Agriculture and wildlife conservation are often seen as conflicting sectors, particularly when wild animals damage crops or kill livestock, while tourism operations and associated conservation areas take up land that could be or were previously used for agriculture. In Namibia, the government has to perform a delicate balancing act between food security supported by farming on the one hand and securing the rich flora and fauna that attracts safari and hunting tourists on the other.

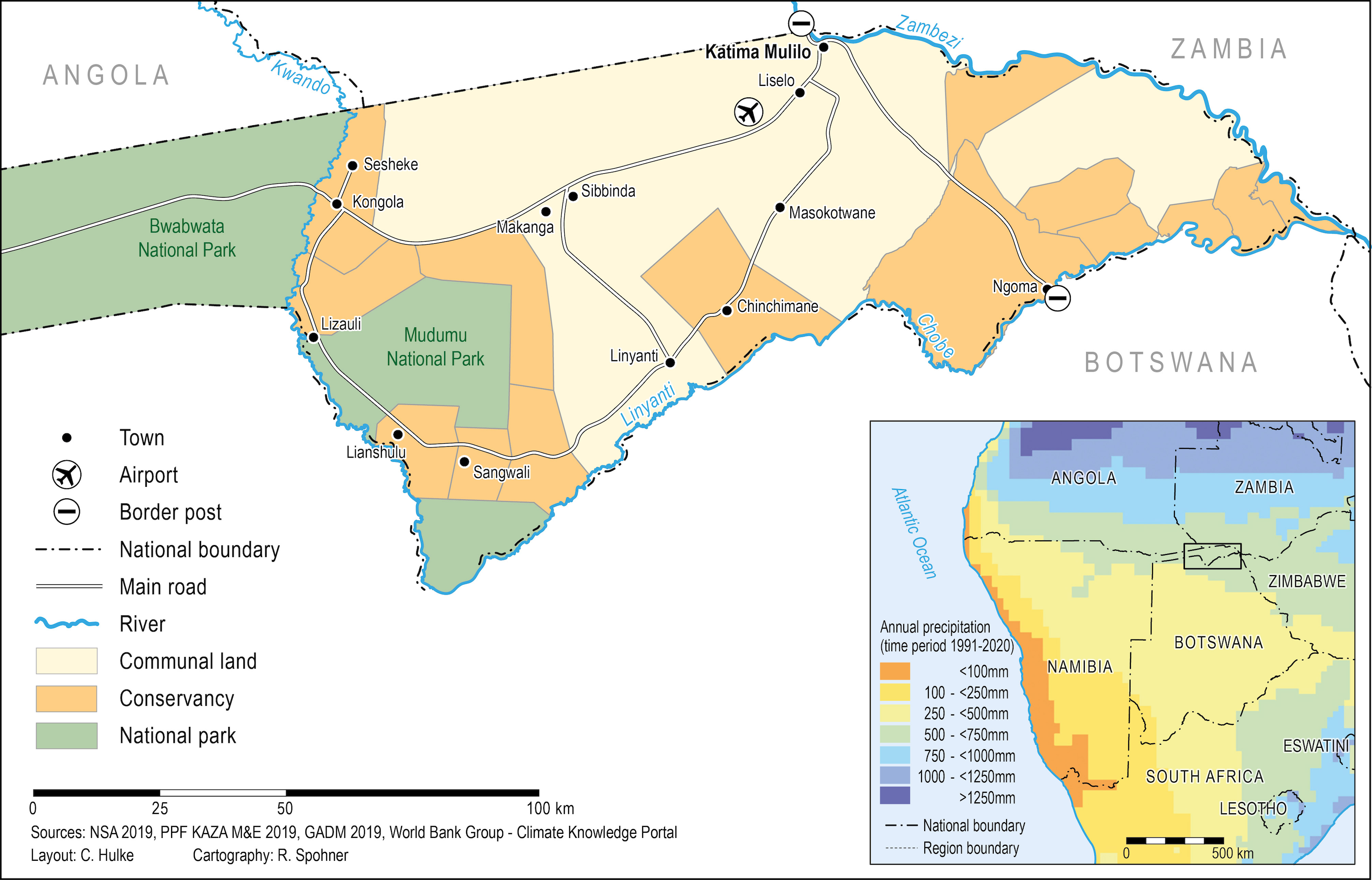

The Zambezi Region in north-eastern Namibia is a prime example of the need for balance between the agriculture and conservation sectors. As part of the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA), the region supports diverse wildlife, making it a popular tourist destination. Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) is a crucial element of economic development in the region that allows local communities to establish . The primary purpose of conservancies is to manage and conserve wildlife and use income generated from wildlife-based industries to support their members or undertake development projects. The region's economy and the livelihoods of its residents are thus significantly shaped by the impact of conservation initiatives.

