The State of Giraffe in 2025: A Turning Point for Africa's Tallest Mammals

10th November 2025

10th November 2025

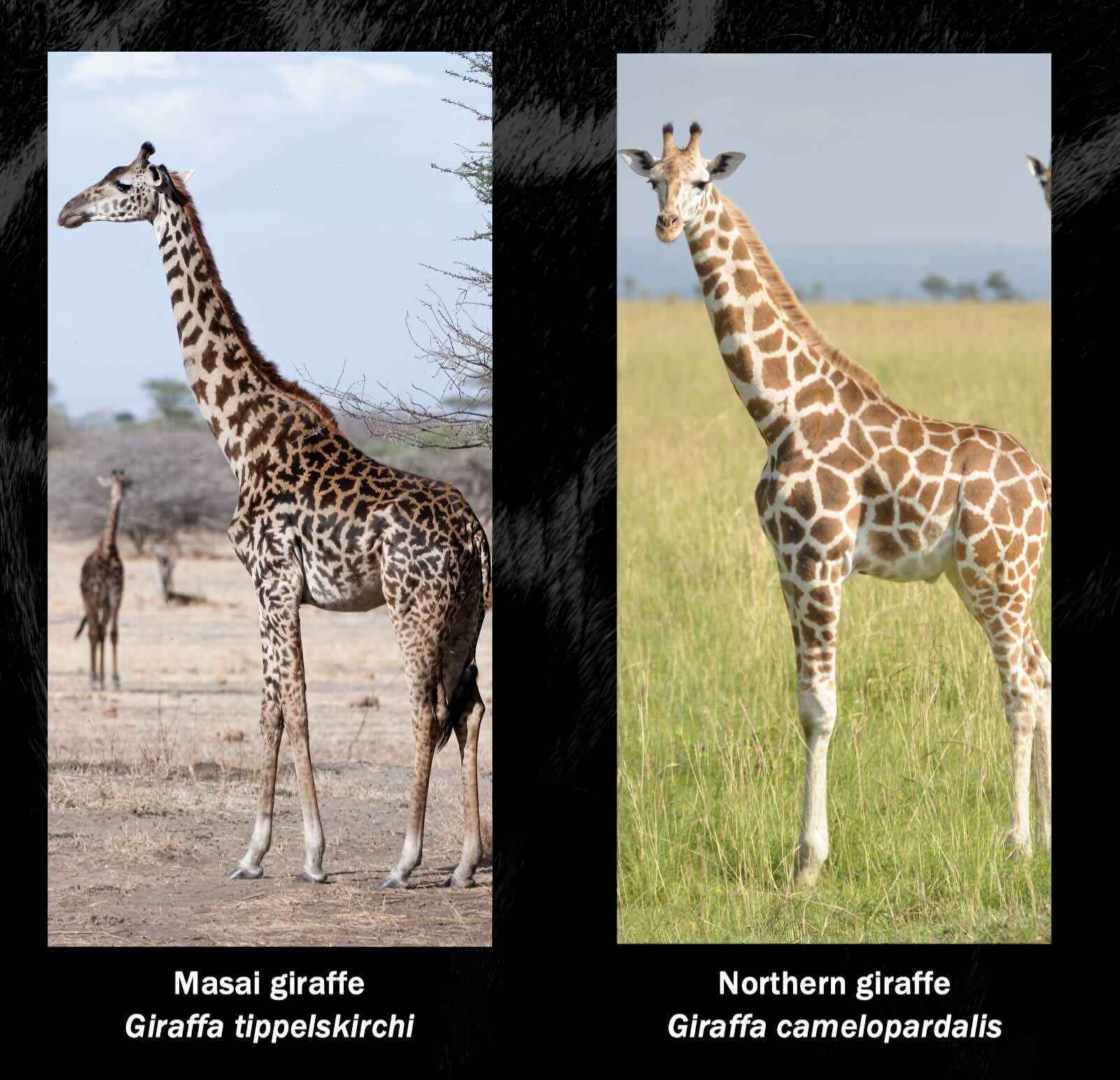

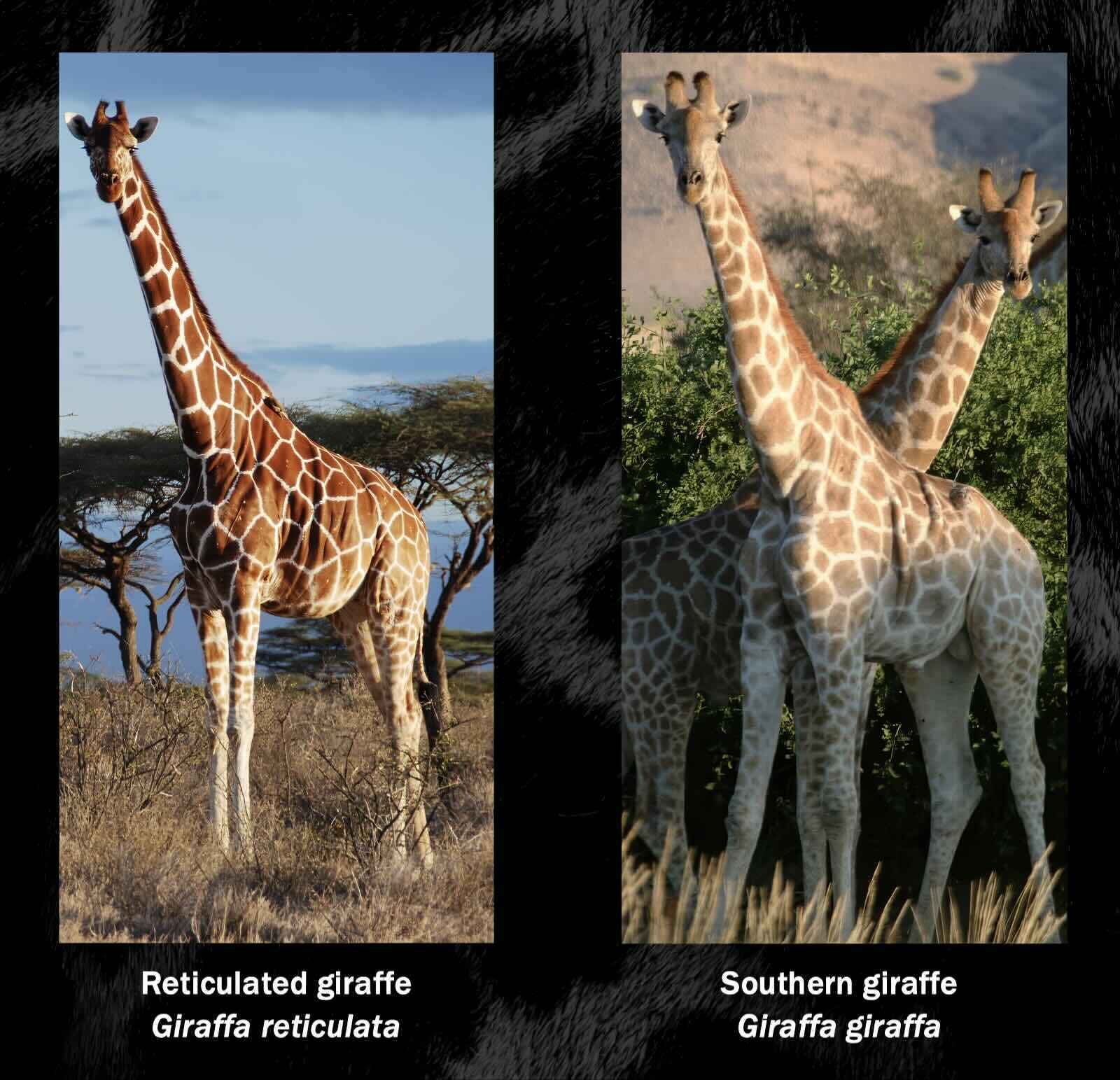

The year 2025 will be remembered as a turning point in the story of the giraffe. Long familiar as one of Africa's most iconic animals, giraffes are undergoing a transformation in the way science, conservationists, and the public understand them. For more than 250 years, all giraffes were thought to belong to a single species, Giraffa camelopardalis. That picture has now changed dramatically. In August, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) formally recognised four distinct giraffe species: the Masai giraffe, Northern giraffe, Reticulated giraffe, and Southern giraffe.

