Communal Conservancies Cry for Help to Survive Coronavirus Perfect Storm

Communal conservancies in Namibia were established to allow rural communities to generate income and create jobs based on their natural resources – particularly through photographic and hunting tourism, harvesting indigenous plants and selling traditional crafts. While this system has been successful in Namibia (generating over N$147 million in cash and other benefits during 2018), the coronavirus has all but destroyed the sources of income that conservancies rely upon.

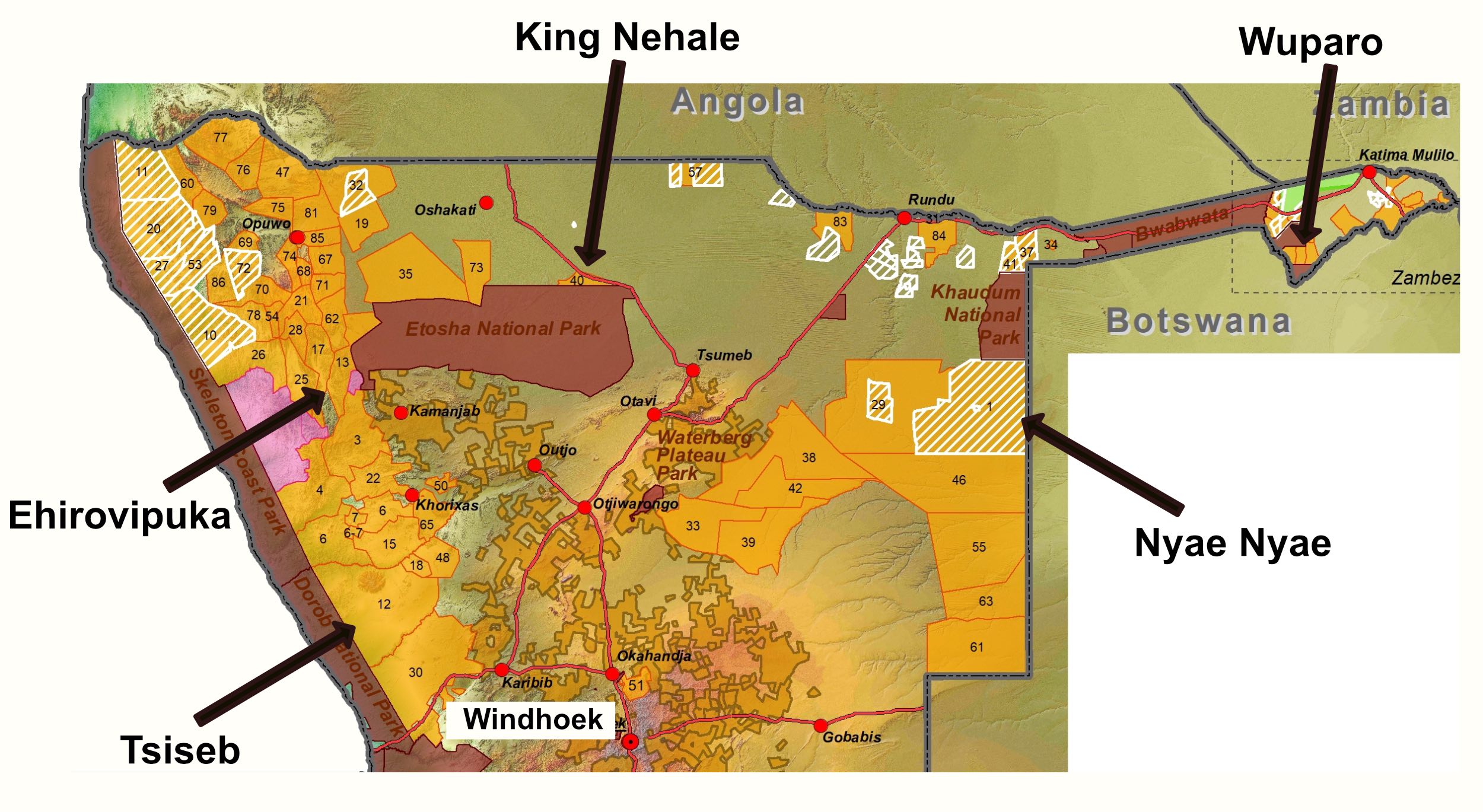

To find out more about the impacts of COVID-19 on conservancies, two researchers from the University of Namibia (Dr Selma Lendelvo and her Master of Arts student Mechtilde Pinto) teamed up with a researcher from Bath Spa University (Professor Sian Sullivan) in the United Kingdom to conduct a rapid telephone survey with management representatives and members of five communal conservancies. All calls were made during 5-15 April 2020, about one month after the first COVID-19 cases were recorded in Namibia and 1-2 weeks after the full lockdown was announced. The researchers selected conservancies from different parts of Namibia (see map) that relied on a variety of different sources of income prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. Despite their diverse locations and different natural resources, all five conservancies relied heavily on some form of income that required international visitors. The findings of this survey have recently been published in a peer-reviewed article in the Namibian Journal of Environment.

