 2021

The pangolin has gained unwelcome notoriety in recent years as the world's most trafficked mammal, yet pangolins are severely understudied and their ecology mostly remains a mystery. For the few people who have ever seen these elusive animals, they look reptilian or even prehistoric. Pangolins are in fact the only scaly mammal. Eight species are found worldwide, four are in Asia and four in Africa. In Namibia we have the Temminck's ground pangolin, the only species adapted to an arid environment and found in southern Africa.

Pangolin trafficking in Africa is on the rise, as their scales and meat are sought after in China and other Far Eastern countries. Namibia has not been spared from the global trafficking scourge. Since 2016 there have been over 496 arrests, and in the past few years more pangolin-related cases have been opened than for rhino and elephant poaching combined. In only four years, Namibian authorities have confiscated 128 live pangolins and 268 skins or carcasses. The live pangolins are rehabilitated and released back into the wild.

Given the high numbers of live pangolins confiscated from illegal traffickers, Namibian conservationists realised that we needed to know more about the pangolin's ecological requirements to inform our releases. Research from better-known mammal species like carnivores shows that translocating an animal from one place to another is not always successful. Yet pangolins were being confiscated from traffickers, rehabilitated and released into areas that were probably far from where they were initially caught. The lack of information on what makes an ideal pangolin release site and what happens to them after release was thus a major concern for the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) and non-governmental partner organisations that jointly established the Namibian Pangolin Working Group (NPWG).

To help answer these questions, I focused my Master of Science (M.Sc.) research on pangolin ecology that included individuals found in the wild and those that were confiscated from traffickers, rehabilitated and released into the wild. My academic supervisors and I were especially interested in answering three key questions: 1) How large is the area that pangolins need for their home ranges? 2) What species of prey do they prefer? 3) What kind of burrows do they prefer to use for refuge? Tracking the released pangolins also revealed how successful the releases were in terms of survival and reproduction. Answering these questions would ultimately help to prioritise release sites for live confiscated pangolins and improve their chances of post-release survival, which fitted perfectly with the concerns highlighted by the newly established NPWG. Due to security concerns, I cannot reveal exact pangolin numbers or give specific locations, but there are some interesting results that I can share from my work thus far.

How much space does a pangolin need?

