Law enforcement alone will not end wildlife crime

25th October 2024

25th October 2024

Independent Namibia has an excellent conservation track record, based on a sound legislative framework and pragmatic sustainable-use approaches. This has enabled healthy populations of most of the historically occurring wildlife in areas of suitable habitat. Namibia's elephant population is at its highest in more than a century. The country is home to the largest population of black rhinos in the world, and the second-largest population of white rhinos. Wildlife is one of Namibia's most valuable natural resources.

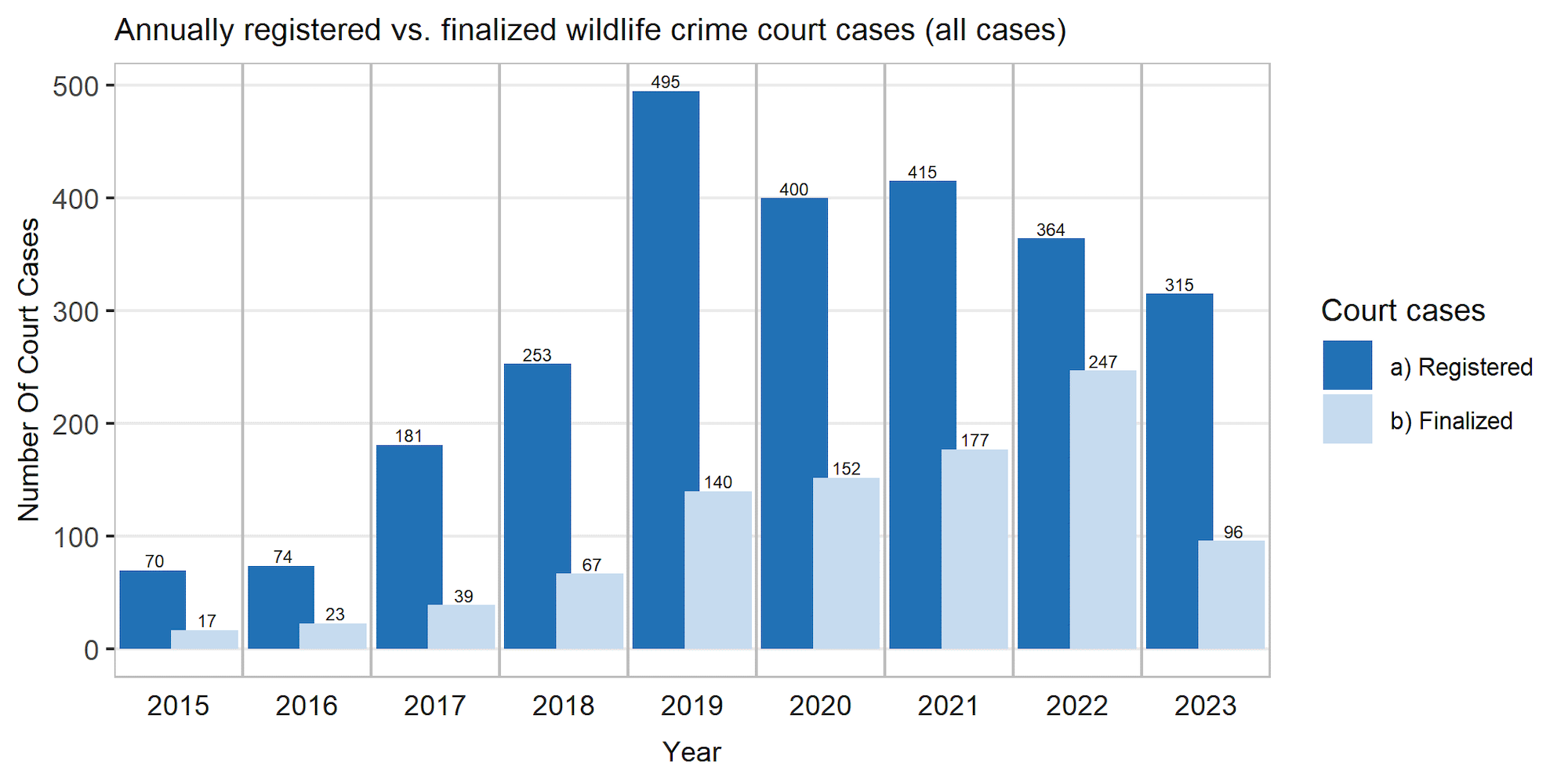

It is thus unsurprising that, in line with regional and global trends, wildlife crime has become one of the most prevalent criminal activities in Namibia. Between the start of 2015 and the end of 2023, a total of 2,567 cases related to wildlife were registered, and 5,502 suspects were arrested. The statistics are in part the result of a sudden, massive increase in wildlife crime, and in part due to increased law-enforcement. But there are other circumstances at play. These include public awareness and attitudes, increasing needs and changing lifestyle aspirations, availability of resources and evolving illicit markets.

What the statistics do not adequately portray, and what public condemnation of wildlife crime tends to ignore, is that the more than five thousand arrested suspects are people with emotions, families, social circumstances and financial needs. Some are proven repeat offenders, hardened career criminals

. Others are opportunists, trying to get away with a fast one

. Some are ignorant of wildlife laws. Many are acting in desperation, attempting to escape poverty and hunger.

Understanding what drives people to wildlife crime is an important step towards finding lasting solutions that do not rely solely on anti-poaching patrols, fines and jail sentences. A more holistic approach that is more solution-oriented rather than problem-oriented will reduce Namibia's human and economic costs of wildlife crime while including more rural Namibians in the wildlife economy.

Drivers of wildlife crime: Resource inequalities and other factors

Vast disparities exist between the rich and the poor in Namibia, which are regularly exacerbated by drought. A recent report projected that an estimated 1.4 million people in Namibia would face high levels of acute food insecurity by July to September 2024. Massive disparities exist regarding people's access to natural resources, particularly wildlife.