How do we know that there are four species of giraffe?

The detailed taxonomic review was conducted by the IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Giraffe & Okapi Specialist Group Taxonomic Task Force. This review evaluated extensive genetic data from multiple peer-reviewed studies. Many of these studies focused on giraffe genetics, making the giraffe one of the most genetically well-studied large mammals in Africa.

Complementing the genetic work, the review also incorporated studies of the physical form and structure of the giraffe, including notable differences in skull structure and bone shape across regions. Spatial use and biogeographic assessments also considered the role of natural barriers – such as major rivers, rift valleys, and arid zones – that could have contributed to evolutionary isolation. Together, these multiple lines of evidence provide clear scientific support for elevating certain giraffe populations to full species status, reflecting their distinct evolutionary histories.

This research was largely spearheaded by the Namibian-based Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF), in partnership with many African governments, conservation organisations, and academic institutions. Most notably, the genetics research was undertaken by GCF in collaboration with the Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre (SBiK-F). These findings, first revealed in 2016, revealed differences between giraffe lineages as deep as those separating polar bears and brown bears, an extraordinary discovery for such a visible and widely distributed animal. As Professor Axel Janke of SBiK-F remarked, “to describe four new large mammal species after more than 250 years of taxonomy is extraordinary.”

Conservation applications of the new classification

This reclassification is not simply an academic curiosity. As Dr Julian Fennessy of GCF emphasised, each giraffe species faces different threats, and now we can tailor conservation strategies to meet their specific needs.

For the first time, conservation priorities, funding streams, and international policy will be able to focus on species-specific requirements, recognising that the ecological challenges facing Northern giraffes in Niger are not identical to those for Southern giraffes in Namibia or Masai and Reticulated giraffes in Kenya.

