Conservation Controversies: The vista from the summit of Mount Stupid is vastly different from the view from the Valley of Despair

12th November 2025

12th November 2025

Knowledge of wildlife behaviour, how animals care for their young, how they communicate with each other, and other cute and interesting facts are common in nature guidebooks, magazine articles, and safari guide rhetoric. The eco-tourism experience is about giving the animal a place in our hearts. Conversely, knowledge of ecosystem processes, energy flow, homeostasis, genetic bottlenecks, and carrying capacity is not well understood by the general public, as it is seldom explained outside of scientific writing and lecture halls. The last thing an avid tourist on safari wants to hear about is how a six-carbon sugar is converted into two molecules of pyruvate, allowing an elephant to locomote.

A love of animals, combined with a limited understanding of ecology, is possibly one of the root causes of many vitriolic debates about wildlife conservation. My teenager would call it a clap-back battle – a mud-slinging contest by camouflaged keyboard ninjas on social media. Some of the topics that incite these debates include elephant culling, trophy hunting, and alien invasive species extermination (especially if the species is a ‘cute’ mammal). I will attempt to unpack two of these topics affecting biodiversity conservation in southern Africa: trophy hunting and elephant management.

Trophy hunting and the Dunning-Kruger effect

The narrative around trophy hunting is driven by equally vociferous pro- and anti-hunting activists on social and traditional media. Meanwhile, economic and ecological statistics are hidden in scientific journals alongside thousands of unrelated writings.

A group of scientists from the University of Reading in the UK randomly selected 500 social media posts about the trophy hunting debate. They found that 350 of these opposed trophy hunting, and only 22 advocated for it. The other 128 either had a neutral view or their stance could not be determined. The general tone was unsurprisingly classified by the scientists as hostile, while 7% of the posts were classified as abusive. The posts were largely considered to be unproductive in terms of exchanging ideas and opinions. They further characterised four archetypes opposing trophy hunting: the activist, the condemner, the objector, and the scientist. Only the objector and the scientist allowed for any form of productive discussion.

The problem with social media is that information is provided in snippets of around 20 words, making it easy to retain in memory. If a reader were to digest the first 10 social media posts in the example above, it is quite likely that they would feel supremely confident about the “facts" presented, especially the persuasive ones. This leads them to steadily climb up “Mount Stupid".

