Between cliffs and communities: The story of Kunene's highland elephants

13th November 2025

13th November 2025

When Captain James Shortridge wrote about Namibia in 1934, he observed that elephants were largely confined to the Caprivi and, quite unexpectedly, to the dry, rugged Kaokoveld in northwestern Namibia (now in the Zambezi and Kunene regions, respectively). Some elephants used the ephemeral springs on the southern edge of the Etosha Pan, but they were few in number.

Today, elephants are plentiful in the Zambezi and Kavango regions and Etosha National Park, while they persist in the northwestern Kunene Region. The elephants in the Kunene move across communal land, among villages and settlements, and also into freehold farmland, crossing and traversing farm fences. This population includes the famed ‘desert elephants’, who prefer the arid western parts of the dry Ugab, Huab, and Hoanib riverbeds. Occasionally, they have even wandered through the Skeleton Coast onto the beach. The ability of these elephants to adapt to these arid conditions has rightly earned them global recognition.

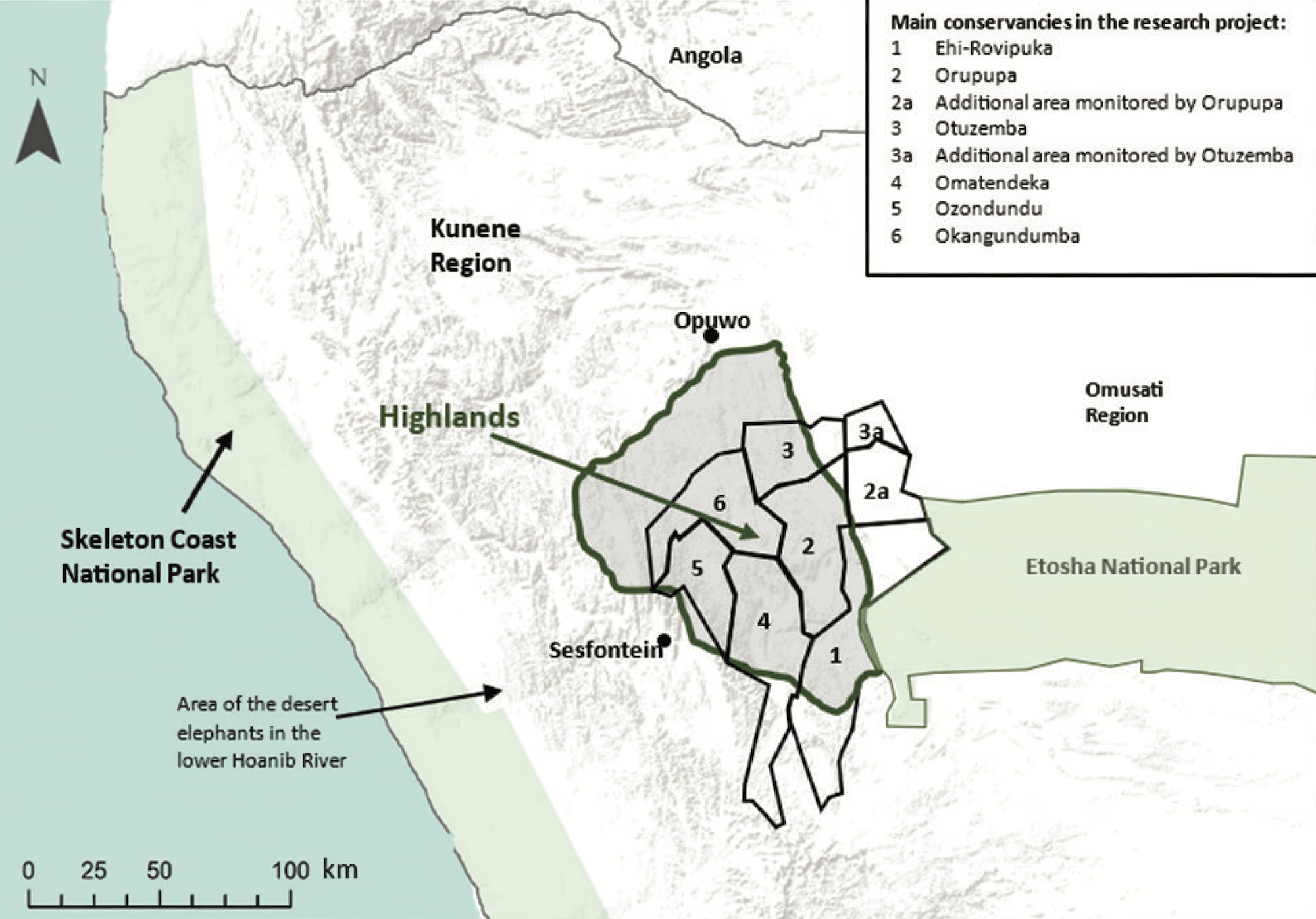

Between Etosha and the lower Hoanib River lies an area of highlands (see map), which is inhabited by a similarly unusual subpopulation of elephants. This area is roughly half the size of Etosha, with mountain peaks up to 1,800 metres. The landscape features steep, rocky slopes and some wide valleys, dominated by mopane trees. There is a growing population of elephants in these mountainous areas, thought to be numbering well over 100, depending on their movements in and out of the highlands area. The ability of these ‘highland elephants’ to scale high mountains makes them just as fascinating as their desert-dwelling cousins.