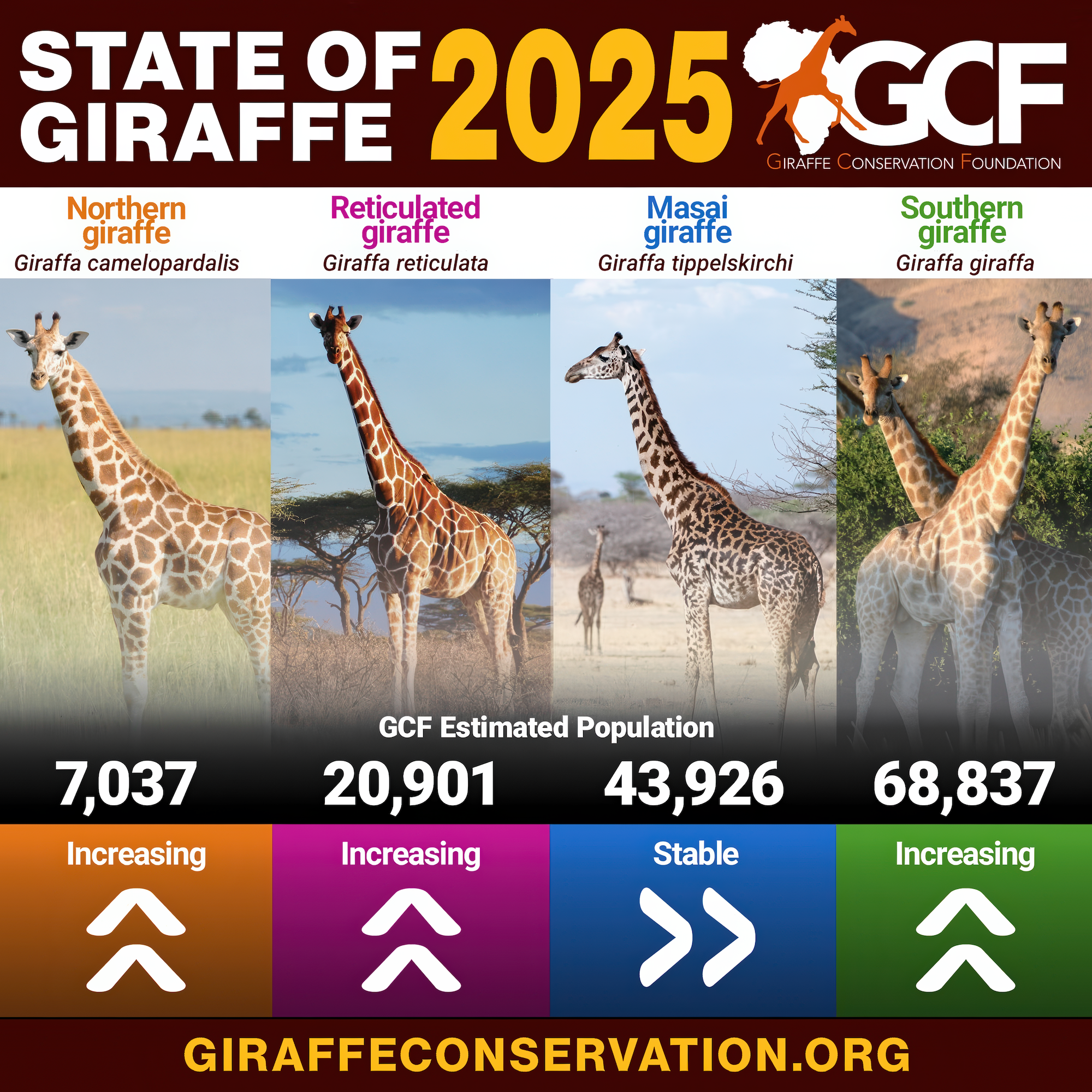

The IUCN decision coincided with the release of GCF's State of Giraffe 2025 report, which synthesised data from across the continent to provide the most accurate overview yet of giraffe numbers and distribution. Together, these two milestones represent a historic shift in our understanding of giraffe taxonomy, numbers, distribution, and conservation status.

The GCF State of Giraffe 2025 report is based on data compiled in their newly established Giraffe Africa Database (GAD), a platform designed to collate survey results and provide a consistent picture of each population’s status. Because survey methods vary widely in reliability, the report applies an Information Quality Index, assigning higher confidence to ground-based counts and individual monitoring, and adjusting aerial estimates upward to account for under-detection. This methodological rigour matters because past assessments often underestimated populations, or were based on rough guesses rather than systematic data. By combining hundreds of data sources, including government surveys, non-government reports, and peer-reviewed studies, GCF has created the clearest view yet of how all giraffe species and their populations are faring.

How are the four different species faring?

The overall picture is one of cautious optimism, with significant caveats. Across Africa, the combined numbers of all four giraffe species now total approximately 140,000 individuals. This is higher than estimates suggested over the last two decades, largely due to improved survey coverage, data sharing, and increased conservation efforts, but it still remains well below historical levels. In 1995, populations were far larger, and in several cases, they have fallen by more than half in just thirty years. When we consider the four distinct species separately, however, we discover a more complex and dynamic story.

The Masai giraffe, spread across Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Zambia, now numbers around 43,900 individuals. While their numbers have remained stable over the past five years, this species declined by nearly 40% during the previous three decades. The well-monitored Kenyan populations in the Amboseli, Tsavo, and Masai Mara ecosystems appear steady, and Rwanda's Akagera National Park has seen impressive growth from a small reintroduced herd. Tanzania, historically a stronghold, has remained poorly surveyed in recent years, creating a troubling data gap. The Luangwa subspecies of Masai giraffe comprises a small, isolated population of approximately 764 individuals in Zambia. Although this subspecies has increased by 18% over the past five years, it still remains far below historical estimates.

