Fewer black rhinos have been poached in the Kunene Region's communal lands than in Etosha National Park or on privately-owned, fenced farms. This startling fact is cause for celebration and further investigation. I therefore interviewed the team from Save the Rhino Trust to find out more about this successful model for rhino conservation.

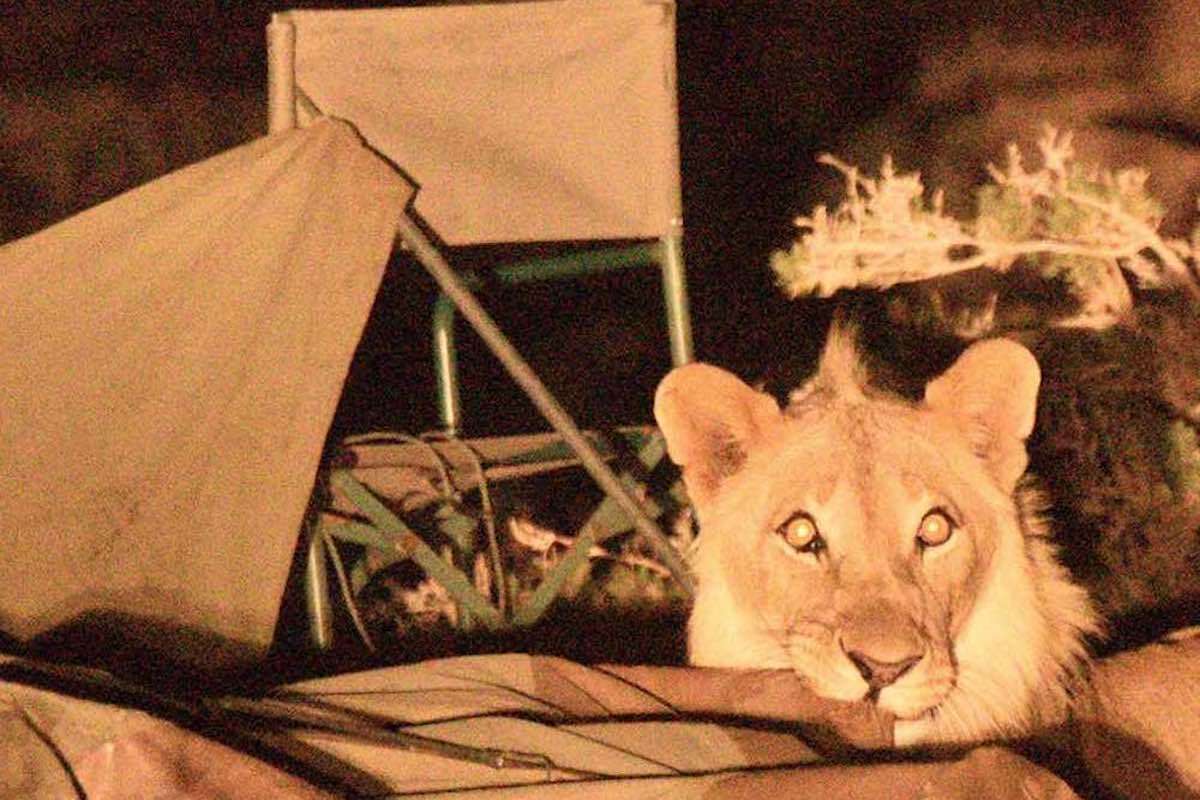

In a world of rampant poaching and wildlife trafficking, how do Namibia's black rhinos continue to roam freely and relatively safely on unfenced communal land? Some say that perhaps we don’t know the real numbers of rhino poached in this area, possibly because they don’t believe that conservation success of this kind is even possible. Yet these rhinos are individually identifiable and closely monitored—the low poaching rates are real, not imagined.

Perhaps rhinos are just easier to conserve in a desert environment where few people live? This answer is plausible, but does not account for the whole story, as rhinos were severely poached in Namibia's sparsely populated Kunene Region during the 70s and 80s. If that trend had continued without intervention, there would be no free-roaming rhinos in the Kunene today. Clearly, the arid environment and sparse population are not sufficient as explanations.

