Against the backdrop of the global biodiversity crisis, Namibia has managed to secure large populations of African animals that survived the unrestricted hunting and destructive farming practices of colonial times. This included unregulated trade in wildlife parts to satisfy the growing demand in the major cities of America, Europe and East Asia for products such as ivory, ostrich feathers, carnivore skins, hippo skin and rhino horn starting in the late 19th Century.

The trend of declining wildlife populations continued under South African rule from 1915 to 1990, albeit for different reasons. In Namibia, the economy was primarily dependent on the production of meat and wool from large farms in central Namibia, and mining from the 1950s onwards. Many farmers viewed wildlife as vermin that competed with their livestock, leading to a systematic reduction of wildlife populations throughout the country.

Since the late 1960s and especially after the Nature Conservation Ordinance of 1975 when farmers were allowed to use wildlife on their properties, trophy hunting on privately owned farms increased. Farmers started to view wildlife as an additional or even alternative source of income to livestock and many cattle farms were converted into game farms. This stimulated a turnaround in wildlife numbers in central Namibia.

With the introduction of the Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) programme in 1996, the independent government aimed to support previously disadvantaged communities in communal areas by granting them rights to use wildlife, similar to the privileges previously enjoyed exclusively by white farm owners. The challenge facing independent Namibia now is balancing human aspirations for economic growth with the needs of increasing wildlife populations.

The Namibian CBNRM programme aims to achieve three main objectives: wildlife conservation, rural empowerment and regional development for people living in communal lands. Poverty remains a significant challenge in these remote rural areas, which were largely cut off from the economic growth in central Namibia during apartheid. By creating space for entire ecosystems to thrive against all odds, Namibia's contribution to global biodiversity conservation is invaluable.

Following government guidelines, communities can establish conservancies, which are local institutions that are largely self-funding and are tasked with the management of wildlife and distribution of resulting benefits. More than 90% of Namibian conservancies' self-generated income comes from benefit-sharing agreements with photographic (safari) or hunting tourism companies, often in combination. However, there is also considerable funding from international and national NGOs and donors, as well as significant support from the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism, mostly in the form of management consultancy, legal assistance, accounting and other forms of labour.

Keeping all of our eggs in the tourism basket is a fragile strategy, however. The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the risks of depending on global travel for conservation funding. The increasing pressure to ban hunting trophy imports into European countries from Africa and elsewhere is another looming risk for the business model of conservancies in Namibia.

In light of these external risks to tourism income, how can the CBNRM programme deliver on its promise of regional development? This question has been one of the focal areas of my research on the tourism value chain and community conservation in the Zambezi region since 2018.

The current status: tourism is important, but not enough to close the income gap

Since the end of apartheid, the number of tourism companies in the Zambezi region has increased dramatically. From four in 1990, the number of companies reached 24 in 2005 and 47 in 2018. This is reflected by the visitor numbers, which doubled from 30,000 in 2005 to 60,000 in 2018. Pioneering entrepreneurs with tourism industry networks, skills and investment capital have built a thriving tourism destination that attracts nature-loving visitors from around the world who come for recreation, hunting, fishing or photography.