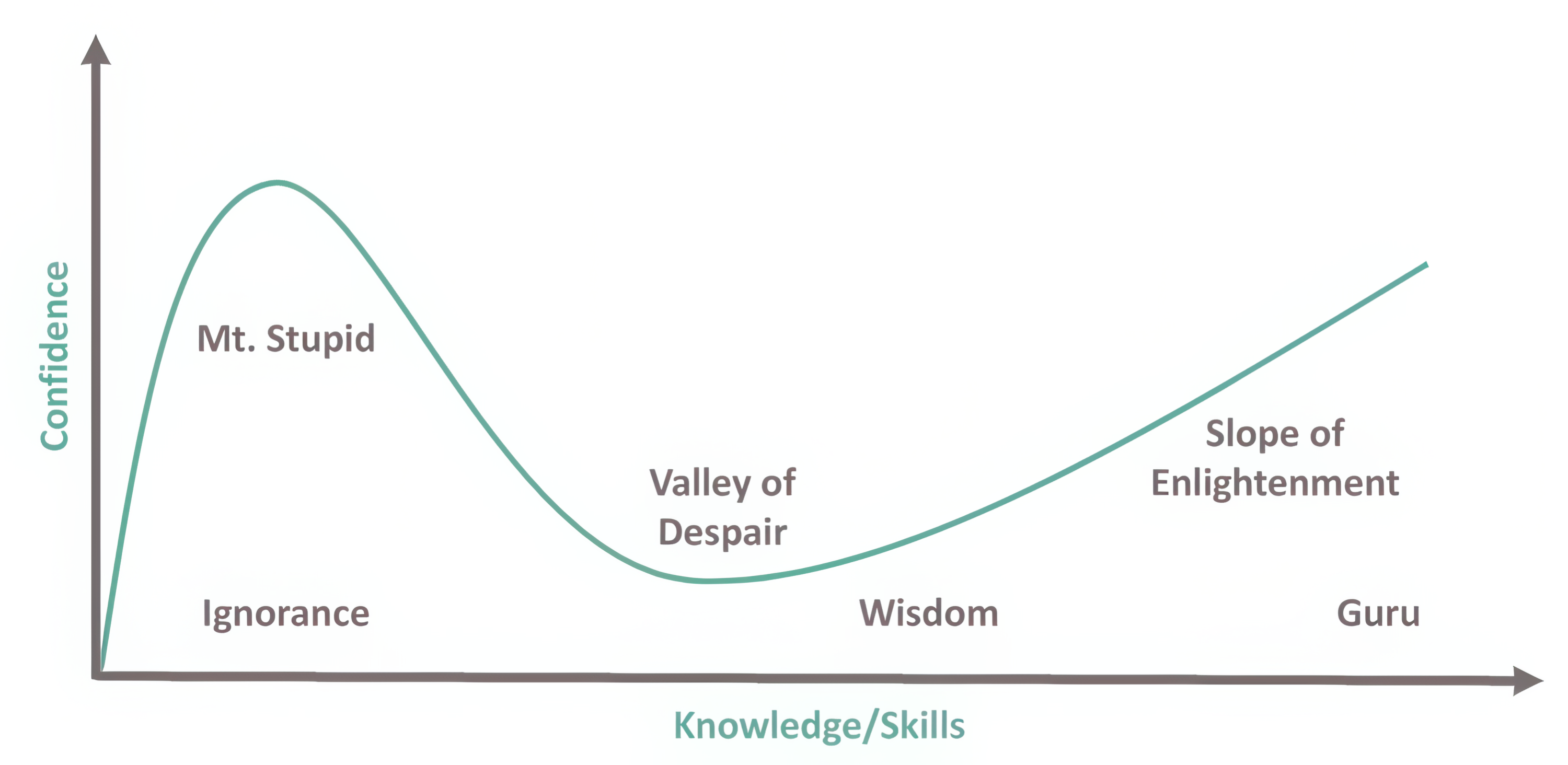

Let me explain what I mean by Mount Stupid. In 2011, two scholars of psychology – David Dunning and Justin Kruger – published their research on why people with little knowledge or competence in a particular subject are overconfident in their understanding of that subject. Their resulting graph (see below) is now known as the Dunning-Kruger effect.

The Dunning-Kruger model shows that as we move from no knowledge to a little knowledge, there is a dramatic rise in our confidence: we think that we have mastered the subject and therefore form a strong opinion. As we educate ourselves further, however, our confidence tumbles down the mountain, reaching the “Valley of Despair". Here we discover the complexity and nuance of the subject and start to realise that we know very little. Often, the scientist is clawing his or her way out of the valley, somewhere towards the “Slope of Enlightenment", but their confidence is nowhere near that of those left behind on the crest of Mount Stupid. Without trying to gain more knowledge on the subject, those on the mountain are seldom budged.

From the anti-hunter's mountaintop, it is overwhelmingly evident that the hunter poses a threat to the animal, and its demise will result in the loss of a sentient being to the earth, likely threatening the species with extinction. The act is savage and cruel, equal to murder. It is equally clear from the hunter's mountain that hunting is a sport that is good for conservation and economics and that the opposing view is elitist, idealistic, and even neocolonial.

Upon further investigation, however, the complex context of communities coexisting with wildlife can be better understood. Hunting provides job opportunities, meat, and economic benefits, which increase tolerance for the species' long-term existence. This comes at the cost of a living creature, which was wild and free until the trigger was pulled. But does the loss of that individual result in a weaker or stronger gene pool for the population? Does it affect the viability of the species? What roles do ethics, motivation, social and economic status, or other factors, play in the hunter's actions to benefit or harm conservation? These are the questions that scientists grapple with in the Valley of Despair.

One way to test the effect of an action, such as hunting, is to compare “treatment" and “control" scenarios, where the thing being evaluated is either present (treatment) or absent (control). Namibia has allowed trophy hunting since 1967 on freehold lands and 1996 on communal lands, and is therefore our treatment. Kenya outlawed trophy hunting in 1977, making it a controlled activity. In Namibia, wildlife populations have increased substantially since the 1970s, particularly outside formally protected areas where hunting is permitted. In Kenya, wildlife populations declined by 68% between 1977 and 2016.

This prompts us to ask: Does Namibia have stable or growing populations because of hunting, or does hunting occur because there are healthy wildlife populations, or is it a coincidence? To further add to the complexity, Namibia and Kenya have changed in many ways besides just allowing or not allowing hunting – human population growth, changes in legislation on related matters (e.g., land ownership), and their years of independence are just a few of the many differences between the two countries. This comparison did not happen in a controlled laboratory setting!

Trophy hunting is clearly not a topic to be judged in the court of Instagram or Hello magazine. The complexities need to be translated into hypotheses, tested, and accepted or rejected, leading to new knowledge and further scientific advancement. This should move us a little further up the Slope of Enlightenment.

Too few or too many elephants? Another case for Dunning-Kruger

Returning to the first point made in this article, elephants are one of the major attractions for tourists visiting Africa. They are the main characters in storybooks, films, and commercials. They are indeed magnificent, gentle, wise, and intelligent creatures. Any thought of interfering with their existence or population numbers through lethal means is, therefore, horrifying and inhumane to a large proportion of humans. To compound matters, only a fragment of the savanna elephant's historical range throughout Africa is still occupied by elephants today, and many subpopulations across the continent are in decline. It is, therefore, understandable that elephant-lovers on Mount Stupid believe that all elephants must be saved at all costs.

