Deeper Trouble for the Okavango

28th October 2025

28st October 2025

The Okavango Delta and its upstream catchment, which supports hundreds of thousands of people, are under threat. While the potential for oil extraction in the catchment garners international attention, this life-giving ecosystem seems on track to quietly die by a thousand other cuts. A new report by John Mendelsohn for The Nature Conservancy reveals that threats to this system continue growing each year.

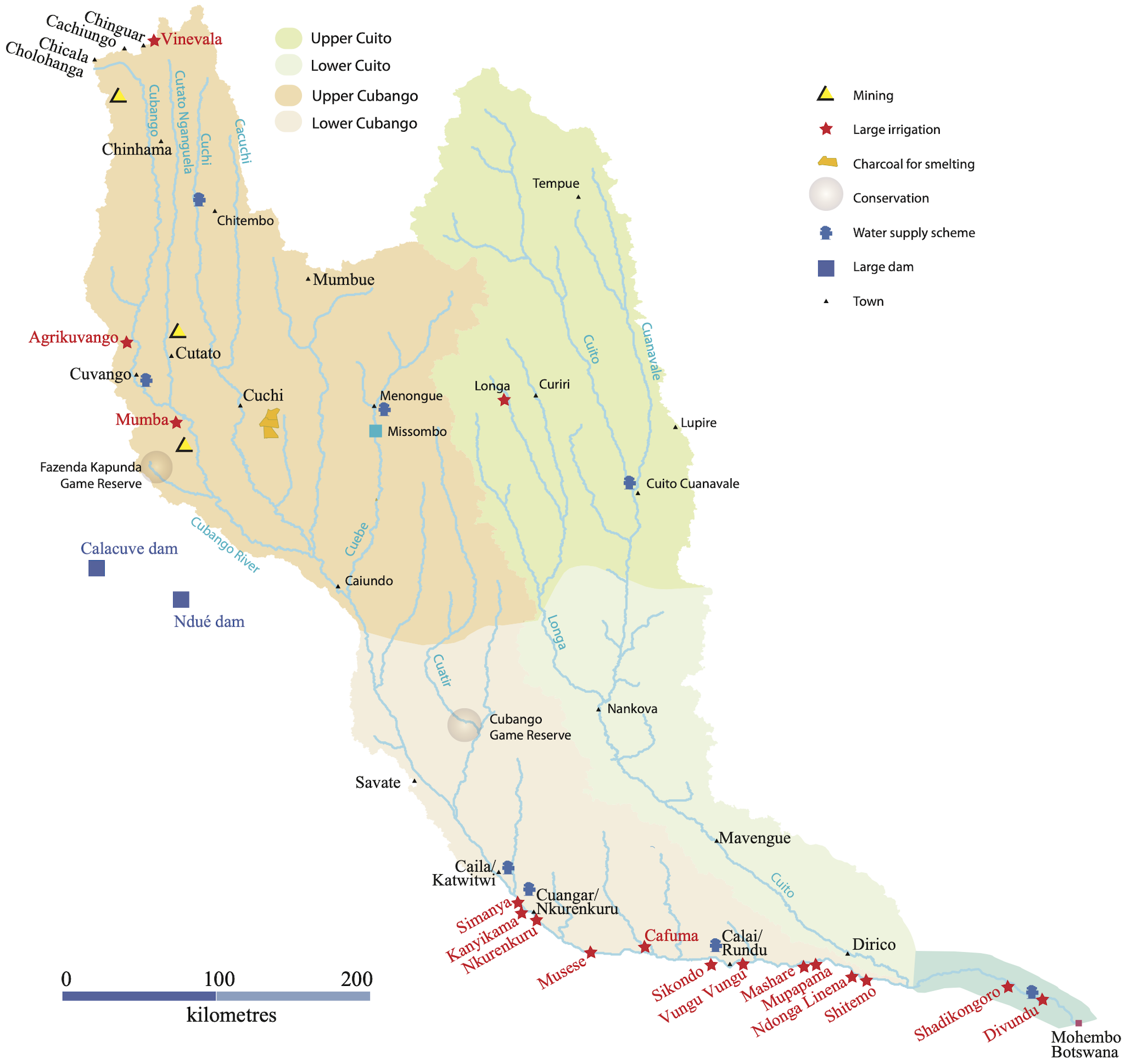

Water from Angola flows along Namibia's northern border before crossing over into Botswana, where it eventually fans out in the Delta and slowly seeps into the Kalahari sand. Two main rivers in Angola supply the Delta – the Cuito in the east and the Cubango (also known as the Kavango in Namibia) in the west.