What, then, is the secret sauce for rhino conservation? And if we identify it, can we apply it to other areas or species threatened by poaching? The best people to answer these questions are those involved in Namibia's Conservancy Rhino Ranger Incentive Programme. This remarkable partnership spans government, communal conservancies, non-government organisations (NGOs) and universities who have come together to implement, monitor, evaluate and adapt their approach to rhino conservation over time.

Protecting rhinos during a poaching tidal wave

The Rhino Ranger Programme started in 2011 after a meeting convened by the Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) to respond to the impending wave of rhino poaching that had already hit South Africa. Namibia's rhinos seemed more vulnerable than ever, and some envisioned a bleak future of militarised anti-poaching teams keeping the few remaining rhinos under lock and key. The fate of the functionally extinct northern white rhino was already starting to look like the inevitable destiny of black and white rhinos in South Africa, and perhaps even Namibia.

Yet the meeting in 2011 at Wêreldsend (the headquarters of Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC) and a field base of Save the Rhino Trust (SRT)) proved to be the start of a different journey for rhinos in northwest Namibia. Besides MET and the NGOs (SRT, IRDNC and Namibia Nature Foundation), conservancy leaders attended the meeting to discuss how they would deal with the looming poaching threat.

Conservancies have been a key part of Namibia's conservation story since independence, but the idea of armed poachers infiltrating communities and offering large sums of money for information about rhinos seemed a daunting challenge. The discussions—often focused on increased law enforcement, fines and jail sentences for offenders—started sounding like a return to the ‘bad old days’ when local community members were treated with suspicion as either potential poachers or aiders and abettors of trafficking syndicates. The emphasis was laid on catching and punishing poachers.

Several conservation elders were present at those initial meetings who had seen this movie before, and were determined to prevent a remake. Garth Owen-Smith and Vitalus Flory (both since passed away) were among the voices that called for greater community involvement in rhino conservation, rather than focusing solely on government or NGO rangers. The team from SRT agreed with their sentiments: We knew from our strategic planning and performance reviews at the time that SRT and MET rangers alone would not be able to protect the rhinos from the kinds of armed criminal syndicates that were operating in South Africa,

recalls Simson !Uri-≠Khob, CEO of SRT. Vitalus’ passionate speech was exactly what we needed to get the conservancies fired up and inspired to join our rhino conservation efforts as active partners.

Training community rhino rangers and improving patrol efficiency

The resulting Programme was designed to harness the values and strengths of the conservancies, government and NGOs to protect black rhinos. This partnership was forged in fire. The newly minted Rhino Rangers (selected from the pool of conservancy game guards) were put through an intensive 12-month patrolling experience with SRT rangers in the field. While they were still gaining experience and refining patrol methods, rhino poaching increased from 1-2 per year to its peak of 18 rhinos killed in 2014.

Despite their hard work, some of the Namibian media accused the rangers of colluding with rhino poaching syndicates. After a thorough independent investigation, the SRT and conservancy rangers were vindicated. While the rangers were doing their level best, the team knew that their approach was not working as well as it could.

We started turning the tide on poaching after reflecting on how we were conducting our patrols,

says Dr Jeff Muntifering, SRT's science adviser, even though bringing community rhino rangers on board tripled our manpower, we were still patrolling the area in vehicles. When we switched from vehicle patrols to foot patrols, we started covering much more ground.

In this new system, one vehicle could drop off and pick up multiple foot patrol teams at different locations.

Once the team had started to use their burgeoning new rangers more effectively, they started seeing signs of success. Where previously a rhino may have been dead for months before a ranger found the carcass, now they were detecting carcasses within days. This is critical for poaching cases, as investigations are more likely to be successful when the trail is still warm. Each rhino in the region is individually identifiable based on SRT's ear notch system, and they found a significant increase in the number of times each rhino was sighted per month (their findings are summarised in this recent scientific paper).