Private landowners can reap substantial benefits from wildlife through tourism, hunting, meat harvesting or live game sales. Some staff on commercial farms benefit substantially from wildlife, many do not.

The opportunities of those who live on communal land are much more limited. Communal conservancies enable access to wildlife, but only for the community. Individuals may see returns through employment, occasional meat distribution, cash pay-outs or community development projects. These are important benefits which have done much to empower communities and facilitate a balanced coexistence with wildlife. But they stand in sharp contrast to the profits that private-sector operators generate, even on communal land. Communal resources are also increasingly appropriated and fenced off by non-residents, further increasing rural poverty.

Human–wildlife conflict is yet another reason for wildlife crime. Healthy wildlife populations inevitably cause some conflicts, particularly in areas where wildlife coexists with farming. Wildlife legislation allows for the protection of human life and property against wildlife (based on stringent reporting requirements), but preventative or retaliatory killing of wild animals can be problematic. While freehold farmers have the necessary resources to effectively deal with problematic wildlife, communal farmers seldom do.

Many other wildlife laws make the outcome of one activity illegal, but legal for another: Collecting and selling pangolins is illegal – electric fences that kill numerous pangolins are not (because they are supposed to protect small stock from predators). Felling a rosewood to sell the timber without a permit is illegal – clearing entire stands to make way for agriculture is not.

These circumstances, coupled with the extreme poverty that is widespread across rural Namibia, create the conditions for wildlife crime to increase. Rural Namibians who live in poverty have few or no opportunities to benefit from wildlife legally. When they have suffered the loss of relatives, livestock, or crops to wild animals they will be sorely tempted to operate outside the law. Besides these internal local factors, international markets for traditional medicine, ornamental plants and exotic pets put a price tag on high-value species that lure people to poach in the hope of a better life.