The status report for Northern giraffes paints a more sobering picture. Numbering 7,037 across Central, East, and West Africa, a 19% growth rate during the past five years masks a catastrophic 70% decline since the mid-1990s. The three subspecies tell the story in sharper detail. The Kordofan giraffe is now primarily concentrated in Chad, where it holds two-thirds of the population in Zakouma National Park. In contrast, Cameroon and the Central African Republic have experienced significant declines, with perhaps only a handful of individuals remaining in the latter. The Nubian giraffe subspecies has fared somewhat better, with nearly 4,000 individuals, many of which reside in Uganda's Murchison Falls National Park and Kenya's Ruma National Park; however, the population in South Sudan is in sharp decline. The West African giraffe, once numbering just 70 individuals in Niger, has recovered to a minimum of 669, but remains highly vulnerable due to its small range and the fragile political situation of the country.

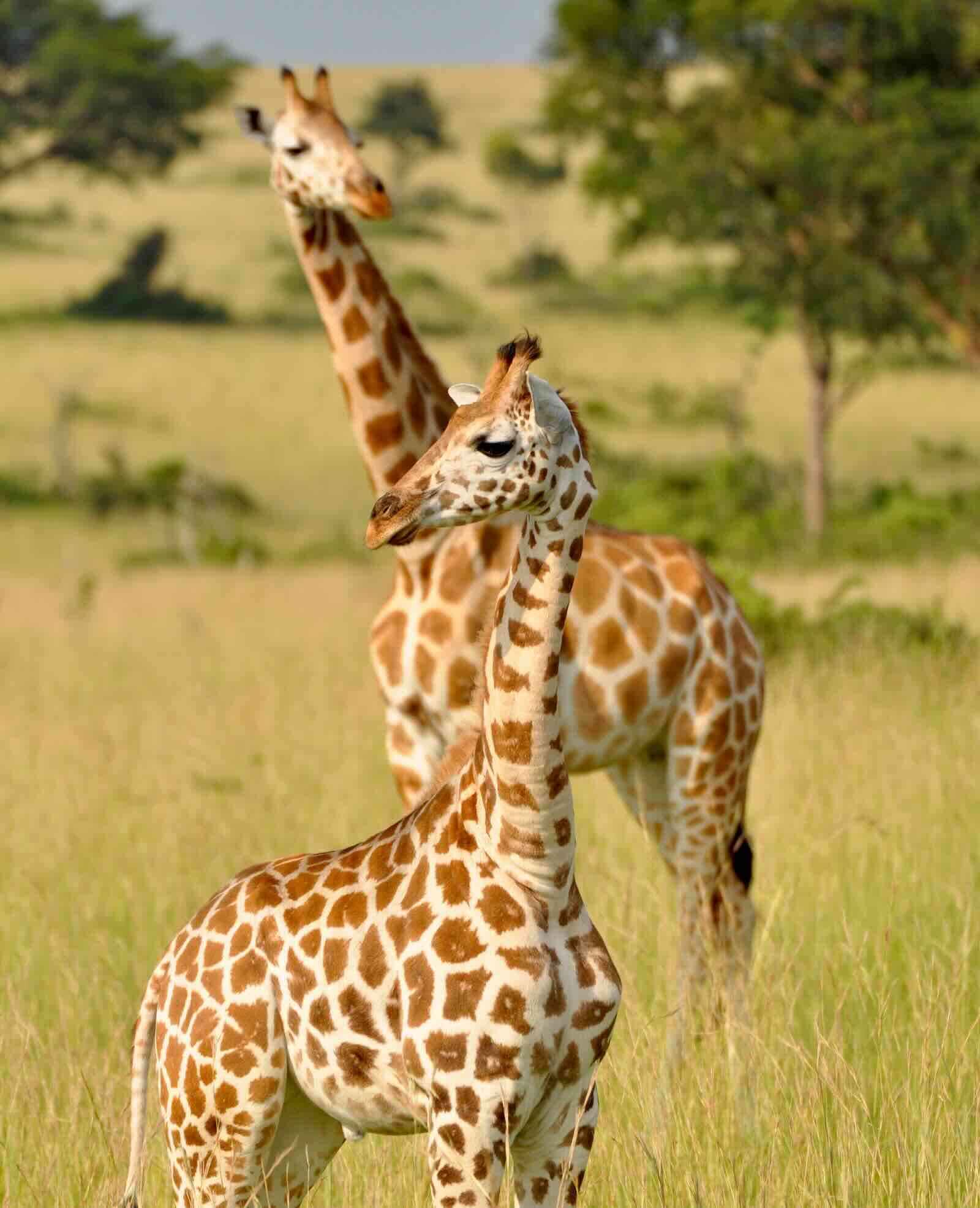

The Reticulated giraffe, instantly recognisable by its lattice-like coat pattern, now numbers about 20,900. Kenya holds almost the entire global population, with key strongholds in Garissa, Laikipia, Marsabit, Meru, Samburu and Wajir. Together, these areas account for 98% of their total. These populations are increasing, but Ethiopia and Somalia remain poorly surveyed, with perhaps only a few dozen surviving in these insecure regions. Overall, the population of Reticulated giraffes has increased by 31% since 2020, but remains 42% lower than the 1995 levels. Conducting more surveys in their remote areas would help gain a better understanding.

The Southern giraffe, by contrast, is a modern-day conservation success story. At nearly 69,000 individuals, it is the most numerous species and has more than doubled in size over the past three decades. Namibia alone holds nearly 14,000 of the Angolan subspecies, while South Africa hosts almost 30,000 of the South African subspecies. Botswana, Zambia, and Zimbabwe also maintain strong populations, and reintroductions into Malawi and Mozambique have been successful. The Southern giraffe demonstrates what is possible when robust national conservation frameworks, community engagement, and private landholders align to protect and expand populations.

Using our knowledge to guide giraffe conservation