The western Cubango River is largely responsible for the seasonal flood pulses in the rivers and Delta's floodplains that are essential for plant growth, fish spawning, bird nesting, and watering the huge number of elephants and other mammals that attract tourists from all over the world. Indeed, a substantial part of Botswana's lucrative tourism industry relies on the Cubango River and the abundance of life it supports in the Delta. Throughout its entire course, the Cubango also supports people, crops, and livestock that utilise its water and the surrounding land. Yet, if development continues in its current uncontrolled manner, the river and its ecosystem may become so degraded that the health and well-being of people and wildlife are negatively affected.

The heart of the problem lies in the inadequate management of the entire river system and its surrounding environment. Although Angola, Botswana, and Namibia established the Permanent Okavango River Basin Water Commission (OKACOM) in 1994 as a means of promoting cross-border cooperation and managing the Okavango River system, 31 years later, a formal water-sharing agreement remains absent. Controls over the use of land and water in Angola and Namibia are also virtually absent, making both land and water essentially free for the taking and use.

Consequently, commercial and subsistence developments along the river continue as though this water will never run out or become too polluted for use. Mendelsohn's 2024 report reveals that threats to this system are growing each year, with no indication that they are slowing or being controlled.

Commercial Agriculture

Commercial agriculture in Angola and Namibia along the Cubango/Kavango is expanding, but there are no controls over how much water each farm consumes, or how much fertiliser and pesticide is used. Pollution is not monitored anywhere. Between 2020 and 2024, the land used for large irrigation schemes in both countries increased from 6,200 hectares to just over 8,000 hectares. Management of several state-owned farms (known as ‘green schemes') was transferred to the profit-oriented private sector in Namibia over the same period.

While privately run commercial farms are likely to bring jobs and increase food production per hectare, these operations must be regulated. Land and water are not infinite resources. The use of fertilisers and pesticides should be controlled and limited to minimise the levels of river pollution.

Growing numbers of local residents are also commercialising their farming operations by selling their produce in towns, which allows them to invest in mechanised ploughing and fertilisers and to expand their fields. In south-eastern Angola, the rate of land clearing increased from 41.5 hectares per day in the five-year period immediately following the end of the Angolan civil war to 129 hectares per day in 2016-2020. In the most recent period (2021-23), land is being cleared for agriculture at a rate of 114 hectares per day. This development is a double-edged sword: it reduces rural poverty, but damages the land and the river.

Charcoal Production, Plantations, and Mines

Like agriculture, charcoal is produced on large and small scales. The small-scale producers sell their charcoal along roads to people living in the main towns in Angola. This may be the only source of cash income for many rural households.