A closer look at rhino, elephant and pangolin poaching

Rhino horn, elephant ivory and pangolin scales are high-value products that demand high prices on international markets, which make them a target for international criminal syndicates. While local poachers receive much less money for these products than the middlemen sell them for, the money offered is often more than rural people earn in many months.

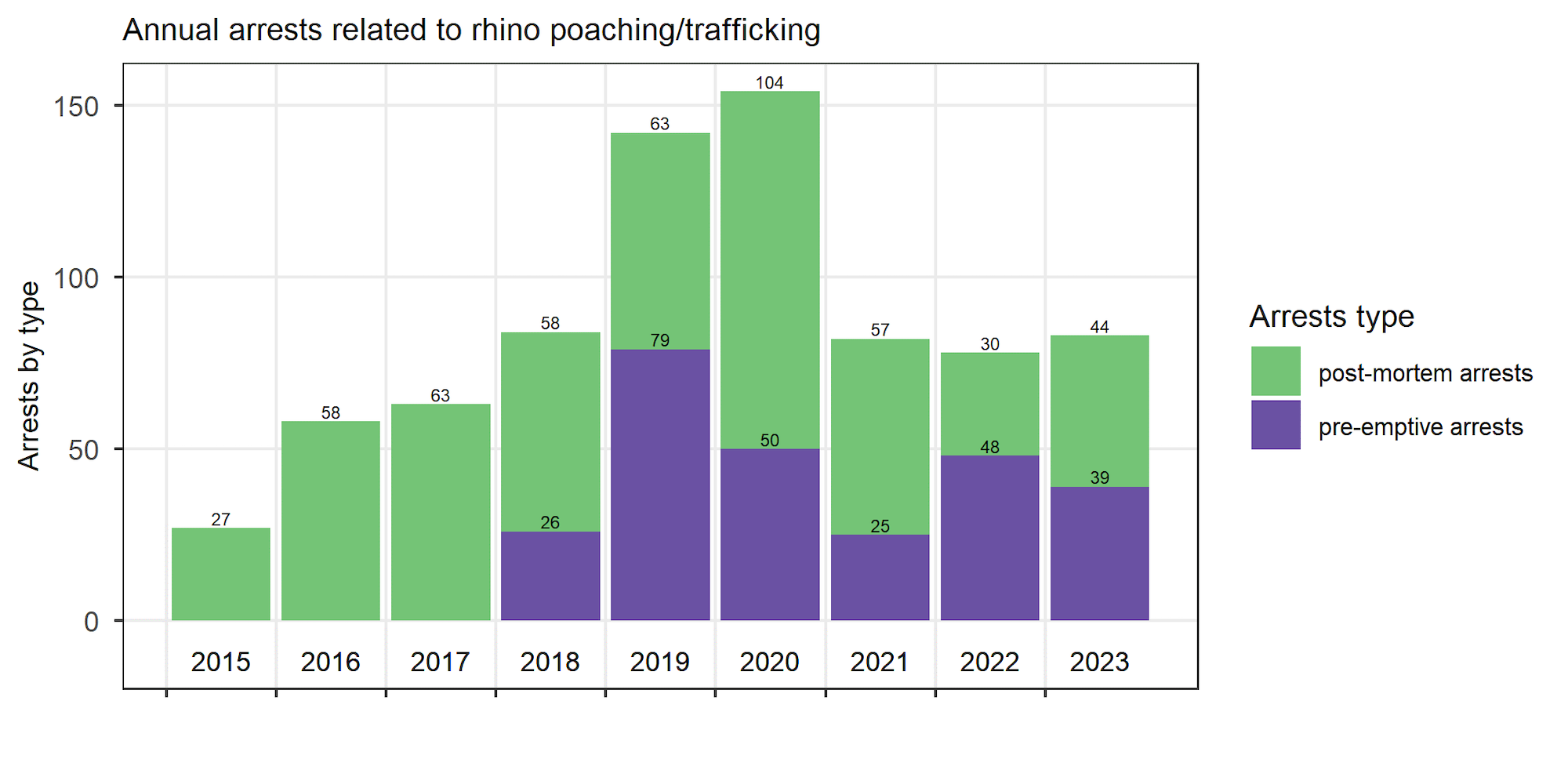

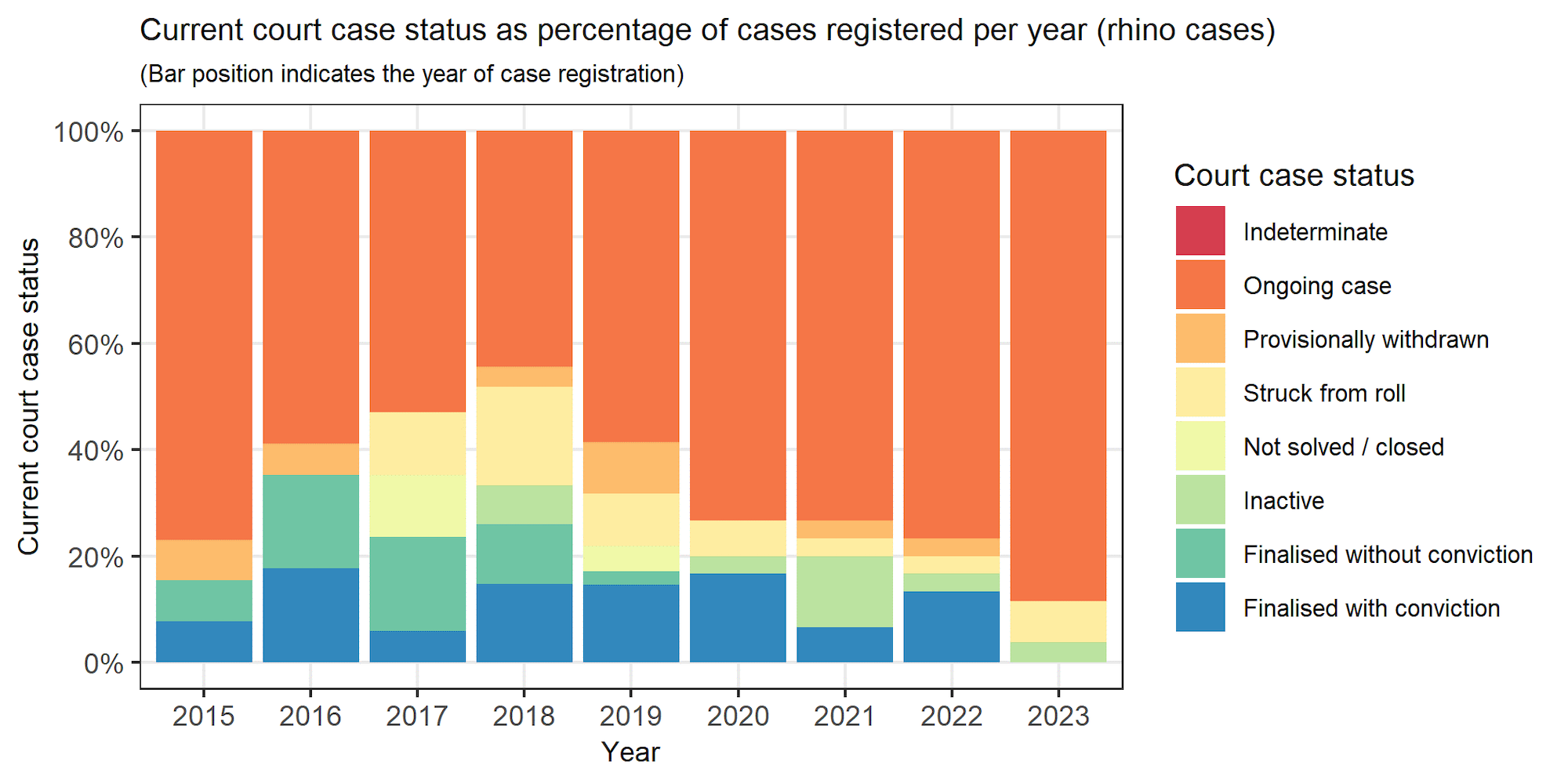

In recent years, Namibia has done very well with law-enforcement against rhino poachers and broader trafficking syndicates. This success is borne out by numerous arrests, including pre-emptive interventions that apprehend poachers while at the same time saving targeted rhinos. Prosecution of perpetrators of rhino crimes has, however, been much less effective (see graphs below). Several initiatives have been launched to address the underlying issues and improve the prosecution rate, including the establishment of a permanent Environmental Crimes Court at Otjiwarongo in August 2024.

Beyond improving law enforcement, rhino conservation alongside communal conservancies in the Erongo and Kunene regions offers a promising approach to reducing rhino poaching. Extensive community outreach campaigns combined with active patrols by community rhino rangers, supported by national security forces has significantly reduced poaching in this area.

Generating benefits from rhinos for the wider community is another key element to reducing rhino poaching. Rhino tracking is a high-value tourism product that already contributes to communal conservancies and should also be established in national parks and game reserves such as