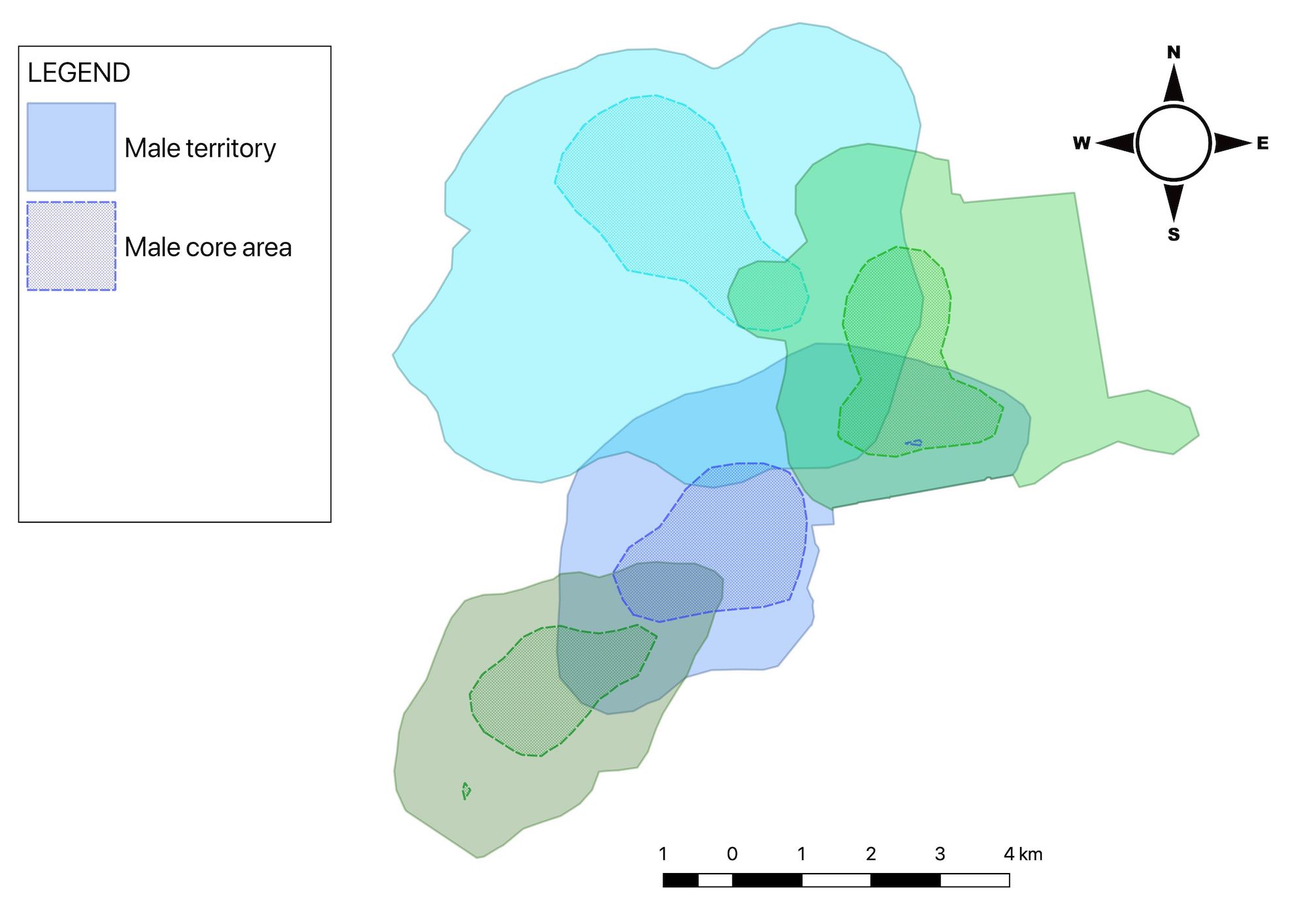

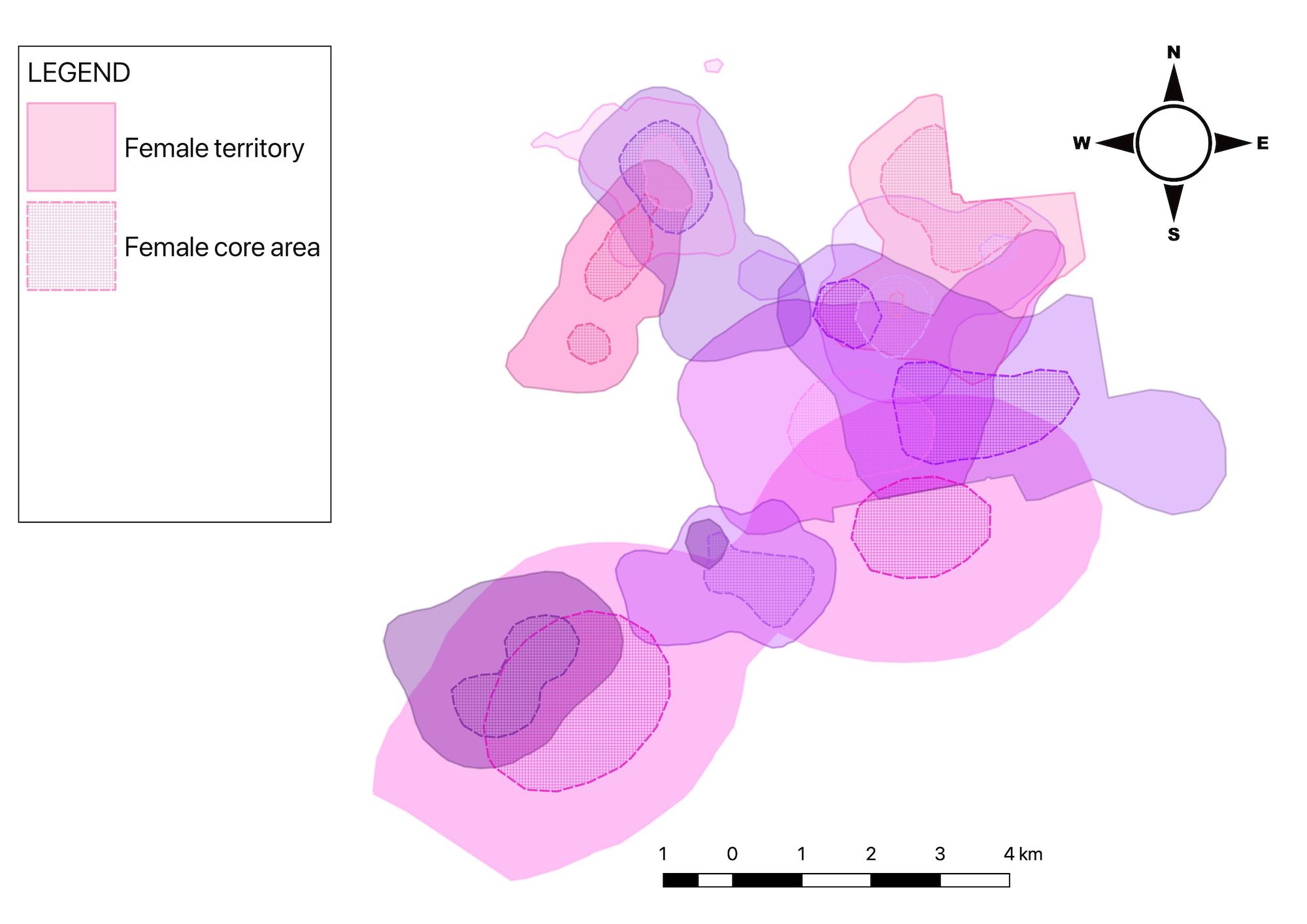

To answer this question, we tagged resident and released pangolins with radio and GPS transmitters during 2018-2020. With a radio (or VHF) tag, the research team must locate the pangolin using a receiving antenna as often as possible, but this limits our knowledge to the times when we go out and find them. Later on in the study, extra funding allowed us to attach GPS transmitters to some individuals to collect movement data more frequently and measure the ambient temperature. The resulting data were analysed and mapped for the entire study period (see map), and separated for different seasons.

We found that the average male home ranges (17.07 km2) were over three times larger than female home ranges (5.51 km2) and male core areas (i.e. where they spend 50% of their time) were nearly four times larger (6.31 km2) than female core areas (1.65 km2). A home range or territory is defined as the area where the pangolin spends 95% of its time, while the core area is a smaller part of the home range where it spends 50% of its time. Pangolins have a polygamous mating system with one male's territory overlapping with multiple female's territories. The males move throughout this area visiting and re-visiting the different females over time.

Both sexes are territorial and use their scent or anal glands to mark their territories; they also drag their tail through their urine or faeces to disperse their scent. On a number of occasions we observed territorial fights between same-sex individuals. These disputes sound very dramatic – like medieval knights clashing their armour. Despite appearing to us as docile creatures, they can seriously injure one another in these fights by thrashing their tails and pulling at the opponent's scales with their sharp claws. Unfortunately, one released pangolin succumbed to his injuries after fighting with a resident male. Other pangolins that were released at this site were similarly unsuccessful in establishing home ranges, most likely because this site already has a healthy population of residents, leaving little to no space for new individuals.

By contrast, a confiscated female pangolin that was released on a cattle farm in eastern Namibia in July 2020 settled into a territory near the release site and has established a home range of comparable size to that of residents. Excitingly, during a follow-up visit we found a male pangolin pursuing her. We therefore set up camera traps at her known burrows in the hope of recording the birth of a pup, which would be a truly successful release.

