The Coronavirus and Namibian Conservation – How you can help

Namibian Chamber of Environment

1st June 2020

While most Namibians have been called to stay at home in “lockdown” during the last month, Namibian conservation is not in lockdown. Rangers, game guards, and anti-poaching units working for the government, communal and freehold conservancies, and on private farms are still hard at work. The government’s effort includes an important partnership between the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT), the Namibian Police Force (NAMPOL) and the Namibian Defence Force (NDF), which are supported by various non-governmental partners.

While us humans have had to stop what we are doing and make major changes to our lifestyles, nature has carried on doing what it has always done. Those who are tasked with monitoring, managing and protecting the natural world must therefore keep up their efforts. Their services are essential, and have been recognised as such by the government.

But these essential services are in great danger, especially those that have been funded largely through tourism until now. Photographic and hunting clients are the main source of income for our National Parks, conservancies, and private game ranches. Because most of these clients are from other countries, the tourism industry is an excellent source of foreign exchange during normal times, but it is also extremely vulnerable to global disruptions like the coronavirus pandemic. Indeed, tourism operators experienced a sharp downturn in their income long before Namibia took steps to limit the spread of the pandemic. Furthermore, it will take a long time after our lives have returned to “normal” before tourism will start to pick up again.

This will have an enormous impact on every sector of Namibia’s conservation efforts. A significant portion of the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism’s (MEFT) budget is derived from revenue generated from international photographic and hunting tourists. While National Parks like Etosha use the income from entrance fees paid by photographic tourists to manage the Park (including anti-poaching patrols), the Game Products Trust Fund channels revenue from hunting into critical species management and anti-poaching work across the country. Without these inputs from tourism, MEFT’s budget is likely to be severely diminished, especially considering the broader economic downturn in the wake of the pandemic.

Similarly, communal conservancies rely almost entirely on tourism of one form or another to generate their own cash income (about N$ 61 million in 2018) and many conservancy residents are employed in this sector (with salaries amounting to N$ 65 million in 2018) . The conservancies use their income to employ game guards, who are the backbone of the conservancy system and work at the frontline of community-based anti-poaching efforts. The massive blow suffered by tourism will likely result in many job losses among conservancy residents and severely hamper the conservancies’ ability to pay their game guards.

The many freehold landowners that manage game on their properties for tourism and/or hunting purposes are also in for a tough few years, to put it mildly. These private guesthouses, game ranches and reserves provide employment for many rural Namibians and contribute significantly to the national tourism industry. Many private game ranches host black rhinos as part of the hugely successful custodianship programme managed by MEFT. Like the Parks and conservancies, private game owners have invested in their own anti-poaching teams to protect rhinos and other species. Without sufficient income from tourism, they will have little choice but to reduce their employee numbers and their level of investment in anti-poaching.