Etosha, Waterberg, Mangetti and Hardap to benefit people living around these parks. An added benefit of rhino tracking is increased monitoring of rhinos to detect poaching activities. Namibia should urgently explore this option to broaden tourism experiences, while enhancing wildlife values and strengthening wildlife protection.

Ivory prices have dropped over the past decade. Ivory is not nearly as valuable as rhino horn at present, yet elephant poaching remains a massive threat across Africa. While Namibia experienced negligible elephant poaching during the first decade after independence, over one hundred elephants were recorded as poached in 2016, motivating decisive government action. Since 2019, fewer than 15 elephants have been recorded as poached each year. Current losses no longer have an impact on the national population. The ongoing deployment of national security forces in an anti-poaching role to all key elephant ranges since 2016 is considered to be one of the main factors in this turn around.

Despite the significant drop in poaching losses, arrests related to ivory trafficking remain high in northeastern Namibia. The Zambezi Region is being used as a springboard for poaching incursions into Botswana and as a transit route for trafficked ivory. This was confirmed by collaborative transboundary investigations into seizures of large ivory shipments during 2023. Such transboundary law enforcement, combined with broader international collaboration, is vital to counter elephant poaching and ivory trafficking.

Although pangolins are considered the most-trafficked wild animals in the world, trafficking in Namibia currently does not appear to be extensively linked into global supply chains. Data related to international pangolin seizures indicates that most African pangolins being trafficked to Asia are white-bellied pangolins that originate from central and western Africa. The vast majority of pangolin poachers and traffickers arrested in Namibia are apprehended when the culprits seek to randomly sell pangolin products. No evidence of links to regional trafficking syndicates has been found, and pangolins of Namibian origin have not been confirmed as part of international customs seizures.

The motivation to pick up and try to sell pangolins appears to be opportunistic, driven by misperceptions of earning easy money. Consequently, awareness among rural communities needs to be created urgently to reduce trafficking. A significant dip in arrests involving pangolins occurred during 2022, linked to stern sentences that acted as a deterrent. Continually emphasising that potential rewards are low and risk of incarceration is high, while also building pride in pangolin protection, is likely to be an effective strategy.

Exploring the drivers of other poaching activities

Meat poaching is one of the most complex challenges in the Namibian wildlife-crime sphere, generally accounting for between a third and half of all registered cases. Yet it is important to explore and address the drivers of meat poaching. Wildlife is a traditional source of protein for most rural Namibians. During the colonial and apartheid eras non-whites were alienated from this tradition. The strict separation of freehold and communal land is another legacy of colonialism. Granting rights to wildlife after independence has done much to enhance community access to natural resources, but clear disparities persist.