Proceeding to the opposite peak of Mount Stupid, a farmer in the Kalahari who wakes up one morning to a destroyed borehole and reservoir, flattened fences, and a stripped crop field sees a marauding herd of beasts that stole his livelihood. There may not have been elephants there in that farmer's lifetime, so he imagines that there must be far too many of them.

A debate has been raging for decades about the need to reduce elephant populations in certain parks and reserves across southern Africa. Between the 1960s and 1990s, elephants were regularly culled in Namibian and South African parks if they were thought to have exceeded the park's carrying capacity. As elephant numbers grow within parks and cause increasing conflict with humans outside the parks, culling is again becoming an option. There is, however, public sentiment that it is cruel and barbaric, and killing individuals of a species that is globally under threat goes against conservation principles.

To push the needle of knowledge and understanding of the elephant debate towards the Valley of Despair, we need to consider some complexity: if the African elephant population (see map) is considered by region or country, there are vastly different conservation management priorities in each. In many parts of West and Central Africa, elephant populations are small and isolated, with poaching for ivory being a common occurrence. Here, active preservation of each elephant, including protection against poaching, is critical.

In southern Africa, however, the situation is different. Elephant populations have increased, in some cases dramatically. In the Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA), there are over 220,000 elephants, 62% of all savanna elephants. Human-elephant conflict and loss of tree diversity and structure are the major concerns in this area. A 35-year study of vegetation in Chobe National Park documented a steady decline in riparian forest and woodland vegetation. The riverine forest disappeared completely between 1985 and 1998. There seem to be far too many elephants to maintain that ecosystem.

The focus on too few or too many might be the wrong angle. Historically, elephants were seldom confined to one area for very long. In his 1934 book Mammals of South West Africa, Captain Shortridge noted that elephants were “tireless walkers" that “cover hundreds of miles trekking backwards and forwards from one drinking place or feeding ground to another". They would gather in large numbers in areas where good rains had fallen, but only till the surface water dried up and they needed to move on. This resulted in a natural grazing rotation system, giving vegetation time to recover and reducing over-use.

In Namibia's Kunene Region, Shortridge noted that “elephants were wet season migrants to southern Kunene". Today, with borehole water available throughout the area, the Kunene elephant population has grown and become resident. Their permanent presence can be argued to be a man-made phenomenon. Increased human-elephant conflict across much of Kunene's farmland has been widely reported, and damage to vegetation is being observed.

A long-term solution proposed by the renowned elephant scientist Rudi van Aarde and others is re-establishing space and corridors for elephants to move over long distances. This is easier said than done. Africa's human population has grown from just under 285 million in 1960 to over 1.5 billion today. Is there enough space for elephants and us? Can we realistically make enough space for elephants to move as they would have historically? If there are clear overpopulations of elephants, why should culling and hunting be forbidden at the cost of biodiversity and ecosystem balance? In such cases, conservationists need to actively manage wildlife (including elephants), and all available options need to be considered, including lethal ones. In some cases, not acting quickly results in devastating habitat destruction and starvation of wildlife, including elephants.

One example is Madikwe National Park in South Africa, a 75,000-hectare fenced park surrounded by densely populated rural settlements. In 1992-93, the population of 219 elephants was thriving. Over the years, the negative effects of a growing elephant population became evident. A few were caught and relocated to other parks, but a government policy banning culling, largely driven by a fear of international uproar, meant the population continued to grow.

A drought in 2024 pushed Madikwe’s elephant-damaged vegetation over the edge. Pictures of skeletal, starving elephants hit the headlines. The NSPCA charged Provincial Park Management with animal cruelty for poor management. The elephant population has reached over 1,600 animals, which is one elephant every 43 hectares. Imagine the effect on the ecosystem. Finding a home for the excess elephants, or even the logistics of catching and relocating such a large number of animals, is impossible. It is clear that culling is needed in addition to translocations, contraception, feeding, and other options.

Conclusion

In an age where a buffet of information, opinion, facts, and lies is available, and sometimes even forced upon us, it's easy to reach Mount Stupid rapidly and condemn the actions of conservationists. To truly understand issues such as hunting or culling and make positive contributions towards preserving our biodiversity and ecosystems, we need to leave the false clarity from the mountaintop and descend into the Valley of Despair with studious and critical thought. Ultimately, science needs to regain its popularity and importance to generate targeted and objective knowledge to drive management and public education.

About the Author

Morgan Hauptfleisch is Director of Research at the Namibia Nature Foundation, Oppenheimer Generations Research Fellow in People and Wildlife, Extraordinary Professor at North-West University, and Adjunct Professor at the Namibia University of Science and Technology.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.