Investigating human-wildlife conflict beyond conservancies

25th January 2023

The relationship between humans and wildlife in Namibia has been studied extensively, but most of this effort has focused on communal conservancies. While a few studies have examined the topic of human-wildlife conflict on commercial freehold land, there has been almost no research effort on resettled freehold farms and communal lands outside conservancies. Yet wildlife certainly roams on lands next to conservancies and national parks. The needs and views of the people living there cannot be ignored, especially when the wildlife includes elephants, lions and other nationally protected species.

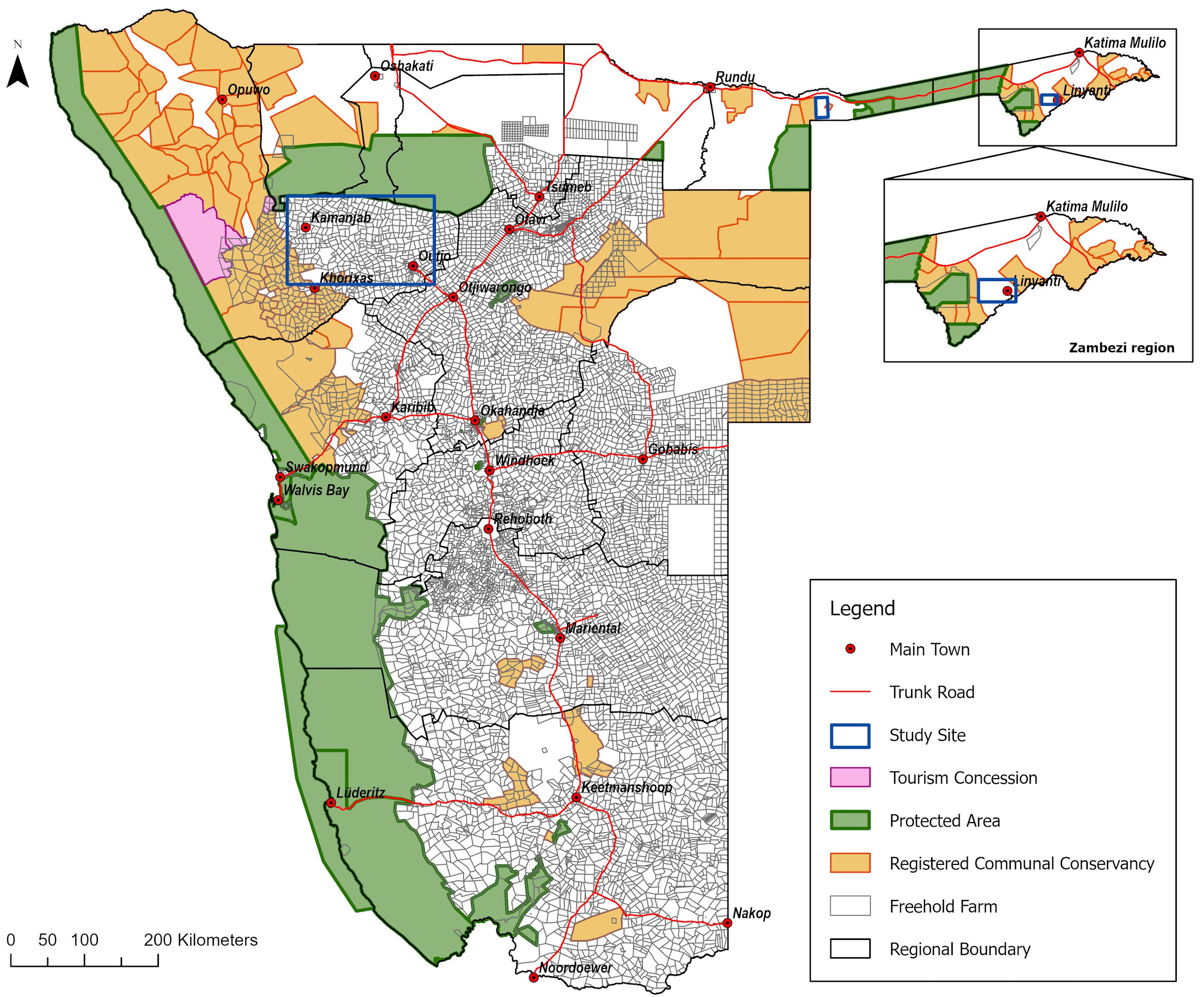

As part of my master's project funded by the Namibian Chamber of Environment, I investigated human-wildlife conflict on commercial, resettled and communal lands next to conservancies and national parks in the Kunene, Kavango East and Zambezi Regions. The communal lands I surveyed in Kavango East and Zambezi were located next to communal conservancies and not far from Bwabwata National Park and Mudumu National Park, respectively. The commercial and resettled farms surveyed in the Kunene Region were located close to Etosha National Park.

A commercial farm is a property on freehold land where the farmer holds the title deed for the whole property (usually a few thousand hectares) and farms on a commercial basis with livestock and/or wildlife. A resettled farm is a freehold property that was purchased by the government in order to settle people from previously disadvantaged backgrounds on land that they could farm; most resettled families will farm on a subsistence basis on an allotted portion of the freehold farm. Freehold properties of both kinds are usually fenced on their external borders and internally to form camps or demarcate resettled plots. People living on communal land have customary rights to occupy the area and farm there (usually for subsistence purposes), which is regulated by traditional authorities and regional land boards. By law, communal lands may not be fenced to create large farms like freehold properties, although each family may fence a small area near the homestead. These differences are important to bear in mind when considering the differences in how these farmers live with and view wildlife.

