How long-term monitoring of Namibia's woodlands contributes to understanding African ecosystems

9th November 2025

9th November 2025

Across the grasslands and woodlands of Africa, a network of researchers is collecting long-term, highly detailed data on plants and their environments. This effort fills significant gaps in our understanding of how woodland savanna ecosystems function and respond to direct human impacts and climate change.

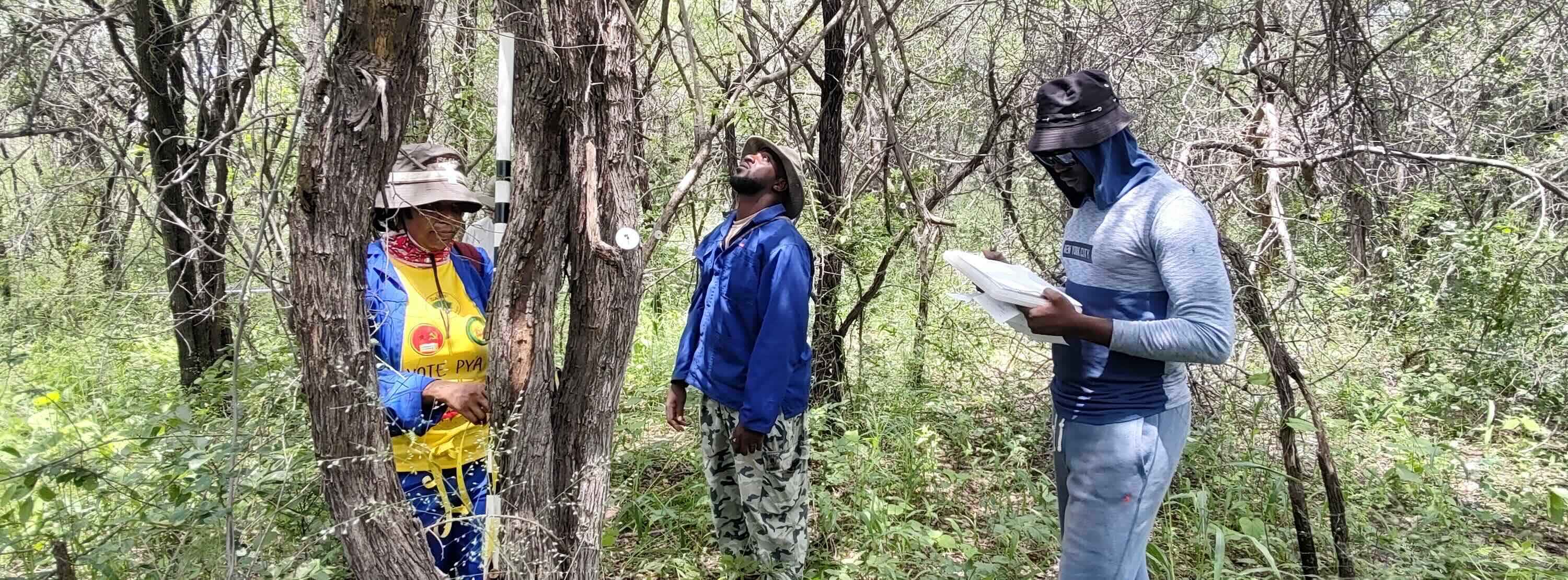

Professors and students at the Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST) Biodiversity Research Centre have joined colleagues from international universities in this new network. One of the main tools they are using to better understand woodlands is called a Permanent Sampling Plot (hereafter, ‘plot’), which is a one-hectare block of land that supports a representative sample of vegetation. After they are identified and marked, the researchers can return to these plots every few years to re-record detailed information on the plants within them. This data is used to monitor the species present, their size, and how these characteristics change over time.

Each plot is carefully selected to capture the diversity of the landscape, taking into account vegetation cover, species composition, elevation, soil type, and land-use history. While the plots must be accessible, we typically select areas that are unlikely to be disturbed by humans, allowing us to understand natural processes and apply these insights to other natural areas. We also explore how people interact with the land by establishing plots in areas grazed by cattle or adjacent to farmland. This work is always done in collaboration with landowners and local residents to ensure long-term access to these valuable sites.

The only indication that a piece of land is within one of our research plots is the presence of four permanent corner markers and the small metal tags fixed to the tree trunks. Each tag has a unique number, allowing us to track each tree over time. The plot corners serve as anchors from which we run 100-metre measuring tapes to define our plot borders each time we visit. These permanent markers must be unobtrusive yet sturdy enough to withstand the attention of inquisitive elephants and baboons.

In Namibia, we have marked 23 plots at four sites, with most of them established in 2023. Three plots established by NUST in 2006 were re-established. Two of our sites are located in State Forests (Kanovlei in Otjozondjupa and Hamoye in Kavango East), one is in a private protected area (Ongava Private Game Reserve in Kunene), and the fourth is situated within the Sachinga Livestock Centre in Zambezi. Each of these sites hosts woodlands that are dominated by different tree species, allowing us to compare these ecosystems.