What do pangolins eat?

We already know that pangolins only eat ants and termites, using their exceptional sense of smell to locate nests where they are rewarded with larvae and eggs. Only rarely do they feed on adults encountered on the surface. Research in South Africa and Zimbabwe found that pangolins are very picky eaters in terms of which species of ant or termite they eat. We wanted to find out what Namibian pangolins ate and whether they had similarly narrow diet preferences.

To record what species of ant and termite were available in each study area, we set pitfall traps for insects across known pangolin territories. We then took samples of the species we saw our study pangolins feeding on to find out what they preferred. Dr. John Irish, a prominent entomologist in Namibia, identified our ant and termite samples to the species level. We discovered that Namibian pangolins are picky indeed – they only ate four out of the 24 identifiable species of ants and two out of the five species of termites that were found in their home ranges.

The pangolins we observed fed on ants 82% of the time, although the species that they preferred were not the most commonly found ants in our pitfall traps. Two species of pugnacious ant (Anoplolepis spp.) were especially high on the pangolins' menu, as they made up 77% of the observed diet, while the snouted harvester termite (Trinervitermes sp.) accounted for 16% of the diet. Two other ant species and one termite species accounted for the remaining 7% of our study animals' diets.

Where do pangolins hide out?

Although we know very few of the pangolin's specific habitat requirements, we do know that they need burrows as refuges during the day and safe places to give birth. Much less is known about what makes a good burrow for a pangolin. We therefore selected 151 burrows to measure in terms of height, width, internal and external temperature, general characteristics and surrounding habitat type. Only 89 (59%) of these burrows remained intact during the rainy season and could therefore be measured when we visited them after the rains. Most of the intact burrows belonged to females, which might indicate that females are better at selecting stable burrows.

Most (79%) of the burrows we measured were deeper than one metre and had a median internal burrow temperature of 14.8 °C. These types of burrows are often dug by other species such as aardvark, porcupine and warthogs. These results suggest that burrows over a metre deep are particularly suitable for pangolins. One likely reason for this is that pangolins are not good at thermo-regulation. Deep burrows remain at a constant temperature across the seasons – warm in winter and cool in summer – thus providing ideal pangolin hideouts.

Finding suitable pangolin release sites and further research

The most immediate application for my research is to help find suitable release sites for pangolins caught in the illegal wildlife trade. First, one would find out whether or not the release site already has many pangolins and if there are any open areas large enough for the released animal to establish a home range (which would be bigger for males than females). Second, a survey of the local ant and termite species would reveal whether suitable prey is available or not. Third, searching for and measuring burrows would determine if the released pangolin would find sufficient refuge in the area. Meeting these basic ecological needs would greatly increase the chances of a successful release.

Having completed the research for my M.Sc., I realised that we still know far too little about this highly trafficked animal and that there are many more questions yet to be answered. Consequently, I recently founded the Pangolin Conservation and Research Foundation (PCRF) non-governmental organisation to support further research that can be applied to pangolin conservation needs. The University of St. Andrews (Scotland) and the Biodiversity Research Centre of the Namibia University of Science and Technology continue to support my research.

My efforts are part of the bigger pangolin conservation picture in Namibia. Pangolin post-release monitoring is an ongoing collaborative effort among the NPWG members to better understand the survival success of released individuals. Meanwhile, the MEFT and its non-governmental partners in the NPWG are identifying promising release sites across Namibia on private and state-protected land. This complements continued national efforts to clamp down on illegal pangolin trafficking and keep Namibia's pangolins in the wild.

This research was conducted under the supervision of Dr. Morgan Hauptfleisch of the Namibia University of Science and Technology and Dr. Monique MacKenzie of the University of St. Andrews.

Generous financial and logistical support was received from the

Namibian Chamber of Environment,

B2Gold,

Total,

the Pangolin Consortium,

University of St. Andrews,

Namibia University of Science and Technology,

AfriCat Foundation, and

Okonjima Lodge CC.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.