On the surface, it would appear that wildlife should take precedence over agriculture, since tourism is one of the biggest sectors of the regional economy, whilst agriculture is characterised by low production subsistence farming, mostly involving family gardens and small-scale rain fed agriculture. But the story is more complicated than that since these developments raise questions on inclusivity, marginalisation and wellbeing of rural residents.

Communal conservancies in the region generate roughly 98% of their revenues from wildlife-based industries. However, research on conservancies shows that income from tourism does not reach all households equally, while agricultural production supports the vast majority of households in terms of food security and cash income from surplus sales. Apart from the growing importance of farming for subsistence, an organised regional value chain has emerged on the local level that links small-scale farmers to informal and formal markets and thereby provides a stable source of income and food supply at the same time. Clearly, both wildlife conservation and agriculture need support in a planned, integrated way that minimises conflict between the sectors and maximises benefits for rural households.

Researching links between conservation and agriculture

Building bridges between agriculture and conservation has the potential to produce ecologically sustainable and socially inclusive outcomes, if key players in these sectors work together. On the ground, the two are already deeply intertwined: On the wildlife conservation side, there are 15 communal conservancies in the Zambezi Region with over 33,000 members as of 2021. On the agricultural side, almost all conservancy members are farmers, and since conservancies were established to provide benefits to their members, integrating these sectors should start with conservancies. Consequently, following huge success in restoring wildlife populations, the CBNRM model is now challenged to restructure its processes towards integrative rural development, investing in value chain infrastructure to support sectors beyond tourism (such as agriculture), and supporting local initiatives and entrepreneurs beyond tourism/nature conservation.

To understand how these bridges can be built better, this project has focussed specifically on the role and agency of farmers to operate within conservation areas, their challenges but also potentials for collaboration. My work is part of a broader collaborative research project between the University of Cologne, Germany and the University of Namibia (UNAM) from 2018 to 2021. We studied ways in which small farms and nature-based tourism can combine to drive inclusive regional development in the Zambezi Region.

Besides rain-fed crops such as maize and mahangu, farmers recently started engaging in the production and marketing of fruits and vegetables. These horticulture producers in the Zambezi region are almost exclusively smallholders. By working collectively in farmers groups and local associations, farmers have recently established a local value chain for fresh vegetables and fruits. A highly dynamic, innovative and active farmers association called Zambezi Horticulture Producers Association (ZAHOPA) has managed to upgrade agricultural activities in the region and have a positive effect on farmers' livelihoods, even within conservancies.

In addition to grassroots developments, policies regulating the domestic market, such as a Market Share Promotion that requires importers of fresh produce to source a minimum percentage of this produce locally enables producers of the informal market to enter a local value chain. These top-down policies thereby strengthen local farmers and informal supply channels.

To take advantage of this enabling policy environment, local farmers still needed coordination, planning, and access to inputs. ZAHOPA has taken on this role, reducing local competition and helping farmers support each other. There is potential for further growth by delivering vegetables to lodges, which present a new market that is closer to farming areas, thus reducing transport costs and creating more direct communication links between the producers and their customers. However, this value chain is still in the process of consolidating into formalised supply channels. The midstream segment (e.g. transport, packaging, processing, and storage) lacks the infrastructure that is needed to link producers to markets more effectively as many farmers are operating in very remote areas within conservancies.

How COVID-19 created opportunities for cross-sector collaboration

Namibian conservancies were heavily affected by the immediate and long-term effects on the economy caused by border closures and the subsequent reduction of international tourism. In my research, I looked at the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on links between tourism and horticulture development in the Zambezi Region as part of the larger research programme on this subject.

During the pandemic, conservancies adjusted their benefit sharing system and restructured their activities towards agricultural value chains due to the decline of tourism income. They also reviewed their dependence on tourism and recognised the need for regional diversification and orientation towards agriculture. While tourism businesses shut down, farming remained stable and many people used farming and sales of surplus produce as a safety net. This has caused a stronger acknowledgement of horticulture in conservancies for food security and income generation for their members.

Conservancies thus realised their significant potential to support small-scale horticulture farmers. First, conservancy zonation plans influence land use and has until now benefitted nature conservation and tourism businesses by relocating farmers away from rivers and thus access to water for irrigation using pumps or buckets. Second, conservancies can use their revenues towards investing in projects that support farmers in addition to the human-wildlife-conflict self-reliance scheme that only offsets the actual losses experienced by farmers. To enable farmers to produce for formal markets, conservancies can invest for instance in boreholes, community gardens, transport for fresh produce, and building agricultural processing facilities. These ideas were developed only in the aftermath of the pandemic, which exposed the dependency and vulnerability of conservancies based on external income (mainly from tourism). These emerging linkages between the conservation and agriculture sectors must be strengthened to reduce the negative impacts of wildlife conservation on farming, such as human-wildlife conflict.