I started collecting data in September 2019 using a detailed questionnaire to find out more about how farming was done in these areas, what wildlife species caused what kind of damage, and what the farmers thought about wildlife in general. Having been born and brought up in northern Namibia myself before coming to Windhoek for tertiary education where I studied natural resource management and nature conservation, I am very much acquainted with the rural way of life especially the subsistence farming aspect. Despite the area where I come from being within a communal conservancy (Uukolonkadhi Conservancy) I have never experienced human-wildlife conflict first hand (other than weaver birds picking our Mahangu) since our area is far from where wildlife roams. I however became very well acquainted with this topic through my work at the Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organisations (NACSO). I was therefore happy to take the opportunity to research this topic for my M.Sc. Because my work at NACSO concentrated on communal famers within communal conservancies, I was not sure what answers to expect from people living outside communal conservancies, so I kept an open mind when asking questions.

The data confirmed that most farmers rely on crops (Kavango East and Zambezi) or livestock farming (Kunene) for their income or subsistence, with only four of the 142 I interviewed saying that they had off-farm employment. Some of the commercial farmers were venturing into tourism and game farming or ran mixed livestock and wildlife enterprises. The commercial and resettled farmers in the Kunene Region farmed mainly with livestock, so it was unsurprising that they reported predators as causing most of their problems, with spotted hyaena being the main predator of cattle (accounting for 70% of the losses) and black-backed jackal causing 55% of the small stock losses. Respondents from Zambezi and Kavango East that rely on crops more than livestock reported that elephants were their biggest problem (48% of damages), followed by antelope species (24%).

While much is said about human-wildlife conflict, it is important to look at losses to wildlife in relation to other losses. In the arid Kunene Region, drought caused more livestock losses than predation. In the Kavango East, disease was the biggest cause of livestock loss. Only cattle in the Zambezi Region were lost more often to predators than to other causes. Human-wildlife conflict was nonetheless prevalent across all regions, as 64% of the 142 farmers reported some losses or damages over the last year period.

Elephants in the Kunene Region were the main cause of infrastructure damages, which were reported as a frequent problem by commercial farmers and less frequently by resettled farmers. Elephants most frequently damaged fences, water points and pipes. This in turn affects livestock farming that uses this infrastructure. For example, one commercial farmer reported losing 60 cattle after elephants broke through his border fence. Infrastructure damage was not as common as livestock losses or crop damage in my sample, but particular incidents could be more costly than other losses.

Overall, communal farmers in the Kavango East experienced more conflict with wildlife than the other farmers in my study. Most of the respondents, regardless of region or land type, said that they believed that human-wildlife conflict was increasing in their areas. Commercial and communal farmers reported more losses and showed more concern about increasing conflict than resettlement farmers, the latter experiencing fewer losses overall than the other farmers.

I found that the commercial farmers had more tangible benefits from wildlife, particularly those that hunted for meat, or used trophy hunting or tourism to generate income. Because the communal farmers in my study live outside conservancies, they cannot legally generate income from wildlife. Nonetheless, most farmers placed some intangible value on wildlife such as the educational value of children seeing wildlife (42%) or the enjoyment experienced from watching wildlife (41%). Five of the 30 commercial farmers considered ownership of wildlife to be a benefit, but neither communal nor resettled farmers listed this factor.

The level of conflict that farmers report compared with the benefits they associate with wildlife combine to influence their views towards wild animals. 97% of the commercial farmers, 87% of the resettled farmers and 50% of the communal farmers did not want to see wildlife disappear from the land. However, a few farmers noted that their enjoyment of wildlife in general was different to their attitude towards predators and elephants that cause livestock losses or crop damages. For damage-causing species, they wanted some tangible benefits to offset the costs of living with them.

The study showed that human-wildlife conflict is prevalent on lands that fall outside communal conservancies and protected areas. The Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT) has recognised that farmers in these areas do not benefit from wildlife and do not have access to the conflict mitigation measures that are available within conservancies. The recent elephant auction that took place in the same area as my survey in the Kunene Region was meant to assist with infrastructure damages in this area. However, much more needs to be done.

Based on the data and my observations, human-wildlife conflict affects all types of farmers, and depending on their economic status and the frequency of the incidents, the impacts on their livelihood can be minimal to severe. We need to begin collecting information on conflict incidents in a systematic way – i.e. a national database on human-wildlife conflict outside communal conservancies – for management purposes in these areas. Either MEFT or Namibian universities could collect this information to help us understand exactly what is happening on the ground.

Researchers and conservationists need to establish relationships with these farmers and communities to jointly solve these challenges through coexistence and co-adaptive management. One of the ways researchers can work with farmers is to establish long-term studies and to monitor species that are known to cause problems. Farmers' attitudes toward wildlife may be changed through the awareness that such studies can create. These studies and relationships could also explore economic opportunities related to wildlife that causes conflict, which will be beneficial to the farmers and the animal species occurring in these areas.

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.