Freehold conservancies:

A neglected part of Namibia's conservation story

27th October 2024

27th October 2024

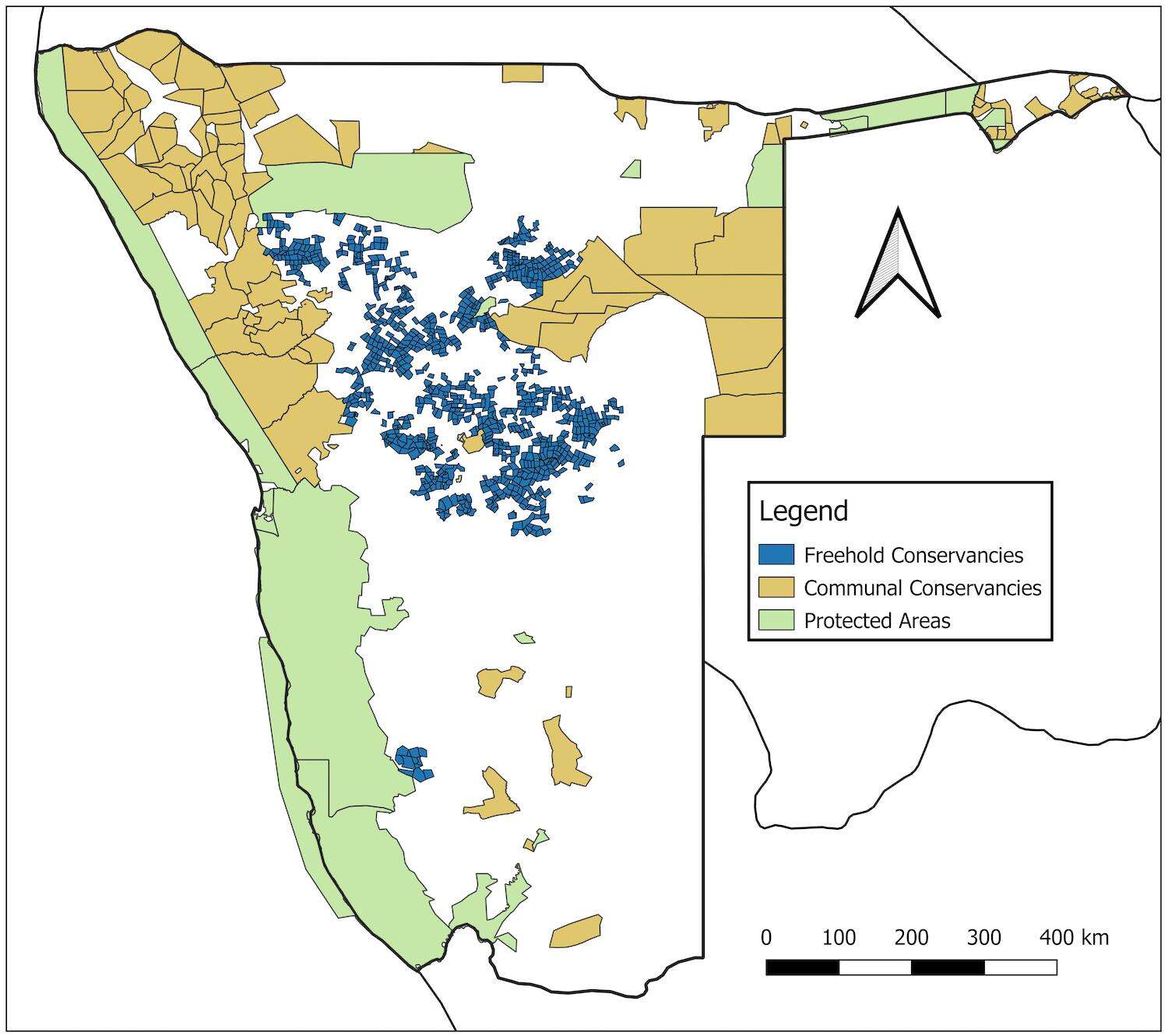

Namibia's freehold farmlands host 80% of the country's wildlife. This is the result of forward-thinking policies implemented during the 1960s and 70s that allowed for private ownership over wild animals. Freehold farmers would nonetheless be able to contribute much more to national conservation efforts and global targets if their conservancies were fully supported and incentivised by the government.

What are freehold conservancies?