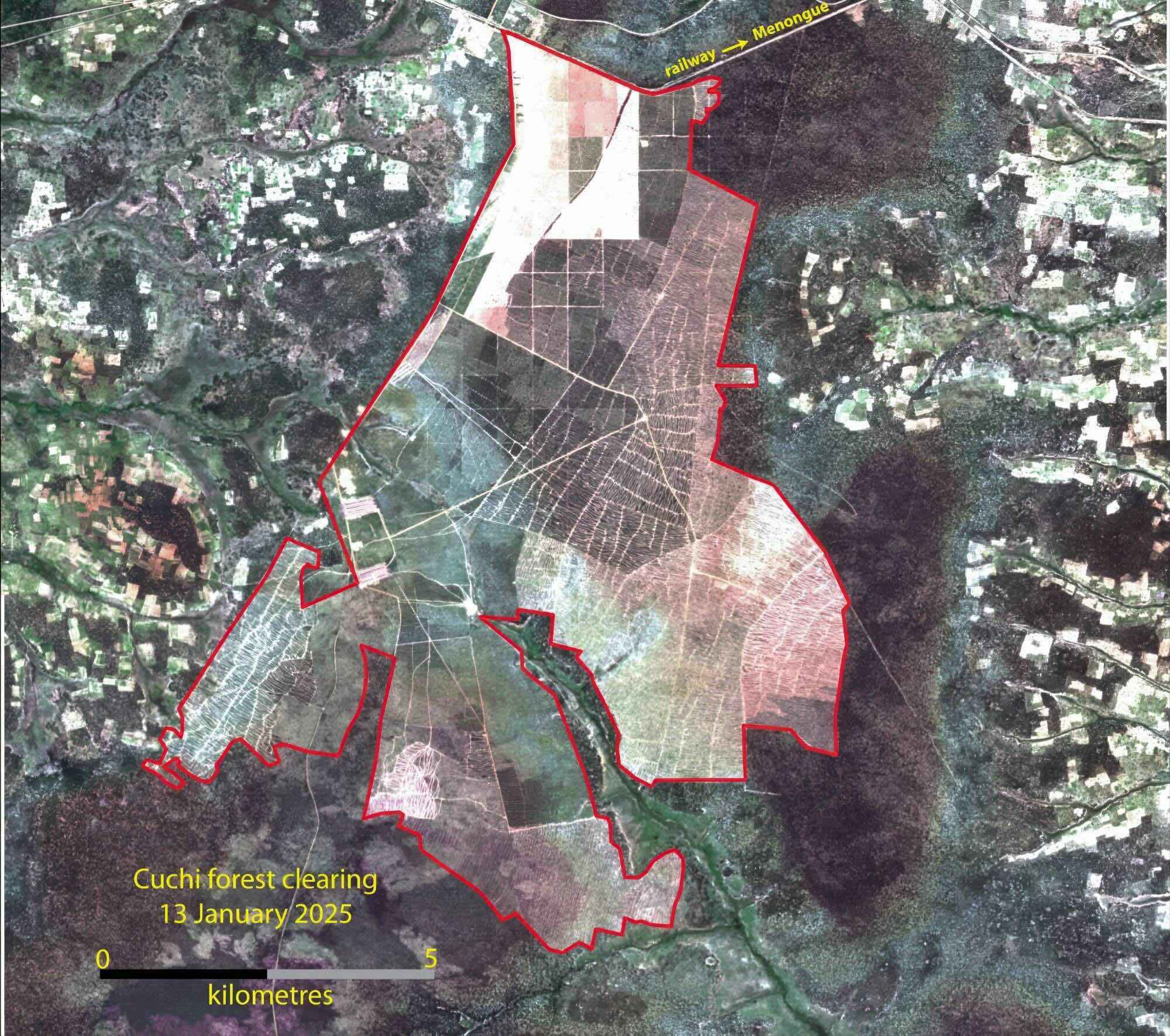

Large-scale land clearing for charcoal production is of much greater concern. In 2022, 30 farms covering 153,000 hectares were designated for clearing by a local authority in Angola. Some of these farms are already being cleared of woodland (approximately 8,400 hectares by September 2025) to produce charcoal, which is then used to smelt iron ore from a local mine. This open-cast iron mine is located within the river basin.

Ironically, the pig iron produced here is marketed and exported as ‘green' or ‘carbon-neutral' because the cleared land will be replanted with non-native eucalyptus plantations (gum trees). These plantations host very little biodiversity, are thirsty, and most other plantations like them in Angola have not grown well. Local people in this area value the natural miombo woodlands and resist the government's plans to expand these operations.

The much-publicised oil exploration in Namibia and Botswana by Recon Africa is yet another potential threat to the system. At this stage, it seems like the potential for oil in this area was over-hyped for commercial reasons, and the project is unlikely to come to fruition. Even if the exploration comes to nothing, this is a cautionary tale of how external investors can override concerns about local livelihoods and the environment. Recon Africa has recently expanded its explorations into the lower Cubango catchment in Angola.