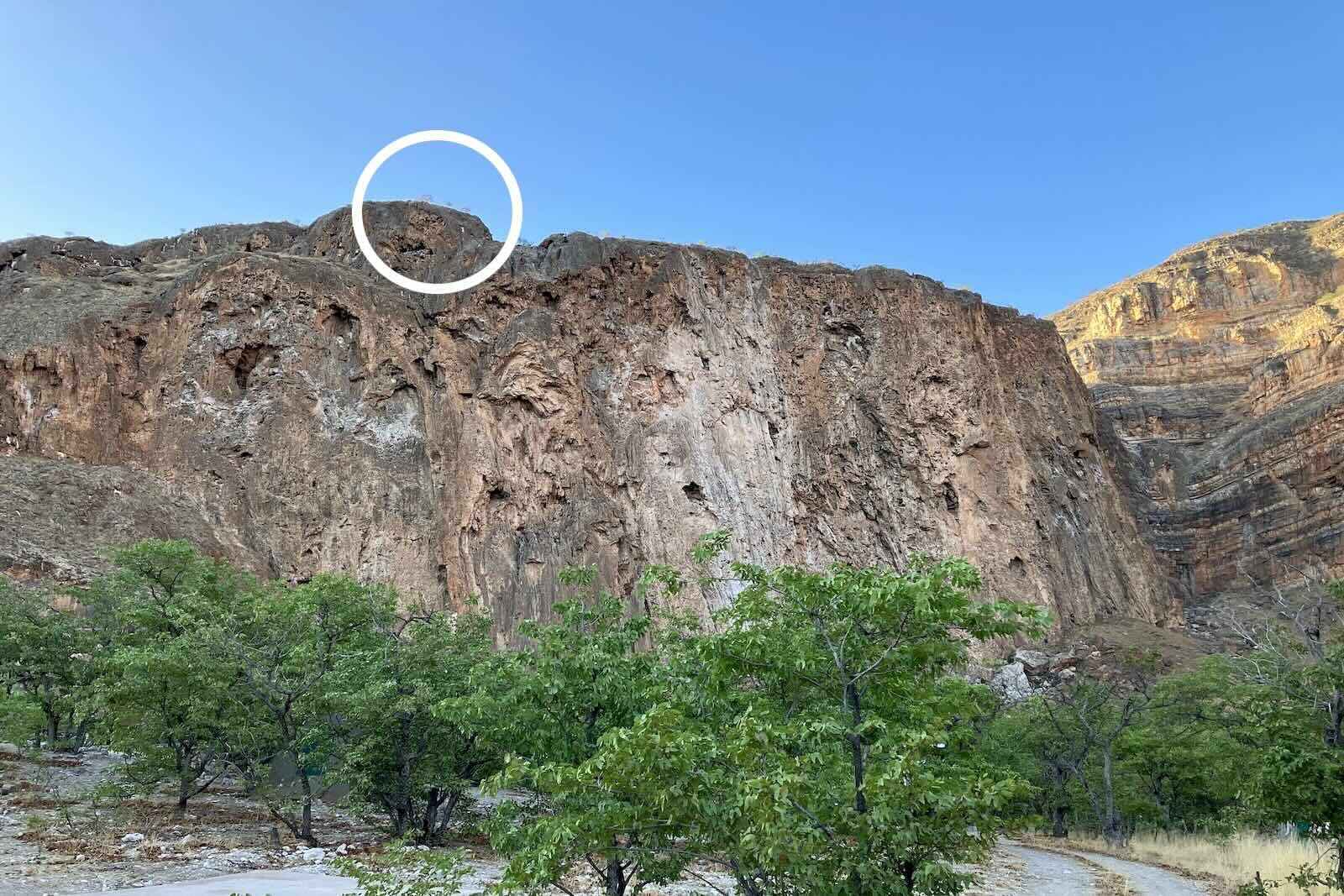

The relatively small number of highland elephants spread across a large area makes them difficult to observe, especially during the day. Often having to rely on water pumped for livestock near villages, the elephants tend to visit water holes at night when they can drink without being disturbed. Our team is excited each time we see elephants, but we are even more amazed by the elephant dung and browsed trees that indicate their ability to climb the steep, rocky hillsides we hike up during our research. We have two interlinked research projects that aim to gain a deeper understanding of these mountaineering pachyderms.

The first project started in 2021. Due to the difficulties in observing and tracking the elephants, the focus was on collating the knowledge of the community game guards who conserve the wildlife of these special highlands. The game guards are employed by communal conservancies and trained with support from Namibian conservation organisations. Some community game guards have over 20 years of experience in their roles, combined with a lifetime of living in these wild areas. Their roles include keeping records of incidents of human-elephant conflict, noting elephant sightings, and gathering evidence of elephant movements from their numerous foot patrols, including those in the highlands.

Our study employed semi-structured interviews with 34 game guards across six conservancies (see map), complemented by extensive field walks to ground-truth the common findings. This information enabled us to estimate the total elephant population in the highlands and gain a deeper understanding of elephant movements and behaviour, including which plant species the elephants prefer to eat.

The game guards confirmed that the elephant population in the area has been growing over the last 10-20 years, potentially due to the more reliable water supply. More boreholes have been drilled for people and livestock, and solar-powered pumps mean that water is always available. Almost all of the game guards frequently observed elephants walking up the steep mountain slopes to find their favourite trees, such as softwood trees in the Commiphora genus and the African star chestnut. The game guards’ information was confirmed through field walks to observe trees that have been browsed by elephants in the highlands, including high on cliff-tops.