Seen in this context, subsistence poaching for food requires nuanced approaches that seek to address poverty and equitable resource access, as well as enforcing laws. On the other hand, organised commercial poaching to supply meat to urban markets needs strict law enforcement, as it is driven by greed. Opportunistic transgressions, which people try to get away with on the spur of the moment

, may be best countered by actively publicising that the risks are much greater than the short-lived rewards.

Some illegal meat or trophy hunts still occur on freehold farmlands despite existing regulations that allow these hunts. Most of these involve opportunistic avoidance of permit or reporting requirements, but some are more problematic. There is still an entrenched attitude among many freehold farmers and hunting operators that they are free to use their land and the wildlife that they own as they see fit. Also, there is still a global demand to obtain wildlife trophies by any means

, with extreme prices paid for rare trophies. This combination has led to illegal and damaging activities which are being dealt with through active law enforcement to protect the legal wildlife sector and Namibia's conservation integrity.

Nuanced law enforcement and empathetic sentencing

Wildlife crime has escalated to the extent that clashes between armed poachers and anti-poaching patrols are resulting in injuries, and occasionally death. The escalating arms race

between crime and counter-crime makes such incidents inevitable, but shooting poachers for killing animals, even in clear self-defence, remains problematic. The effects of the increasing militarisation of conservation

have been the focus of much debate and research. An uncompromising approach to law enforcement can quickly create social issues, and nuanced handling of the great range of transgressions against wildlife is important.

Courts are faced with increasingly difficult decisions when seeking balanced sentences in wildlife cases. The seriousness of the crimes, the circumstances of the accused and the interests of the public often stand in an awkward relation to each other. Sentences often vary greatly, even for cases with similar circumstances, as courts struggle to find an appropriate balance. This can only be addressed through clear sentencing guidelines and ongoing awareness creation among law enforcement, prosecution and the judiciary regarding the complex dynamics and impacts of wildlife crime.

Most wildlife crime dynamics revolve around people's attitudes to wildlife, interpretations of legality and rights and perceptions of ethics. What some use as a potent ingredient of traditional medicine, others perceive as the murder of innocent animals. What some treasure as a beautiful ornamental plant in their home, others perceive as the eradication of rare endemic flora from its natural habitat. What some condemn as despicable meat poaching, others experience as alleviation of hunger.

Namibia has proven that the sustainable use of natural resources enhances the value of those resources, and through this facilitates their conservation. The heightened value of wildlife through sustainable use has been an important enabler for rebuilding some wildlife populations (the white rhino is an excellent example). This premise begs initiatives to legalise sectors that have high market demand, such as a legal trade in ivory (from natural mortalities) and rhino horn (from dehorning operations), or controlled supply for the ornamental plant trade (via registered nurseries). Such notions continue to be hampered by questions regarding effective control mechanisms to ensure legitimacy and sustainability, as well as uninformed international rejection – while species are being decimated at a rate that appears to make legalisation of their use inconceivable.

The notion of completely eradicating wildlife crime, often touted as a political battle cry, is utopian. When wildlife exists at the numbers and with the values it does in Namibia, some will attempt illicit profits. Wildlife crime in Namibia can be reduced to levels that do not cause significant harm to society, the economy or the resources being targeted. But that is only possible through holistic approaches that consider the needs of people alongside wildlife conservation.

Helge Denker is a Namibian conservationist, writer and artist. For the past seven years, he has been actively involved in interpreting wildlife-crime data and formulating internal and public information materials in collaboration with the Blue Rhino Task Team and the Rooikat Trust.

The graphs and photographs in this article are from the Government of the Republic of Namibia. 2024. Wildlife Protection and Law Enforcement in Namibia: National Report for the Year 2023. The full report can be downloaded from the special publications section of our website.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.