While many people are aware of the history and role of communal conservancies in Namibia, fewer know about the conservancy movement on freehold farms that started with the establishment of Ngarangombe Conservancy in 1991. Prior to this, freehold farmers started conserving wildlife on their farms in response to the Nature Conservation Ordinances of 1967 and 1975 that granted landowners the right to own and use the wildlife on their land for economic purposes.

As game numbers increased because game was now valued for trophy hunting, live sales, meat and photographic tourism, increasing numbers of landowners constructed game-proof fences to keep wildlife on their land. This cut off the migration routes of large herds of plains game, which then required more intensive game ranching to maintain their population sizes in an ecologically sustainable manner.

Understanding the long-term ecological issues that the fragmentation of land would have for wildlife, some freehold farmers considered joining their farms together and managing their wildlife cooperatively. This notion was strongly supported by farsighted government officials in the early 1990s, who visited farmers associations throughout the country and enabled the establishment of the first conservancies.

Five years before legislation was passed to allow conservancies on communal lands, these first freehold conservancies were trailblazers. They defined a conservancy as A legally protected area of a group of bona fide land-occupiers practising co-operative management based on a sustainable utilisation strategy, promoting conservation of natural resources and wildlife while striving to reinstate the original biodiversity with the basic goal of sharing resources amongst all members

. This definition extended to people living on communal lands, which were yet to receive the legal right to establish their own conservancies.

Whether on freehold or communal land, conservancies are voluntary associations that are led by people living with these communities who wish to conserve and use their wildlife sustainably. Conservancies represent a mosaic of Namibia's diverse landscapes, from the arid deserts to lush river valleys, each with their unique challenges and opportunities.

Creating a unified voice: Conservancies Association of Namibia

By 1996, the number of freehold conservancies had grown substantially, creating a need for greater coordination and a unified voice to address cross-cutting challenges and cooperation with what was then the Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET). The Conservancies Association of Namibia (CANAM) was established to meet this need. Supported by MET, CANAM aimed to represent and coordinate all conservancies across Namibia, whether in communal areas or on freehold farmland.

CANAM's objectives are multifaceted. It represents conservancies, liaises with authorities, encourages landowner participation, coordinates research, protects the environment and raises awareness both locally and internationally. Beyond these goals, CANAM embodies a spirit of cooperation and a shared commitment to conservation. During its peak, up to 25 conservancies on freehold farmland were united under CANAM.