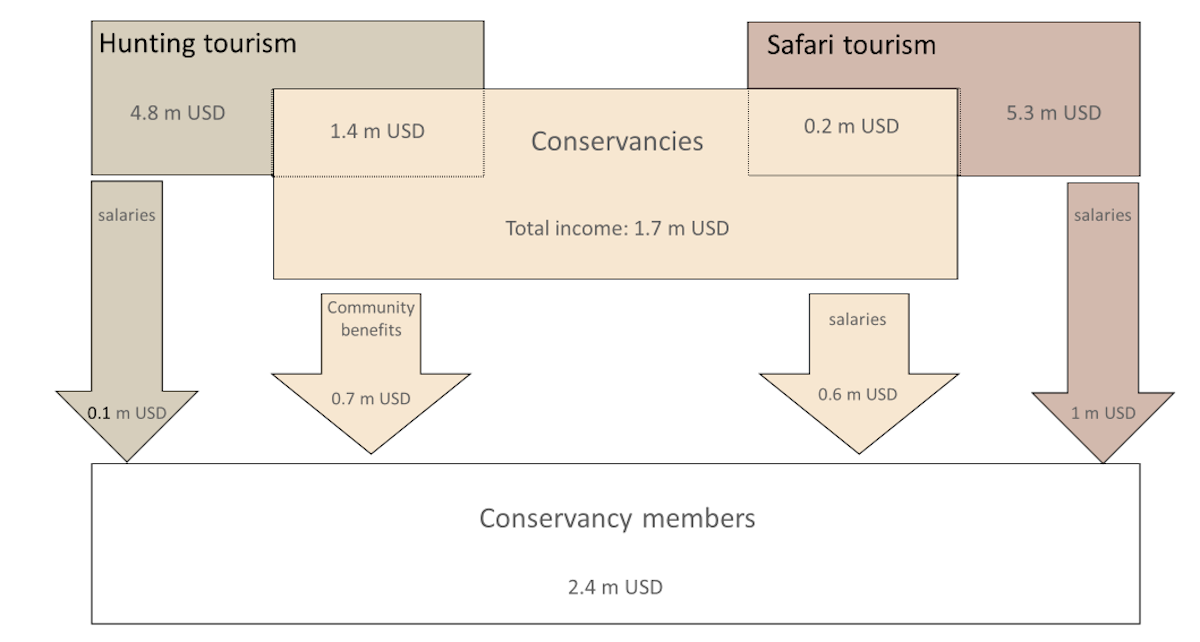

Safari and hunting tourism complement each other in generating income for the conservancies. For example, in the 15 conservancies in the Zambezi region, hunting tourism generated US$4.8 million in 2017, while safari tourism generated US$5.3 million. While safari tourism is concentrated in attractive locations, mostly along the river, hunting tourism can generate money from less attractive and less accessible areas.

In addition to corporate taxes, tourism operators contribute to conservancy funding. In the year 2017, hunting operators in the Zambezi region paid US$ 1.4 million to conservancies. Benefit-sharing agreements with safari lodges have contributed far less to conservancies (US$ 200,000). However, lodges create more jobs than hunting camps, with US$ 1 million paid in salaries by lodge owners compared to US$ 100,000 by the hunting operators. These jobs significantly increase household incomes. When conservancy staff salaries and community benefits such as funeral assistance, development projects and scholarships are included, conservancy members are able to retain approximately 20% of the gross revenue generated by hunting and safari tourism.