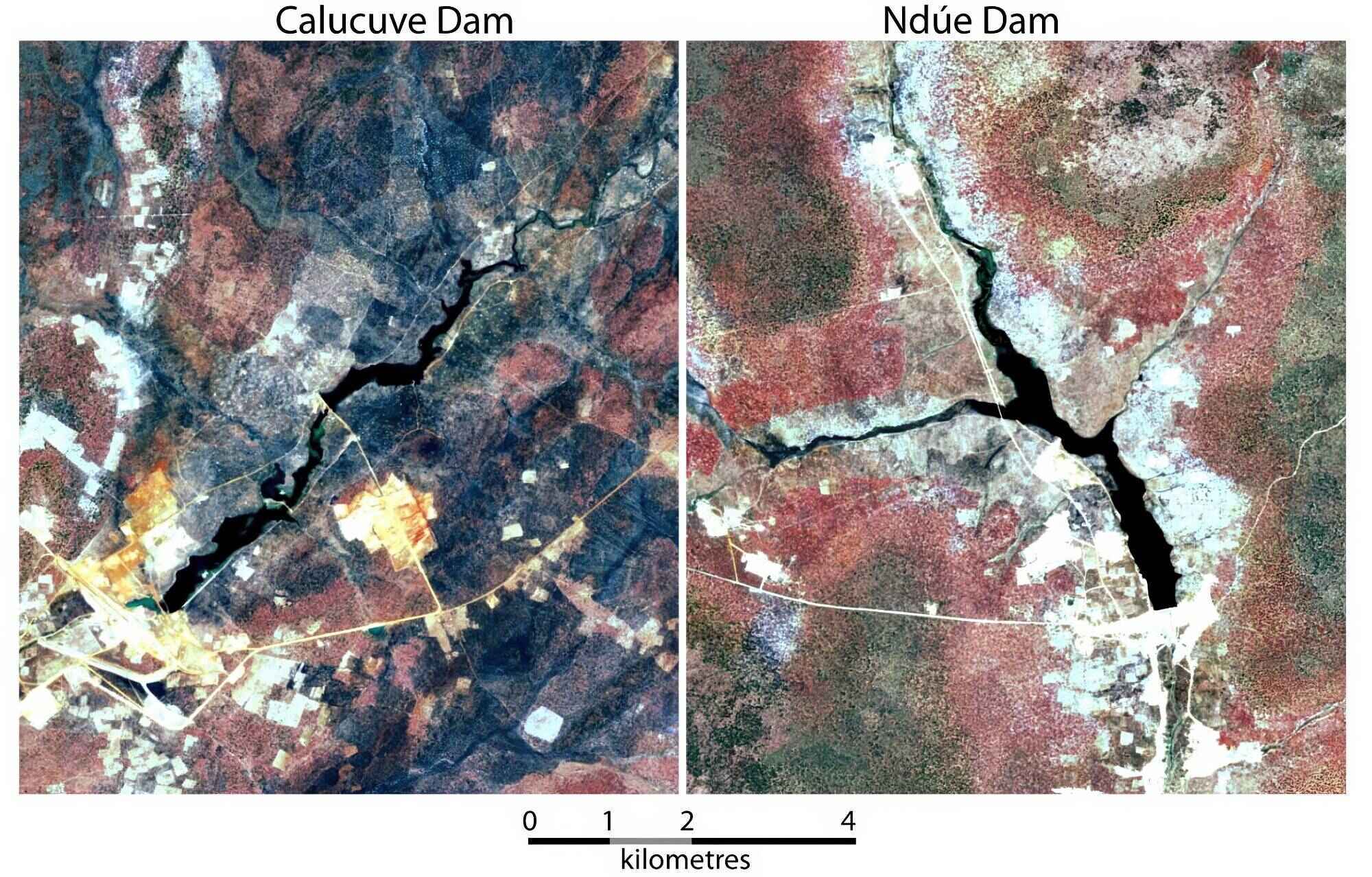

New Dams

Angola is currently building two large dams (the Calucuve and Ndué) along drainage lines of seasonal (ephemeral) rivers. Since the rainfall in this area is unpredictable and the catchment area is sandy (most water will seep away before reaching the dams), it is likely that these reservoirs will often run dry. The current plan for these dry periods is to redirect water from the Cubango River into these dams, thus taking large amounts of water from the river system.

In Namibia, plans to channel water from the Kavango River to existing dams around Windhoek are frequently proposed, especially during droughts. The current idea is to take water from the river at Rundu during peak river flow periods. Flood pulses at these peak periods are critical for the Okavango Delta ecosystem and for floodplains along the major rivers.