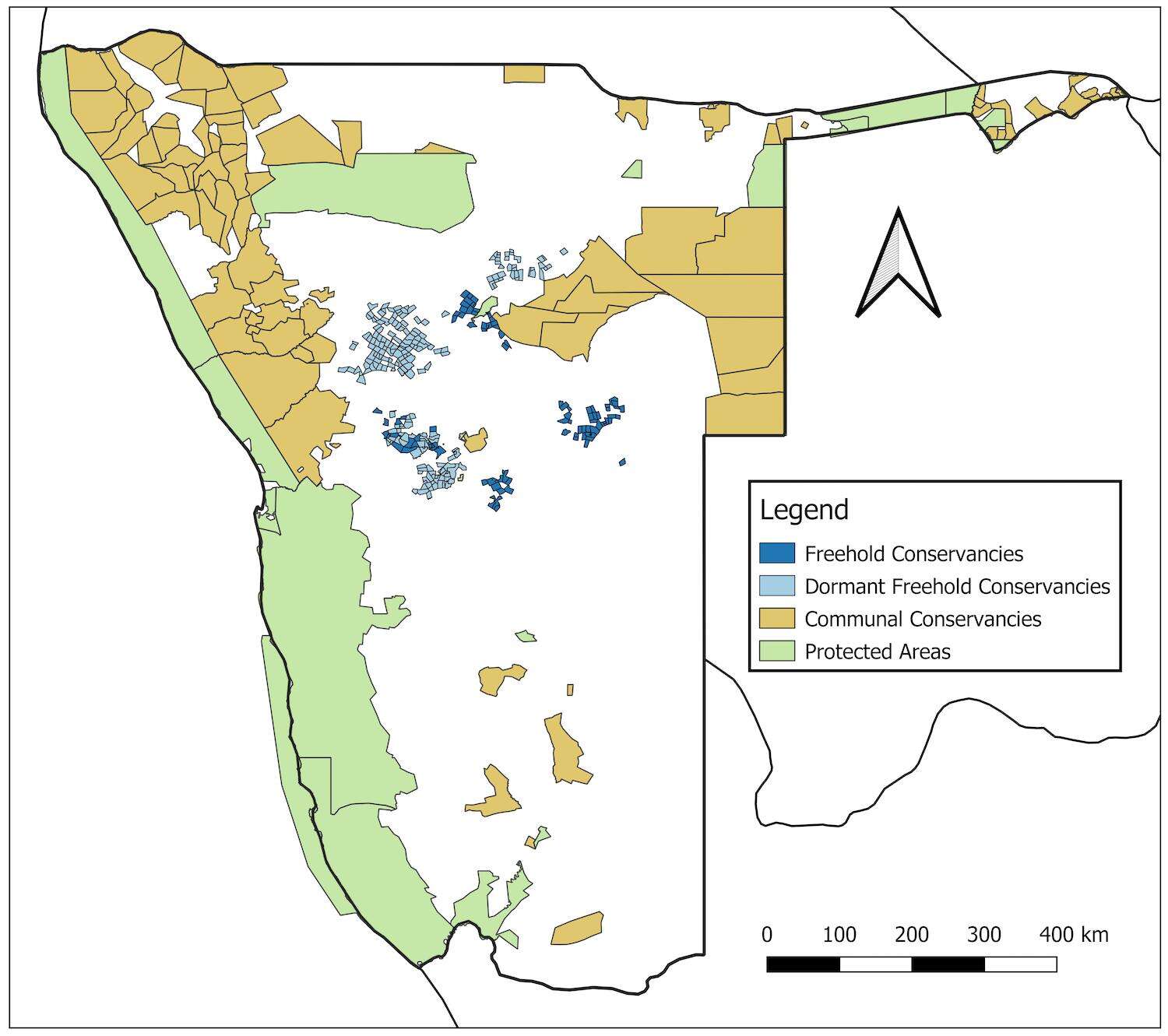

Unfortunately, because of the different legal requirements for establishing communal conservancies, they were supported and developed separately from freehold conservancies during that time. This led to limited cooperation across land use types and restricted CANAM to representing freehold conservancies only. This divide has led to declining support for freehold conservancies from government and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) over the past few decades, leading to a decline in CANAM membership and the eventual shrinkage or dissolution of many conservancies.

Call for renewed support of freehold conservancies

Freehold farmlands conserve most of the wildlife in Namibia, provide thousands of jobs and contribute to a vibrant wildlife economy. Occupying most of the central parts of the country due to historical land distribution, freehold lands could provide important links between conservancies and national parks on communal and state land. The prevalence of game fencing is a key factor limiting connectivity, which would be addressed through properly supported freehold conservancies.

Under the current Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT), freehold conservancies receive no support, in contrast to the early years. Conservancies used to enjoy greater autonomy in terms of wildlife management than individual freehold farmers, thus incentivising landowners to create conservancies. These benefits have been withdrawn, reducing the incentive for freehold farmers to participate in landscape-level conservation. The resulting decline in the number and size of freehold conservancies is detrimental both economically and ecologically, especially as Namibia faces the dual challenges of climate change and international pressure regarding the sustainable use of wildlife.

Looking beyond Namibia, freehold conservancies contribute to global conservation targets, particularly Target 3 of the Global Biodiversity Framework that aims to protect 30% of the planet's land and oceans by 2030 (known as the 30 by 30 target). Freehold conservancies already comprise vast tracts of land that support biodiversity and wildlife conservation and therefore meet the international definition of Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs). They also protect vegetation types which are not adequately protected by national parks. To make significant gains for global conservation, the Namibian government only needs to formally recognise freehold conservancies as OECMs that contribute to the global 30 by 30 target and incentivise their formation through minor policy changes. This would restore game migrations in Namibia, assist predator conservation efforts and allow for greater collaboration across land use types.

CANAM is ideally positioned to revitalise the freehold conservancy membership and create a win-win partnership between the public and the private sector. We are willing to work with MEFT to identify key policy changes that would incentivise farmers to once more establish (or revive) their conservancies and work closely with the government to achieve the joint goals of nature conservation and sustainable rural development.

CANAM continues to advocate for freehold conservancies to be rightly recognised as contributors to national and global conservation goals. The vision for the future is clear: a robust network of conservancies that support biodiversity, sustain wildlife and provide economic benefits. The story of CANAM and Namibia's freehold conservancies is one of resilience, cooperation and hope.

For articles on similar topics, please click one of the following options:

For more great articles from Conservation Namibia see below...

Conservation Namibia brought to you by:

We use cookies to monitor site usage and to help improve it. See our Privacy Policy for details. By continuing to use the site, you acknowledge acceptance of our policy.