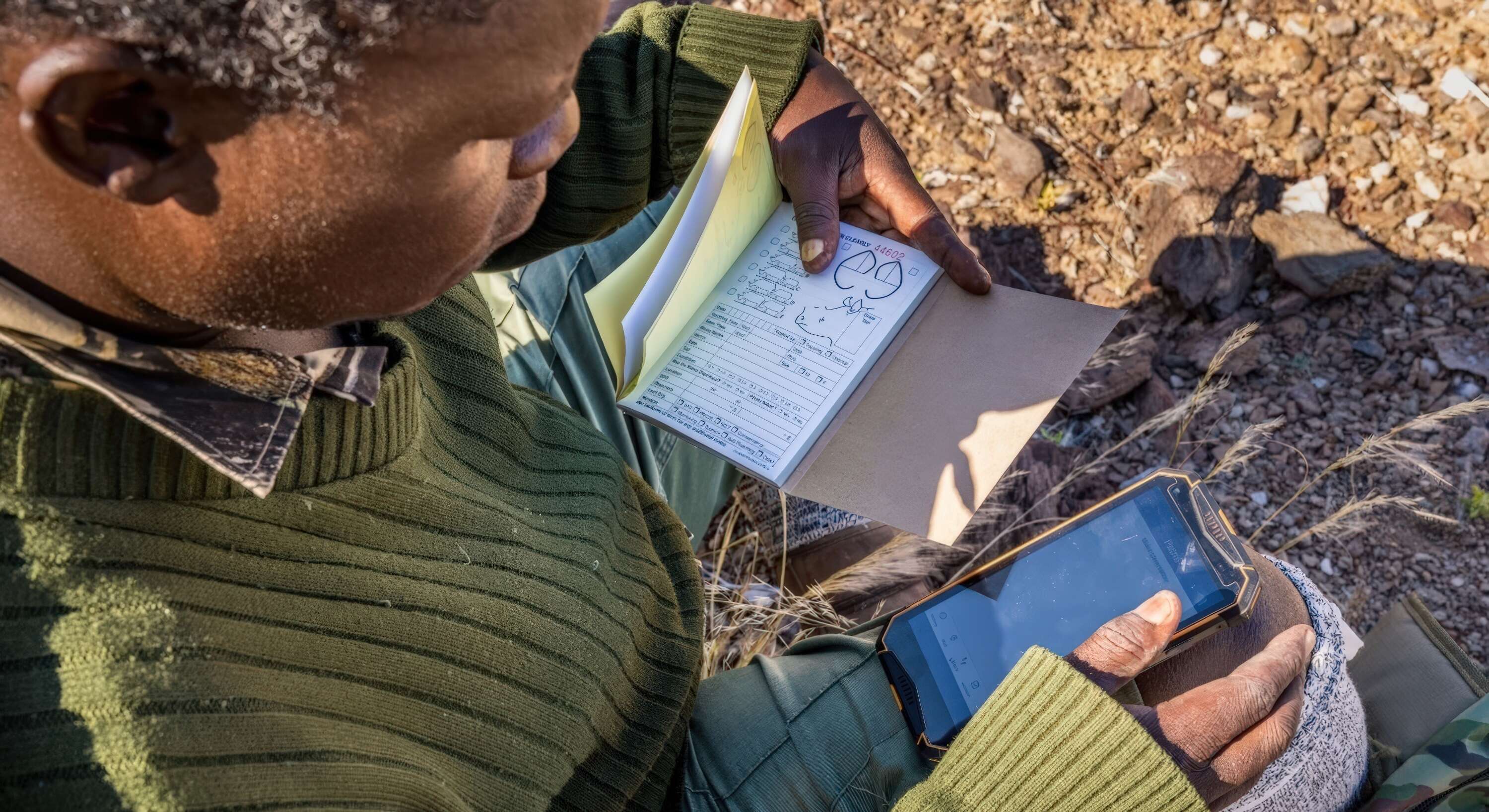

The programme's effectiveness was further enhanced by using the Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool (SMART) that allows rangers in the field to collect data on smartphones that link up with a central database. The information produced in SMART allowed the programme managers to find out which rhinos had not been seen for too long and dispatch ranger teams to look for them.

SMART is also used measure ranger performance in terms of the number of kilometres they patrol and rhinos they have sighted. This information was used to create healthy competition among the rangers for who could patrol the largest area and spot the most rhinos each month. The best rangers are recognised at annual Kunene Rhino Awards ceremonies each year, when their achievements are publicly celebrated. Unlike many other organisations involved in anti-poaching work, SRT never succumbed to routinely using lie-detector tests on their rangers, choosing to build on trust and incentives rather than suspicion and punishment.

