Can we take the Angolan giraffe back to Angola?

27th July 2021

The Angolan giraffe is a subspecies of the Southern giraffe, one of the four recently identified giraffe species in Africa (giraffe were previously considered to be one species). As the name suggests, the Angolan giraffe historically occurred across south-central Angola, including the southern Huila provinces where Iona National Park is located, and areas west of the Cuito and Cuando-Cubango rivers. Sadly, this population of giraffe was one of the casualties of the 40-year Angolan armed conflict. Now that Angola is enjoying political peace, it is time to bring the peaceful giraffe back to its former range.

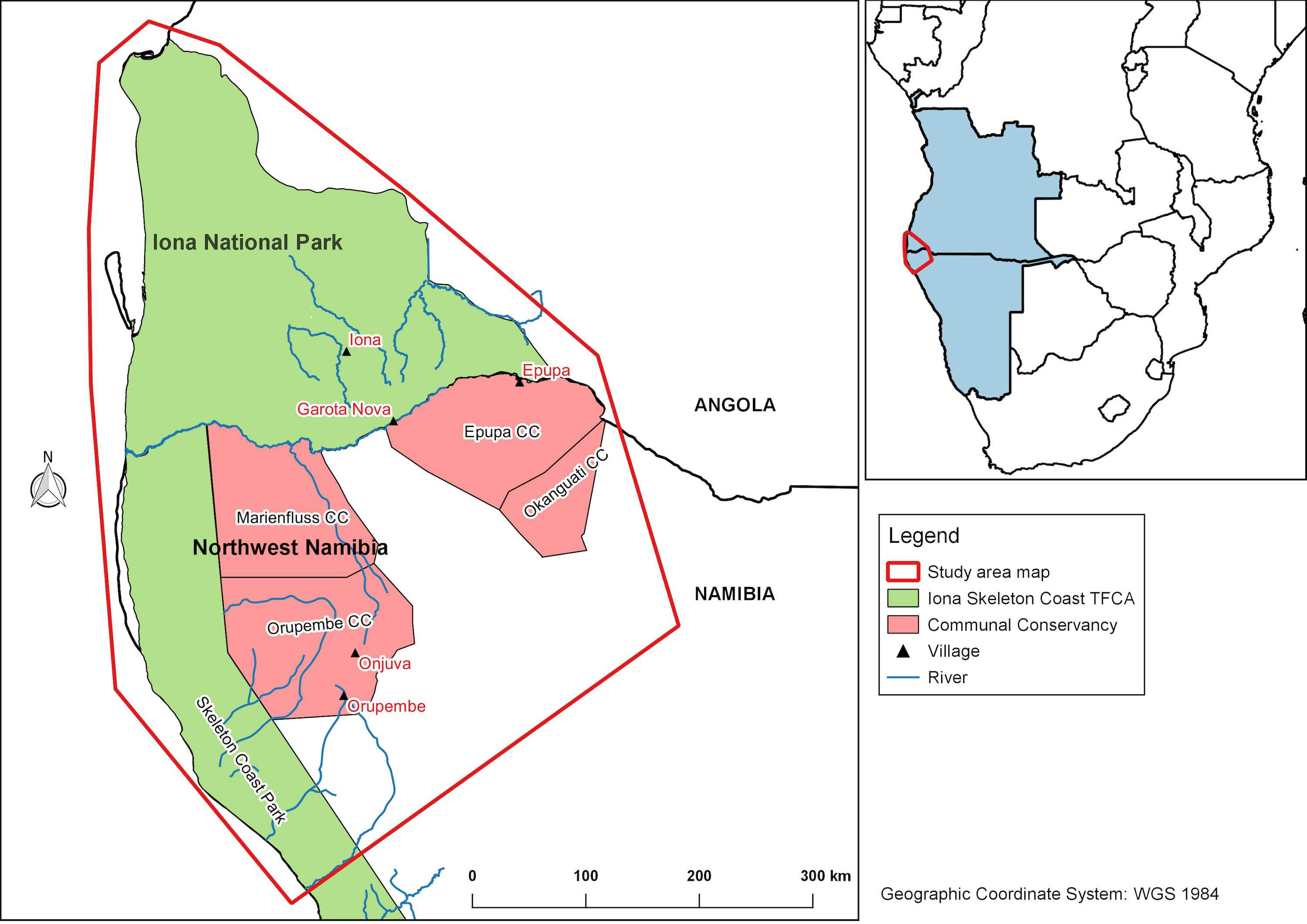

The protracted armed conflict from the 1960s until the early 2000s caused tremendous suffering for the people of Angola and its wildlife was all but eradicated, including the giraffe. During this perilous time, national parks were abandoned, affording no protection for wildlife. When the civil war finally ended in 2002, the Angolan government renewed its commitment to conservation. As its southern neighbour, Namibia stands