Whether these new endeavours will be successful, however, will depend on communication and coordination between higher-level institutions such as ministries and lobby associations in the tourism and agriculture sectors. The relevant government ministries need to create policies that enable local actors to adapt to multiple crises and pave the way for resilient forms of development.

Besides the COVID-19 pandemic, the Zambezi region in Namibia faces multiple challenges and an uncertain future, including the current energy and food crises and climate change impacts. However, my study revealed that conservancies are of immense importance to increase community resilience to shocks against future crises and uncertainties.

First, conservancies have opened up new avenues for economic diversification through wildlife-based tourism and related income-generating activities. Second, they empower local grassroots initiatives by involving community members in decision-making processes. This participatory approach fosters a sense of ownership and strengthens social cohesion. Third, conservancies promote adaptive capacity by facilitating knowledge exchange, skill development, and the adoption of innovative practices not only in tourism but also in related economic activities. These roles are besides the most widely recognised value of conservancies associated with capturing value from external investors or donors for the benefit of local communities.

Putting research into practice

In the final phase of my research project, small-scale farmers and conservancy staff and board members were brought together to discuss the findings of this research and chart the way forwards for CBNRM and farming. The workshops in five conservancies were jointly organised by the University of Cologne and ZAHOPA, with support from the University of Namibia, Katima Mulilo Campus. They took the opportunity to discuss some of the constraints experienced by local farmers and how conservancies could help address these.

In particular, participants noted that conservancies could invest in agricultural projects that improve the link between producers and consumers for a functional value chain, thus benefiting conservancy members engaged in farming. Conservancies could also facilitate information exchange between local producers and lodges located within conservancies, which a first step towards opening this potentially lucrative market.

The objectives and mandates of conservancies primarily relate to the conservation of natural resources. Consequently, conservancies have traditionally focused on limiting the environmental impacts of the expansion of agricultural land in favour of nature conservation, which created tension between these institutions and farmers associations. However, the Covid-19 pandemic has shifted this relationship towards cooperation and communication – a meaningful first step towards more integrated development that brings conservation and agriculture together.

The workshop discussions produced three main recommendations for conservancies and the broader range of stakeholders working and investing in the region:

- Strengthen grassroots initiatives: encouraging local initiatives and innovations through collective action, such as ZAHOPA, can be instrumental in developing and implementing regional standards and processing industries on a regional scale that meets the needs of local farmers.

- Contextualised development strategies: building on local resources, capabilities, and cultural heritage can be more effective than relying solely on national-level strategies. Tailored, place-specific interventions can strengthen existing value chains and identify emerging sectors with growth potential.

- Strengthen collaboration: fostering collaboration and knowledge exchange among diverse actors – e.g. private businesses, research institutions, local communities, and government institutions – can drive innovation and help overcome the challenges faced in rural areas like the Zambezi.

To conclude, studies on agricultural activities within conservancies in the Zambezi Region provide valuable insights into the role of local initiatives such as conservancy managers, members and associations in building regional resilience. Through sustainable resource management, economic diversification, and community empowerment, conservancies contribute to the overall wellbeing of communities and their ability to withstand and adapt to challenges and shocks. Strengthening the links between small-scale farmers and conservancies will benefit the CBNRM programme both in the Zambezi and other parts of Namibia. Building bridges between sectors will increase ownership of wildlife and its associated benefits, improve perceptions of nature conservation, and contribute to poverty reduction and food security.

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

Disclaimer

This blog post is summarising scientific articles published in recent years within the Collaborative Research Centre 228: Future Rural Africa. The research was conducted in close collaboration with researchers from UNAM, Katima Mulilo campus as well as the regional horticulture association ZAHOPA. Our partners have been crucial for data collection, analysis and interpretation. Views are my own. More detailed information can be found in the following articles. Please contact me for further comments, questions and discussions:

carolin.hulke [at] uni-koeln.de or c.hulke [at] lse.ac.uk

References

Hulke, C.; Kalvelage, L.; Kairu, J.; Revilla Diez, J.; P. Rutina (2022): Navigating through the storm: conservancies as local institutions for regional resilience in Zambezi, Namibia, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, online first. https://academic.oup.com/cjres/article/15/2/305/6554430

Hulke, C.; Revilla Diez, J. (2022): Understanding regional value chain evolution in peripheral areas through governance interactions – An institutional layering approach. Applied Geography 139. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S014362282200011X

Breul, M.; Hulke, C.; Kalvelage, L. (2021): Path Formation and Reformation: Studying the Variegated Consequences of Path Creation for Regional Development. Economic Geography, S. 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.1922277

Hulke, Carolin; Kairu, Jim Kariuki; Diez, Javier Revilla (2020): Development visions, livelihood realities – how conservation shapes agricultural value chains in the Zambezi region, Namibia. Development Southern Africa, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2020.1838260

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.