While these species-level assessments provide clarity, it is essential to note that each species and its local populations often face very different circumstances. Some small, isolated populations are declining rapidly and could vanish within years without intervention. Others, especially where conservation translocations and management strategies are in place, are recovering. Countries that have developed National Giraffe Conservation Strategies and Action Plans – such as Chad, Kenya, Niger, and Uganda – have seen positive outcomes. Despite progress, challenges remain significant. Habitat loss and fragmentation resulting from the expansion of agriculture and infrastructure are reducing the giraffe's range across East Africa. Poaching continues in regions with weak governance, with giraffes hunted illegally for meat or traditional uses. Climate change is altering vegetation and water availability, adding further pressure to these ecosystems. In many areas, particularly in the Central African Republic, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Tanzania, data gaps hinder effective planning. Without sustained monitoring, conservationists cannot accurately track trends or respond to emerging threats.

This is why the IUCN's decision to recognise four giraffe species carries such weight. By treating them separately, the global community can direct conservation funding and policy toward the species most at risk. Preliminary findings suggest that three of the four species – the Masai, Northern, and Reticulated – are threatened, underscoring the urgency of targeted action. The Southern giraffe, though currently secure, still requires careful management to prevent future declines. Stephanie Fennessy, Executive Director of GCF, captured the stakes clearly: What a tragedy it would be to lose a species we've only just discovered.

As the leader in giraffe conservation throughout Africa, the Giraffe Conservation Foundation provided not only updated numbers with their State of Giraffe 2025 but also a model for how to build conservation around robust science. By integrating genetic discoveries, field surveys, and international collaboration, it sets the stage for a new era of giraffe conservation. 2025 will be remembered as the year when giraffes were finally seen not as one animal but as four – each with its own history, challenges, and prospects. It may also be remembered as the year when the world decided to stand tall for these gentle giants and initiated targeted efforts to ensure they will continue to roam Africa's landscapes for generations to come.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.