ready to help restore Angola’s beautiful wild landscapes to their former glory. One of the results of this joint commitment is the new Iona-Skeleton Coast Transfrontier Conservation Area (TFCA). To support the establishment of the new TFCA, the European Union has funded the SCIONA project, which will provide critical scientific conservation management and monitoring information for the TFCA.

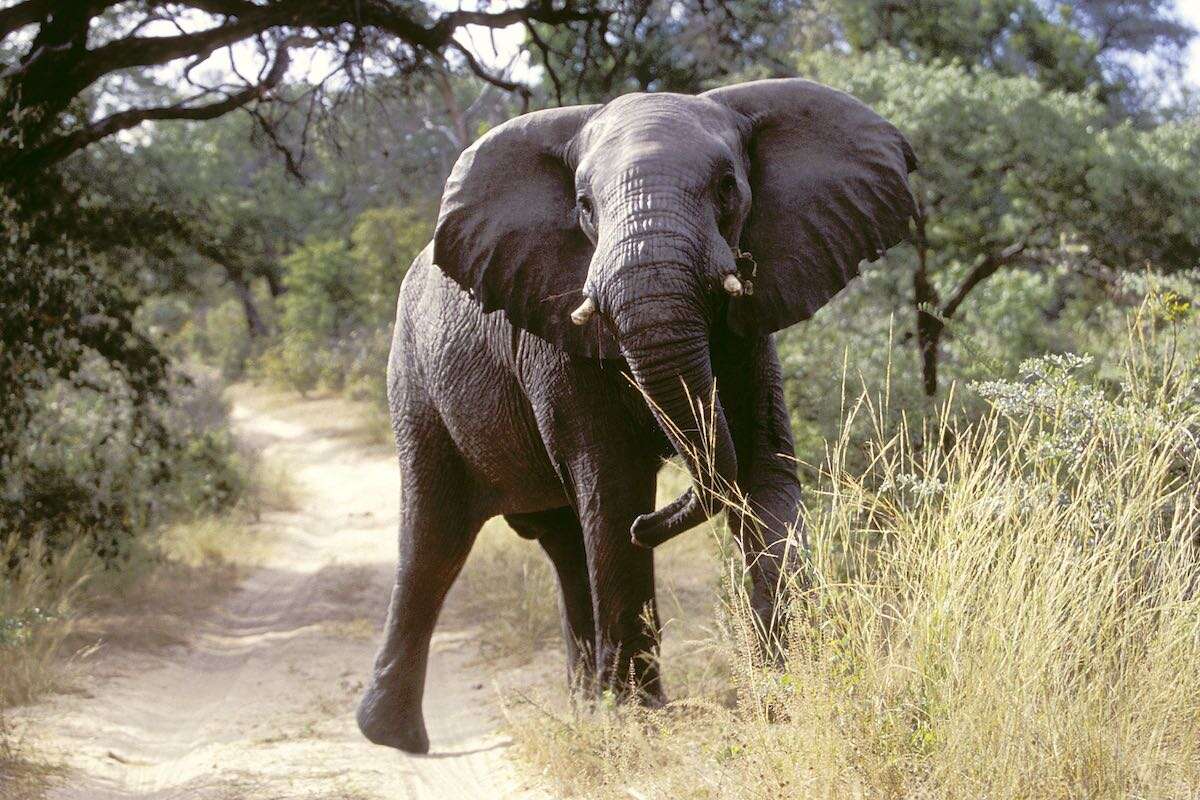

The Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) estimates that there are more than 14,500 giraffe occurring in Namibian National Parks, private land and communal land; about 425 of these giraffe live in northwest Namibia (known as the Kaokoveld) which provides similar habitat to Iona NP. Consequently, Namibia provides an ideal source population for potential reintroductions to Angola. Giraffe are thriving in the Namibian part of the TFCA and have become an iconic part of the Kaokoveld and Skeleton Coast landscape, with local communities living alongside them. Reintroducing giraffe to Angola from the healthy Namibian population would be a great way to demonstrate true transboundary conservation.