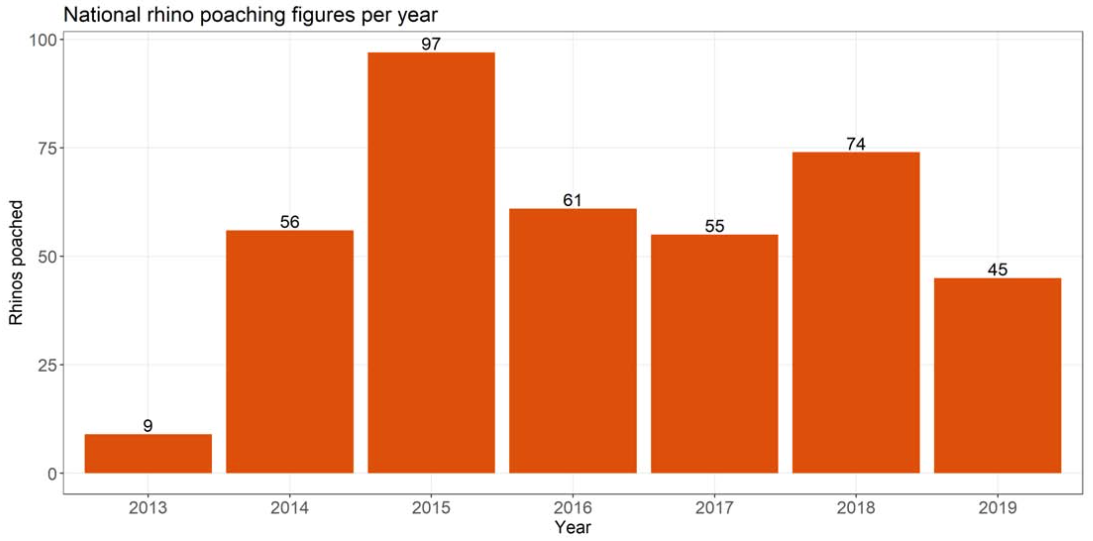

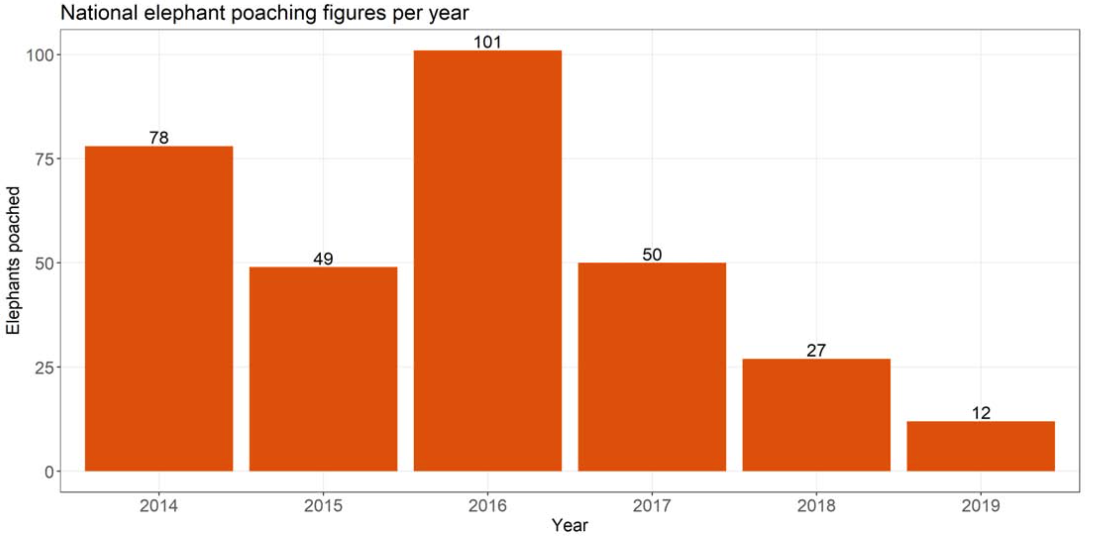

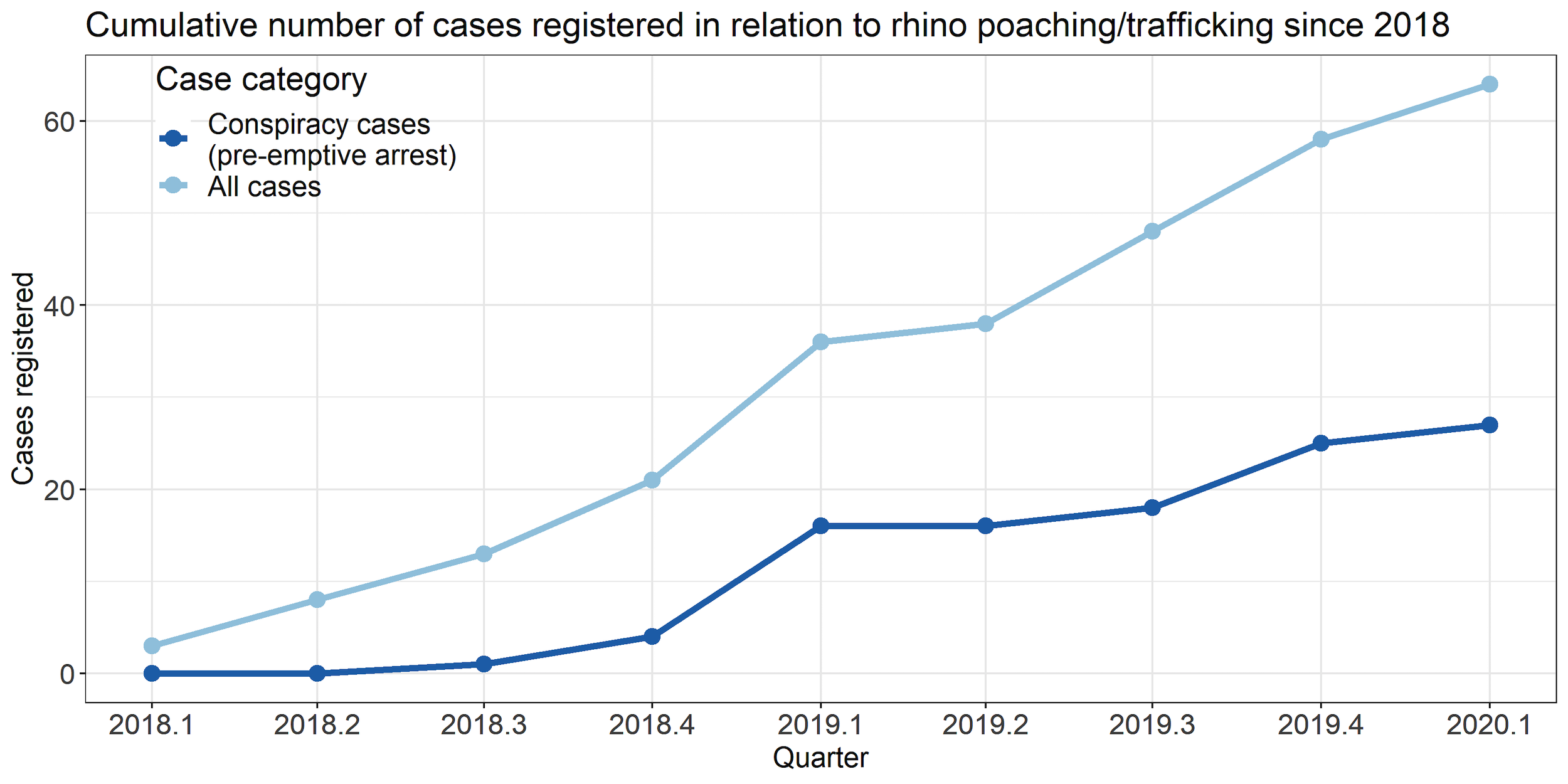

All three of the above conservation groups have been heavily involved in combatting wildlife crime in Namibia, and their efforts have borne much fruit thus far. The official wildlife crime report for 2019 reveals that rhino and elephant poaching have declined substantially over the last few years (Fig. 1 and 2). Pangolin poaching is a newer, increasing threat that is receiving ever more attention from Namibian law enforcement. Of particular note is that the number of rhino-related pre-emptive arrests has increased continuously from zero in the first half of 2018 to over 25 during the first quarter of 2020, arrests that have certainly saved many rhinos (Fig. 3).

The communal conservancies in the Kunene and Erongo Regions have proven especially effective in preventing rhino poaching; no rhinos were poached at all from August 2017 until March 2020. The recent case of two poached rhinos in Puros Conservancy shows that, despite the success thus far, anti-poaching efforts must continue. Indeed, even while most of us have stayed at home, MEFT rangers, conservancy game guards, Save the Rhino Trust rangers, and private anti-poaching teams have remained on high alert and continued their patrols.

There seems to have been a slight lull in wildlife crime during recent months, as anti-poaching teams and law enforcement officers have maintained their relentless pace regardless of the lockdown. Unfortunately, this may just be the calm before the storm. The economic downturn and widespread job losses will force more people into poverty and make joining the illegal wildlife trade that much more attractive, while poaching for subsistence may become a critical means of survival for some rural households. It is also possible that reduced tourist presence will embolden poachers who may feel that their activities will go unnoticed. At the same time, all of the dedicated conservation partners mentioned here will experience prolonged financial pressure and will have to stretch their resources to the very limits.

The coming years will prove a stern test of Namibian conservation. Thankfully, this field of work is full of passionate people who have often managed to accomplish excellent work despite shoestring budgets. But in the face of the coming storm, they need our help. With foreign income at an all-time low, these essential conservation workers need Namibian support.