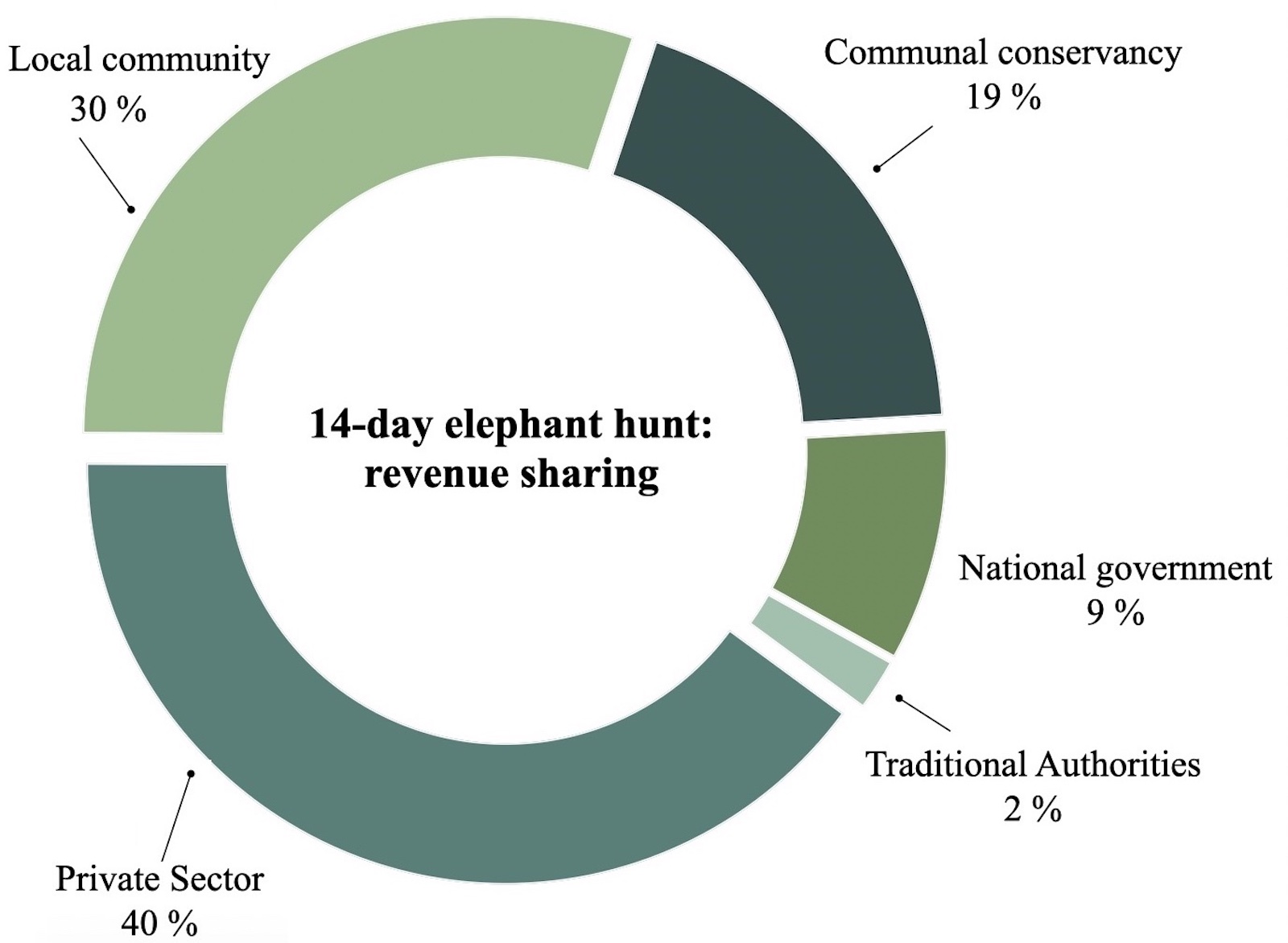

Overall, the proportion of income retained at the local level is significant. However, much of this money is used to fund the operation of the conservancy as an institution, leaving smaller amounts to benefit all community members. For example, on a 14-day elephant hunt costing approximately US$25,000, 19% of the total price goes to the community conservancies to cover operating costs, 9% goes to the national government through taxation and 2% goes to traditional authorities. Conservancy members receive 30% of the hunting package in the form of conservancy salaries, community benefits, hunting staff salaries and human-wildlife conflict offset payments. While 30% goes to community members, 40% is retained by the private sector, but this is not a net profit - lodges and hunting operators still have to cover necessary costs such as vehicle maintenance, logistics, sales and promotion, among others.

However, it is important to note that only a limited number of members really benefit. The communities are not as homogeneous as they might appear. Those employed in the lodges, hunting camps and conservancy generate direct income. Others, however, bear the costs of wildlife damage to their livestock or crops, while compensation schemes do not work well and development projects are often poorly managed.

Leakage is a well-known problem in tourism: it describes the phenomenon that destinations around the world are left with negative impacts, while large corporations keep the lion's share. For example, in cruise ship tourism most of the money is spent on board, leaving few dollars in the destinations. The same is true of other industries, such as mining or large-scale agriculture: in many cases, local communities bear the negative impacts but receive few or no benefits. In the chocolate value chain for instance, farmers in Ghana retain only 7.5 % of the overall revenue.