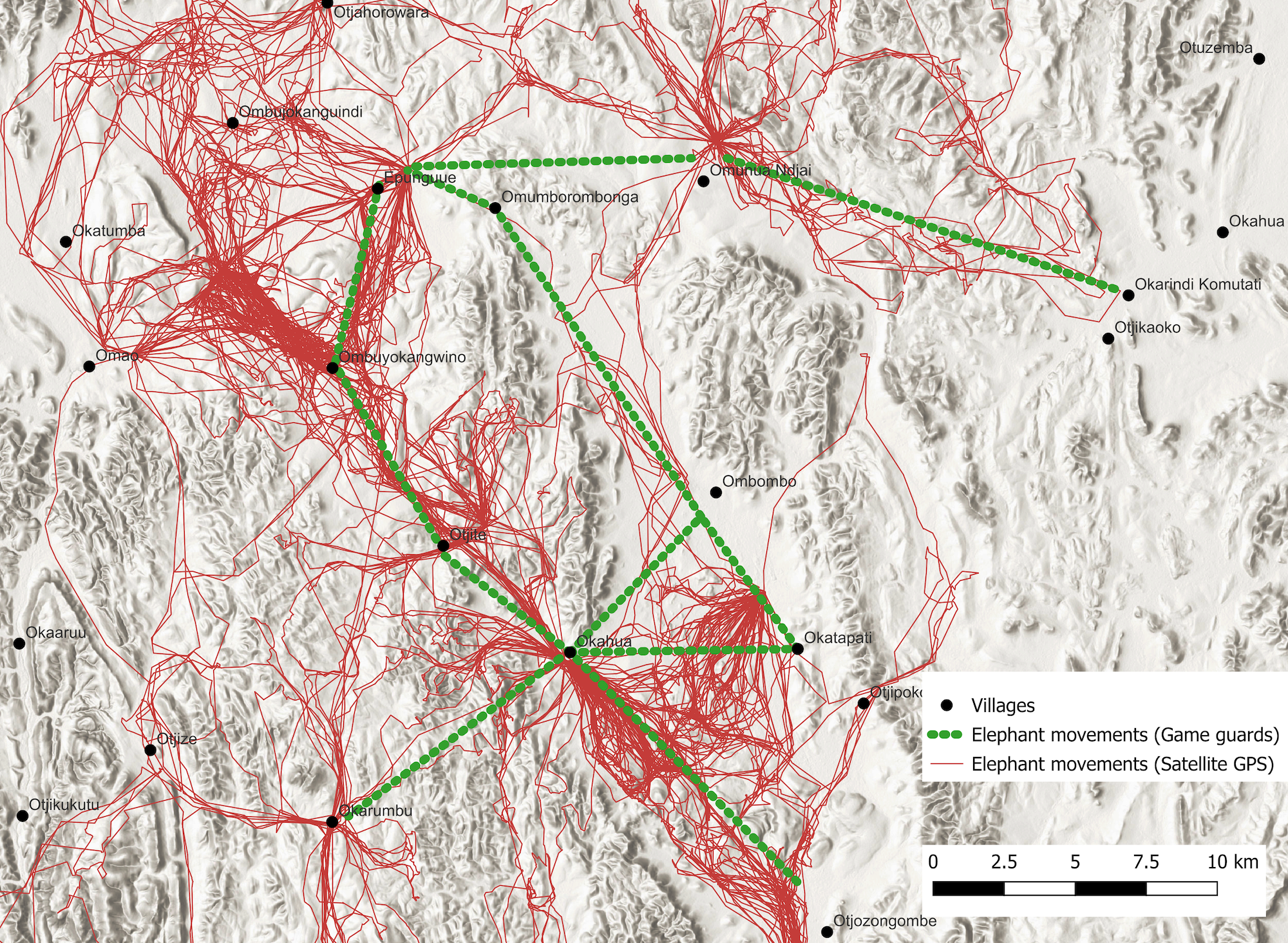

The work with game guards involved participatory mapping to capture their knowledge of routes taken by elephants and areas where elephants were not known to occur. This fitted well with the second research study, which used satellite tracking data from three of the highland elephant herds. The matriarchs of these herds were collared as part of a larger study of elephant movements across the entire Kunene Region, designed to provide early warnings to farmers and villages when elephants are nearby.

It is interesting to see how local knowledge, combined with satellite technology, can provide such an accurate picture of elephant movements in these inaccessible areas. There are several cases where the movements of collared elephants align with the main elephant corridors identified by game guards (see map below). For example, the valley from Okarindi Komutati to the Omunua Ndjai cattle post in Okangundumba Conservancy was noted by game guards as a common elephant route, which was confirmed by satellite data.

On their way from one feeding area to another, elephants cross through villages, drink at troughs with livestock, and amble tranquilly through herds of goats and cattle. Understanding the movement pathways is crucial for conserving elephants and mitigating human-elephant conflict. Planning settlements or crop fields to avoid these movement areas will reduce conflict, while conservation efforts can focus on keeping and enhancing this landscape connectivity.

These highland elephants seem to be uniquely adapted mountaineers, just as the desert elephants have adapted to extreme climate conditions and little food and water. In the highlands, elephants favour specific plants only found on the slopes and tops of the mountains. This initial research opens an exciting door to a better understanding of the nimble and secretive elephants of the Kunene Highlands.

We have many questions to guide our future research. Are they specially adapted? What threatens their existence? How will climate change, increased human activity, and water availability shape their ecology? Do they sometimes move out of the highlands to connect with the desert elephants in the west, as well as with the Etosha elephants in the east? Are the increasing numbers a concern to the special tree species they feed on? Are there ways to avoid conflict with crop and vegetable farmers? And will their range expand northwards to the mountains near the Kunene River?

This research was made possible through funding from Michael Wenborn, the Oppenheimer Generations Fellowship in People and Wildlife, and the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism.

About the Author

Morgan Hauptfleisch is Director of Research at the Namibia Nature Foundation, Oppenheimer Generations Research Fellow in People and Wildlife, Extraordinary Professor at North-West University, and Adjunct Professor at the Namibia University of Science and Technology. Michael Wenborn is an independent researcher and PhD candidate at Oxford Brookes University.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.