Considering all that Angola has gone through, however, there are some important questions that need to be answered first. Would the introduced giraffe survive? Are ecological conditions still suitable? Would the increased human settlement within and on the periphery of Iona NP threaten their chances of survival? As part of the SCIONA project and in collaboration with GCF, I sought to answer these questions by undertaking a feasibility assessment for reintroducing the Angolan giraffe to Iona NP.

The answer to whether or not giraffe would survive in Iona NP might seem obvious, considering that the area is part of their former natural range. However, research on reintroductions suggests that historical occurrence, or a superficial look at the reintroduction site, is not enough to ensure success. Feasibility studies provide essential information on the current state of the habitat and other social, economic and ecological factors. A feasibility study is especially important when a long time has elapsed since the local extinction of the species, as there is a chance that the habitat is no longer suitable or that the people now living in Iona NP would not protect the newly introduced animals.

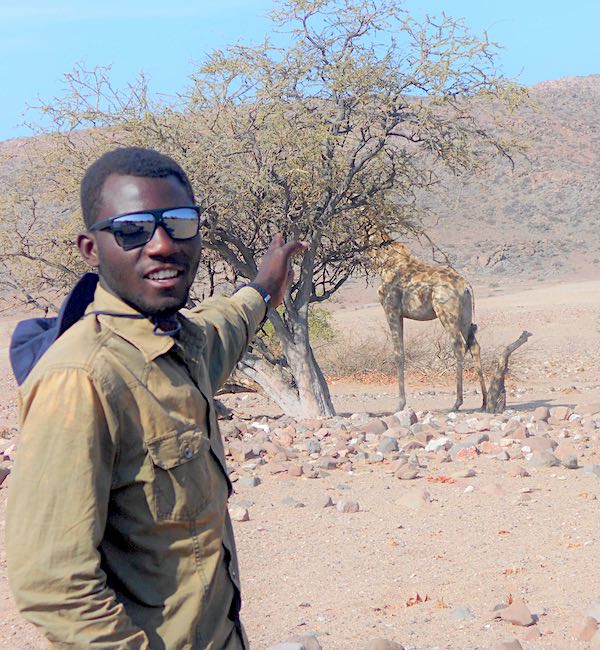

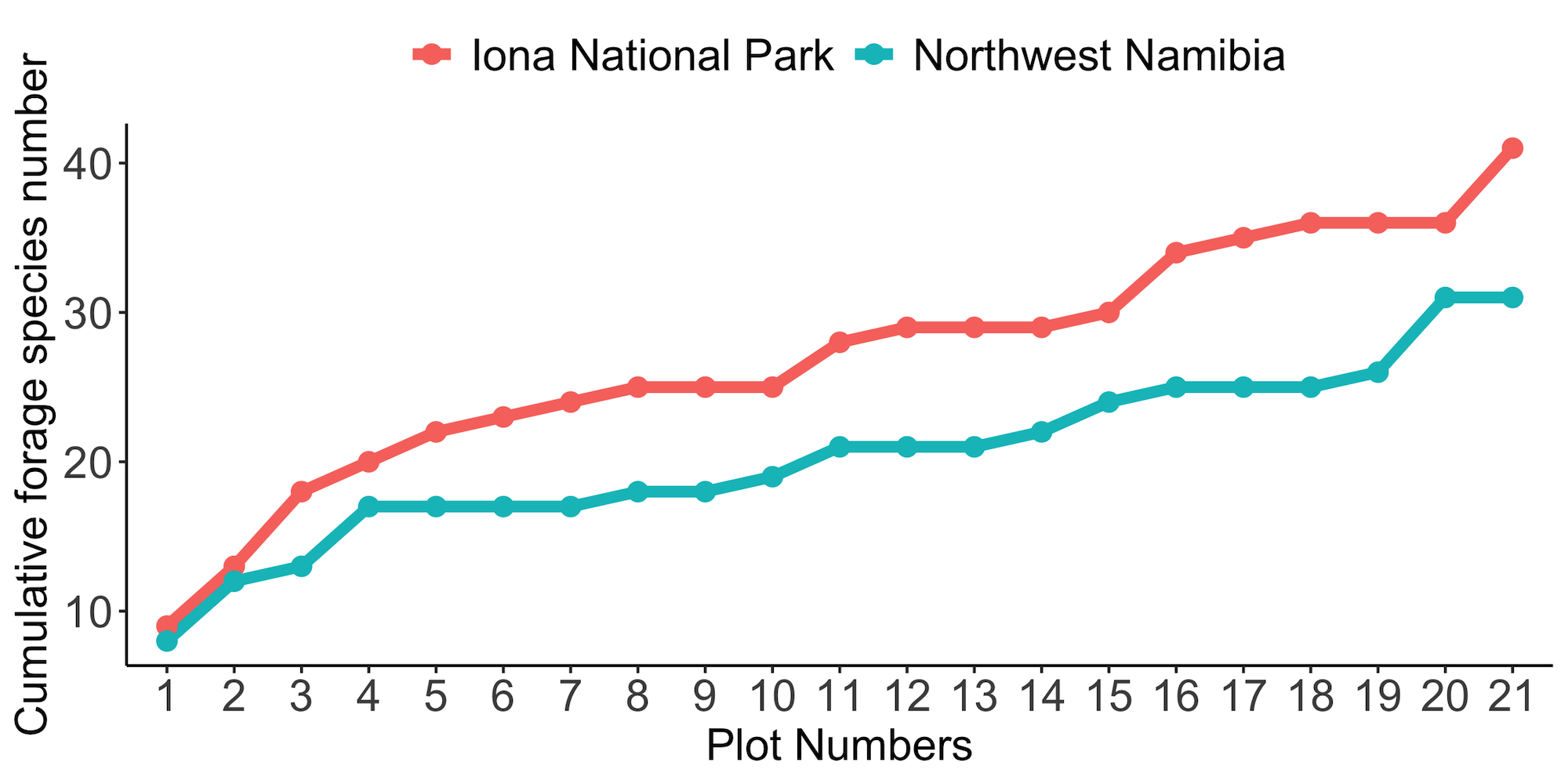

To assess if Iona NP still offers viable giraffe habitat and whether it can support the species in the long term, I used northwest Namibia (current giraffe habitat) as a model to identify the extent of similar habitats in Iona NP. In particular, I assessed giraffe spatial ecology in northwest Namibia to predict how reintroduced giraffe would use the habitat available in Iona NP. For this purpose, I joined the GCF team to fit GPS-satellite units to seven giraffe in northwest Namibia in July 2019. Besides seeing how giraffe use the habitat over time, I identified plants giraffe prefer foraging on in Namibia. I then conducted vegetation surveys in parts of Iona NP to evaluate the abundance and distribution the giraffe’s preferred plant species.

Finally, I conducted a questionnaire survey with the community living in Iona NP to assess their willingness to co-exist with giraffe, their attitudes towards a possible reintroduction attempt and the risk of future giraffe poaching. This study therefore provides direct conservation management recommendations for giraffe reintroductions in Angola.