These plans do not account for the increased volumes of water being extracted from the major rivers in Angola and Namibia in recent years. Between 2017 and 2023, along the section of the river that forms the border between Namibia and Angola, the number of small water pipes increased from 25 to 130, the number of medium-sized pipes increased from 44 to 95, and the number of large pipes from 20 to 25 or 26. Most of these pipes are on the Namibian side of the river.

For many years, it was assumed that measurements of flow at Rundu reflected the volumes of water leaving Angola at the Katwitwi border post. New data reveal that this is not the case, and that large volumes of water are indeed lost from the Kavango River before it is joined by the Cuito River from Angola. If even more water is taken from the Cubango/Kavango by either Angola or Namibia, the effects on the Delta in Botswana could be severe.

Expansion of Towns and Cities

Migration from rural to urban areas is inevitable as both Angola and Namibia develop, resulting in larger towns that have substantial requirements for land and water. Many villages in Angola are rapidly becoming towns, while several towns are growing into cities in the catchment area of the Cubango River. This trend can have positive effects, as people living in towns have greater access to services and income opportunities than those in rural areas. The rural environment should also benefit if fewer people rely on slash-and-burn subsistence agriculture.

Urban development nonetheless poses challenges for the environment. Solid waste and sewage from towns are significant sources of river pollution, and there is already evidence that the Namibian section of the river is being contaminated by chemicals and waste generated by agriculture and urban areas.

The environmental impacts of growing urban areas can be mitigated through proper town planning, waste management, and efficient water use. Like many of the other challenges outlined here, these require strong political will, wide public awareness, and collective action to overcome.

The Key to Saving the Okavango: Public Interest and Political Will

The future of the whole Cubango/Kavango river system, including the Okavango Delta, lies with the three countries that manage and benefit from these waters. The Okavango Delta supports a thriving tourism industry that contributes substantially to Botswana's economy, but the concerns raised above are not limited to Botswana. If development continues in the unregulated “free-for-all” way that is currently happening in Angola and Namibia, people and the environment in all three countries will suffer.

With land and water so easily available, many more large, irrigated farms can be expected along the Cubango/Kavango and Cuito rivers. Consequently, downstream flows will be reduced and increasingly polluted by agricultural chemicals.

These changes and challenges are inevitable unless substantial controls and measures are implemented to minimise environmental impacts. Both existing and new commercial crop farms must use water efficiently and minimise artificial fertiliser inputs. Underground water should be used more to supply farms, towns, and other users.

Urban growth will present additional challenges, but towns that are properly managed can accommodate a large number of people and enhance their living standards without compromising the environment.

Major new developments such as dams, mines, and oil production should be approached with the appropriate levels of caution and public participation. Are the damages that such projects cause worth the economic gains that they may produce? Clearing vast swathes of biodiversity-rich miombo woodland to replace it with eucalyptus plantations is one example of ill-conceived development. The people living in the affected area will lose their natural resources and access to ancestral lands, while a private company profits from exporting green-washed pig iron.

Choosing positive development trajectories over short-term gains requires strong political will, which is driven by public concerns and understanding. The people living in Angola, Namibia, and Botswana need to be aware of the threats posed by water loss, pollution, and land degradation in their immediate vicinity and upstream.

Plans to redirect water from the river to dams in Angola and Namibia should not be implemented without consulting Botswana. The OKACOM platform, which is intended to promote co-management of the Okavango system among the three countries, needs to be active and taken seriously by all stakeholders, especially the governments of the Basin States.

The Okavango ecosystem may be known globally for its final destination – the Delta – yet this is certainly not the only reason to manage it wisely. Thousands of people live along the river and within its broader catchment area, thus depending directly on this ecosystem for their survival and well-being. Their rights to a clean, functional environment and sustainable economic development must be considered together, rather than as separate issues. It is time for the governments of these three nations to heed the ecological warning signs and chart a more sustainable path forward for their people and the Okavango River Basin.

Full Report:

Mendelsohn, J. (2025). Threats and developments in the Catchment of the Cubango/Okavango River in Angola and Namibia: Update and Perspectives in 2024. Compiled for The Nature Conservancy.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.