This qualitative study was designed to allow conservancy respondents to voice their main concerns and key challenges during recent lockdown conditions. Reported impacts ranged from loss of income and lack of capacity to tackle poaching and human-wildlife conflict, to severe disruptions in community benefit projects and confusion caused by lack of communication on COVID-19. When taken together, the impacts caused by COVID-19 have created a perfect storm

that conservancies will not be able to weather without external help.

All conservancy decisions are made through face-to-face meetings between management and staff, or in larger community General Meetings, none of which could continue when lockdown was announced. As a respondent from King Nehale Conservancy describes: In line with the Minister of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) directive in a letter dated 26 March 2020 to communal conservancies prohibiting face-to-face meetings (including planning meetings and management committee meetings), management has been put on hold until the situation normalises.

Cell phone signal is patchy and unreliable in rural areas and only a few people have smartphones, while those that do are unable to afford enough mobile data for Internet-based communications. While some of the managers and staff tried to maintain contact using WhatsApp or calls, it was simply not possible to get messages out to their broader membership to keep people up to date on the latest developments or to enable community participation in decision-making.

Critical conservancy operations include anti-poaching patrols, often with assistance from MEFT rangers, and monitoring human-wildlife conflict (HWC) incidents. Both of these functions were severely impaired due to communications challenges and lockdown measures. As the Tsiseb Conservancy manager reflects: HWC is increasing on a daily basis. As we speak, poaching remains a thorn in the flesh as our monitoring intensity is reduced [due to the lockdown]. Only today I attended a HWC case of a leopard that killed five goats, two dogs, two cats and some poultry in a kraal and around the vicinity of the lodge premises.

Perhaps the most severe impact that may cause long-term damage for communal conservancies is their loss of income from tourism-related industries. Several of the conservancies in this study had signed agreements with joint venture partners and hunting outfitters – private companies that manage a lodge or hunting camp in the conservancy area and pay the conservancy according to negotiated contracts. These companies have been unable to receive guests since the earliest impacts of COVID-19 were felt around the world, which will result in much lower payments to conservancies. Furthermore, people employed by the conservancies and their private partners face current salary reductions and possible retrenchments in the near future.

A respondent from Nyae Nyae explained what this means for their conservancy: “Hunting is badly affected. Presently all hunting permits have been withheld until lockdown is over. Most hunters to the conservancy are from European countries which are the most affected by the pandemic. As the lockdown continues there might be a drop to the annual income [of the conservancy] from hunting.” This was echoed by sentiments from Ehirovipuka: “As a conservancy, we are faced with cash-flow problems as our sources of income are from tourism and hunting. Due to COVID-19, our projected cash-flow will be affected. As of now we will no longer have funds for the field operation and payments of employees and the office administration. We have projected a loss of N$ 170,000 [during 2020] due to COVID-19.”

The money collected from these sources goes towards operating the conservancies and implementing community development projects as part of the benefits conservancy members receive. Many of these projects are jointly funded by an external donor and the conservancy, but these have been severely disrupted this year and the conservancies may no longer be able to afford their side of the agreement. In Wuparo Conservancy: “The pandemic has disrupted on-going projects, for instance, the water and electrification projects that were at present under construction. The disruption has been a disappointment to the members as they anticipated being able to light up their homes with electricity before the end of the year. Project extension is now inevitable and projects might take longer than envisioned as most of the financing will have been depleted through operational activities, and the possibilities of replenishing this finance are dependent on trophy hunting.”

Since these interviews were completed in mid-April, MEFT and several other partners have responded to the situation. With funding from Namibian businesses like B2Gold and Nedbank Namibia, the international institutions World Wildlife Fund, German Corporation for International Cooperation (GIZ), the KfW banking group, and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), along with substantial investment from the Environmental Investment Fund of Namibia, MEFT has set up a N$26 million emergency response fund aimed at assisting communal conservancies.

Several Namibian non-governmental organisations – the Namibian Chamber of Environment, the Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organisations (NACSO), Tourism Supporting Conservation (TOSCO) and Save the Rhino Trust (SRT) – have made special fund-raising efforts to support the community game guards, lion and rhino rangers in the conservancies. These funds will support salaries for these critical conservancy employees that focus on the twin threats of poaching and human-wildlife conflict. The response from these public and private institutions reveals that conservancies are not alone, but have an extensive support network around them that can assist them during these difficult times.

While these efforts will help conservancies weather the coronavirus storm, it is clear that the recovery of photographic and hunting tourism will be necessary for the current conservancy model to survive, so as to save the joint venture partnerships and jobs that rely on these sectors. At the same time, the pandemic might also provide pause for thought about the reliance of rural livelihoods on international visitors and associated incomes.

COVID-19 provides an opportunity to carefully assess risk and look at ways to build resilience into the livelihoods of rural communities and their ecosystem services. While the conservancy programme is itself a means of diversifying rural incomes by reducing reliance on drought-prone traditional agricultural systems, more can and should be done to further diversify sustainable livelihood options in Namibia.

Reference:

Lendelvo, S., Pinto, M., Sullivan, S. (2020). A perfect storm? The impact of COVID-19 on community-based conservation in Namibia. Namibian Journal of Environment 4 B:1-15. academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/65/3/323/236866

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

Gail Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.