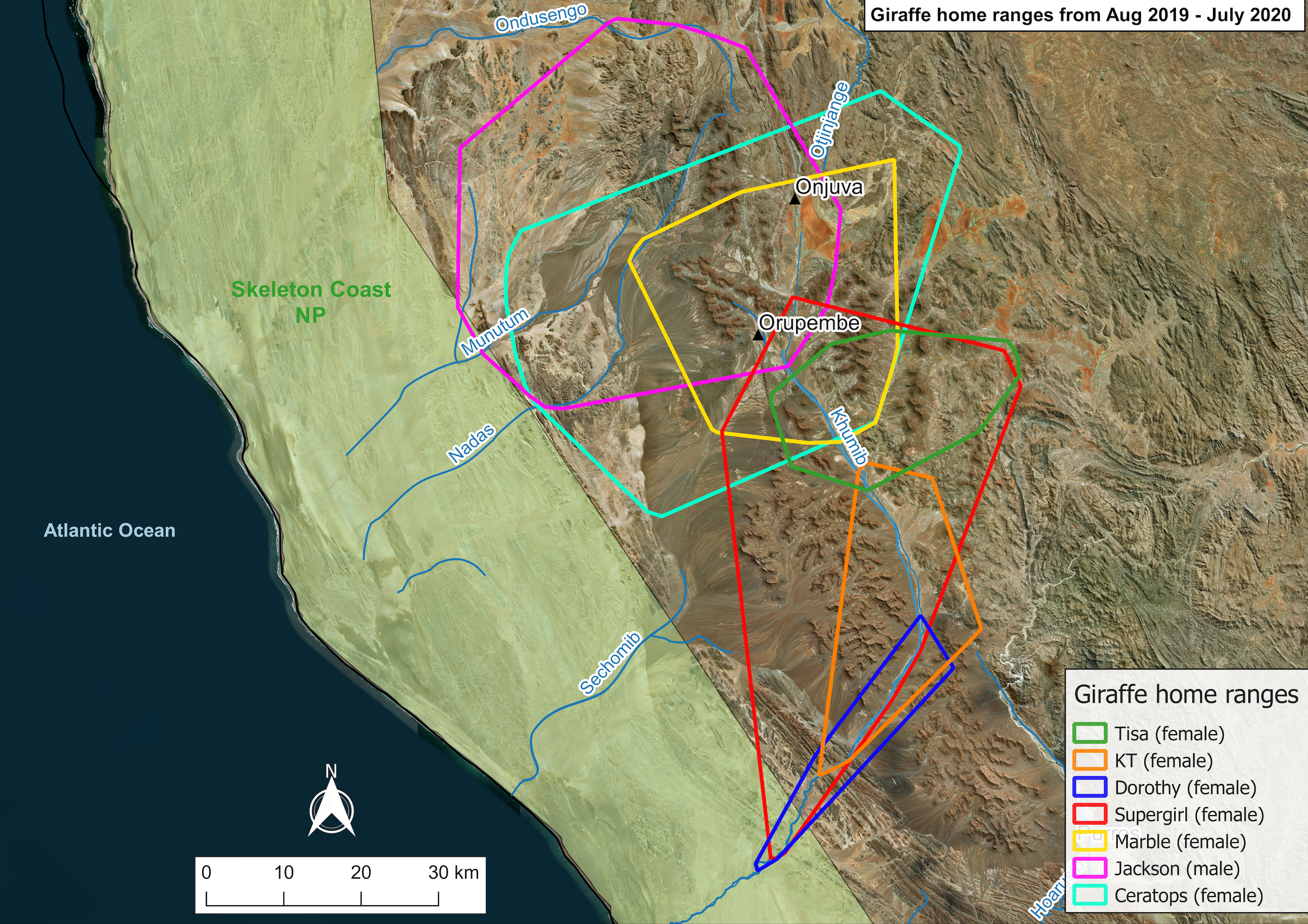

The Kaokoveld giraffe have some of the largest home ranges on the African continent. The main reason for this is the sparse vegetation and resulting low forage density, meaning that giraffe living here must roam widely to fulfil their nutrient requirements. Male giraffe also have to search larger areas for females – the one male in our study (Jackson) walked up to 9.7 km per day and covered 256.5 km per month. One of the females (Ceratops) travelled even further than Jackson, covering 273.1 km per month and 8.9 km per day. Her movement patterns most likely reflect avoidance of human disturbances in and around Onjuva and Orupembe villages, one of the most densely populated areas in northwest Namibia (see map below).