Limitations of tourism to drive rural development

In general, the CBNRM approach is not intended to replace or compete with agricultural activities, but rather to add value and provide complementary income opportunities. However, CBNRM comes with the promise of improving people's livelihoods. Many policy documents emphasise that wildlife conservation will improve the lives of people in conservancies. Although there are other drivers, the prospect of access to tourism dollars is one of the main incentives for communities to engage in wildlife conservation.

After several years of CBNRM, however, there is widespread dissatisfaction among conservancy members, based on the perception that conservancies are not distributing revenues adequately or equitably, and that compensation payments are often delayed. While some people have access to conservation structures, many conservancy members are not able to participate sufficiently to benefit from conservation revenues.

My data substantiate these perceptions. A household survey conducted in 2019 found that only 4% of the total labour force in the Zambezi region is employed in tourism or conservation, and that tourism contributes only 6% of household income in the region. If we look just at households in conservancies, the figure is higher, with 12% of household income coming from tourism. This income makes a difference to the households that receive it, and has a positive knock on effect to the local economy. But is it enough to meet the needs of a growing population hoping to close the income gap with the upper classes elsewhere in the country?

Tourism has three major limitations as a regional development strategy: First, while tourism generates significant income for protected areas, it may not significantly improve the livelihoods of the wider population. Second, Covid-19 has shown that it is too risky to have a mono-structured regional economy based solely on tourism. Third, tourism does not benefit all community members equally – it benefits those who find employment in lodges and hunting camps, but comes with costs to agriculture and livestock herding, which are practised by most community members. Wildlife crop raids have a negative impact on yields, and the most attractive land for lodges in the Zambezi Region is often along the rivers – where there is significant potential for agricultural productivity.

The legacy of apartheid-era injustices, inequalities and discriminatory laws weighs heavily on Namibia. The CBNRM programme has succeeded in creating the legal framework to return ownership of natural resources to local communities, but it is still lagging behind the regional development aspirations of many members. In the next blog in this series, I will present three ways to improve the development outcomes of the CBNRM programme: intensifying value creation from wildlife, creating an enabling business environment, and building resilient institutions. To ensure that nature has a place in a growing economy, I argue that a more holistic approach is needed. Three decades after independence, it is time to lift the weight of history.

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

This blog post is a summary of a number of scientific articles published in recent years within the framework of the Collaborative Research Centre 228: Future Rural Africa (crc-trr228.de). Scientific collaboration with researchers from UNAM has been crucial for data collection, analysis and interpretation. Views are my own. Please refer to the original articles below for more detailed information:

Kalvelage, L. (2023): Chapter 13 - Hunting for Development: Global production networks and the commodification of wildlife in Namibia. In: Ed: Currey, J.: Conservation, Markets, And The Environment In Southern And Eastern Africa Commodifying The 'Wild', edited by J. Currey. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jj.3643592.19

Kalvelage, L.; Revilla Diez, J.: Bollig, M. (2023): Valuing Nature in Global Production Networks: Hunting Tourism and the Weight of History in Zambezi, Namibia Annals of the American Association of Geographers, online first. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/24694452.2023.2200468

Vehrs, H.; Kalvelage, L.; R. Nghitevelekwa (2022): The Power of Dissonance: Inconsistent Relations Between Travelling Ideas And Local Realities in Community Conservation in Namibia's Zambezi Region Conservation and Society, online first. The-Power-of-Dissonance.pdf

Hulke, C.; Kalvelage, L.; Kairu, J.; Revilla Diez, J.; P. Rutina (2022): Navigating through the storm: conservancies as local institutions for regional resilience in Zambezi, Namibia. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, online first. Navigating-through-the-storm.pdf

Kalvelage, L.; Revilla Diez, J.: Bollig, M. (2021): Do tar roads bring tourism? Growth corridor policy and tourism development in the Zambezi region, Namibia. European Journal of Development Research, 1-22. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41287-021-00402-3

Kalvelage, L.; Revilla Diez, J.; Bollig, M. (2020): How much remains? Local value capture from tourism in Zambezi, Namibia. Tourism Geographies, 1-22. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14616688.2020.1786154

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.