Beyond rangers: reaching the wider community for rhinos

Although the Rhino Ranger Programme emphasises ‘boots on the ground’, they have not focused on patrol effort as myopically as many other anti-poaching efforts. The secret sauce of successful rhino conservation has one key ingredient that cannot be overlooked: generating wider community support and positive attitudes towards rhinos. Without supportive communities, even the most dedicated conservancy ranger would be hard-pressed to save rhinos.

Since the conservancy rangers were trained to track rhinos, eight tourism companies have signed nine contracts with conservancies to offer rhino tracking as an activity for their guests. Rhino tracking therefore boosts tourism in the region, which is a major source of employment for households in the Kunene Region.

The Rhino Pride campaign and associated community-focused activities is a critical element in the overall strategy to conserve rhinos in the Kunene Region. What started as an annual soccer and netball tournament to commemorate World Rhino Day has become a six-month league affiliated with the National Football Association. This initiative, known as the Rhino Cup Champions league and in partnership with Wild and Free Foundation (USA), has attracted many young people, with most of the Kunene conservancies fielding teams that are supported by wildlife-based income.

Pride in the Kunene Region reached an all-time high when the region's soccer team won the national Newspaper Cup for the first time ever with female coach 'Mammie' Kasaona—who is also the commissioner for the Rhino Cup Champions League in Namibia—leading their men's team to glory. Many of the young men in that team will remember the energetic rhino mascot parading around their local soccer fields as a visible expression of the link between rhinos and their sporting dreams.

While we continue to support soccer tournaments in schools and conservancies across the Kunene, we are now moving into children's literacy and alternative livelihoods,

says Lorna Dax of SRT. The Reading with Rhinos programme features a family of rhinos that 'reads along' with children in books donated to over a dozen schools in the region, with more to come.

In ≠Khoadi-//Hôas Conservancy, unemployed men and women are being taught to make rhinos and other animals from wire and beads to sell at lodges and to overseas markets. I am especially excited by the number of women who are participating in our art project, which is still in its pilot phase,

says Lorna who comes from this conservancy, because women are the beating heart of the family—when women prosper, everyone prospers.

The strategy behind the Rhino Pride campaign is more subtle than normal environmental education and awareness efforts. Rather than teaching people about rhinos or telling them why they should care about them, the Rhino Pride Campaign associates the species with improved livelihoods, enriched lives, fun, and literacy. In this way, rhinos are promoted as an integral part of life in the Kunene that would be sorely missed if they were poached to local extinction.

People: the key ingredient in Namibia's secret sauce

Figuring out which of the ingredients in this secret sauce is most important to rhino conservation would be challenging, as each component is mutually supportive. Considering the Kunene from the perspective of an international poaching syndicate shows how the overall strategy deters poaching. With so many people supporting rhino conservation, those trying to get information on rhinos or to recruit poachers are likely to be reported and caught before they even start poaching.

Instead of focusing on heavily armed law enforcement to catch poachers, our experience shows that supporting and aligning our initiatives with the values of local communities leads to the most effective, ethical, and affordable rhino protection,

says Jeff, When conservation programmes truly reflect what matters to the people living alongside rhinos, everyone benefits—and the animals are safer too.

The syndicates are also likely to find out that each rhino is so closely monitored by rangers that their poaching activities will be picked up quickly and reported to investigators in the Blue Rhino Task Team. These factors combine to make rhino poaching in the Kunene more challenging than poaching in areas with less widespread support for rhinos and fewer ranger teams on the ground.

The feared poaching tidal wave has turned out to be little more than a ripple in the communal lands that were considered to be especially vulnerable in 2011. Conservancy rhino rangers, SRT, and their partners did not crumble or admit defeat during the poaching spike in 2014, but instead found new ways of operating to increase patrol efficiency. Innovative operations and SMART technology are matched with the timeless principles that undergird community conservation in Namibia: building trust, responding to community needs, and using incentives rather than punishments to garner support.

Our principles and processes can be applied to other situations and threatened species,

says Simson, since conservation is about people, and people respond well when they feel like conservationists genuinely care about them.

Perhaps local people are the most important ingredient in our secret sauce—whether they are rhino rangers or soccer stars, men, women or children.

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.