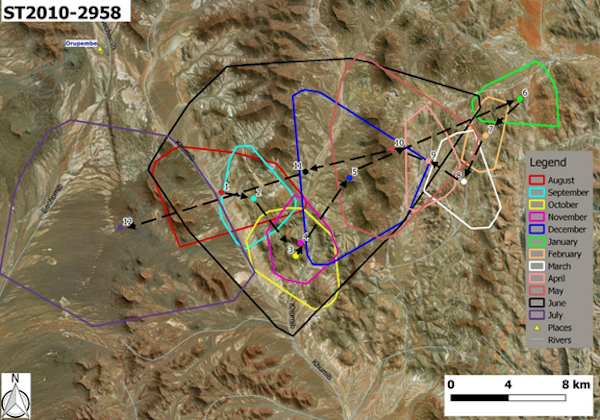

Giraffe in northwest Namibia predominantly rely on the riparian woodland in and around the dry riverbeds that cut through this mountainous landscape. I found that they occasionally wander far away from the rivers, most likely to supplement their diets by feeding on non-riparian plants. One particular female (Tisa) had a fascinating monthly movement pattern. During the hot, dry season from August to November, she ranged mostly in tributaries a short distance from the upper Khumib River on the eastern side of the study area. In the hot, wet season (November to January), she moved further east into the tributaries and their riparian zones. Yet during the cold, dry season (May to July), she suddenly headed west and landed up back to where she was first tagged in the main river to forage on mostly evergreen trees during this critical time. It appears that most of these giraffe tend to move back to the main rivers where they obtain their main sources of food mostly from evergreen trees.

The vegetation surveys were highly promising – productivity, cover and diversity of plants preferred by giraffe were higher in Iona NP than in the Namibian study area. Iona’s plains, lower mountain slopes and dry riverbeds provide even more forage for giraffe than northwest Namibia. Although Iona NP is about half the size of the study area in northwestern Namibia, it can support a higher density of giraffe. Besides giraffe, Iona NP could sustain several other species of wildlife that were eradicated during the war.

Finally, inhabitants of the park and its periphery seem highly receptive to giraffe and the tourism potential they may bring. Since giraffe do not compete with livestock for forage and do not require water (those in Namibia obtain moisture from the leaves of the plants they eat), human-wildlife conflict is unlikely. Although the people I interviewed were optimistic that the giraffe would not be poached, other species continue to be poached in the Park, mainly because there are very few anti-poaching rangers patrolling a vast area. Poaching giraffe for meat is therefore the main risk for this reintroduction effort, especially near the periphery of the park. My study therefore recommended close monitoring of reintroduced giraffe to keep this population safe, at least until numbers recover and the park’s capacity to prevent poaching increases. Monitoring efforts could also involve local people, thus giving them a stake in the giraffe’s survival.

My results demonstrated that it would be feasible to reintroduce Angolan giraffe back to their former range due to habitat suitability, abundance and diversity of preferred giraffe forage plants and the positive attitude of local inhabitants towards receiving giraffe. The poaching risk can be reduced through closely monitoring the giraffe that are released and maintaining local support for their presence. With this information, conservation planners and managers can take the next steps towards bringing the Angolan giraffe back to Angola.

This study was conducted jointly by the Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST), the Higher Institute of Education Sciences (ISCED) in Angola, and in collaboration with GCF to support giraffe conservation in southern Africa. I am grateful to the following project sponsors: Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE), Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) and the SCIONA project.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

If you enjoyed this page, then you might also like:

The NUST Biodiversity Research Centre produces quality trans-disciplinary research to support data-driven decision-making for wildlife management and conservation. We welcome school learners who are considering a career in biodiversity or conservation field to visit the centre. The post-graduate students will gladly demonstrate their work and share their experiences. Like us on Facebook to stay up to date with our research projects.

Jackson Hamutenya, supervised by Professor Morgan Hauptfleisch (NUST), Dr Vera De Cauwer (NUST) and Dr Julian Fennessy (GCF), graduated in June 2021 with a Masters degree in Natural Resources Management at the Namibian University of Science and Technology (NUST). Jackson was trained as a natural resource manager and a conservationist at NUST in the field of Natural Resources Management. His greatest happiness comes from seeing animals living free from fear and pain within a healthy environment. Jackson is currently employed by Giraffe Conservation Foundation.

Jackson Hamutenya, supervised by Professor Morgan Hauptfleisch (NUST), Dr Vera De Cauwer (NUST) and Dr Julian Fennessy (GCF), graduated in June 2021 with a Masters degree in Natural Resources Management at the Namibian University of Science and Technology (NUST). Jackson was trained as a natural resource manager and a conservationist at NUST in the field of Natural Resources Management. His greatest happiness comes from seeing animals living free from fear and pain within a healthy environment. Jackson is currently employed by Giraffe Conservation Foundation.

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.