The value of long-term, detailed studies on Namibian woodlands is multiplied when we add our data to the network of similar sites across southern Africa. Our plots are part of the Socio-Ecological Observatory for the Southern African Woodlands (SEOSAW), which was established to help researchers standardise their plot marking and research methods across the region.

As we conduct our studies in Namibia, our colleagues are doing similar studies on plots in other countries. When we combine our data and knowledge through SEOSAW, we can look for long-term, widespread trends and features of African woodlands that would go unnoticed if each study group focused solely on its own country. The overarching aim of SEOSAW is to understand how these dynamic ecosystems are changing and how this influences biodiversity, carbon storage, and local livelihoods.

What kinds of data do we collect when we visit our plots? This depends to some extent on which studies we are currently undertaking and the standard data collection protocol established for the long-term SEOSAW monitoring work. During most visits, we measure mature trees by recording stem diameters and noting signs of mortality or resprouting. We may also estimate the percentage cover and biomass of grasses, forbs (leafy plants that are not trees or shrubs), leaf litter, and woody debris. Each researcher in our team has their own projects that will either utilise these measurements or incorporate additional data to answer their respective research questions.

For Alice Jones, a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh, data from these long-term plots are the foundation of her doctoral research into savanna tree recruitment strategies. Using species composition data collected from the mature tree surveys, she investigates whether the trees we see today are successfully reproducing to maintain stable populations. During visits to the plots, she systematically samples the soil seed bank and seedling layers. By identifying and counting the species present in these early life stages, Alice can trace recruitment patterns and pinpoint potential bottlenecks in regeneration. Her work sheds light on the long-term stability of tree populations, which is vital for understanding the future of savanna ecosystems and guiding conservation efforts.

Leena Naftal, a PhD student at NUST, is using the tree measurements and information from soil cores to estimate the amount of carbon stored in both vegetation and soil. She will use this information to produce detailed carbon stock distribution maps for northern Namibia, parts of Angola, Zambia, and Botswana. These carbon stocks form the basis of potential carbon markets, whereby communities or local authorities are compensated for maintaining or restoring natural vegetation to capture carbon dioxide. Without this initial dataset, we cannot determine the amount of carbon our woodlands store, which is essential information for carbon markets and trading.

The detailed ground-level data from our plots complement data collected using satellites and other large-scale research. NASA’s Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) is an instrument installed on the International Space Station that produces 3D images of the Earth's surface using LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology. Another method, called Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS), produces even more detailed 3D models using earth-based lasers.

Hermane Diesse, a PhD student at NUST, combines information from GEDI and TLS with data from plots at three of our study sites and other sites in the SEOSAW network, extending beyond Namibia. He is investigating how rainfall and fire interact with forest structure, and how the canopy and subcanopy layers influence species diversity and plant biomass above the ground (i.e., excluding roots). His work shows that small trees and shrubs in dry woodlands contribute a greater proportion of the total above-ground biomass than those in wetter woodlands, which are dominated by larger trees. While wetter areas generally support higher overall levels of above-ground plant biomass, drier areas support a unique share of both biomass and diversity in their understorey components.

These results have significant implications for conservation strategies and carbon credit allocation. Many carbon assessments exclude trees and shrubs smaller than 5 cm or 10 cm in diameter, leading to the underestimation of both carbon storage and biodiversity value. Diesse's work highlights the importance of incorporating small trees and shrubs into carbon assessment protocols, particularly in dry woodlands. This would more accurately capture the carbon storage potential of these ecosystems and significantly increase their estimated contribution to climate mitigation.

Gabriel IK Uusiku, a Master's student at NUST, is investigating the relationship between seasonal leaf changes (known as phenology) and litter decomposition in semi-arid savannas. Using the plots at Ongava Game Reserve equipped with phenocameras (camera traps with the movement sensor disabled), he captures daily vegetation imagery to track seasonal canopy dynamics.

The dominant trees in this area include Mopane (Colophospermum mopane), Purple-pod Cluster-Leaf (Terminalia prunioides), and Blue-leaved Corkwood (Commiphora glaucescens), all of which lose their leaves in winter. The leaves then accumulate on the ground as leaf litter, thus returning nutrients to the soil. The link between leaf greenness (as determined by the cameras) and the amount of leaf litter that accumulates and decomposes on the ground provides insight into the functioning and resilience of savanna ecosystems.

The NUST team, led by Prof. Vera De Cauwer, has significantly enhanced the impact of their individual research projects by contributing to the SEOSAW network. Students from as far afield as the University of Edinburgh, or as close as our neighbouring countries, can tap into this valuable database to answer questions that no researcher could achieve alone. Each of the plots in Namibia is part of a much larger puzzle. While each piece is important, the state of southern Africa's woodlands is only revealed when we put the pieces together and view the whole picture from multiple research perspectives.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.