In response to this growing threat, Honourable Minister Pohamba Shifeta launched the Conservation Relief, Recovery and Resilience Facility on the 4th of May 2020. This fund, currently worth N$16 million, was established by MEFT through funds raised by the Environmental Investment Fund, the Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organisations (NACSO), World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), and with pledges of support from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and Nedbank Namibia.

You too, can support anti-poaching efforts simply by visiting the Parks, conservancies, and private guest farms around the country as soon as movement and accommodation restrictions allow. Alternatively, you can donate directly to conservation in the communal conservancies through Save the Rhino Trust (for their rangers) or Tourism Supporting Conservation (TOSCO) that is also working with the above partners to support game guards and lion rangers in communal conservancies. Investing in one of B2Gold’s 1,000 Rhino Gold Bars that they have donated to conservation will provide direct financial support for community rhino rangers and rhino guards in all communal conservancies with rhinos in the Kunene and Erongo regions. Individuals and businesses will be able to support the National Parks directly through the recently announced “Friends of the Parks” programme once it becomes operational. The outbreak of coronavirus requires solidarity to see us through; our wildlife and their protectors need our support now more than ever.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.orgThe Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) is an umbrella Association that provides a forum and mouthpiece for the broader environment sector, that can lobby with government and other parties, that can raise funds for its members and that can represent the sector.

www.n-c-e.org

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

Gail C. Thomson is a carnivore conservationist who has worked in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana on human-carnivore conflict, community conservation and wildlife monitoring. She is interested in promoting clear public communication of science and conservation efforts in southern Africa.

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.